Georgian cuisine

Georgian cuisine

Georgian cuisine is very varied. In addition to its many famous meat dishes, there are also a range of vegetarian and vegan dishes. During Soviet times, Georgian cuisine was seen as the haute cuisine of the Soviet Union. During the 20th century, countless Georgian dishes found their way into the local cuisines of Soviet republics and Eastern European countries.

Georgian cuisine is very varied. In addition to its many famous meat dishes, there are also a range of vegetarian and vegan dishes. During Soviet times, Georgian cuisine was seen as the haute cuisine of the Soviet Union. During the 20th century, countless Georgian dishes found their way into the local cuisines of Soviet republics and Eastern European countries.

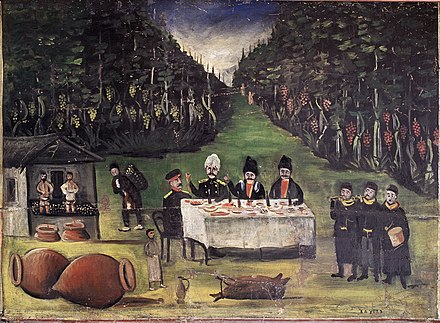

Eating in Georgia can take the form of a big ceremony, and the traditional festive dinner supra is a remarkable experience for travelers. The country is also known for its mineral waters and for its wine: it has a long tradition of grape growing and considers itself the "cradle of viticulture".

Dishes

Bread

The dominant bread (პური, puri) type in Georgia is white bread. Dark bread is known as a "German specialty" and only occasionally available. In addition to the industrially made breads, there are some traditional variants to try out:

The dominant bread (პური, puri) type in Georgia is white bread. Dark bread is known as a "German specialty" and only occasionally available. In addition to the industrially made breads, there are some traditional variants to try out:

-

Tonis puri (თონის პური): This is a flatbread baked in a special stone oven, the tone (თონე), which is heated by electricity, gas or charcoal. The lens-shaped dough is placed on the hot stone for a few minutes and then removed using a long hook – which also creates the small hole in the middle of the bread. Tonis puri is can be eaten hot (fresh out of the oven), or cold. Almost any festive meal include cold tonis puri, as do many informal meals. Modern tone are made of concrete and they can be found everywhere both in the countryside and cities. In bigger cities, there can be several tones in a city block. These small bakeries are recognized by simple, handmade signs saying თონე and can be found in backyards or garages of city blocks. Some upscale restaurants also have their own tones, for instance Puris Sachli ("bread house") in Tbilisi.

-

Shotis puri (შოთის პური): An elongated type of tonis puri, mostly eaten in Kakheti. Even Georgians don't see any difference between these two breads other than their form.

-

Lavash (ლავაში): Very thin flatbread, not just a Georgian bread but common from Turkey to Central Asia and used for wrapping of kababi. Lavash is often baked in tones, and is most widespread in areas with Armenian or Azeri inhabitants.

-

undefined (მჭადი). Cornbread often eaten together with Lobio. A version with cheese mixed in the dough is called Chvishtari (ჭვიშტარი) 2020-11-13

-

(Tarkhunis) Ghvezeli – A quick snack, pastry stuffed with meat, potatoes, cheese or other ingredients, usually sold in markets and on the side of the street.

-

Nazuki – A sweet and spicy bread with cinnamon, lemon curds and raisins. Commonly found in Shida Kartli, especially in Surami.

Khachapuri

Khachapuri (ხაჭაპური), cheese-filled bread or pie, is one of the standard dishes in Georgia and one of the national dishes, if not the national dish. Khachapuri literally means "pot bread", but "cheese bread" is a more apt description. The dough is rolled out, covered with cheese, and baked. This rich pie is eaten at almost any kind of occasion: as a streetside snack, as an appetizer, or even as a meal in itself (mostly as breakfast). Best eaten fresh out of the oven, but also good cold, as in after a supra.

There are many varieties of khachapuri. The Imeretian version is widely available all over Georgia, the one that's referred to as just "khachapuri", and it belongs to the "standard repertoire" of Georgian cuisine. As a matter of fact, there's a Georgian consumer price index known as the Khachapuri Index which compares the costs of the ingredients in an Imeretian khachapuri between different regions.

A khachapuri in a restaurant is usually the size of a pizza and can be shared between two-four people. A typical tourist mistake is to order one for each person, only to realize that it's too much to eat. Moreover, it's not ordered on its own but in combination with other dishes like salads or meat.

Variants of khachapuri include:

- Khachapuri Imeruli (ხაჭაპური იმერული): The standard version, round like a pizza and stuffed with Imeretian cheese. The quality (and price) depends on how much cheese is used. Street food versions that sell for around three lari don't contain that much cheese, whereas a good khachapuri at an eatery would cost the double.

- Khachapuri Megruli (ხაჭაპური მეგრული): The Mingrelian version is also widely available and popular. Here sulguni cheese is used, and there's cheese both inside and on top of the pie. A good Mingrelian khachapuri in an eatery would cost around 8-10 lari.

- Khachapuri Adjaruli (ხაჭაპური აჭარული): The Adjarian version looks a bit different: it's formed like a ship, filled with sulguni cheese and one or more eggs before baking in a wood oven. When taken out of the oven, butter is added on top of it. Before eating, you should mix the three stuffings and be careful that you spill as little as possible of it. In restaurants, this khachapuri is often available in several sizes. Iunga (lit. ship's boy) is the smallest one, botsman (lit. sailor) is the normal version, and bigger versions carry names such as Titanic or Aurora. Even if the Adjarian "ship" may look small, the stuffing fills you up, and most people would need to be really hungry to eat a normal version. You can find Adjarian khachapuri in restaurants around the country, but outside of their "native" southwestern Georgia they may not be so good. In Adjaria such ships will cost around 6 lari for a standard sized version.

- Guruli originated in Guria region. It's made with egg and cheese.

