Syria - sovereign state in western Asia

Many governments advise against all travel to Syria due to the ongoing civil war. Although most of the country has been reclaimed by the government, the political situation is still unstable, and Idlib province remains a stronghold of Al-Qaeda and Al-Nusra. Terrorist attacks, kidnapping and fighting between rival armies are common. Consular services are generally not available.

On February 6, 2023, strong earthquakes struck Northwestern Syria, causing widespread damage and casualties, especially in areas near the border with Turkey. Travel within as well as into these regions is difficult and strongly discouraged.

Aftershocks are frequent, and you should seek secure shelter when they strike. See earthquake safety for more information on surviving an earthquake.

Syria (الجمهوريّة العربيّة السّوريّة Al-Jumhuriya al-`Arabiya as-Suriya, the Syrian Arab Republic) is a country in the Middle East. Rich in history, the capital, Damascus, is the world's oldest continuously inhabited city, and the country has been the site of numerous empires.

Since 2011, the country has been torn apart by a brutal civil war. This aside, the country offers numerous attractions and some daring travellers have been able to visit Syria without hesitation.

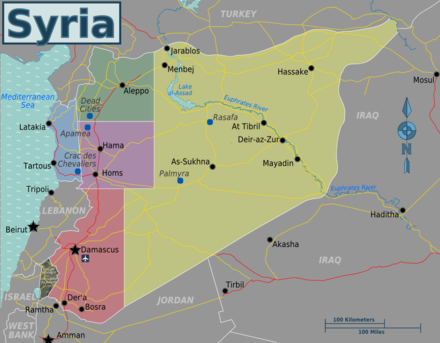

Regions

Syria has 14 governorates, but the following conceptual division used to make more sense for travelers:

Aleppo, one of the oldest cities in the world, as well as the Dead Cities, 700 abandoned settlements in the northwest of the country

A volcanic plateau in the southwest of Syria, also includes the capital Damascus and its sphere of influence

The Orontes Valley, home to the towns of Hama and Homs

Green and fertile, relatively Christian, somewhat liberal, and dominated by Phoenician and Crusader history. Also serves as the country's main access point to the sea.

A vast sparsely populated desert with the oasis of Palmyra, as well the basin of the Euphrates, which is associated with the Assyrian and Babylonian history

Other destinations

- Apamea — a former Roman city that once housed about half a million people. Apamea was hit by an earthquake in the 12th century and much of it was destroyed but it still boasts a long street lined with columns, some of which have twisted fluting.

- Bosra — a Roman city in southern Syria close to the Jordan border noted for the use of black basalt stones and its well preserved theatre

- Dead Cities — a series of towns that once formed part of Antioch. They have long since been abandoned but make an interesting stop for tourists. Al Bara boasts pyramidal tombs and formerly grand archways set on modern farm land. Serjilla is another famous dead city.

- Der Mar Musa — not a tourist site, but an active Christian monastery actively promoting Islamic/Christian dialogue. Welcomes Christians and followers of other religious traditions. It is 80 km north of Damascus.

- Krak des Chevaliers — the archetypal Crusader castle, magnificently preserved and not to be missed

- Palmyra — formerly held the once-magnificent ruins of a Roman city, in the middle of the desert. Once considered the main attraction in Syria, the UNESCO-listed heritage site was severely damaged by Daesh extremists in 2015. Restoration and de-mining is underway as of 2019.

- Saladin's Castle — a quiet gem in a valley with pine trees about 37 km inland from Latakia

- Salamieh — Salamieh is an ancient city which was first known during Babylonian times in 3500 BC; contains Shmemis castle, Greek temple of Zeus, the old hammam, the old walls, remains of Roman canals

Understand

Syria's population has fallen from 21.9 million people in 2009 to 18.3 million in 2017 (UN estimates). About 4½ million are concentrated in the Damascus governorate. A moderately large country (185,180 km<sup>2</sup> or 72,150 sq miles), Syria is situated centrally within the Middle East region and has land borders with Turkey in the north, with Israel and Lebanon in the south, and with Iraq and Jordan in the east and south-east respectively.

