Big Bend National Park

Big Bend National Park

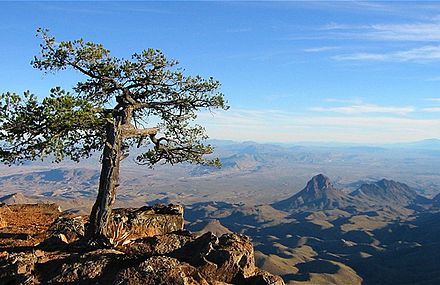

Big Bend National Park is vast and rugged area, and one of the least visited national parks in the continental U.S. With three distinct ecosystems, endless views, and powerful landscapes, Big Bend may leave you feeling like you've stumbled onto a well-kept secret.

Understand

Big Bend National Park is named for the huge left-turn the Rio Grande makes as the river snakes its way through the Texas desert — creating a natural boundary with Mexico and giving the state its distinctive bottom shape. Covering 801,163 acres (324,219 hectares, a bit smaller than Long Island) but with only 300-350,000 visitors a year, Big Bend is one of the largest national parks in the lower 48 states yet one of the least visited. Most of the park is backcountry — the brunt of activity is clustered around the few developed areas. Even during the busiest times, hitting a desert trail or backroad is all that's needed to find solitude; the rest of the year is so uncrowded, you'll feel like you have the park to yourself.

The busy season is from mid-November through the first of week of January (especially Thanksgiving weekend and the weekends near Christmas and New Year's Day) and again during Spring Break, when local college students get a week-long break (usually mid-March through April). Unless you're already in the area, Big Bend does not make a good day trip; the distances are just too vast. Ideally, plan on spending at least one full day in the park, though there is more than enough here for longer stays.

Pets are not allowed on trails, off the road, or on the river; there are no kennels in the park and the temperatures and wildlife can be hazardous — consider leaving Fido at home.

History

Big Bend National Park has an unusually rich history, the effects of which are present everywhere you look. The landscape is living testament: shaped over millions of years by volcanism, erosion, and enormous seismic events, it also still holds untold numbers of dinosaur fossils and sea creatures from when the area was engulfed by an ancient ocean.

Humans have inhabited the park for more than 10,000 years — first were Native American tribes such as the Chisos, about which little is still known and, more recently, the Comanche and Mescalero Apache; all of whom have left their mark in the form of rock art, mortar holes, and shelters. Mexicans and Anglo settlers would establish a presence later, building homes, farms, ranches and mines (some of which persisted until as recently as the 1960s), of which many ruins can still be found.

Lobbying from locals and other admirers of the area (notably frontiersman Everett Townsend, the "father of the Big Bend National Park") convinced the state of Texas to set aside land for the park in 1933, which was to be named "Texas Canyons State Park". In 1944, Big Bend National Park was established, and it has been slowly growing ever since — thousand-acre tracts are still being purchased, including the Harte and Fay Ranches in 1989 and 1994. There are tentative plans to integrate the park with its neighbor to the west, Big Bend Ranch State Park, including trails that may connect the two.

Landscape

The park's geography can be categorized into three distinct environments: desert, mountain, and river. The majority of Big Bend National Park encompasses Chihuahuan Desert, crisscrossed by arroyos (dry creek beds), washes and the occasional spring; wherever water exists, small oases of green vegetation flourish. Sprouting from the desert are numerous hills, mountains, and rock formations — most of which are limestone but others are of volcanic origin.

The Rio Grande (Spanish for "Big River", although in Mexico it's called Rio Bravo del Norte or just Rio Bravo, meaning "Wild River") flows south and east from its origin in Colorado and eventually passes through the park before emptying into the Gulf of Mexico after a journey of 1,885 mi (3,034 km). Here the river forms the 118 mi (190 km) long southern boundary of the park, passing through three major canyons (Santa Elena, Mariscal, and Boquillas) and through the desert, where green stands of trees, tall grasses and other riparian life cling to its banks.

Flora and fauna

Big Bend National Park is blessed with an exceptional array of plant and animal life. In the desert grow succulents such as lechuguilla (a type of agave), yuccas like the impressive giant dagger species, numerous types of cacti such as prickly pear, and abundant grasses and shrubs such as ocotillo, candellila, and sotol (all of which have numerous practical uses), as well as the famous century plant (or Havard agave), which only blooms once in a lifetime and then dies. The best time of year to see the gorgeous cactus blooms is March and April and the mountains are another great place to see wildflowers. In the mountains and near the water grow pleasantly surprising stands of juniper, ponderosa pines, piñon pine, Douglas fir, Texas madrone, quaking aspen, the unique Chisos Oak (one of five Oak species here), and many others.