- Khachapuri Penovani (ხაჭაპური ფენოვანი): Made with laminated dough, filled with cheese and as it's a smaller khachapuri, it's popular as a street snack. You can find them at bakeries, markets, bus stations and supermarkets for 1.50 lari upwards.

- Khachapuri Osiuri (ხაჭაპური ოსიური): The South Ossetia version filled with a mixture of cheese and potato puree.

- Khachapuri Rachuli (ხაჭაპური რაჭული): The version from Racha (in the north) is filled not only with cheese but also ham or bacon.

- Khachapuri Shampurse (ხაჭაპური შამპურზე): This one isn't baked in an oven, but placed on a skewer (შამპური, shampuri) and roasted on open fire. Particularly popular in mountainous regions.

- Moreover there are many local versions; for example, restaurants may have their own "house style" khachapuri (საფირმო ხაჭაპური, sapirmo khachapuri).

Lobiani

Lobiani (ლობიანი) is another pie that can be regarded as one of Georgia's national dishes. It originates from Racha but is popular all over the country. Instead of cheese, it's filled with beans (ლობიო, Lobio), and is also a vegan alternative to khachapuri. Many Georgians observe Eastern Orthodox fast days, during which they abstain from meat, milk and egg products, and then lobiani is particularly popular.

There are also some variants of lobiani:

- The regular lobiani is spiced bean paste baked in a bread. It will cost around 4 lari in restaurants.

- Rachuli Lobiani (რაჭული ლობიანი) or Lobiani Lorit (ლობიანი ლორით) also includes bacon or pork rind, and hence is not suitable for times when you want to avoid meat.

- Lobiani Penovani (ლობიანი ფენივანი) is much like khachapuri penovani made with laminated dough and popular as a street snack. You can usually buy them for less than 1 lari.

Dairy products

.jpg/440px-Cheese_selling_(Photo_by_Peretz_Partensky,_2009).jpg) Dairy production in Georgia is mostly in the hands of small farmers. Industrially produced dairy products that you can buy in supermarkets are mostly imported or made from imported milk powder. Authentic products are easily bought directly from the farmers in the villages. Nevertheless, be careful, as your stomach may not be prepared for non-pasteurized dairy products. Markets are another good place to find such products. Names of diary products include:

Dairy production in Georgia is mostly in the hands of small farmers. Industrially produced dairy products that you can buy in supermarkets are mostly imported or made from imported milk powder. Authentic products are easily bought directly from the farmers in the villages. Nevertheless, be careful, as your stomach may not be prepared for non-pasteurized dairy products. Markets are another good place to find such products. Names of diary products include:

- Matsoni (მაწონი). - like yogurt but with a higher fat content and more solid.

- Khacho (ხაჭო). It is quark (cottage cheese), quite dry and brittle, with a fat content of 6-9%. 9-10 lari/kg

- Arazhani (არაჟანი) - sour cream, usually with a fat content of at least 20%, indispensable for Russian dishes like borscht or pelmeni but also a basis for many sauces.

- Karaki (კარაქი). Butter. 14 lari/kg

- Rdze (რძე) - milk

- Nadughi (ნადუღი). Resembles cottage cheese but is much more creamy and has a different taste. It's composed mostly of albumin proteins and it could be called a dietetic product. Georgians love to eat it mixed with mint. Nadughi is mostly prepared in the western parts of Georgia. 5-6 lari/kg

Cheese

Much of the milk produced in Georgia is made into cheese (ყველი, k<sup>h</sup>veli). There are many types of cheese, but the variety isn't that abundant compared to other types of dishes in the Georgian cuisine.

- undefined (სულგუნი). Hard cheese in brine with varying saltiness. Cheese structure is very similar to block mozzarella. It's available as smoked or as strings of cheese formed into braids. 15-16 lari

- Smoked sulguni (სულგუნი Შებოლილი). 17–18 lari/kg

- Imeruli (იმერული). like sulguni but more brittle

- Guda (გუდა, გუდის ყველი — "cheese from sack").

- Meskhuri (მესხური) - a specialty from Samtskhe-Javakheti, this cheese has very high fat content and is almost comparable to butter. In markets, it will cost about 8-12 lari per kilo.

- Dambalkhacho (დამბალიხაჭო). This is a molded cheese made from buttermilk. It officially originates from Pshavi and Tianeti regions, North-East Georgia. It is cooked with a technique that was declared intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2014. This cheese has been in use since the 17th century at least.

- Tenili (ტენილი). A Meskhetian cheese made from sheep's milk, also considered to be UNESCO culture heritage. Tenili is made of threads of rich sheep's milk cheese briefly brined before being pressed into a clay pot. The monastery in Poka (Ninotsminda region) has a modern cheese factory producing very good non-Georgian varieties of cheese, like blue cheese, though their prices are quite steep.

Meat

Khinkali

The filled dumplings khinkali (ხინკალი) is another iconic Georgian dish and plays a central role especially in the cuisine of the eastern parts of Georgia. Among Tbilisians it's popular to make trips to khinkali restaurants in the region around Mtskheta and Dusheti, to enjoy them in the home region of the dish.

Khinkali is reminiscent of dumplings from other cuisines such as pelmeni or baozi, but have their own distinct taste. A dough is made from flour, water, salt and optionally eggs. Small circular pieces are cut out with a glass, filled with a spiced ground meat, folded, boiled in brine, and served with butter and black pepper. Especially the folding of the khinkali is an art in itself and it's important to fold it so that it doesn't open during the boiling. It's not uncommon for deep frozen khinkali bought at supermarkets to open and the filling coming out when you heat them.