Syria's population has fallen from 21.9 million people in 2009 to 18.3 million in 2017 (UN estimates). About 4½ million are concentrated in the Damascus governorate. A moderately large country (185,180 km<sup>2</sup> or 72,150 sq miles), Syria is situated centrally within the Middle East region and has land borders with Turkey in the north, with Israel and Lebanon in the south, and with Iraq and Jordan in the east and south-east respectively.

The population of Syria is predominantly Arab (90%), with significant minorities of other ethnic groups: Kurds, Armenians, Circassians, and Turks. The official language is Arabic, but other tongues that are occasionally understood include Kurdish, Armenian, Turkish, French, and English. The Syrian Republic is officially secular. Nonetheless, it is greatly influenced by the majority religion of Islam (80% of the population, split between 64% Sunni Muslim and 16% other Muslim, Alawite, and Druze). There is a significant Christian minority that amounts to about 10% of the population.

The President of Syria is Bashar al-Assad, who replaced his father, Hafez al-Assad, soon after his death on 10 June 2000. Having studied to become an ophthalmologist (eye doctor) in Damascus and London, Bashar was groomed for the presidency after the 1994 car accident of his elder brother Basil. Consequently, he joined the army and became a colonel in 1999. Bashar's modernizing credentials were somewhat boosted by his role in a domestic anti-corruption drive, and he began his rule with increased openness. Bashar's position as head of the Syrian state rests on his presidency of the Ba'ath Party and his role as commander-in-chief of the army.

Assad's regime and the Ba'ath Party own or control most of Syria's media. Criticism of the president and his family is not permitted, and the press (both foreign and domestic) is heavily censored for material deemed threatening or embarrassing to the government. A brief period of relative press freedom arose after Bashar became president in 2000 and saw the licensing of the first private publications in almost 40 years. A later crackdown, however, imposed various restrictions regarding licensing and content. In a more relaxed manner (perhaps since these matters are largely beyond possible government control), many Syrians have gained access to foreign television broadcasts (usually via satellite) and the three state-run networks. In 2002 the government set out conditions for licensing private, commercial FM radio stations, ruling simultaneously that radio stations could not broadcast news or political content.

Syria has been in a state of civil war since 2011, which was part of the Arab spring that attempted to topple authoritarian leaders across the Arab world and transform the Arab countries into liberal democracies. Since then, numerous armed rebel groups backed by the United States and its allies have been waging a war against Assad's government, and many parts of the country remain outside government control. Russian intervention on Assad's side since 2015 has brought more than half the country back under government control, though this has been criticized by the United States and its allies as anti-democratic.

Tourist Information Offices; Damascus: 2323953, Damascus Int'l Airport: 2248473, Aleppo: 2121228, Daraa (Jordanian-Syrian border gate): 239023, Latakia: 216924, Palmyra (Tadmur): 910636, Deir-az-Zur: 358990

Get in

Entry requirements

Visas are needed for most individual travelers. These are available in 6-month (single/multiple entries), 3-month (single), and 15-day (land borders only) versions. Citizens of Arab countries do not require a visa, except unaccompanied Moroccan women below 40 years old. In addition, Malaysian, Turkish, and Iranian citizens do not require visas.

Getting visas in advance is expensive and confusing. Americans are required to apply in advance at the Syrian embassy in Washington DC, even if they live elsewhere, and pay US$131 or €100. Most other travelers, though, can get them anywhere, a popular choice being Istanbul (Turkey), where they are generally issued within one day for €20 (Canadian citizens) or €30 (EU citizens). A "letter of recommendation" stating that your consulate has "no objection" to your visit to Syria may be required. The visa issued must have two stamps and a signature. Otherwise, the visa is considered invalid, and you will be turned back at the border. It is necessary to keep the blue arrival form, as travelers must submit it upon departure.

Official policy says that if your country has a Syrian embassy or consulate, you should apply for your visa in advance. Most nationals must apply for a Syrian visa in the country where they are a citizen. Alternatively, a foreign national may apply for a Syrian visa from a Syrian Consulate in a country other than their own if they hold a residency visa valid for at least six months for the country in which they are applying. There are very few exceptions to this rule. In practice, it is possible to obtain a visa at the border for most nationals.

