Bargaining

Bargaining

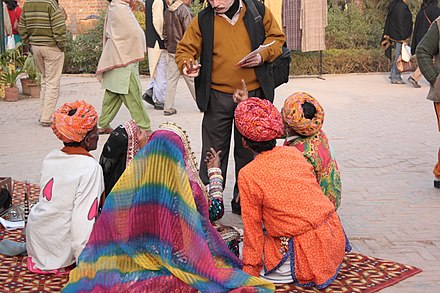

Bargaining, also called haggling, is common in many countries, such as most of Asia, Latin America and North Africa. In other places, it may generally be used only for large items with no fixed price, such as buying a house or a used car. However bargaining is possible in almost any flea market or tourist shop anywhere. In such places, if you don't bargain, you are almost certain to pay more than necessary. Vendors expect a bit of bargaining so their initial asking price is considerably higher than they hope to receive, which in turn is higher than the minimum they could accept and still make a profit.

This article is about cultures where bargaining is common. In some other places it may be possible to ask for a discount, but there the nominal price is close to what you will pay and your first suggestion should be reasonable, perhaps the price you hope to get.

By all means bargain hard and try not to get cheated, but do not expect too much. You are a visiting amateur going up against a professional on his or her home turf. Just holding your own and getting a reasonable price will be an accomplishment; do not expect to achieve some miraculously low price. Against a pro boxer, almost anyone would be justifiably proud just to leave the ring on their feet; hoping to win the bout would be foolish and hoping to score a knockout utterly ludicrous.

Don't get upset if you pay somewhat more than a local would; that is quite normal in many areas. Even getting "cheated" in a local bazaar, perhaps paying $25 for something a local could buy for $10, is often better than buying it in some overpriced airport shop. It will usually be cheaper if you have even basic bargaining skill, and buying in the bazaar puts money into the local economy, rather than giving it to some large company or, in some places, helping crooked officials line their pockets.

If possible, try to buy in areas where there are many vendors and competition may bring prices down. In an example from China, one traveller reports finding some lovely silk shawls in the only store at a well-known scenic site, beating the price down down from ¥250 to ¥100, and thinking he had done reasonably well. A few days later he found the same shawls in a nearby multi-vendor commercial area with an asking price of ¥80 and bought a half dozen at ¥55 each. He felt a bit foolish but did not feel he had been robbed since back home those shawls would likely have cost at least the equivalent of ¥350; even a naive tourist paying ¥200 is not being robbed.

Consider your priorities. If you are bargaining over some silk item that would cost $200 back home, it may not be worth worrying about whether you pay $20 or $25 in Thailand. If you make good money and are spending a substantial chunk of it on a trip, then it makes no sense to waste a half an hour to save $5; your time is worth more than that and you have plenty of better things to do with it during a trip.

Also consider the vendor's situation. Sometimes the amounts you are arguing over are just a pittance to a traveller from a relatively rich country, but are quite important to someone in a poorer country who needs to make a living off the tourist trade. An amount that is large to you may be huge to the vendor. In some cases, for example, a big sale might mean the difference between all the vendor's children going to school this year or just the boys.

See the Shopping article for some alternatives that may let you avoid bargaining.

Basic tactics

The key to making a good deal is knowing the right price. If you know the right price you can just state your price, start leaving the store and your offer will usually be accepted. Try to have a rough understanding of the item's value before you start haggling.

- Hotel or airport gift shops generally have (high) fixed prices that will at least give you an upper boundary.

- Government-run craft shops exist in many countries to market local products. These also often have fixed prices, but more reasonable ones that give a more useful boundary. They also generally have good quality so for many travellers buying in them is a sensible alternative to haggling elsewhere.

- Shop around, especially for items available from multiple vendors in tourist areas.

- Ask other travellers what they paid for similar goods and try to make a better deal.

- If you buy several similar items, try to make a better deal each time.

- If you can, ask a trusted local what price range is appropriate.

- If possible, try to see what locals pay and refuse to pay more. You can either watch, or ask someone after they have purchased. Try not to be obvious; in some parts of the world locals will defer purchases so that the vendor can extract additional profits from you as an outsider.