Khinkali is eaten by hand, and it will take some practice to do it right - once you've learned it as a foreigner you will impress the locals. Grab the top, which locals call kudi (ქუდი, lit. "hat"), or tschipi (ჩიპი lit. "navel"), and when you take the first bite, suck out the juice so that it doesn't spill. If this is the first time eating khinkali there's a good chance you will spill some of it on the table and your clothes. Then you eat the rest, and while you can eat the "hat", most Georgians leave it on the plate. Fork and knife can be used to grab and bring the khinkali to your mouth, but cutting it up on your plate is a no-no. Competitive khinkali eating is a popular hobby among Georgian men, and the winner is decided depending on who's left most "hats" on the table.

There are two varieties of khinkali:

There are two varieties of khinkali:

-

Khinkali Kalakuri (ხინკალი ქალაქური, town khinkali): the standard version you can expect in restaurants with thicker "hat" and less spicy.

-

Khinkali Mtiuri (ხინკალი მთიური, mountain khinkali): in rural eateries, especially in the mountains, this type is served. It has a thin, short hat has more spices and herbs in the filling.

If your khinkali dinner has went on for hours and the khinkali has gotten cold, they can be reheated in a frying pan. Also in restaurants they will be happy to do this.

The filling normally consists of ground meat (beef and/or pork) spiced with onion, garlic, pepper and salt, and often also with fresh coriander, parsley or caraway. Vegetarian versions with quark (curd cheese) or potatoes are also popular but not available everywhere.

While wine is the drink commonly associated with Georgia, it's not a common drink with khinkali, beer or occasionally vodka is prefered. Also, khinkali is a dish that is ordered on its own, sometimes with a side salad. They are ordered by number for your party, about 5-7 khinkali will suffice for each guest, even if they're hungry, so if you're a party of four persons you would want to order 20-25 of them. A single khinkali will usually cost around 0.70 lari, less — in the countyside, and more — in upscale restaurants. They're made to order, and will take about 20-30 minutes to make, and if you want hundreds of them for a bigger party you should make your order several hours beforehand.

Mtsvadi

Mtsvadi (მწვადი) - internationally better known by its Russian name shashlik - is as popular in Georgia as elsewhere in the region, and the most popular barbecue dish. Mtsvadi is not just a favorite choice when eating at a restaurant, but also on picnics, when sitting around a campfire or having a garden party.

Georgian mtsvadi is not much different from the same dish in the surrounding countries. The meat is cut into palm-sized pieces, marinated and spiced, including being immersed for several hours or overnight in a mixture of onion, wine and often pomegranate juice and seeds and berberis. The meat is stuck on skewers, roasted on glowing charcoal (preferably from grapevine), and served with fresh onions.

Some important words:

-

Samtsvade (სამწვადე) - literally "for mtsvadi", meat that's readily cut for this purpose but not marinated.

-

Basturma (ბასტურმა) - when the meat has been marinated, available in larger supermarkets

-

Shampuri (შამპური) - the skewer. If you have to buy skewers, avoid the ones that bend easily. A good choice are Soviet-made skewers that you can find on flea markets; you'll recognize them on the engraved original price.

-

Tsalami (წალამი) - grapevine cut and dried to use as firewood for mtsvadi. Wine growers save these for mtsvadi, though they are available in some shops as well. When you light tsalami, beware that they first burn with a hot and high flame. This will go on for a few minutes, then you're left with hot charcoal that will keep glowing for a long time. Then, put the skewers a few centimeters above the charcoal.

-

Mtsvadi - the dish itself, available as:

-

Ghoris mtsvadi (ღორის მწვადი) - pork

-

Khbos mtsvadi (ხბოს მწვადი) - veal

-

Katmis mtsvadi (ქათმის მწვადი) - chicken

-

Tskhvris mtsvadi (ცხვრის მწვადი) - lamb

-

Mtsvadi kezse (წვადი კეცზე) - mtsvadi made in a pot (კეცე, Keze) on a stove or open fire.

-

If you can't make a fire, mtsvadi can also be made in a frying pan.

Other meat dishes

-

Shkmeruli (შქმერული) is fried chicken in a sauce made of milk and garlic. Often the chicken is first boiled and then fried. It's eaten hot.

-

Satsivi. – Chicken in walnut sauce.

-

Mtsvadi. – Like Shashlik, tasty grilled chunks of marinaded pork or veal on skewers with onions, is another staple.

-

Kupati. – A spicy sausage popular all over Georgia.

-

Kuchmachi. – A dish made from chicken livers, hearts and gizzards, with walnuts and pomegranate seeds for topping.

-

Chanakhi. – A stew made out of lamb, tomatoes, aubergine, potato and spices, and simply delicious.

-

Chakapuli. – A stew made from lamb chops or veal, onions, tarragon leaves, cherry plums or tkemali (cherry plum sauce), dry white wine, and mixed fresh herbs (parsley, mint, dill, coriander), equally good.

-

Chakhokhbili. – The word means pheasant, but it's stewed chicken and tomatoes with fresh herbs.

-

Chikhirtma. – A soup almost completely without any vegetables, made with rich chicken broth, which is thickened with beaten eggs and lemon curd.

-

Chashushuli – Beef stew with tomatoes, similar to but better than goulash.

-

Ojakhuri – The word means meat and roasted potatoes. Usually comes with pork, but vegetarian mushroom ojakhuri is not unheard of.

-

Kalia – A hot dish made from beef, onions and pomegranate.

Vegetarian dishes and salads

There are lots of vegetarian dishes (mostly in western parts of Georgia) which are quite tasty and accompany most of local parties with heavy wine drinking. However, vegetarianism as such is an alien concept to Georgians, even though the Georgian Orthodox Church obliges its followers to "fast" at various times of the year including the run up to Christmas (7th January). Such fasting means abstaining from meat and eating vegetables and dairy.

- Ajapsandali. (აჯაფსანდალი) – A sort of vegetable ratatouille, made differently according to each family's recipe, and which is wonderful.

- Lobio. (ლობიო) – Like a local version of hummus, made from beans (cooked or stewed), coriander, walnuts, garlic, and onions, though some variants of lobio are closer to baked beans than hummus. Order some marinades with it!