By land

Every national can get a visa at the border, regardless of whether it is not officially written or recommended. But do not buy a bus ticket to take you across the border. They will always leave you there because it takes 2-10 hours for US citizens, and they will not tell you that in advance when purchasing the bus ticket. Buy a ticket to the border via minibus/shared taxi (servees), then do the same when you get to the other side. US citizens cost US$16 or €12, while others are more costly. Japanese are US$12-14 or €9-11, Singaporeans are US$33 or €25, Australians/New Zealanders are about US$100 or €75.99, and Swiss are US$63 or €47.88. They only take US dollars or euros. You may only receive a 15-day single-entry tourist visa and must go through this process if you ever re-enter Syria. When you exit Syria, you will have to buy/pay an exit card for about US$12 or €9.15.

Every national can get a visa at the border, regardless of whether it is not officially written or recommended. But do not buy a bus ticket to take you across the border. They will always leave you there because it takes 2-10 hours for US citizens, and they will not tell you that in advance when purchasing the bus ticket. Buy a ticket to the border via minibus/shared taxi (servees), then do the same when you get to the other side. US citizens cost US$16 or €12, while others are more costly. Japanese are US$12-14 or €9-11, Singaporeans are US$33 or €25, Australians/New Zealanders are about US$100 or €75.99, and Swiss are US$63 or €47.88. They only take US dollars or euros. You may only receive a 15-day single-entry tourist visa and must go through this process if you ever re-enter Syria. When you exit Syria, you will have to buy/pay an exit card for about US$12 or €9.15.

If going by land and you are planning to get a visa on the border, bring US dollars, euros, or Syrian pounds. Other foreign currencies will not get a reasonable exchange rate, and there are no credit/debit card facilities at most crossings. Traveler's checks are also not accepted.

American citizens need to beware of sanctions on Syria. While traveling and spending money in Syria is permitted, you may not fly with Syrian Arab Airlines. More importantly, many US banks err on the safe side and ban all business with Syria. Some credit or ATM cards may not work, although many Americans today experience little problems. Be wary, however, as some travelers have had their bank account access frozen, regardless of whether or not they informed their bank of travel to Syria.

Due to the conflict, various areas of Syria are not under the control of the Syrian central government. Areas near Turkey are under the control of Kurdish and rebel forces. Foreigners will not be allowed to cross these borders, and Turkey/Syria borders are generally closed now because of the conflict. From the Kurdish Region of Iraq, people cross over the river into Syria at Faith Khabour. However, the crossing is only for humanitarian workers, and non-aid workers may not be allowed to travel.

By plane

_AN2190526.jpg/440px-Damascus_-_International_(DAM_-_OSDI)_AN2190526.jpg) Syria has two functioning international airports: Damascus International Airport (IATA: DAM), 35 km (22 miles) southeast of the capital and Bassel al-Assad International Airport (IATA: LTK), south of Latakia, the main sea port of the country. Due to the ongoing civil war, most airlines have suspended service to these airports. As of 2018, Damascus International Airport is operational, though there are just a dozen of departures daily.

Syria has two functioning international airports: Damascus International Airport (IATA: DAM), 35 km (22 miles) southeast of the capital and Bassel al-Assad International Airport (IATA: LTK), south of Latakia, the main sea port of the country. Due to the ongoing civil war, most airlines have suspended service to these airports. As of 2018, Damascus International Airport is operational, though there are just a dozen of departures daily.

Upon arrival, a free entry visa can be delivered to almost all travellers if they are being received by a local travel agency. Call the Syrian Embassy in your home country for more information.

Syria levies a departure tax (~US$13) at land and sea borders. Airport departure tax is included in the ticket price, and airlines will put a manual stamp on your boarding pass.

One of the practical and reasonable ways to enter Syria from Turkey is to take a domestic flight to Gaziantep and then taxi to Aleppo through Oncupinar border-gate in Kilis. The journey takes around 2 hours including custom formalities. The fare is US$60, per car with max 4 and one way. Taxis holding licence can be arranged in Kilis or Gaziantep. Turkcan Turizm, 0348 822 3313

By train

As of 2020, all international and most domestic trains have been suspended indefinitely. Former international routes included the historical Toros Express from Istanbul to Aleppo and an overnight train from Tehran to Damascus.