Big Bend is one of the best bird-watching areas in the country, as many birds pass through here along migratory routes — more than 450 species. Big Bend is the only place in the U.S. where you can spot the Colima Warbler (check Boot Canyon along the South Rim trail from mid-April to mid-September). The Chisos Basin is a great place for birdwatching in general, but the best place is considered to be along the river, such as near Rio Grande Village and Cottonwood Campground. Among the countless species you may spot include roadrunners, woodpeckers, cardinals, quail, flycatchers, herons, hummingbirds, cliff swallows, owls, hawks, golden eagles, vultures, and peregrine falcons.

A great variety of animals make their home here, such as pig-like javelinas (pronounced "have a LEE nah" — and they're thought to be more closely related to hippopotamuses), mule deer, jackrabbits, skunks, raccoons, rock squirrels, kangaroo rats, coyote, foxes, and, in the mountains, rare black bears, mountain lions (AKA "panthers"), and white-tailed deer. They are all mostly shy, but you have a good chance of seeing them along roadways or even in the developed areas, especially starting at twilight. You may also glimpse snakes such as the "red racer" (western coachwhip), huge bull snakes (which have a tail like a rattlesnake but are not dangerous), and a small variety of venomous snakes. Lurking among the rocks are lizards: common whiptails, crevice spiny lizards, and earless lizards, along with the rare Texas horned lizard and large leopard and collared lizards. Around the river live turtles such as the Big Bend slider, amphibians such as the leopard toad, and mammals such as beavers. The endangered Mexican long-nosed bat is found only in the Chisos Mountains in the United States, while the entire world's population of Big Bend mosquitofish (or Gambusia) is found in one pond, near the Rio Grande Village.

Climate

As with most deserts, expect the weather to be mostly hot and dry, with low humidity and cooler nights. July through October is the rainy season, where sudden downpours — and consequently flash floods — are possible; though rain usually doesn't last long and the water drains away quickly. Thunderstorms make for an epic spectacle and may lead to rare sights, such as Pine Canyon Falls. The weather here can be significantly different from nearby areas; it might be overcast and rainy in nearby Alpine but clear and sunny in the park, so don't get too discouraged by local conditions. The park provides a weather hotline at +1 432 477-1183.

- Spring and fall: The onset of milder temperatures brings more visitors to the park. It can get quite windy in the spring, while the fall can experience rain until around September or October.

- Winter: Winter is another popular time for visitors; expect cool weather interspersed with pleasant warm spells and occasional cold snaps — snow and frost are not unheard of. Nights can be particularly cold.

- Summer: This is the least busy season as temperatures can be brutal, often topping 100°F (38°C). May and June are the hottest months; the start of the rainy season in July tames the heat just slightly.

Visitor information centers

The park visitor centers are a great place to start your visit at the park, providing such essentials as maps, permits, park news, and advice. They're also a great place to learn more about the park; they all provide exhibits on aspects such as park history, geology, and wildlife (some also have movies); each center also has a bookstore.

All visitor centers provide public access to restrooms, water, and pay phones.

- Castolon Visitor Center, 29.133606°, -103.514176°. Nov-Apr 10AM-4PM daily, May-Oct closed. Provides exhibits on the rich history of the surrounding buildings and area known as the Castolon district. Although the visitor center is seasonally closed, the nearby store is open year-round. 2019-09-18

- Chisos Basin Visitor Center, 29.270414°, -103.300416°. Year round, 8ː30AM-4PM daily. Nestled amidst the well-developed Chisos Mountain Basin area, this popular visitor center has detailed exhibits on the mountain wildlife you may encounter in the Chisos. Many trail-heads and other facilities are nearby. 2019-09-18

- Panther Junction Visitor Center, 29.32784°, -103.205895°, +1 432 477-2251. Year round, 8ː30AM-5PM daily. Park orientation film every 30 minutes 9ː30AM-4PM. It's roughly at the center of the park, and is considered to be the "main" visitor center — the park headquarters are also nearby. The center showcases many neat exhibits, including a 33 ft (10m) long replica of the first-ever intact Quetzalcoatlus specimen (a pterosaur fossil which was discovered in the park in 1971). Also nearby is a park bookstore, post office and the Panther Path trail. 2019-09-18

- Persimmon Gap Visitor Center, 29.660035°, -103.173629°. 9AM-4:30PM daily. Provides nice exhibits on the various activities Big Bend National Park has to offer, as well as how to stay safe. Possibly your first encounter with a restroom after a long drive!

