Purnululu National Park - national park in the Kimberley region of Western Australia

Purnululu National Park is a world heritage site in Western Australia, 2054 km northeast of Perth. The nearest town is Kununurra which is a good 300 kilometres away, making this park pretty isolated, even more so than Uluru. Interestingly, before 1983, the Bungle Bungle Range had not been known to outsiders, although the Indigenous Karjaganujaru peoples have lived in this park for over 40,000 years.

Understand

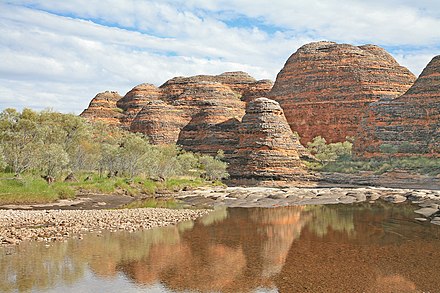

Purnululu is the name given to the sandstone area of the Bungle Bungle Range by the Kija Aboriginal people, and the national park is also known as the Bungles National Park. The range is situated within the park, rises up to 578 m (1896 feet) above sea level and is famous for the unusual and striking sandstone domes striped with alternating orange and grey bands. The banding of the domes is due to differences in clay content and porosity of the sandstone layers. The grey banding is cyanobacteria which grows on the layers where moisture accumulates. The orange bands are layers of oxidised iron compounds that dry out too quickly for the cyanobacteria to form.

Purnululu is the name given to the sandstone area of the Bungle Bungle Range by the Kija Aboriginal people, and the national park is also known as the Bungles National Park. The range is situated within the park, rises up to 578 m (1896 feet) above sea level and is famous for the unusual and striking sandstone domes striped with alternating orange and grey bands. The banding of the domes is due to differences in clay content and porosity of the sandstone layers. The grey banding is cyanobacteria which grows on the layers where moisture accumulates. The orange bands are layers of oxidised iron compounds that dry out too quickly for the cyanobacteria to form.

History

The term Purnululu National Park is actually quite a new one. Apart from the indigenous people, no one had known about the Bungle Bungle ranges until the 1980s, which is fairly recent as to land discovery. However, nevertheless to say, the area does have a rich indigenous history with several Aboriginal art and burial sites are numerous in this area.

The name "Purnululu" means sandstone in the language of the local Kija tribe. It is believed that it was either misinterpreted as "Bungle Bungle" or that it is a misspelling of the common Kimberley Grass Bundle. However, rumors still circulate as to the real origin and meaning of Bungle Bungle, making this "lost world" seem even more mysterious.

The park became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

Landscape

The Bungle Bungle Range is one of the most extensive and impressive occurrences of sandstone tower (or cone) karst terrain in the world. The Bungle Bungles were a plateau of Devonian sandstone, carved into a mass of beehive-shaped towers with regularly alternating, dark grey bands of cyanobacterial crust (single cell photosynthetic organisms). The plateau is dissected by 100–200-metre (330–660 ft) deep, sheer-sided gorges and slot canyons. The cone-towers are steep-sided, with an abrupt break of slope at the base and have domed summits. How they were formed is not yet completely understood. Their surface is fragile but stabilised by crusts of iron oxide and bacteria. They provide an outstanding example of land formation by dissolutional weathering of sandstone, with removal of sand grains by wind, rain and sheet wash on slopes.

Flora and fauna

The plateau and domes themselves are devoid of vegetation, but there are islands of green with more than 600 documented plant species both between the beehives and at the gorge entrances. Some of the plants in the park don't even have a name yet, as they were only recently discovered.

The fan palm (Livistona victoriae) is particularly eye-catching; it clings to walls and crevices in dangerously steep places, especially in the northwest, and reaches heights of up to twelve metres. Tree species that cling to rocks with their roots include the rock fig, the milkwood tree and the dwarf tropical red box gum.

Much of the park consists of undulating, deep red or yellow sandy plains overgrown with acacia and silver tree bushes, eucalyptus forests, spinifex and other grasses. Kapok bushes, Kimberley bauhinia, Kimberley heather and Grevillea species mix up the savannah with colour.

When it comes to fauna, the biodiversity in the park is remarkable; particularly related to the boundary between the tropical and arid climate zones, which ensures that species from both climate zones coexist. Over 40 species of mammals and over 80 species of reptiles are documented in the park.

For example, the flat-toed kangaroo comes from tropical latitudes, while the mountain kangaroo comes from stony dry zones. The frilled lizard is native to the north, the brown snake is adapted to both wet and dry habitats.

The animals that are the easiest to spot in the park are the birds. There are around 150 species, including spinifex pigeons and flocks of brightly coloured budgerigars. Other species such as the nocturnal swallowtail, white- tipped pigeon, and brown-breasted fathead are so well camouflaged that they barely stand out against the rocks they inhabit.