- (Nigvziani) Badrijani. (ნიგვზიანი ბადრიჯანი) – A fried eggplant stuffed with spiced walnut and garlic paste, often topped with pomegranate seeds.

- Pkhali. (or mkhali ) (ფხალი) – A dish of chopped and minced vegetables (cabbage, eggplant, spinach, beans, or beets), combined with ground walnuts, vinegar, onions, garlic, and herbs.

- Sulguni. (სულგუნი)– A brined, sour, moderately salty flavored cheese with a dimpled texture and elastic consistency from the Samegrelo region. Often served as side dish.

- Ghomi and Baje (ჭომი და ბაჟე) – Made of cornmeal and corn flour, similar to porridge, usually served with melted cheese inside. Try it with baje, a nut sauce.

- Chvishtari (ჭვიშტარი) – Similar to Ghomi, but baked. Basically mchadi made with Sulguni cheese.

- Soko Ketsze (სოკო კეცზე)– Oven-fried mushrooms in a clay pan.

- Akhali Kartopili (ახალი კარტოფილი) – Young potatoes roasted, mostly in early May.

- Kitris da Pomidvris Salata Nigvzit (კიტრი და პომიდვრის სალათი ნიგვზით) is available in pretty much every restaurant. It's a tomato and cucumber salad with a creamy walnut dressing.

- Jonjoli (ჯონჯოლი) is a salad of bladdernut buds. They're picked in April before bloom and put into brine. The taste is like a combination of olives and capers.

- Qatmis Salati (ქათმის სალათი) is a chicken salad with chopped chicken, onion, mayonnaise and spices.

- Pkhali (ფხალი), something between a salad and a spread, made from pureed walnuts and vegetables like spinach or beets.

Sauces

Try these sauces, both with vegetarian and meat dishes:

- Masharaphi (მაშარაფი) – Pomegranate sauce

- Tkemali (თყემალი) – Plum sauce

Spices

- Svanuri marili (სვანური მარილი) is a spice mix made of salt, garlic, fenugreek, dill, coriander, caraway, ground paprika and tagetes. It's used in almost every kitchen, as a condiment for soups, potatoes, breads, vegetables and meat, and is also a nice souvenir.

Sweet dishes

-

Churchkhela (ჩურჩხელა). a snack popular all over Georgia. Nuts (walnuts or hazelnuts) are put on a string and dipped in a mixture of grape juice and flour, then placed to dry, and finally covered with one more layer of flour. It's rich in energy, doesn't spoil easily, and was historically a food for shepherds and soldiers. Fresh churchkhela is soft, but it hardens over time. While it eventually will become difficult to bite it still remains edible.<br/>The color of churchkhela ranges from light yellow to dark red, depending on the type of grapes the juice was made of. As they in their final form are covered with flour, they look a bit like dried sausages. Churchkela is available on markets and from streetside vendors and costs 2-3 lari. The string holding them together is not edible; break the churchkela in half and pull out the string before eating. 2023-03-30

.jpg/440px-Churchkhela_(1).jpg)

-

Gozinaki (გოზინაყი). A confection made of caramelized nuts (usually walnuts), fried in honey, but served exclusively on New Year's Eve and Christmas. 2023-03-30

-

Tklapi (ტყლაპი). A puréed fruit roll-up leather, spread thinly onto a sheet and sun-dried on a clothesline. It can be sour or sweet. 2023-03-30

-

Pelamushi (ფელამუში). A porridge made during harvest time with flour and pressed, condensed grape juice. 2023-03-30

-

Korkoti (კორკოტი). Wheat grains boiled in milk with raisins. 2023-03-30

-

Kaklucha – Hard to find, also called Pearls of the Sun, caramelized walnuts.

-

Nugbari – Candy and also the brand name.

-

Georgian baklava – Looks like a nutsack but contains starch and walnuts, and can be found in some of the bakery kiosks around Tbilisi. Not as far as sweet as the Turkish alternative of the same name, and great with a coffee. About 2.70 lari.

Fruit and vegetables

The fruits and vegetables here are bursting at the seams with flavor, and are very cheap. Specifically grown in this region and a must are kaki (persimmon), feijoa, pomegranate and grapes. Also try dried fruits, available at many markets.

| Fruits | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strawberry | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| sweet cherry | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| cherry plum | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| mulberry | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||

| plum | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||

| apples | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||

| pear | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||

| fig | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| nectarine | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| apricot | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| peach | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| watermelon | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| melon | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| grape | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||

| persimmon | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| kiwi | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| feijoa | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| pomegranate | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| quince | style="background:#ff867c;" | style="background:#ff867c;" | |||||||

| medlar | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||||

| lemon | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||||

| tangerine | style="background:#ff867c;" | ||||||||

| orange | style="background:#ff867c;" |

Even if you only speak English and stand out as a foreigner like a slug in a spotlight, you can get fruit and vegetables in the market for a mere fraction of what you would pay in, say, Western Europe. Grabbing a quick meal of tomatoes, fresh cheese, puri (bread), and fruit is perhaps the most rewarding meal to have in the country.

Kaki / persimmon

This fruit comes in two types—astringent and non-astringent. Astringent ones such as the hachiya will leave your mouth very dry and puckered if not completely ripe, due to the high amount of tannins. They are also generally darker. Non-astringent ones such as fuyu and jiro are perfect to eat fresh; they are juicy and sweet and do not generally need much additional ripening. The latter ones are also the ones distributed in Western Europe, because the former ones are hardly transportable in their soft state.