- Rio Grande Village Visitor Center, 29.185265°, -102.962198°. Nov-Apr 9:30AM-4PM daily, May-Oct closed. Houses exhibits on wildlife found in the nearby Riparian (river) environment inside; outside is a pleasant desert garden. Although the visitor center is seasonally closed, the nearby store is open year-round.

Get in

Big Bend National Park is one of the most remote parks in the United States — it can be a challenge to get to since it's not really near anything (which is really half of the adventure).

By car

Services between towns range from limited-to-nonexistent and distances are vast, so stock up on gas, water, and other essentials beforehand and re-stock whenever possible. However, roads are in good condition and points of interest are well-marked (qualities generally shared throughout the Texas highway system). Although the roads here can be extremely lonely, don't get lulled into thinking it's safe to speed — the area is regularly patrolled by cops. The roads are also scenic and sometimes quite curvy, so it pays to take it slow.

Services between towns range from limited-to-nonexistent and distances are vast, so stock up on gas, water, and other essentials beforehand and re-stock whenever possible. However, roads are in good condition and points of interest are well-marked (qualities generally shared throughout the Texas highway system). Although the roads here can be extremely lonely, don't get lulled into thinking it's safe to speed — the area is regularly patrolled by cops. The roads are also scenic and sometimes quite curvy, so it pays to take it slow.

All major roads into the park now have US Border Patrol checkpoints, although they are not always manned. If there is a flashing light posted outside, you'll have to stop and you may get asked a few questions or inspected. Non-US citizens should carry documentation and be prepared for questioning as when entering the US.

There are two entrances to the park and three main routes to reach them:

- US-385 south from Marathon. This is the fastest route when approaching from points east. This route leads to the north entrance of the park at Persimmon Gap after about 40 mi (64 km), then another 30 mi (48 km) south to park headquarters.

- TX-118 south from Alpine. This is the quickest route from the west. There is a bit more development along this stretch compared to the Marathon route but they are equally scenic. The small communities of Study Butte-Terlingua lie near the end of the route. Shortly afterward, the west entrance to the park is reached at Maverick Junction — about 75 mi (121 km) to this point, then another 25 mi (40 km) east to park headquarters.

- Ranch Road 170 east from Presidio. This is the quickest route to Big Bend if coming from Mexico or Presidio (and arguably the most scenic route); from anywhere else it's the slowest route. Ranch Road 170 follows the Rio Grande River, hemmed in by foreboding mountains. In sections it's akin to a roller coaster ride and can get very steep; it's not for the faint of heart or those driving RVs or other long vehicles. Towards the end you'll pass Lajitas and then join up with Tex. 118 near Study Butte-Terlingua, for a distance of about 65 mi (105 km) to that junction, then another 30 mi (48 km) or so to park headquarters.

By plane

There are no landing strips in the park. The largest commercial airport is at El Paso; the rest are smaller, local gateways. Once you've arrived, you'll need to drive the rest of the way to the park. The nearest commercial airports are:

- Del Rio International Airport (IATA: DRT) at Del Rio. From Del Rio simply take US-90 west to Marathon; a total trip of about .

- El Paso International Airport (IATA: ELP) at El Paso, this is also the nearest large city. From El Paso, take I-10 east to Van Horn, then take US-90 southeast through Marfa then to Alpine — it will turn into US-67 en route. The total distance is about .

- Midland International Airport (IATA: MAF) at Midland, considered the gateway to the Big Bend region. From Midland-Odessa, take I-20 west then TX-18 south to Fort Stockton. From there take US-385 south to Marathon for a total of about .

- San Angelo Regional Airport (IATA: SJT) at San Angelo. From San Angelo take US-67 south to I-10, then head west until Fort Stockton and take US-385 south to Marathon. The total distance is about .

- There is also an airport for private planes at Lajitas.

By public transportation

There is no public transportation into the park, so you'll need to provide your own.

Farther out

- From San Antonio, you have two options. The fastest route is to take I-10 west to Fort Stockton then take US-385 south to Marathon; around 440 mi (708 km) total. The other option is shorter, less traveled, and much more scenic, but has lower speed limits — take US-90 west through Del Rio then continue to Marathon; a total of about 397 mi (639 km). On the latter route there are no services after Del Rio until you reach tiny Sanderson; a distance of about 120 mi (193 km).

- From Austin, take US-290 west until you reach I-10, then continue west until Fort Stockton as on the San Antonio route; about 465 mi (748 km) total.

- From Dallas/Fort Worth, take I-20 west to Midland-Odessa then take TX-18 south to Fort Stockton; from there it's the same as the San Antonio route for a total trip of around 570 mi (917 km).

