A ceasefire agreement in Nagorno-Karabakh went into effect on 10 November 2020, but you should exercise extreme caution while in this region. The ceasefire agreement included moving large parts of the area back under Azerbaijani control. Many governments advise against all travel to Nagorno-Karabakh and the military occupied area surrounding it, within 5 km of the Line of Contact, and within 5 km of the border with Armenia. For more information, see war zone safety.

Nagorno-Karabakh (Armenian: Լեռնային Ղարաբաղ; Azerbaijani: Dağlıq Qarabağ) is a region in the Caucasus, officially part of Azerbaijan, but partly controlled by the unrecognized Republic of Artsakh.

Largely rural, Nagorno-Karabakh's charms lie in its historic monuments, medieval monasteries, and charismatic fauna. The region is a popular tourist destination among Armenians and members of the Armenian diaspora.

The area of the Karabakh region under Azerbaijan's control is covered in the Karabakh (Azerbaijan) section. Because it is under the control of Azerbaijan, Wikivoyage breadcrumbs it under Azerbaijan. This page does not represent a political endorsement of the claims of either side of the dispute.

Cities

- Stepanakert (Khankendi) – The capital is a small city and your likely base for exploring the region

- Martakert (Aghdara) – The administrative center of Martakert Province with the Sarsang Reservoir

- Martuni (Khojavend) – A small town near the small historically important Amaras Monastery; the city became a frontline city during the latter stages of the Nagorno-Karabakh War but also contains number of tombs from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, several ruined medieval churches and remains of settlements and khachkars.

Other destinations

- Vank – A small town close to the monastery of Gandzasar, one of Karabakh's top attractions. Also known for a hotel in the shape of a boat with a zoo, and the wall of license plates.

Understand

Political status

Politically, Nagorno-Karabakh is a part of Azerbaijan, but in the early 1990s, there was a movement to secede from Azerbaijan and join Armenia, an act which greatly angered Azerbaijan and is at the forefront of the very bitter Nagorno-Karabakh conflict that has strained Armenia-Azerbaijan relations for decades.

Although no country formally recognises Nagorno-Karabakh's independence, its de facto independence is maintained through economic and military support from Armenia. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, feels that Armenia is violating their sovereignty.

Nagorno-Karabakh was in a state of political limbo from 1994, when it declared independence, until 2020 when Azerbaijan regained much of its territory. It remains recognized as part of Azerbaijan by all UN member states and has been recognized only by three other self-proclaimed and unrecognized states: Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia.

Background

In 1920, Soviet Russia's Red Army occupied the Caucasus, leading to the formation of Armenia's and Azerbaijan's Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs). The region of Karabakh, historically linked to both Armenian and Azeri ethnic groups, quickly became hotly-contested between these SSRs. In the end, the Soviet government opted to assign the region to Azerbaijan SSR, while keeping part of it, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, as an Armenian-majority autonomous region.

By the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was in process of decline, with growing tensions between Armenia SSR and Azerbaijan SSR due to the dispute of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. After the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s, the situation finally escalated in 1992, when the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast declared itself independent from Azerbaijan, immediately getting support from Armenia. This led to a war of independence, similar to those in Transnistria and in some other ethnically mixed areas on the former Soviet empire's fringe, and the area was ethnically cleansed of its Azeri population.

The fighting stopped with the 1994 ceasefire and the dispute moved from the theatre of war to diplomatic circles (the OSCE Minsk Group), where the region is still squabbled over by Armenia and its ally Russia, and Azerbaijan and its ally Turkey.

Fighting erupted again in September-November 2020, ending with a ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia that returned control to Azerbaijan areas inside and outside of Nagorno-Karabakh that had been occupied by Armenian forces and deployed Russian troops to the remaining Armenian-controlled areas for peacekeeping duties.

Culture

During the conflict, the Azeri population was ethnically cleansed from the area. The region is culturally a part of Armenia. However there is a distinct border complete with immigration formalities on the road from Armenia. Investment and development in the region has invariably come from Armenians, further entrenching Armenian cultural ties.

Geography

Nagorno-Karabakh is a landlocked region in the South Caucasus, lying between Lower Karabakh and Zangezur and covering the southeastern range of the Lesser Caucasus mountains. It is mostly mountainous and forested.