Climate

Visitor information

- Purnululu Information Bay, Spring Creek just off the Great Northern Highway turnoff, -17.4324°, 127.995°. This information bay is the last point of information before doing a long drive into the park. Has picnic tables and a toilet, plus a bay for important updates. This is on top of the visitor centre. 2021-12-04

- Purnululu Visitor Centre, -17.4208°, 128.299°. 8AM-noon and 1-4PM from April until 1 October. Has information on its recreation and the local and cultural heritage of this place. The visitor centre also sells cold drinks, ice, snacks and souvenirs. 2021-12-04

Get in

Access to the park by road is via Spring Creek Track from the Great Northern Highway approximately 250 km south of Kununurra. The track is 53 km (33 miles) long and is only passable in the dry season for 4WD vehicles. It will take approximately 3 hours to negotiate that distance to the visitor centre. Access by air is less painful and helicopter flights are available from Turkey Creek Roadhouse (Warmun), 187 km south of Kununurra, or by light aircraft from Kununurra.

During the monsoon season (from November and April 1) or the summer months, it is not possible to enter the park and the park is closed during then.

Fees and permits

The Bungle Bungle section of the park has a fee, although the fees tend to get a little bit complicated. Up to date fee info can be found on the park's website.

- For a private vehicle with up to 12 people, it's $15 per vehicle, but the concession fee is $8

- For a private vehicle with more than 12 people, $7 per occupant who 6 years or older. The concession fee is $2.50 per occupant

- If you come by motorcycle, it's just $8

Get around

All the roads in Purnululu National Park past the caravan park are unpaved so you will need a 4WD to get around most of the time.

See

Budgerigars, wallabies, bungle bungle range, gorges, rock pools, sandstone towers and fan palm trees in crevices in rocks.

Budgerigars, wallabies, bungle bungle range, gorges, rock pools, sandstone towers and fan palm trees in crevices in rocks.

- Kungkalanayi Lookout, Ord River, -17.4163°, 128.306°. This lookout provides panoramic 360° views of the spectacular Bungle Bungle range, and it holds a secret surprise at sunset. It's also one of the most visited lookouts as well. 2021-09-22

- Echidna Chasm, -17.328725°, 128.415497°. A 180m deep chasm that glows when the sunlight comes overhead, usually between the hours of 11AM and 1PM. Walking here is a 2 kilometre return walk. 2021-12-04

- Osmand Lookout, -17.322186°, 128.416778°. A lookout that's one of a kind giving you views of the Osmand Range with some panoramic views. Getting here is also only a short 1 kilometre walk as well. 2021-12-04

Do

- Scenic Helicopter Flights, Bellburn Airstrip, -17.543786°, 128.307439°, +61 8 9168 7335. There are helicopter tours from Bellburn Airstrip allowing better views of the 360 million year rock formation, offered by HeliSpirit. Parks WA website. 2021-09-22

Buy

The only shop of any kind in the park is at the visitor centre.

Eat and drink

- The visitor centre sells snacks and other quick eateries, however, they tend to be very very expensive given how isolated Purnululu National Park is.

- Bungle Bungle Savannah Lodge has dinner and breakfast as well as a fully licensed bar

Sleep

Lodging

- Bungle Bungle Savannah Lodge, -17.532114°, 128.292818°, +61 8 9168 2213. Check-in: 3PM, check-out: 10AM. Eco lodging near the Bungle Bungle Ranges. Facilities include a pool, a licensed bar, and dinner and breakfast facilities. 2022-01-16

- Bungle Bungle Wilderness Lodge, -17.565125°, 128.420169°, +61 1300 336 932. Check-in: 3PM, check-out: 10AM. An ecofriendly lodge with dinner and breakfast included. The lodge also has tea, coffee, filtered water and packed lunches available. 2022-01-16

Camping

There are two public campgrounds in the park - Walardi to the south, near Cathedral Gorge and Picaninny Creek, and Kurrajong to the north near Echidna Chasm. They are basic campgrounds which offer water, shared fireplaces with a limited supply of wood provided (no collecting because it's a national park) and pit toilets. Booking ahead is advisable since you don't want to be turned back after the long drive in from the highway.

- Walardi campground, -17.5216°, 128.301°. $13 per adult, $10 per concession card holder, $3 per child per night 2022-01-17

- Kurrajong campground, -17.3872°, 128.33°. A large campground which contains 106 campsites. It's a seven kilometre journey to the visitor centre, and known for being near a sunset spot. $13 per adult, $10 per concession card holder, $3 per child per night 2022-01-26

Backcountry

Backcountry camping is generally not advised due to safety concerns and is prohibited in large parts of the park.

Nearby

- Bungle Bungle Caravan Park (Bungle Bungle Expeditions), Turn off the Great Northern Highway toward Purnululu Nat Park 1km (1km along the Purnululu National Park access track - accessible to all vehicles.), -17.43643°, 127.99816°, info@bunglebunglecaravanpark.com.au. This Station Stay Caravan Park was established on Mabel Downs Station in 2010. Facilities are "bush" style and basic but has a great atmosphere. Meals available. For those that don't wish to brave the long rough track into the National Park a full day 4wd Bus tour leaves from here May to October. Caravan sites $35 Luxury Safari Tents $120

Stay safe

Go next

- Piccanninny Creek

- Ord River

- Panton River

Purnululu National Park

parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park/purnululuWestern Australia

Primary administrative division