Fees and permits

The entrance fee will get you a seven-day pass, in the form of a paper slip which you attach to your vehicle's windshield. The park gates are always open; if you arrive after hours you can get your pass in the morning from the Panther Junction Visitor Center. Entrance fees as of 2020 are:

- $12 - Individual

- $25 - Motorcycle

- $30 - Per Vehicle

- $55 - Big Bend Annual Pass

- Fees for educational groups (who may be able to get in free) and commercial tours have special rules — contact the park for details.

Backcountry permits

Depending on your planned activities, you may need to obtain a backcountry permit. Camping at developed sites and day hiking do not require a permit. Certain types of day-use, such as floating the river or traveling by horse, necessitate a permit but it's free of cost. For any overnight backcountry use, the required permit is $10. There's no reason not to get one; it goes to a good cause (maintaining the backcountry for future visitors) and helps keep you safe. The park will record your itinerary and other information, such as your shoe print — all of which will make you easier to find in case of an emergency — plus they'll give you critical information on current trail and road conditions.

Backcountry permits are good for up to 14 consecutive nights. The permit can be obtained up to 24 hours in advance at any park visitor center during business hours (for the main center at Panther Junction, the hours are 8AM-6PM — other visitor centers have variable hours). If you arrive after business hours, you are not permitted to camp in the backcountry. In addition, they can only be purchased in person, on-site. If you arrive by car, you must have a license plate.

Get around

There is no public transportation within the park; the car is by far the most common option for area travelers and it's a good way to negotiate the vast expanses. The signage throughout the park is excellent and the paved roads are well-maintained.

There are two main roads in the park: TX-118, which travels from the park's west entrance near Maverick Junction eastbound 23 mi (37 km) until it meets the other main road, US-385 at Panther Junction, where there is a gas station and park headquarters. From here TX-118 continues southeast, ending after 20 mi (32 km) at Rio Grande Village, where gas can also be purchased. Back at the junction, US-385 begins here and heads northwards for 26 mi (42 km) to the north entrance, near Persimmon Gap. These two roads form the shortest route through the park.

By car

The park speed limit is 45 mph (72 km/h). Drivers will encounter not only steep grades and blind curves, but also share the road with the occasional bicyclist or wildlife (deer and javelina, in particular, lurk on or near the road starting at dusk) — so be sure to follow the speed limit. Surprisingly, the number one cause of fatalities in the park is drunk drivers — don't become one yourself and add to the statistic. The park's network of unpaved backroads contain some routes suitable for any car, but some require a high-clearance or 4WD vehicle to drive safely. All vehicles must be street-legal and all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) are not allowed in the park.

By bicycle

For traveling the park at a more relaxed pace, totally immersed in your surroundings, nothing beats a bike. No mountain biking is permitted but you have free access to all park roads, both paved and unpaved. Good options for novices are the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive and the road from Panther Junction to Rio Grande Village; both of which are downhill — make sure to have a shuttle waiting at the other end unless you're prepared for the strenuous trip back up. The backroads offer the real adventure — the Old Ore Road is a good choice for more experienced bikers. Biking is not common in the park yet, so most drivers will not be expecting you; be cautious on curves and after dark. Be sure to check your tires and bring a repair-kit, a good level of fitness, and plenty of water. Desert Sports offers bike rentals, tours, and shuttle services.

By horse

Although there are no outfitters that rent them, you can bring your own horse (yes, B.Y.O.H.) — but also make sure to get a (required) backcountry permit and to be prepared. Horses are restricted to the backcountry, which means paved roads, developed campsites and trails, and much of the Chisos Mountains are all off-limits. Grazing is not permitted, so food has to be brought in. A good camping spot is at Government Springs (Hannold Draw), which has a corral (large enough to accommodate 8 horses) and lies about 5 mi (8 km) north of Panther Junction.

On foot

Aside from hiking trails, traveling the park by foot as your primary mode of transportation should only be attempted by those who are extremely well-prepared and fit.

See

Big Bend National Park is a land of seemingly endless landscapes of rolling desert, punctuated by rock outcrops, canyons, and foreboding mountains; all framing the ever-present green ribbon that is the Rio Grande. However, anyone picturing some sort of fantasia-in-stone like Utah's national parks or an austere desolation like Death Valley may come away disappointed. Although Big Bend's dominating landscape may leave one feeling in awe and a bit humbled, the real magic of the park lies in its hidden treasures — rounding a corner and finding an oasis of life, diverse and vibrant, where you least suspect it; gazing at endless vistas from your own private viewpoint; or stumbling upon a striking formation of ancient rock, wondering if maybe you're the first person to have ever laid eyes upon it.