Get in

As result of the war that started in September 2020 and culminated in the ceasefire agreement of 10 November 2020, the Nagorno-Karabakh region's political status is unclear. Some of the area is under Azerbaijani control, and the area is heavily militarised with Russian, Azerbaijani and Armenian troops. Entry for independent travellers appeared to be possible from Yerevan as of July 2021. Given the fluid state of affairs, information below may be outdated, and you will have to inquire in Yerevan.

Entry requirements

Nagorno-Karabakh can be entered only from Armenia. Doing so is considered an illegal entry into Azerbaijani territory by Azerbaijan.

Nagorno-Karabakh can be entered only from Armenia. Doing so is considered an illegal entry into Azerbaijani territory by Azerbaijan.

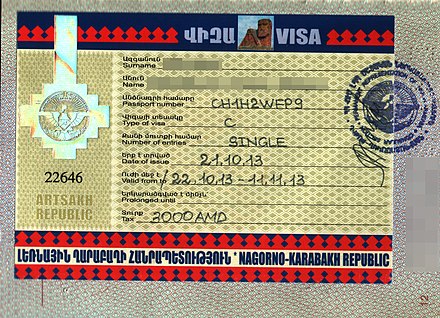

Unless you hold an Armenian (or perhaps Russian) passport, you must obtain a visa in advance (M-F 09:00 to 17:00, lunch hour from 13:00) from:

- the Permanent Mission to the Republic of Armenia (dead link: December 2020), 17A Nairi Zaryan St, Yerevan, Armenia (+374 10 24 97 05 , nkr@arminco.com)—it can take a few days for the visa to be issued. If you do not have a photo, it's not that big of a deal.

Tourist visas are free and are usually valid for 21 days after issue, but many applications are declined since the 2020 war, as applicants are also apparently screened by Russia, which has made it much more restrictive. Reapplying may or may not work. American passport holders are said to have an especially hard time getting approval.

Vehicles entering will be stopped at Russian peacekeeper checkpoints along the highway to Stepanakert. Even a visa will not ensure that you will be allowed to enter by the Russians. Register your arrival with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Azatamartikneri Street 28, Stepanakert +374 47 94 14 18 , cons@mfa.nk.am) when you arrive Stepanakert.

Because the visa will not automatically be pasted into your passport, you can use it to conceal unwanted stamps.

There are no checkpoints administrated by Armenia when entering or leaving Nagorno-Karabakh. Your original Armenian visa remains valid and is needed to continue traveling in Armenia. However, you cannot obtain a new visa when entering Armenia from Nagorno-Karabakh, so make sure your Armenian visa is valid long enough that it will not expire before you leave Armenia after re-entering the country from N-K.

By bus

There are daily bus connections between Yerevan and Stepanakert, as well as Goris and Stepanakert: see Stepanakert#Get in for more details. Buses and marshrutkas taking the southern route into Nagorno-Karabakh also pass by Shushi on their way.

By car

The main road into the region runs from Yerevan in Armenia to the region's capital Stepanakert via the Lachin Corridor, a mountain pass near the town of Lachin (Berdzor in Armenian).

By taxi

Taxi drivers in Yerevan may be willing to drive you to Stepanakert and vice versa. Expect to pay US$80–100, and be wary.

The embassy in Yerevan and also tour companies there (Artsakh in Armenian) can arrange drivers to take you to Stepanakert and to show you the region's biggest attractions. This costs about US$100–150 per person.

By plane

Stepanakert has the only airport in the region, and one airline, Artsakh Air. The conflict with Azerbaijan has prevented any planes from taking off, though. The Azeris have said that they will shoot down any flights that they don't control. As of Jan 2021 there were still no flights, but there were renewed plans to operate flights from Armenia.

Stepanakert has the only airport in the region, and one airline, Artsakh Air. The conflict with Azerbaijan has prevented any planes from taking off, though. The Azeris have said that they will shoot down any flights that they don't control. As of Jan 2021 there were still no flights, but there were renewed plans to operate flights from Armenia.

By train

The railway line between Yevlakh and Stepanakert has not been in use on the Kocharli-Stepanakert part since the First Karabakh War.

Therefore the only two railway stations on the former NKAO territory (Stepanakert and Askeran) are in ruins.

The line may reopen in the distant future.