Popular non-Georgian dishes in the country

- Pelmeni and varenniki/pierogi

- Borscht

- Pizza

Drink

Wine

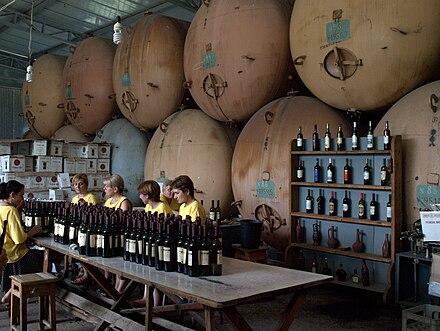

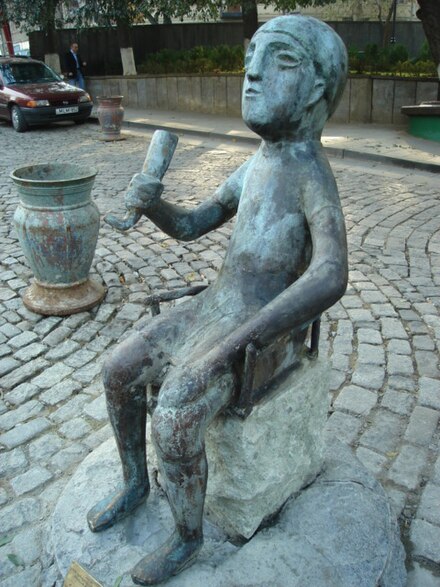

Georgia is one of the countries wine-growing originates from. The area has a history of wine-growing going back 8,000 years and considers itself the "cradle of wine-growing". According to some linguists, the word for the beverage "wine" (vin, vino, Wein...) originates from Georgian ღვინო (Ghwino).

Large parts of the country are suitable for wine growing, and both domestic and international grape varieties are grown. It's the second biggest export product of Georgia (after scrap metal). During Soviet times, wine produced in Georgia and Moldova was drunk all over the Soviet Union and beyond, and still today the countries formerly making up the USSR are the main export areas. Elsewhere in the world (e.g. Western Europe) Georgian wine is limited to more expensive types that Georgian restaurants and specialty shops import.

Wine is not just a beverage, but a cornerstone of Georgian everyday culture and a point of national pride. For example many gravestones are decorated with vine or grapes, and the monumental Kartlis Deda ("Mother Georgia") statue holds a cup of wine for welcoming guests in her left hand and a sword to fend off enemies in her right hand.

At big family banquets like weddings, funerals and baptisms, the host needs to make sure there's enough wine for the guests. During such events it's consumed in great quantities, sometimes from different cups and drinking horns and always together with toasts. This is also true for informal events and meetings. At big events the host should get at least two liters of wine for each adult male guest, and it is considered shameful if the host runs out of wine before the party is over. At banquets there's always a tamada (a master of ceremonies) who is responsible for the toasts and keeping order at the tables. Wine consumed at such events is nevertheless lighter and has a lower alcohol content than normal wine.

In addition to the many commercial wines, home-made wine is also widespread. Almost all families have a small country house where they grow their own wine, and in urban environments, too, you may see grapevines growing in backyards. Wine harvests (თველი, Tweli) often take place twice, in late September and late October, and at that point family and friends come together to help with the wine-making. The grapes are cut, placed into big buckets (მარანი, Marani) and pressed or trampled to extract the juice ((მაჩარი, Matschari). Then the juice, often together with the pomace, is poured into glass jars, plastic tanks, or more traditionally, into amphoras that are dug into the ground. After a few weeks, the wine is ready and is drunk from mid-December onwards. The big wine cellars in Georgia operate the same way.

Wine-growing areas and grape varieties

The main wine production areas are:

The main wine production areas are:

-

Kakheti, including the Alasani and Iori valleys, is Georgia's most important wine region, and about 2/3 of Georgia commercially-produced wine comes from here. The main grape varieties grown here are rkaziteli (white) and saperawi (red). Notable denominations of origin include Achmeta, Kvarelo-Kindsmarauli, Manavi, Napareuli and Zinandali. Famous vineyards in the region include Schuchmann and Manavi in Telvai, and in Zinandali there's a large wine museum.

-

Mtskheta-Mtianeti, Tbilisi, Kvemo Kartli and Shida Kartli: In the wide floodplain between Khashuri and Tbilisi, mainly European grape varieties are grown, for wines that are exported and for brandy and sparkling wine. Some famous vineyards in the region are Château Mukhrani and Tbilvino in Tbilisi, where you can also find the Bagrationi sparkling wine factory and Sarajishvili brandy factory. In Assureti, Schala wine is produced, from a grape type cultivated by the Caucasus Germans.

-

Imereti: Many grape varieties are grown in the Rioni and Kvirila River valleys, but one specialty is the white Zizka.

-

Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti: Near the sources of the rivers Rioni and Zcheniszkali, grapes with a high sugar content are preferred. Khvanchkara is known for the wine by the same name, which is made from the grape types alexandruli and mudschurtuli. It was reputedly Stalin's favorite wine, and it remains popular in the countries formerly making up the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the wine-growing area is relatively small, and as such many cheaper "khvanchkara" wines (both sold in Georgia and abroad) may not be from the region at all, or at best be mixed with wine from other regions.

-

Western Georgia is famous for sweet wines produced for local consumption.

Home-made wine is produced everywhere in Georgia where wine grows, meaning everywhere but in the highest mountain regions.

Wine tourism

Bigger wine growers have on-site shops, and offer wine cellar tours and wine tastings, sometimes together with fine dining. Particularly the Kakheti wine producers have opened up their sites for visitors and have developed a wine route itinerary through the region.

In addition to the wine harvest, another important related event is the Festival of the New Wine, talking place each May in the square outside the Ethnographic Museum in Tbilisi. Both big and independent wine producers sell their wine there, both wholesale and to individual consumers, and there are food stalls and traditional music and dance performances.