You could squeeze in all the major sights in a full day of driving, but that would be missing the point; Big Bend rewards the patient traveler. It is well worth the effort to hang around a bit longer, venture off the paved roads, and let the grandiosity of it all sink in. For those on a tight schedule, the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive and Chisos Basin Road are popular itineraries that can be seen in a day with some stops. With more time, it is worth exploring Rio Grande Village and the rest of the park further, as well as partaking in other activities such as hikes or floats down the river.

North Entrance to Panther Junction

This route begins on US-385 at the north entrance, near Persimmon Gap, and heads south along a gentle, downward slope 26 mi (42 km) to Panther Junction. Persimmon Gap is literally that; a natural opening between the otherwise wall-like Santiago Mountains. Very shortly after passing through it you'll find the north entrance station and the Persimmon Gap Visitor Center; there are also picnic tables here.

On the southern face of the mountains to the east is a very noticeable section that looks like it was blown out by dynamite; this is the result of a natural rock slide that occurred in 1987. A few miles south is an exhibit on Dog Canyon, which is visible as a distant notch in the mountains to the east. As you continue through the shrub-filled landscape, you'll see the Rosillos Mountains far to the west and the steep Sierra Del Carmens forming a seemingly impassable barrier to the east. Much of the huge swaths of land to the west was purchased from the Harte Ranch or is owned by the still-operating Rosillos Ranch, although there is not much to see from the road.

About midway through you'll find the east-bound turn-off for the Dagger Flat Auto Trail and, further south, a fossil bone exhibit which in 2017 was upgraded with a new building and detailed displays. Along the way you'll cross the Tornillo Flat, a noticeably elevated (and flat) geological feature intertwined with usually-dry creek beds. As you approach Panther Junction, the mighty Chisos Mountains, initially appearing quite puny in the distance, slowly dominate the view.

West Entrance to Panther Junction

Although this route mainly serves as a major artery to other notable roads, it is also arguably the more grand approach into the heart of Big Bend National Park. Beginning on TX-118 at the western edge of the park, this leisurely route passes through relatively gentle desert landscape 23 mi (37 km) to Panther Junction. Your first encounter is the Maverick Entrance Station (unlike the north entrance, there is no visitor center here). After entering, you'll pass through endless fields of cacti and other desert flora; there are several road-side exhibits explaining the ecosystem and wildlife you may see, as well as plenty of opportunities to stop, walk around, and admire the vast views and expanses.

Soon after the entrance is Maverick Junction, where unpaved Maverick Road wends its way south. Continuing on, you may notice some of the many distinctive peaks and rock formations that characterize Big Bend. To the south, the landscape slopes downhill revealing the Mesa de Anguilla in the distance. In the midst of it all stands Tule Mountain, the top of which looks a bit like a slanted mohawk. Far off to the southwest you may spy a distant notch in the mountains: this is Santa Elena Canyon. To see it up-close, follow the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive — the junction for which you'll encounter 10 mi (16 km) from the entrance.

To the north are rolling hills and distant mountains, such as Croton Peak, which looks like it has a tooth sprouting from its top. You can spy it from the Croton Spring Road junction, followed soon after with turn-offs for Paint Gap Road and Grapevine Hills Road — all of which are unpaved and lead to backcountry camp sites, a worthwhile hiking trail (for the latter road), and more views. Along the way, appearing from seemingly nowhere are the impressive, looming Chisos Mountains. The road sidesteps them by curving north before reaching the Chisos Basin Road junction, a total of 20 mi (32 km) from the west entrance. Continue down the road another 3 mi (5 km) to reach Panther Junction.

Chisos Basin Road

Built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, this steep, curvy road climbs for 6 mi (10 km) into the Chisos Mountains before ending in the Chisos Basin, providing sweeping views of the mountains and deserts along the way. This road is not recommended for trailers longer than 20 ft (6 m) or RVs longer than 24 ft (7 m). The Chisos Basin Road junction is off of TX-118 near the center of the park; 20 mi (32 km) east of the west entrance, 10 mi (16 km) east of the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive turn-off, and 3 mi (5 km) west of Panther Junction. From there, the road heads southwards and immediately begins its ascent into the Chisos, the third tallest range in Texas (the meaning of "Chisos" is unclear — usually said to be either an American Indian word for "ghost" or "spirit", or derived from an old Castilian word for "enchanted").

Built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, this steep, curvy road climbs for 6 mi (10 km) into the Chisos Mountains before ending in the Chisos Basin, providing sweeping views of the mountains and deserts along the way. This road is not recommended for trailers longer than 20 ft (6 m) or RVs longer than 24 ft (7 m). The Chisos Basin Road junction is off of TX-118 near the center of the park; 20 mi (32 km) east of the west entrance, 10 mi (16 km) east of the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive turn-off, and 3 mi (5 km) west of Panther Junction. From there, the road heads southwards and immediately begins its ascent into the Chisos, the third tallest range in Texas (the meaning of "Chisos" is unclear — usually said to be either an American Indian word for "ghost" or "spirit", or derived from an old Castilian word for "enchanted").