Get around

The reconstructed Karmir Shuka-Stepanakert-Askeran-Martakert motorway runs north-south through the region and has drastically reduced travel times to just a couple hours from just about any place in the country (excluding small villages and monasteries secluded in hilly terrain).

Stepanakert has a fair number of hotels and is right on the main highway in a central location.

By bus

You can reach almost every destination from the central bus station in Stepanakert. Ask there when your bus or marshrutka starts. If you start from the central bus station your visa could be controlled. From all other bus stations there is no visa control.

By car

If you plan to travel to Karabakh from Yerevan, there are several car rental agencies in Yerevan that provide cars which can also be driven into Nagorno-Karabakh.

If your Armenian or Russian is good, you may be able to hitch a ride for less than a taxi (although don't pay too much less, as these are certainly not affluent people), and you could very easily be invited for dinner with them (in which you should have some gift, especially wine, coffee, or chocolates, and do not offer money) as the people of Nagorno-Karabakh are doing this out of hospitality.

By taxi

Taxis are available in most cities, with a new north-south road across the Nagorno-Karabakh making for a smooth and quicker (than you'd expect) ride across the region. These cost about 120 dram/km within a town, or 150 dram/km if you take the cab out of town.

By thumb

As in Armenia, hitchhiking is extremely easy. Most cars that pass will stop, and you will be offered free food and alcohol during your ride. Wait times can be long because of the lack of traffic, but once you have gotten a ride you will likely be driven for a long distance. Hitchhiking in the north of Karabakh is more difficult because of the lack of vehicles and poor road conditions, but the friendliness of the locals will help to counteract this.

On foot

All cities are small and fairly safe, so it is best to walk around the few cities in Nagorno-Karabakh. Not only will you save a little money, but you will get a good sense of the region and its people.

Talk

Armenian and Russian are widely used. Karabakh Armenians speak a dialect of Eastern Armenian that differs substantially from the Armenian spoken in Yerevan - though most Karabakh Armenians can speak the Yerevan dialect if necessary, and all can understand it. Most older Karabakhtsis can speak Azeri but it is no longer used and is becoming forgotten. Relatively few locals speak English (though those working in tourist-related areas, i.e. hotels and restaurants, often do speak a reasonable bit of English or at least can find someone who speaks the language).

See

Valuable information about tourist sites is given at the website of Karabakh's travel organisation.

Important tourist attractions inside of the main two cities include:

- Stepanakert, the capital city

- Shuka (Farmers market)

- Tatik Papik aka We Are Our Mountains (famous monument on northern outskirts)

Furthermore, many monasteries and other attractions can be found:

-

Gandzasar monastery. A main tourist attraction, literally meaning "treasure mountain". The fortified monastery has extensive carvings in the stone, beautiful architecture and sweeping views.

-

Dadivank monastery. Extensive monastery complex with red hues, a pair of covered impressive "lacework" khachkars and remnants of frescoes. It's undergoing a slow restoration and has a rich history to share.

-

Amaras monastery. A simple basilica church with surrounding serf walls. Rebuilt many times over the years, it has a very long and rich history. 2019-06-25

-

Yeghish Arakyal monastery. A somewhat simpler version of Dadivank, in the hard to access far north of Artsakh. The complex has few visitors and is overgrown with vegetation in the lush forest it is found in. 2019-06-25

-

Yerits Mankants monastery (Yeritsmankants). This beautiful remote monastery in an incredibly stunning river canyon is rarely visited, as military permission and a military escort are needed to reach this place. 2019-06-25

-

Askeran fortress (Mayraberd). 10th–18th centuries. Served as the primary bulwark against Turko-nomadic incursions from the eastern steppe. The fort is found to the northeast of the region's capital city of Stepanakert in Askeran, and once extended across the entire river valley. 2019-06-25

Do

- The website of Karabakh's travel organisation has all major events in the country is listed.

- Janapar Trail – One way to see much of Karabakh is simply to walk from one end to the other on this picturesque hiking trail. There is a marked trail which is broken up into day hikes which extend for 2 weeks of hiking. There are side trails and alternative routes as well. Trails take you to ancient monasteries and fortresses, through forests and valleys, to hot springs and villages. Each night you can either stay with a village family or camp out.