Do not let unknown locals "help", with either bargaining or finding what you need; you will very likely end up paying an extra commission. In many places, this includes tourist guides and taxi or rickshaw drivers; some shops pay them substantial commissions to bring in customers, those shops are usually overpriced, and some guides or drivers will take you only to such shops. To get good prices, you need to go shopping without a guide and preferably on foot.

It may help if you can adjust the vendor's expectations. If he thinks you are rich, the price may go up. To get a better price, tell him you are a backpacker on a tiny budget, a student, an English teacher on a low local salary, or whatever. You cannot really afford what he is selling, but you like it a lot; can he do something to make it possible? When doing this, try not to look rich; a Rolex on your wrist and $2000 worth of camera around your neck will definitely not help.

Be strong. Don't let them get to you, no matter how hard they push. You might be offered tea, coffee, snacks, etc. You can accept them and it does not mean you have to buy anything, although you may be 'guilt-tripped' later. You have only one obligation; to buy once a price is agreed. Until you make an offer that the vendor accepts or vice versa, you have absolutely no obligations beyond common courtesy.

During the actual bargaining:

- Be courteous and friendly (but firm) in your negotiations. If the vendor takes a personal liking to you, you will almost always get a better deal.

- Just as vendors often start with absurdly high prices, in most cases you should start with a low initial offer. For example, if you think an item is worth around $100 and he or she asks $500, offer $20. This gives you some negotiating room. More generally, your first offer should always be well below what you hope to pay. Don't go overboard though: offering a dollar for something worth $500 wastes everyone's time and indicates to the vendor that further talk with you is not likely to be worthwhile.

- Try to move in small increments. For example, if you think $500 might be a fair price, the vendor asks $1000, you offer $200 and he counters at $800, resist the temptation to move quickly toward a deal by offering $400. Offer $250 which indicates you are willing to negotiate but puts pressure on him to come down more if he wants a deal.

- Later in the process, use even smaller increments; if you think $500 might be fair, your last offer was $400 and he says $600, don't jump to $500 or even $450. Either tell him $400 is the best you can do or offer something like $410 or $420.

- A common tactic is to bid the vendor farewell and start walking off. You will usually get at least two offers as you walk away, each lower than the previous. Alternatively, the vendor may ask "How much do you want this?" (or words to that effect), which acknowledges the fact that they realise a potential sale is walking out of the door. In some cultures it is also common for the salesman to walk off if the price is too low. This occurs the closer you get to the profit threshold but stay firm, the salesman will return in minutes to try more bargaining (Ex: Ghana beach salesman).

- You really should walk away from bad deals, especially for tourist items where there are many vendors in an area. If someone asks $150 for something worth about $10, don't even try to bargain; just look for another vendor.

Some guides and articles suggest that, when you have no idea what a fair price might be, you should offer a fixed percentage (a half, a third, a quarter...) of the shopkeeper's first price. Alas, in general this doesn't work: many shopkeepers are perfectly aware of this tactic and will thus first offer an absolutely ridiculous price that can be tens or hundreds of times more than the real value, which they will then be more than willing to negotiate down to "half".

If you feel that you must have a general rule to go by in those situations, remember that in tourist areas it is quite common for a moderately skilled bargainer to pay below a quarter of the initial asking price, and an eighth is not unheard of. You should start below what you hope to pay, so your first offer should be around a tenth of the asking price. If you really want to just get the bargaining over with, and do not mind paying over the odds to accomplish that, you could go as high as a fifth.

Knowledge is power

The more you know about the merchandise, the better. For example, you can buy cheap pottery in any flea market on Earth with no expertise at all, but if you are planning a trip, want to spend a significant amount to bring home some fine porcelain, and are not an expert, then you should read a few books on the subject and visit museums (either near home or at the destination) before shopping. The Wikipedia articles on the topic may be a fine starting point. See our article on carpets if you want those.