The initial, hilly stretch of the drive passes through Green Gulch, known for its (rare) mountain lion sightings. As you climb, it seems as if you're entering a different world as the cacti and shrubs are slowly augmented and then replaced by forests of pines, oaks, and other trees that seem quite out-of-place in the desert. As the road gets steeper, you will pass the parking lot that serves as the trail-head for the excellent Lost Mine Trail. As you near the highest point at Panther Pass, the road becomes especially curvy and steep (nearly 10% grade at points); exercise caution. The road then drops into the Chisos Basin: a huge forested depression at an elevation of 5,400 ft (1,646 m) surrounded by mountain peaks and chock full of breathtaking views.

Past a turn-off to the campgrounds, the road finally ends in the Chisos Basin developed area, where you'll find the Chisos Mountains Lodge and the visitor center, as well as dining, lodging, and numerous trail-heads. This is a good place to get out, hang around awhile, and gawk at your surroundings. Immediately noticeable to the northeast is a large V-shaped gap in the mountains, providing a magnificent view of the desert miles below (and sunsets, occasionally); this is called The Window. The Window View Trail is a good introductory hike, providing what its title describes. Face due south and a bit to the east to spot Emory Peak, the highest point in the park at 7,832 ft (2,387 m). One of the most distinctive mountains is Casa Grande, Spanish for "Big House" (you'll know it when you see it). Closer at hand are several impressive rock pinnacles, including a particularly tall one very close to the Lodge area.

Panther Junction to Rio Grande Village

This 21 mi (34 km) route traverses from the center of the park to its southeastern corner, through sweeping desert landscapes towards the Rio Grande. Beginning at its junction with US-385, TX-118 skirts the massive Chisos Mountains before heading southeast, gently descending around 2000 ft (610 m) in elevation along the way. The distant mountains to the north and east are the Sierra Del Carmen and the Sierra Del Caballo Muerto (Dead Horse Mountains). Looking to the west, the road continues to follow the Chisos until it slowly peals away from them, although other isolated peaks stand out along the way, such as flat-topped Chilicotal Mountain (named for the plant which dots its slopes). There are many turn-offs to various unpaved roads along the way; offering access to many backcountry campsites, views, historical sites, and hiking trails, though you may need a high-clearance vehicle to enjoy some of them; be sure to check individual listings.

The delicate nature of the desert ecosystem is on display early along the route, where the landscape is dominated by vast fields of rather stunted grass — the victims of overgrazing from ranching that ended more than a half-century ago but is still in the process of recovering. As the route descends further, more traditional desert flora take over. Not far from Panther Junction are two turn-offs for unpaved roads; one is a short ride to the K-Bar backcountry campsite to the east, and the other is for Glenn Springs Road (where Nugent Mountain towers directly to the west). Soon after is the turn-off for Dugout Wells; a short, unpaved drive where you'll find the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Trail, a nice picnic area, and a sort of mini-oasis in the desert, thanks to the water pumped from the wells by an old-style windmill built here (making this a decent bird watching spot).

Much further along you'll encounter more turn-offs leading to unpaved roads, including one for the River Road, another for Hot Springs Road, and finally Old Ore Road. Continuing on through a short tunnel through the rock, you'll come across a stop for the Rio Grande Overlook which peers down towards Rio Grande Village and the river beyond. Next is a junction that leads either southwards to the end of the drive at Rio Grande Village, or eastbound for 4 mi (6 km) more towards the mountains and Boquillas Canyon; the longest canyon in the park. On the latter route towards the canyon, soon there is a turn-off for the Boquillas Crossing, where tourists carrying valid passports and American dollars in small bills can visit the Mexican village of Boquillas del Carmen. Further on, there's another turn-off for the Boquillas Canyon Overlook; continuing on the road leads to a parking lot and the trail-head into the canyon itself. Although impressive, it is perhaps slightly less awe-inducing than Santa Elena Canyon; Boquillas can be a less-crowded alternative or a good build-up if you plan on seeing both, but is worth seeing either way.

Back at the junction, choosing south will lead shortly to Rio Grande Village, which is not actually a village but rather a developed area set against the river amidst pleasant stands of trees and lush grasses. The short Rio Grande Village Natural Trail showcases the riparian (river) ecosystem here. In addition, you'll find campgrounds, a store, and a visitor center (all of the same name), as well as the remaining structure of Daniel's Ranch a bit to the west along the river. Picnic areas can be found at both the campgrounds and near the ranch.

Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive

Specially designed by geologist (and the park's first superintendent) Ross Maxwell to show off Big Bend's rich geological history, this curvy 30 mi (48 km) road descends through desert down to the Rio Grande past vistas, mountains, and historical sites before ending at spectacular Santa Elena Canyon. The Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive begins from TX-118 on the western side of the park, about 13 mi (21 km) west from Panther Junction and 10 mi (16 km) east of the west entrance and meanders further south and west to the border; figure on about a 45 minute-to-1 hour trip one way, not counting stops. The terrain on this side of the park is particularly jumbled and rugged; many of the distinctive rock formations here and throughout the park owe their existence to millions of years of erosion and volcanic activity. In particular are "hoodoos", which look like thin chimneys or columns of piled rock, and groups of straight ridges on the side of mountains, called "dikes".

The route starts by heading south, shadowing the mighty Chisos Mountains to the east. A few miles in, if you look up you can see the large V-shape of The Window, framing the Chisos Basin miles beyond. After about 4 mi (6 km) comes the first turn-off: Sam Nail Ranch, one of the many abandoned structures in the park from the old days when it was settled; now you can find trees, benches, and a windmill in this peaceful setting. Down the road another 4 mi (6 km) is the turn-off for the Blue Creek Ranch Overlook, which peers down at the old Homer Wilson Ranch house; there's also a trail-head here which will lead you there and beyond. Very soon after is the Sotol Vista Overlook turn-off; stop here for a grand view of the desert spread out below and the mountains behind you. Far off in the distance to the west, Santa Elena Canyon is visible as a large gap in the mountains. Unfortunately, sometimes views in the park are hampered by haze, the frequency and degree of which is increasing with time — surprisingly this air pollution is blown all the way here from refineries in Mexico and East Texas, along the Gulf Coast.

After a brisk descent, the next stop, about 3 mi (5 km) away, is the turn-off for the trail-head to the Burro Mesa Pour-off. Continue on about another 3 mi (5 km) for a stop that serves as the starting point for the Chimneys Trail and then, near the Blue Creek crossing, a roadside exhibit for Goat Mountain: a peak of volcanic origin. You may catch some early glimpses of the subject of the next stop: Mule Ears Viewpoint, which showcases this perfectly named rock formation. After a total drive of about 20 mi (32 km), just before the junction that serves as the western terminus of the River Road, is the stop for Tuff Canyon; formed of ancient compressed volcanic ash and then slowly carved by water, this striking white-walled canyon offers several viewpoints from the top as well as a trail that descends into it.

After a 22 mi (35 km) drive you'll reach the Castolon Historic District, where exhibits describe how it served as a gathering place for settlers in the early 1900s, just as it still does today. Here you'll also find restrooms, picnic tables, the Castolon Visitor Center, the Cottonwood Campgrounds, and La Harmonia Store. Built in 1920, La Harmonia — together with the original store, the Alvino House (built in 1902, making it the oldest complete adobe structure in the park) — served local communities as a hardware store, bank, jail, and whatever else was needed. Today, you can still buy limited groceries and supplies year-round. There are also other adobe ruins scattered about the area, as well as two cemeteries.

After stretching your legs, continue the final 8 mi (13 km) to reach Santa Elena Canyon. This section of road, in particular, is susceptible to flooding after heavy rains. Even if there is a seemingly small amount of water on the road, do not cross — it is always safer to wait it out, and floods usually drain away quickly in the park. Along the way you'll also pass the junction with the southern end of unpaved Maverick Road. Once at the parking lot at the end of the drive, a short path through the brush will lead you to a full view of the canyon. With the Rio Grande flowing beneath limestone walls 1,500 ft (457 m) high (the Mesa de Anguilla constitutes the U.S. side, the Sierra Ponce the Mexican side), Santa Elena Canyon is often regarded as the most beautiful of the Big Bend's canyons and is perhaps the park's most well-known site; there is no substitute to seeing it face-to-face. There is a worthwhile trail here that leads into the Santa Elena; floating the river through the canyon is another popular activity.

Do

You may hear it again and again from locals and Big Bend National Park veterans: the best way to truly experience the park is to step out of the car and do something. And it's true! Seeing the park by car gives you some broad impressions, but it's not until you stop, take a breath, and let your surroundings engulf you before Big Bend's true beauty reveals itself. There are activities for any age or fitness level and to make things really easy, you can go on a (free!) daily ranger-led program or arrange a guided tour with any of the excellent local outfitters. The important thing is to get out there!