By bus

Buses run from Turkey, with frequent connections from Antakya (Hatay). You can also travel by bus from Jordan & Lebanon. Buses to Damascus run from Beirut.

When arriving in Damascus by bus, move away from the bus terminal to find a taxi to the town center. Otherwise, you risk paying several times the going rate, as cars posing as taxis operate next to the terminal.

This is usually a two-person operation, with one person trying to distract you while the driver puts your suitcase into the trunk of the "taxi" and locks it.

By car

When traveling from Lebanon, service taxis (which follow a fixed route only, usually from one bus station to another) are a convenient way to reach Damascus, Homs, Tartus, Aleppo, or other Syrian towns. A shared service taxi from Beirut to Damascus will cost about US$17 per person, based on four people sharing the same taxi. You will have to pay for every seat if you want a private taxi. In most cases, buying a Syrian visa before leaving home is necessary, often costing about US$130 or less, depending on the country of residency. It's possible to obtain a free entry visa for tourists if being received by a local Travel Agency. It is also possible to arrive by car from Turkey. A private taxi from Gaziantep Airport (Turkey) will cost about US$60.

Service taxis run from Daraa across the Jordanian border to Ramtha; from there, microbuses are available to Irbid and Amman -- the stop in Daraa permits a side trip to Bosra, with UNESCO-recognised Roman theater and ruins.

By boat

- The nearest car ferry port is Bodrum in Turkey.

- Occasional passenger ferries run between Latakia and Limassol, Cyprus. This service has come and gone over the years. Confirm that the departure will occur with Varianos Travel before making plans to incorporate this route.

- Latakia and Tartous serve as ports of call for several Mediterranean cruise lines.

Get around

By taxi

The taxis (usually yellow, always clearly marked) quickly get around Damascus, Aleppo, and other cities. Arabic would be helpful: most taxi drivers do not speak English. All licensed taxis carry meters, and it is best to insist that the driver put the meter on and watch it stay on. Most drivers expect to haggle prices with foreign travelers rather than use the meter. Private cab services (which advertise prominently at the airport) charge substantially more.

However, there is also a bus from Baramkeh station to the airport.

By car

Visitors can rent cars at various Sixt, Budget, and Europcar locations. Cham Tours (formerly Hertz) has an office next to the Cham Palace Hotel, which offers competitive rates starting at about US$50 per day, including tax, insurance, and unlimited kilometers.

Visitors can rent cars at various Sixt, Budget, and Europcar locations. Cham Tours (formerly Hertz) has an office next to the Cham Palace Hotel, which offers competitive rates starting at about US$50 per day, including tax, insurance, and unlimited kilometers.

Sixt Rent a Car at the Four Seasons Hotel has rates starting from US$40 per day (all-inclusive).

If you have never driven in Syria before, take a taxi first to get a first-hand idea of what traffic is like. Especially in Damascus and Aleppo, near-constant congestion, a very aggressive driving style, bad roads, and highly dubious quality of road signs make driving there an exciting experience, so err on the side of caution when traveling.

The only road rule that might come in handy is that, as opposed to most of the rest of the world, in roundabouts, the entering cars have the right of way, and the vehicles already in the roundabout have to wait. Aside from that, motorists are pretty free to do as they please.

If you have an accident in a rental car, you must obtain a police report, no matter how small the damage or clear it is who is at fault – otherwise, you will be liable for the damage. Police (road police No:115) probably will only be able to speak Arabic, so try to make other drivers help you and call your rental agency.

Gasoline/petrol (marked as "Super," red stands) costs about double diesel (green stand). Suppose you run out of fuel (try to avoid it), which is relatively easy wherever the eastern Damascus-Aleppo highway or mountains western from it, you can find some locals willing to sell you a few liters from a canister. Remember that prices may be high. Usually, gas stations are only in bigger towns and major crossroads in the desert, so try to refuel whenever you can.