The more you know about the merchandise, the better. For example, you can buy cheap pottery in any flea market on Earth with no expertise at all, but if you are planning a trip, want to spend a significant amount to bring home some fine porcelain, and are not an expert, then you should read a few books on the subject and visit museums (either near home or at the destination) before shopping. The Wikipedia articles on the topic may be a fine starting point. See our article on carpets if you want those.

- Provided you understand the merchandise, it is often worth paying for quality. For example, a $200 pair of boots — skillfully made of fine leather and likely to last for years — may be a much better buy than a $20 pair that may fall apart in weeks.

- If you do not understand the merchandise well, avoid expensive items. In the example just given, the risk is that you may pay $200 for boots that would not be a good buy at $20.

- The more expensive the item, the more important this is; there are forgeries of all sorts of expensive items, from Stradivarius violins to Nikon lenses, and modern replicas of many expensive antiques. Replicas can be a good buy at the right price, but not at the cost of an original.

The same advice holds for items that come in a range of types or grades at widely varying prices. A fine carpet or a topnotch wine may be a good buy even at a high price, and a cheap one worthwhile even if its quality is relatively low. However, if you don't understand the differences, then you should only consider the cheaper ones.

The more you know about the country you are in, the better. You may not get the price a local would pay, but you are almost certain both to enjoy your shopping more that an ignorant foreigner would and to get a better price. Specifically: Count 'em up

0 to 9 in various scripts: ; Arabic : <big></big> ; Devanagari : <big></big> ; Thai: <big></big> ; Chinese and Japanese :

- If you are in a country that does not use Western numerals, then learn the local numbers. It will save you a lot of time and money when you are bargaining about a hotel room and there is a price list right in front of you. You should still bargain, but it gives you a starting point. Sometimes having a piece of paper and pen or a calculator to display the price you're offering can be helpful.

- Even better, learn some of the local language. Even just being able to count in the local language can win you some respect and therefore a better price. If you can, stick to the local language even if the seller uses English or your own language. Some vendors outright say that they offer better deals if you speak the local language and speaking enough of the local language enables you to understand what the vendor says to her colleagues or other customers.

- Investigate local superstitions (see the Buy sections of country articles for the ones we know of) and use them if possible. In some countries, the first deal of the day or of the new year is thought to indicate how the rest of the day or year will go for the merchant. If a vendor believes that, then he or she really does not want to lose that sale, so being there at the right time can be to your advantage.

More advanced methods

Some bargaining techniques take more effort or planning, more nerve, more practice, or a bit of acting skill. These may even be worth practicing beforehand.

- If there are two or more of you, you can wax theatrical. He wants the item, but she holds the purse strings and won't pay the price, or vice versa. Or — perhaps easy for some couples to act — she wants to continue shopping, but he is bored and just wants to leave. Consider the "good cop/bad cop" tactics from a hundred movies.

- As a variant of that, ethnically mixed groups can sometimes turn the common guide's commission system to their advantage. Consider a British husband and Chinese wife meandering about a Chinese market together. What should she do when a vendor assumes she is a tourist guide and offers her a commission to act as translator, and as accomplice in cheating the foreigner? Her best course may be to accept, surprise the vendor by bargaining hard, and later collect her commission to bring the cost down further. Consider the tactics of a "double agent" deceiving one employer in the interests of the other.

- If bargaining for something unique or expensive, such as a good carpet, don't show too much interest in the item you actually want or the vendor will know that's your only choice and price accordingly. Take your time and browse other items. Consider the tactics of a woman "playing hard to get", which she may do even with a man she actually considers fascinating.

- As a variant of that, assure the vendor there is no rush. Encourage him to go off a deal with another customer while you browse, or tell him you don't plan to buy today; you'll just look in several stores and come back next week to actually purchase. This puts more pressure on him if he wants the sale today, or wants to sell to you before you visit his competitors.

- In some cases, you can tell the vendor you'd like to buy, but it's illegal. There are strict international rules on the trade in ivory and products from endangered species, and many nations restrict export of antiques; for example China forbids export of anything older than 1911. If the vendor then admits that the "ivory" is fake or the expensive "Tang Dynasty" vase is actually a modern reproduction, you can use that information in further bargaining. If not, you can moan about the legal risk in an effort to drive the price down.