Buy

A bottle of good Georgian wine in a shop can be surprisingly expensive (from 10 lari upwards). However, good home-made wine can be bought from street vendors starting from 2 lari per liter, but ask to taste it before you decide to buy. Also, this wine doesn't store very well, so you may want to pour it into smaller bottles and close them air-tight, otherwise it will spoil within days. Georgians commonly save plastic bottles for transportation of home-made wine.

Other alcoholic drinks

Liquor

Making distilled beverages from the by-products of wine-making is also popular. The most common of these is chacha (ჭაჭა), a pomace brandy comparable to Italian grappa or Bulgarian rakija. Chacha is made both industrially and at home; distilling spirits for your personal use is legal in Georgia. It can also be made by distilling juice from other fruits, in which case it's called araki (არაყი) - like Turkish Rakı.

Making distilled beverages from the by-products of wine-making is also popular. The most common of these is chacha (ჭაჭა), a pomace brandy comparable to Italian grappa or Bulgarian rakija. Chacha is made both industrially and at home; distilling spirits for your personal use is legal in Georgia. It can also be made by distilling juice from other fruits, in which case it's called araki (არაყი) - like Turkish Rakı.

Due to Russian influence over the centuries, vodka is also popular, and it's also known as araki (which indeed is a general term for liquor in Georgian, much like the suffix "ju" in Korean). Popular domestic vodka brands are Gomi and Iveroni, and imported Ukrainian and Russian vodkas are also widespread. The third common distilled drink is brandy (კონიაკი, Koniaki).

Liquor is only drunk at informal occasions, and is never drunk together with wine, though liquor and beer are commonly enjoyed together. Also here the Georgian drinking etiquette applies, and there may be a master of ceremonies making toasts.

Beer

.jpg/440px-Kazbegi_(9458110927).jpg) Beer (Georgian: ) has a tradition of hundreds of years in the mountains of Georgia, and there it has been used as replacement for wine during religious festivities. Beer is still brewed the traditional way, but that beer is only available during these events. Given Georgia's strong wine culture, the rest of the country doesn't have a beer drinking tradition. There, beer amounts to the not-so-impressive products by a few big breweries, though the standard has improved as they've started brewing European brands under license.

Beer (Georgian: ) has a tradition of hundreds of years in the mountains of Georgia, and there it has been used as replacement for wine during religious festivities. Beer is still brewed the traditional way, but that beer is only available during these events. Given Georgia's strong wine culture, the rest of the country doesn't have a beer drinking tradition. There, beer amounts to the not-so-impressive products by a few big breweries, though the standard has improved as they've started brewing European brands under license.

Almost all domestic beer you'll find in supermarkets come from one of these four breweries in Greater Tbilisi:

- Natakhtari - in Natakhtari, part of the Turkish Efes group

- Zedazeni (dead link: January 2023) - in Saguramo, brewing e.g. König Pilsner under license

- Castel Sakartvelo (dead link: December 2020) - in Raion Isani-Samgori in eastern Tbilisi, brewing the popular Argo beer

- Kazbegi - in Tschughureti in central Tbilisi, it's market share has shrunk over the years

A few smaller breweries exist, like OzurgetLudi in Osurgeti, Bolnisi in Bolnissi and Batumuri in Batumi, but it will take some effort to find them even in the cities they're brewed. Brewery tours are unheard of, though some of the breweries may have their own shops.

Beer is often drunk together with vodka or chacha. The toast is mostly made with the liquor and the beer plays just a secondary role. In fact toasting with beer used to be forbidden on religious grounds, though patriarch Ilia II voided this ban in order to make the Georgians consume less liquor. When a toast is made with beer, Georgians often say the opposite of what they mean, like toasting to Vladimir Putin during and after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.

Beer doesn't have any place in a Georgian banquet (supra, see below), but is enjoyed in informal settings such as when watching football. Khinkali is the only Georgian food commonly associated with beer; another snack is dried and salted fish sometimes sold next to brewery shops. Beer is also associated with German cuisine (which is fairly popular) and consumed together with food like schweinshaxe or bratwürste with sauerkraut.

Some beer related vocabulary:

- Ludi (ლუდი) - beer

- Ludis Bari (ლუდის ბარი) - "beer bar", or (ლუდჰანა Ludhana), "beer house". An establishment specializing in serving beer. Usually they offer a range of imported beer at a comparatively high price. The beer bars and beer houses that serve food usually serve German fare as per above.

- Ludis Maghasia (ლუდის მაღაზია) - beer shop. Not just selling beer but also food commonly consumed with beer (in Georgia).

Non-alcoholic drinks

Soft drinks

Wine isn't the only beverage Georgians have pioneered, it's a little known fact that some of the earliest soft drinks were invented here. In 1887 the Tblisian pharmacist Mitrophane Laghidse was developing a cough medicine and tried mixing soda water and tarragon. The result was a soft drink that quickly became popular in Georgia and all over the Russian Empire and has remained so until this day. Also more variants were invented and manufactured the same way (syrup and soda water). But it would take until 1981 for mass production of soft drinks to begin in the Soviet Union.

Wine isn't the only beverage Georgians have pioneered, it's a little known fact that some of the earliest soft drinks were invented here. In 1887 the Tblisian pharmacist Mitrophane Laghidse was developing a cough medicine and tried mixing soda water and tarragon. The result was a soft drink that quickly became popular in Georgia and all over the Russian Empire and has remained so until this day. Also more variants were invented and manufactured the same way (syrup and soda water). But it would take until 1981 for mass production of soft drinks to begin in the Soviet Union.

Soft drinks (ლიმონათი), Limonati (like in some other European languages "lemonade" is an umbrella term for all soft drinks with or without lemonade) are today an important part of Georgian meals, even banquets. Traditional fruit soft drinks are more popular than the global brands. The big breweries all make soft drinks, but there are also smaller manufactures. Popular traditional soft drink flavors are tarragon (ტარხუნა, Tarchuna), pear (მსხალი, Ms'chali), grape (Traube, საფერავი), cream and berberis.