By microbus

The microbuses (locally called servees or meecro) are little white vans carrying ten passengers around cities on set routes. The destinations are written on the front of the microbus in Arabic. Usually, the passenger sitting behind the driver deals with the money. You can ask the driver to stop anywhere along his route.

Often, microbuses will do longer routes, for example, to surrounding villages around Damascus and Aleppo or from Homs to Tadmor or Krak des Chevaliers. They are often more uncomfortable and crowded than the larger buses, but cheaper. Especially for shorter distances, they usually have more frequent departures than buses.

By bus or coach

Air-conditioned coaches are one of the easy ways to make longer hauls around Syria, for example, the trip from Damascus to Palmyra. Coaches are a cheap, fast and reliable way to get around the country; however, when they exist, the schedules are not to be trusted. For the busy routes, it's best to go to the coach station when you want to leave and catch the next coach, you'll have to wait a bit, but most of the time, it's less of a chore than finding out when the best coach will be leaving, and then often finding it's late.

By train

As of early 2020, rail transport in Syria is limited to a twice-daily service between the coastal cities of Latakia and Tartous and a commuter service in Aleppo. All long-distance services connected to Damascus, Aleppo, Deir-az-Zur, Al-Hassakeh, Al-Qamishli, and many other cities are canceled indefinitely. Rehabilitation is, however, underway in some sections.

The summer-only excursion steam train in Damascus, which travels to Al-Zabadani in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains and back, resumed operation in 2017. The train is popular with locals trying to escape the summer heat.

By bicycle

While traveling by bicycle may not be for everyone, and Syria is by no means a cycle tourist's paradise, there are definite advantages. Syria is a good size for cycling, and accommodation is frequent enough that even a budget traveler can get away with "credit card" touring (though in the case of Syria, it might be better to refer to it as fat-wad-of-cash touring). There are sites one can not get to with public transportation, like the Dead Cities, and the people are amiable, often inviting a tired cyclist for a break, cup of tea, meal, or night's accommodation. The problem of children throwing stones at cyclists or running behind the bicycle begging for candy and pens (such as in parts of Morocco) does not seem to have appeared in Syria. Locals, young and old alike, will be inquisitive about your travels and your bicycle, and if you stop in a town, you can expect a large crowd to gather for friendly banter about where you are from and your trip.

Wild camping is relatively easy in Syria. The biggest challenge is not finding a place for your tent but picking a spot where locals will not wander by and try to convince you to return to their home. Olive groves and other orchards can make a good spot for your tent, except on a rainy day when the mud will make life difficult. Another option is to ask to pitch your tent in a private garden or beside an official post like a police station. You will unlikely be refused as long as you can get your message across. A letter in Arabic explaining your trip will help with communication.

Syria's standard of driving skills is inadequate, and other road users tend to drive very aggressively. They seem used to seeing slow-moving traffic and usually give plenty of room as they pass. Motorcycles are the most significant danger as their drivers like to pull up alongside cyclists to chat or fly by your bike to look at the strange traveler and then perform a U-turn in the middle of the road to return home. The safest option, in this case, is to stop, talk for a few minutes and then carry on.

Finding good maps tends to be another problem. You should bring a map with you as good maps are hard to find in Syria. Free ones are available from the tourist bureaus but could be better for cycle touring. Even foreign-produced maps can contain errors or roads that don't exist, making excursions from the main route challenging. When you come to a crossroads, asking several locals for the right road is a good idea. With good maps, it can be easy to avoid riding on the main highway, which, while safe enough (a good wide shoulder exists on almost all the highways), is not very pleasant due to the smokey trucks and uninteresting scenery.

You should think about bringing a water filter or water treatment tablets with you. Bottled water is only sometimes available in smaller towns. Finding local water is easy. Tall metal water coolers in many town centers dispense free local water, always available near mosques. The Syrian word for water is pronounced like the English word “my” (as in “that is my pen”) with a slight A afterward, and if you ask at any shop or home for water, they will happily refill your bottles.