Buy

Money

Nagorno-Karabakh uses the Armenian dram (֏ or AMD) for most transactions. The state bank has also issued limited amounts of another currency, Nagorno-Karabakh dram (no symbol or ISO code). The NK dram is available in 2 & 10 dram banknotes and 50 luma (0.5 dram), 1 dram, & 5 dram coins. All banknotes & coins are dated 2004. NK dram are becoming less common, since they were printed in limited quantities, aren't worth much, and many note & coins have been taken out of the region as souvenirs or to sell to collectors. U.S. dollars & Russian rubles are accepted by some merchants, hotels and others.

The ATMs of the Karabakh's own bank named Artsakhbank (dead link: January 2023) do not accept Visa or Mastercard. All other banks accept them.

Shopping

There are several tourist/souvenir shops in Stepanakert.

The area is known for rugs, which make good souvenirs, and it is said that many people in the region and bordering countries learned rug making from the ancient Armenians of Karabakh.

Eat

- Jingalov Hats — a bread that has greens baked into it, a local specialty.

- Tutti Chamich — mulberry raisins, available at the market (shuka)

Many Mulberry trees are to be found, but make sure to eat only ripe fruit - a dark black/red or a pure white. They should not have any green, and should be plump and sweet.

Drink

Tutti Oghi — Mulberry Vodka, which Karabakh is famous for, often reaching 80% alcohol, and with a distinct taste.

The Shekher Winery produces a good quality wine.

Sleep

See the city articles for the individual options.

Also, the Janapar Trail article has an extensive range of homestays in towns and villages along the trail through Nagorno-Karabakh.

Work

Limitless volunteer work for the willing. Incredibly low cost of living. The government will gladly give most people land as long as they are willing to farm and tend to it.

Stay safe

Western governments advise their citizens to avoid the region but in spite of that, hundreds of westerners visit Nagorno-Karabakh every year.

Don't venture east of the Mardakert-Martuni highway, where the ceasefire line is located. Otherwise, it is very safe to travel around and interact with people. When you first arrive in Karabakh, you must go to what is called the "MIT", the Stepanakert foreign affairs office, to get your travel papers. This will prevent any confusion if one gets pulled over or stopped by local authorities.

If you are planning to hike, be in rural areas, or stay on the outskirts of cities note that the area is inhabited by bears and wolves. While they will not attack if unprovoked, practice bear safety and walk away slowly if unexpectedly approached. If you are planning to hike, the Janapar Trail has been broken into day-long hikes and it is best to take advantage of the homestays offered rather than to camp alongside the trails. If you do camp, make sure to keep your food high in a tree and a few dozen meters (a hundred feet or so) from your tent and do not simply sleep on the ground or in a sleeping bag. Sleep inside a tent.

While the region is fairly safe in terms of crime, you must not lose your passport. There are no foreign embassies in the Nagorno-Karabakh, and you may have a hard time leaving Nagorno-Karabakh without a passport or visa. The US embassy in Baku says that "because of the existing state of hostilities, consular services are not available to Americans in Nagorno-Karabakh." It would be safe to assume that this applies to all other nationalities and their embassies in Baku.

Stay healthy

Drink bottled water if you are not accustomed to the local water. However if you are hiking, drinking water in mountain streams and ponds in reasonably safe, as long as you are sure it is not downstream from a large town (in which case it is likely contaminated with chemicals, street runoff, and/or waste.

This is a rural region: in the event of a medical emergency the hospitals in Nagorno-Karabakh are no more than a modest clinic. The nearest major hospital is in Yerevan, a long distance in the event of a heart attack or complications with any medical problems you may have. It is best to have with you a small first aid kit with bandaids, bandages, anti-biotic cream, ibuprofen, and any other medicine you may need.

Respect

The wiki on the Janapar trail recommends no trace camping and if you bathe, make sure no locals are around (it may be offensive). Just as stated above, you will receive offers of food and rest. Have gifts for such people, but do not offer money.

Connect

It is recommended to have a SIM card of the company Vivacell. All other phone operators that are active in this region refuse for political reasons roaming inside Karabakh.

Alternatively get a SIM card from Karabakh's own phone company Karabakh Telecom when you are in Stepanakert. All you need is your passport and 1,200 dram. This includes the cost for the SIM card and 600 dram as initial money in your account. Using mobile Internet is also possible. The Karabakh Telecom's main office in the Vardan Mamikonyan St. 23 in Stepanakert has personnel speaking English. They can also help you if you have technical problems with your phone.