If the vendor's asking price is absurdly high, by all means laugh or show astonishment in some way. Ideally, ask in the local language if he is crazy or joking. This is not considered rude, provided you smile as you say it, and it indicates to the vendor that you are aware of the item's real value, even if you are not.

Bargaining responsibly

When bargaining, do so responsibly.

Even in cultures where haggling is the norm, many items do have fixed prices. For example, groceries and alcohol usually have fixed prices. Do not haggle when buying e.g. bus tickets; check for a price list in the bus terminal or ask the other passengers in the line or look over the shoulder of the one in front of you to see what the locals pay. Confusingly items in the same category may have a fixed price in one place and be negotiable in another - sometimes within the same country. A taxi fare inside Estelí will have a fixed price. If you want to get a cab in Managua you can haggle and you must agree on a price before getting aboard.

Choose your battles. By all means bargain when buying a carpet from a posh bazaar shop. But if a bottle of water is too expensive, buy it somewhere else.

Don't back out. If you make an offer consider yourself committed to buy if the vendor accepts that price. Don't waste your time or the seller's time bargaining if you have no intention of buying. Even an offer made in jest creates an obligation. As you walk by, the vendor waves a sword worth ¥200 at most and asks for 800. You laugh, say "maybe 100" and walk on. If he calls you back yelling "OK", give him the 100 and take the sword.

Do not let the other person "lose face". Often it is said that "everything is negotiable" - but it isn't. Loss of face is never negotiable. Be aware that the person with whom you are dealing has a family and responsibilities. You are trying to find an agreed position.

Above all, don't take it too seriously; have a sense of humour and know when to accept an offer. Remember that vendors are generally not evil swindlers attempting to trick people out of their hard-earned money; they are often just business people working to support their families.

Bargaining as a problem in game theory

Game theory is a group of mathematical techniques that can be used to analyze almost any human interaction, not just things that are actually games. It has a fairly wide range of applications in both psychology and economics. In particular, it can be applied to almost any situation involving negotiation or bargaining, and it has been; in fact there is a whole branch of the theory that deals with "bargaining games". Disclaimer

The writer here is not an expert in the theory, only a dabbler.

Also, as in any application of a theory to practical problems, there is some risk of oversimplifying or of ignoring aspects of the problem which the model does not cover, although there is often also some chance of the theory suggesting useful ways to look at the problem.

A basic part of the theory is a distinction between different classes of game:

- In a zero-sum game, the total value at stake does not change:

- Five poker players who each bring $1000 to the table. Some players may have a profit and others a loss, but the sum of all profits and losses is always zero. No matter how the game goes, there will still be a total of $5000 at the end.

- Chess at 1 point for a win, zero for a loss and half for a draw. Total score always equals the number of games, whatever happens on the board.

- In a non-zero-sum game, the total value involved changes:

- a good marriage can be a fine thing for both partners (a "win-win" situation)

- a bad marriage can make both partners exceedingly miserable

- some business deals are good for both companies

- some wars damage both nations without producing any noticeable positive effects ("lose-lose"?)

- A mixed game has both zero-sum and non-zero-sum components:

- The scoring for chess is zero-sum, but other parts of the situation are non-zero-sum; both players may be paid to compete and both may be exhausted after a match.

- The scoring for a boxing match is zero-sum, but both fighters may be injured.

Bargaining is a mixed game.

- If you pay $70 instead of $50 for an item, the vendor gets $20 more and you have $20 less in your pocket; this is clearly zero-sum.

- Overall, the goal is to reach a deal that is good for both players; the vendor gets a sale and you get the item. This is a classic win-win outcome, clearly non-zero-sum.

The two goals are basically in conflict; reaching a deal may require the buyer paying more or the vendor accepting less. Sometimes the conflict is not reconcilable without a major sacrifice by one player. In those situations, the best solution is to walk away. You should not want to make such a sacrifice yourself and cannot expect one from the vendor.

When haggling, your goal is not to "win", or just to get the lowest possible price, or to eliminate the vendor's profit, but to find a mutually satisfactory price.