The best place to try out traditional soft drinks are in coffee houses of the "Laghidze" company. The coffee house chain was founded by the inventor of the Georgian lemonade, and the beverages are produced in a factory by the same name, fresh from syrup and soda water. Home-made soft drinks are sold at markets, and made to order (price for a glass 0.30 lari). Some brands of industrially produced soft drinks (from the same flavors) are Natakhtari, Zedazeni, Kazbegi und Zandukeli.

Water

The Caucasus mountains are home to many mineral water sources. Mineral water is bottled and exported, and is especially popular in the former Soviet states and the former Eastern Bloc in general. It's also one of Georgia's main export products; for example in 2013 the country exported mineral water for USD 107 million.

The main mineral water brands:

- Borjomi - the classic brand from the spa town by the same name, particularly popular in Russia and other former Soviet countries.

- Nabeghlavi - Borjomi's main competitor in the domestic market, has started exporting its water as well. It too comes from an eponymous spa town.

- Likani - from a source near Borjomi, and the third most popular mineral water brand in Georgia.

In shops you can also buy non-carbonated water (also from spa water), some important brands include Bakhmaro, Sno and Sairme. Georgian mineral water always has a high carbon dioxide, mineral and iron content. It's an acquired taste, much stronger than for instance Central European mineral waters, but is an excellent beverage during hot summer days as it contains many minerals that are useful if you're dehydrated. Finally, Georgians also consider mineral water a good hangover cure.

In addition to bottled water, the country also has countless natural mineral water sources when you can enjoy the water free of charge, as much as you like. Reddish and yellowish rock sediments often reveal that there's a mineral water source nearby.

When ordering just water (წყალი}}, Zk<sup>h</sup>ali) in a restaurant you will get non-carbonated water. If you want "real" mineral water, ask for it by the brand name. If they don't have your preferred brand in stock, they will let you know, and suggest you another mineral water brand.

Tea

Georgia was the main tea (ჩაი, tchai) growing area in the Soviet Union, and "Gruzian chai" was also famous in western countries. Tea production virtually ended in the early 1990s, and many former tea plantations have grown over. Today tea is grown on a small scale, and most of it is imported. Still, in Ozurgeti there's a tea museum and a trade school for tea growing. Georgian-produced tea can be bought (by weight) on markets, and the company Gurieli makes tea bags with Georgian tea that are sold in most supermarkets.

Georgia was the main tea (ჩაი, tchai) growing area in the Soviet Union, and "Gruzian chai" was also famous in western countries. Tea production virtually ended in the early 1990s, and many former tea plantations have grown over. Today tea is grown on a small scale, and most of it is imported. Still, in Ozurgeti there's a tea museum and a trade school for tea growing. Georgian-produced tea can be bought (by weight) on markets, and the company Gurieli makes tea bags with Georgian tea that are sold in most supermarkets.

While production has subsided, tea remains a popular drink, particularly black tea sweetened with muraba (a kind of jelly with big fruit pieces). Mzvane (მწვანე) stands for green tea, schawi (შავი) and tchai (ჩაი) for black tea. Traditionally tea water was made in samovars like in Russia, today electric water cookers and gas stoves are used.

Coffee

Coffee (ყავა, K<sup>h</sup>ava) is widely drunk, but there's no such coffee culture like in nearby Armenia or Turkey. Traditionally coffee is made the Turkish way and called Nalekiani Khava (ნალექიანი ყავა) or Turk<sup>h</sup>uli K<sup>h</sup>ava (თურყული ყავა), where ground coffee beans, sugar and water are heated in a pot. Together with electric coffee makers this is the normal way of preparing coffee; also instant coffee is available.

Until the early 2010s, Italian coffees like espresso and cappuccino were just a specialty to be found in expensive restaurants. But after that coffee houses specializing in Italian coffees (often open day and night) have sprung up in bigger cities. Thanks to this, prices have dropped considerably (cappuccino 3 lari, espresso 2 lari) and Italian coffees have found their way into other restaurants, though there they may still be relatively expensive; even 6 lari and up. Also, if you're a coffee connoisseur, be sure to ask what kind of coffee they make before ordering, otherwise you may be in for a cup of instant coffee at an inflated price.

Signs above coffee houses generally don't say "café" in Latin letters, but კაფე, kape. (ყავა, K<sup>h</sup>ava) is the beverage.

Popular drinks from nearby countries

-

Burachi (ბურახი) is Russian kvas. It's a carbonated soft drink, related to beer, with a low alcohol content (max. 1.5%) and a taste of herbs. Burachi is most widespread in bigger cities in markets, around stations and parks where it's sold from tank carts (often labeled with the beverage's Russian name, Квас). A glass costs about 0.30 lari.

-

Kefir (კეფირი, Kepiri) is a fermented dairy beverage originally from the northern Caucasus, and is part of many Georgians' breakfasts.

-

Ayran (აირანი, Airani) is an East Anatolian and Armenian beverage from yoghurt, salt and water and is popular in Adjaria.

Meals

Restaurant types

- Restorani (რესტორანი): restaurant - mostly upscale, a lot of dishes on the menu.

- Dukani (დუქანი): guesthouse, generally simpler than a restaurant with a shorter menu.

- Sachinkle (სახინკლე): a place specializing in khinkali and at best serving only a few other dishes.

- Sachatschapure (სახაჩაპურე):like the former, but specializing in khachapuri.

- Kape (კაფე): coffee house

- Ludis Bari (ლუდის ბარი), Ludis Restorani (ლუდის რესტორან): beer house, specializing in beer and also serving Central European food and snacks.

- Sasausme (სასაუსმე): fast food and snack place

A Georgian specialty is the Sabanketo Darbasi (საბანკეტო დარბაზი), the banquet or party hall. These establishments are not open for walk-in guests but only for pre-booked banquets (supras) and other events.