Talk

Arabic is the official language. It is always a good idea to know some words ("hello," "thank you," etc.). A surprising number of people speak at least (very) rudimentary English. Learning basic numbers in Arabic to negotiate taxi fares would be worth your while. Personnel working with foreign tourists (like tourist hotels, restaurants, tour guides, etc.) generally communicate reasonably well in English.

Due to the general lack of ability by the public to communicate in English beyond basic phrases, Syria is a great place to force yourself to learn Arabic through immersion, should you wish to improve your Arabic skill.

See

- Ancient cities such as Damascus, Aleppo, Palmyra, Crac des Chevaliers and Bosra including Medieval souqs.

- In Hama there are the Al Aasi Water Wheels in a river (نواعير نهر العاصي).

- Al Hosn Castle in Homs.

- Qala'at Samaan (Basilica of St Simeon Stylites) about 30 km (19 mi) northwest of Aleppo and the oldest surviving Byzantine church, dating back to the 5th century. This church is popularly known as either Qalaat Semaan (Arabic: قلعة سمعان Qalʿat Simʿān), the 'Fortress of Simeon', or Deir Semaan (Arabic: دير سمعان Dayr Simʿān), the 'Monastery of Simeon' .

- Tartous with its Crusader-era Templar fortress

- The Yarmouk Valley

- Endless desert and countryside in much of the country

- Mountain ranges in the west of the country

Do

- Take a scenic tour. Travel from Latakia (beach), Syrian Coast and Mountains (Safita tower, Mashta hikes and cave)

Marmarita: Virgin Mary memorial, St George Monastery, Crac des Chevaliers, Palmyra (ruins), to Damascus (souq, mosques). - Hike. in the Syrian Coast and Mountains region.

- Geocaching. Find geocaches in the area.

Buy

Money

Syria's currency unit is the Syrian pound or 'lira.' You will see a variety of notations used locally: £S, LS or S£, Arabic: الليرة السورية al-līra as-sūriyya, but Wikivoyage uses the ISO currency code SYP immediately prefixing the amount in our guides. The pound's subdivision 'piastre' is obsolete.

The black market rate for U.S. dollars is volatile. Hard currencies such as U.S. dollars, pounds sterling, or euro can not be bought legally; the black market is the only source of foreign currencies available to Syrian businessmen, students, and the very many who wish to escape abroad. The maximum foreign currency amount that can be exported legally is a remarkably generous US$3,000 equivalent per year for each traveler. Any amount over US$3,000 risks confiscation by the authorities and time in jail. There are restrictions on the export of Syrian currency of a maximum of SYP2,500 per person.

Because of high inflation and political instability, amounts expressed in Syrian pounds in these guides are subject to significant change.

Due to international sanctions, some foreign financial institutions have suspended transactions with Syria, including MasterCard and Visa, and bank cards operating under the Cirrus, Maestro, and Plus transaction networks. It is nearly impossible to change travelers' checks in Syria.

Shopping

An international student card reduces the entry fees to many tourist sites to 10% of the regular price if you are younger than 26 years. Depending on who is checking your card, you can get the reduction when you are older than 26 or have only an expired card. It is possible to buy an international student card in Syria (around US$15). Ask around discreetly.

In the souks (especially the Al-Hamidiyah Souq in the Old City of Damascus, where you can easily "get lost" for a whole morning or afternoon without getting bored), the best buys are the "nargileh" waterpipes, Koran, beautifully lacquered boxes and chess/draughts sets and (particularly in Aleppo) olive soap and traditional sweets. The quality of handicrafts varies widely, so when buying lacquered/inlaid boxes, run your hand over the surface to see that it is smooth and check, in particular, the hinges. In the souq, haggling is expected. Bargain ruthlessly.

Syrian traders who price goods in foreign currencies now face up to 10 years in jail after a decree issued by President Bashar al-Assad forbids the use of anything other than the Syrian pound as payment for any commercial transaction or cash settlement. This was because of the increasing "dollarisation" of an economy in ruins after two years of civil war.

Eat

You may also order a salad of Fatoush with your soup. Chopped tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, and herbs are mixed in a dressing and finished with a sprinkling of fried bread resembling croutons. Cheese may also be grated on top.