Pay

Traditionally the person inviting others for a meal would pay the whole bill. Among friends, mainly in urban environments, this is not necessarily true: sometimes, the final sum is divided by the number of patrons; alternatively, everyone contributes what they like. But giving each patron separate bills to pay for their own food and drink is unheard of.

Credit cards are accepted only at more expensive restaurants and in bigger cities. If you need to pay by card, ask before ordering if the restaurant accepts your card.

As a rule, bigger restaurants add a service fee of 10-20% of the final sum to the bill, though this will be stated in the menu. This means that tipping isn't necessary, but if you're particularly happy about the service, you can round up the sum. Smaller restaurants, especially in the countryside, don't add any service fee, and in this case a bigger tip (around 10%) would be appropriate.

The supra

Supras are sometimes enjoyed in restaurants, but often in special banquet halls as per above. As these events tend to be fairly loud, restaurants often have separate rooms (კუპე, Kupe) for supras to make sure the events don't disturb or get disturbed by other patrons or supras. Restaurants and banquet halls generally allow people to bring their own wine. The host needs to make sure there's not only plenty of wine, but also plenty of food for the guests, and often there will be much food left after the party is over. The host family will get to bring this food home.

Drinking is also an important part of a supra. A supra always features a tamada (ტამადა), a master of ceremonies nominated by the host, who is responsible for the toasts, for keeping the party going and the guests joyful. The tamada has to be charming, funny and spontaneous, but also has to possess a certain amount of authority. They need to make sure that the guests don't split into smaller groups, keep general order and address individual guests behaving badly or seeming lonely. Supras may include a few dozen to several hundred guests, and at bigger events, tamadas often have a microphone and loudspeaker to make themselves heard, or they may have assistants distributing the toasts to individual tables.

You may only drink when the tamada has offered a toast. These are not just random jokes, but remarks that guests take seriously, and sometimes take the form of poetry and songs. During the toast, guests should stop their own discussions and listen to the tamada, as it's a major breach of etiquette to do otherwise. Then, guests are encouraged to add comments to the theme, which can turn into long speeches.

At the beginning of the supra, the toasts are more frequent to get the party started, though the pace slows down as the evening progresses so as to make sure the guests don't get too drunk. The tamada himself may never get so drunk that he doesn't stay in charge of the party, so experienced drinkers are preferred as tamadas. At some parties, the tamada isn't allowed to leave the table, even to go to the toilet.

Topics for toasts vary between supras, but traditional and common ones include:

- To God (უფალის დიდება, Upalis Dideba) - commonly the first toast at any supra

- To peace (Mschwidobis Gaumardschos) - commonly the first toast in Guria

- To the honor of the host or event (if a birthday, baptism, marriage or similar is the reason for the banquet)

- To the host family (Am Odschachs Gaumardschoss) - usually at private events that have no particular theme

- To the children - not only the ones at the party, but to all children in the world

- To friendship - between guests as well as their friends that aren't present

- To love (Sichwaruls Gaumardschoss) - a special toast, often drunk from a special horn or cup

- To family members - spouses, parents, mothers etc.

- To Georgia, the home country - if there are foreign guests, the toast is to their home countries too

Then there are also "sad" toasts in between:

- To passed away ancestors

- To recently passed away loved ones

A "sad" toast needs to be followed by a happy one (to love, children, the future, for instance) almost right away, and having a sad toast as the last one at a banquet is believed to mean bad luck. Also, guests who leave early should never leave after a sad toast. The sad toasts are thus made at the beginning of the event, and there are at normal supras just one or two sad toasts, but if it's at a funeral there will be many more of them as the deceased person's dead family members and close friends will each be toasted.

.jpg/440px-Georgian_Feast_(7).jpg) Saying the toasts is something reserved for the tamada, though after a toast, individual guests are allowed to comment on the same topic after asking the tamada to have a word. This is particularly common after the toast to the host family when individual guests thank the host for being invited. Also, if you want to leave, you should also ask for the word, say goodbye to other guests and empty your glass.

Saying the toasts is something reserved for the tamada, though after a toast, individual guests are allowed to comment on the same topic after asking the tamada to have a word. This is particularly common after the toast to the host family when individual guests thank the host for being invited. Also, if you want to leave, you should also ask for the word, say goodbye to other guests and empty your glass.

Other special toasts:

-

Alaverdi: the tamada asks a guest to say a toast, usually this is a close friend of the host or of the person which is celebrated (e.g. if the supra is to celebrate somebody's birthday). The person saying the toast needs to honor the host/person as well as possible without getting too kitschy.

-

Daschla Armaschla: at the end of a supra, the tamada says "Daschla Armaschla", meaning "the end for tonight but not the end forever". After this toast, the banquet has officially ended.

Special toasts are often drunk from special containers, like horns (hantsi) that are made from animal horn, ceramic or glass, or bowls. After emptying such a special container, they're traditionally refilled and passed on to the person next to you for the next toast. If there are no horns or bowls available, beer mugs or similar can be used.

Informal meals

Informal meals are to some extent similar to the supra; at a restaurant the host will order food for all guests, which is the placed in the middle of the table for everyone to help themselves. At restaurants it's uncommon to order just your own food, and so foreigners (solo travelers especially) may find it tricky as dishes are meant for sharing and therefore quite large. If there are many of you, follow the local practice of ordering a couple of dishes and sharing them.

At home, too, the food is placed on the middle of the table. Occasionally there may be a tamada, usually the host him/herself, in which case there will be toasts (and guests only empty their glass at a toast), but it's otherwise much less formal and scheduled than a supra.

Respect

If Georgians invite you for a meal at a restaurant or at home, expect a plentitude of food. It's impossible to eat everything up, though it would be a great embarrassment to the host if you would do so, because it would mean they have ordered or purchased too little of it. Expect that there will be a lot of food left, but don't worry about it – try a little bit of everything and enjoy the variety of the local cuisine!