Drink

Fresh fruit juices are available from street stalls in most towns, such as mixed juice (usually banana, orange juice, and a few exotic fruits like pomegranate).

Beer is cheap. Syrian wine can be found, and Lebanese and French wines are also available in a higher price bracket.

Tea is served in a little glass without milk, sweetened with sugar. Add the sugar yourself, as the Syrians have a collective sweet tooth and will heap it in.

Sleep

A double room in a three stars hotel costs about US$50, US$80 for four stars, and can reach US$250 in a five-star hotel.

Learn

Before the war, Syria became a significant destination for studying Arabic, with several language schools operating in Damascus.

Work

If you enter the country on a tourist visa, don't try to work and earn money. Foreign workers should always get official approval to work. Despite this, many international students supplement their income by teaching, and many institutes in Damascus will happily hire foreigners and pay them under the table.

Stay safe

Syria has been a war zone for the last decade. Until the civil war ends, and probably for some time after that, Syria is not a place to travel to voluntarily — and you will probably not be able to buy a ticket there. Suppose you're going there on official business. In that case, your employer will most likely take care of your transportation and safety and provide up-to-date information about the places you'll be going to. However, you may find our war zone safety article helpful. The below information concerning safety may or may not apply any longer.

Travelers should avoid all large gatherings as they may turn violent. Political groups have targeted foreign travelers, especially in the country's south.

You could find yourself in trouble if you engage in open criticism of and against the Syrian government or the president. Your best bet is to avoid political conversations altogether to avoid any possible problems. If you engage in political discussions with Syrians, be aware that they might face intense questioning by the secret police (mukhabarat) if you are overheard. As a general rule, always assume that plain-clothes police officers are watching you. You will notice that not many uniformed police officers can be seen in the streets, but this is because the police have a vast network of plain clothes officers and informants.

Since begging is common in some parts of Syria, particularly outside tourist attractions, mosques, and churches, it has been known that beggars occasionally demand money and may follow you around until you give. Some have even been known to "attack" tourists just for money and food. It is advised to wear appropriate Arab clothing and try to blend in. Keeping your money in your front pockets and safe with you is also better. Beware of these scams by beggars has also led many foreign tourists to lose quite a bit of money.

Drugs

The death penalty is enforced for drug trafficking or cultivation.

Women

Women traveling alone may find that they draw a little too much attention from Syrian men. However, this is generally limited to stares or feeble attempts at conversation. If it goes beyond that, the best approach is to remain polite but be clear that approaches are unwelcome. Be loud and involve bystanders; they will often be very chivalrous and helpful.

Women can be arrested under suspicion of immoral behavior (e.g., being alone in a room with a man who is not the woman’s husband or being in a residence where drugs or alcohol are being consumed) and may be subjected to a virginity test.

Homosexuality

Homosexual conduct is illegal under Syrian law, which is punishable by up to three years of imprisonment.

Stay healthy

Healthcare in Syria is well below Western standards, and essential medication is not always available.

Local pharmacies are well stocked with treatments for most common ailments such as stomach bugs and traveler's diarrhea. Pharmacists often speak a little bit of English. You can ask your hotel to call a doctor and visit your hotel room.

Of course, the best treatment is to stay healthy in the first place. When eating, pick busy restaurants.

If you have a treatment, take it with you. Only expect to find some medicines in Syria. Ask for a "foreign" EU or US brand if you have to buy something from a pharmacy. You will have to pay a premium for that, but at least you will increase the chances of having actual medicine. According to certain local pharmacists, some products come from uncertain origins and are ineffective.

Generally you can drink water from the tap. It should be safe, but if you're unsure, ask the locals first. This water is free compared to bottled water.

Respect

Syria is a majority Muslim country with long-established Christian, Jewish and Yazidi minorities. However, the Jewish community is down to only a handful of individuals in Damascus, with the vast majority having immigrated to Israel. Historically, religious groups lived in harmony, and religion was primarily considered personal. It was inappropriate to ask someone about their faith unless you knew them well. However, this has changed since the start of the Syrian Civil War.

Syria is a majority Muslim country with long-established Christian, Jewish and Yazidi minorities. However, the Jewish community is down to only a handful of individuals in Damascus, with the vast majority having immigrated to Israel. Historically, religious groups lived in harmony, and religion was primarily considered personal. It was inappropriate to ask someone about their faith unless you knew them well. However, this has changed since the start of the Syrian Civil War.

General etiquette

-

Syrians are indirect communicators. They are tempered by the need to save face and they will avoid saying anything that could be construed as critical, judgmental, or offensive.

-

Direct personal questions are commonly asked. To Syrians, it's not considered impolite, but rather it's a way to get to know someone fully. If you feel a question is too personal, simply give an indirect answer and move along.

-

Syrians tend to be affectionate to children. In Syria, it's perfectly normal for both men and women to interact with a stranger's child.

-

Syrians tend to speak loudly in groups. They also use aggressive body language and raise their voices in conversations; to most visitors, this implies that Syrians are an argumentative bunch, but Syrians tend to use emotions to convey interest in a conversation. What may seem like a shouting match in public may actually be a simple, friendly discussion!

Social customs and breaches

-

Never beckon a Syrian person directly, even if they have done something wrong in your opinion. Syrians are quite sensitive to being beckoned directly, and it is considered very rude manners. If you must give feedback, give a mix of both positive and negative feedback.

-

Don't talk someone down for having poor English skills. Many Syrians can speak English, usually as a second language. Making condescending statements such as "You speak very good English" is extremely rude.

-

Do not swear in front of women. This is applicable to male travellers. It is considered extremely rude.

-

It's common for Syrians to turn up to a place unannounced. When this happens, stop what you are doing and attend to your guests.

-

Never show the soles of your feet to others. This is considered very disrespectful, unless you are in the company of friends.

-

Don't spit in public or in the direction of others, even when obviously done without malice. It is extremely rude.

Clothing

Male and female visitors can generally wear whatever attire they would normally wear in their home countries. Contrary to what some Westerners may believe, it is possible for women to wear T-shirts and it is not necessary to wear long-sleeved tops unless visiting a religious site. Head covers are recommended when visiting Muslim religious sites. Dress as you would normally dress in the West to visit Christian religious sites, avoid wearing shorts at churches. Many local women dress in Western attire, especially in Christian neighbourhoods. Shorts are common for both men and women. Be mindful of your environment, outside of areas frequented by tourists it is wise to dress in more modest clothing.

Women who wish to attract less attention should wear shirts that reach the elbow, and have no revealing cleavage. T-shirts and jeans are acceptable attire in Damascus.

Religion

If you are of European ancestry most Syrians assume that you are a practising Christian. Most Syrians will also be puzzled by a suggestion that you are an atheist, due to the strong influence religion has in Syrian social and cultural life. The coastal areas are much more progressive when dealing with religion and the same applies to areas of Damascus most frequented by Western tourists such as Bab Touma, the Christian Quarter. The further you travel east, the more conservative people are. In order to avoid any protracted philosophical discussions, it is best to avoid identifying as an atheist or non practising Christian.

Things to avoid

Politics:

-

Approach discussions on Israel with caution. Israel's occupation of the Golan Heights is considered illegal by the vast majority of Syrians and many Syrians express negative sentiments against Israel. Unless you have a heart for prolonged discussions, avoid debates on Israel.

-

It is unwise to criticise or speak badly of the Syrian government. A comment heard by the wrong person can land you in legal hot water. Those who have fled Syria are more likely to have negative things to say about the Al-Assad government.

The war:

- Approach discussions on the civil war with caution. Millions of Syrians have fled their country and some have lost their loves ones in the war. Offer sympathy when the opportunity arises; Syrians will appreciate the gesture.

Connect

Phone

The international calling code for Syria is +963.

Internet

Syria has easy and cheap internet access. Internet is very common around the cities at internet cafés. The cafés are very friendly but in order to avoid being price gouged it is best to ask a local how much the internet costs per an hour before agreeing to sit down. It is best to avoid political debates regarding the Syrian government, or reading Israeli newspapers or websites on-line.

Prices for high-speed access are quite varied.

Population:16.9 MDial code:+963Currency:Pound (SYP)Voltage:220 V, 50 Hz