Driving the backroads

Here, sometimes driving Big Bend's network of rugged, unpaved backroads is an adventure unto itself. They can take you to historical sites, trails, and other remote areas of the park that are otherwise inaccessible. No matter which road you take, expect a bumpy ride; come prepared and be sure to take it slow. Road signage is generally very good in the park.

Improved roads

In optimal conditions, these dirt roads are passable to any vehicle. Weather can significantly degrade their condition, sometimes making them impassable to sedans and the like; always be sure to ask about road conditions before setting out.

- Croton Spring Road (2 mi / 3 km round-trip). This short road leads to two backcountry campsites; the turn-off is 9 mi (15 km) west of Panther Junction on TX-118 and heads north.

- Dagger Flat Auto Trail (14 mi / 22 km round-trip). An intriguing "trail" that winds eastwards to a forest of otherwise-rare giant dagger yucca. They can potentially bloom anytime of year but March and April are generally a good time to see flowers blooming in the park in general. The park also offers a trail-guide for $1 at visitor centers. The turn-off is on US-385 about midway between Panther Junction and Persimmon Gap; the road is narrow and takes about 2 hours total.

- Grapevine Hills Road (15.4 mi / 25 km round-trip). Most significantly, a road that leads to the Grapevine Hills trail-head after about 7 mi (11 km). The road continues a bit further to a backcountry campsite but may be too rough for sedans. The turn-off is about 3 mi (5 km) west of Panther Junction on TX-118 and heads north.

- Hot Springs Road (4 mi / 6 km round-trip). A narrow road that leads most of the way to the Hot Springs (there's another half-mile (800 m) hike after that). This road is not recommended for RVs and other overly large vehicles. The well-marked turn-off is near Rio Grande Village on the southwestern leg of TX-118.

- Old Maverick Road (14 mi / 22.5 km one-way). A long, flat road that connects TX-118 near the park's west entrance to the Ross Maxwell Scenic Road near Santa Elena Canyon. En route there are a few backcountry campsites, the trail-head for the western end of the Chimneys Trail, as well as historical sites such as Luna's Jacal, a very rustic adobe structure that served as the home of quite the character, one Diego Luna — its best to experience the exhibit in person. Plan on about an hour of driving.

- Paint Gap Road (5 mi / 8 km round-trip). This road heads towards the Paint Gap Hills to several backcountry campsites, eventually entering the Gap itself where it is very rough. Vehicles that are not high-clearance should turn back after the PG-3 campsite. The turn-off is about 6 mi (10 km) west of Panther Junction on TX-118 and heads north.

Primitive dirt roads

For true adventure, driving the more remote and less maintained "primitive" dirt roads are the way to go — with the right vehicle and preparation. These roads are rough, bumpy, sandy, rocky, or worse and require a high-clearance vehicle; sometimes four-wheel drive (4WD) is also required (and is always optimal). Like the Improved Roads, weather can significantly degrade their condition, sometimes making them impassable for any vehicle; always be sure to ask about road conditions first.

- Black Gap Road (8.5 mi / 14 km one-way). Driving Black Gap Road really is an adventure unto itself; this road is totally unmaintained and crosses extremely rugged country (and is scenic to boot). Not only is a 4WD vehicle mandatory, but 4WD experience is also necessary. Black Gap Road connects Glenn Spring Road, about 7 mi (11 km) from its north entrance or 8.5 mi (14 km) from its south entrance, to the River Road East, about 21 mi (34 km) from its entrance near Rio Grande Village. A backcountry campsite is found along the way.

- Glenn Springs Road (16 mi / 26 km one-way). This road winds its way between the Chisos and Chilicotal Mountains to the ruins of the small village of Glenn Springs, abandoned around 1920 and still home to crumbling adobes and other structures. The north end of the road intersects with TX-118 about 4.5 mi (7 km) east of Panther Junction (just west of the Dugout Wells turn-off) and ends at the River Road, 9.6 mi (15 km) from its eastern terminus near Rio Grande Village. Glenn Springs Road also serves as a connector to several other roads, including the 4 mi (6 km) long Pine Canyon Road which ends at the Pine Canyon trail-head (the turn-off lies 2.3 mi / 4 km from the TX-118 northern start point) and the 5.3 mi (8 km) long Juniper Canyon Road which leads to the Dodson and Juniper Canyon trail-heads (4.5 mi / 7 km south of the Pine Canyon Road turn-off; 4WD required). Several backcountry campsites are along the way as well.

- Old Ore Road (26 mi / 42 km one-way). A long, scenic road that provides close-up views of the hills and mountains to the east and was once a mining transport route. Several backcountry campsites and trail-heads lie along the way, including the Ernst Tinaja Trail near the southern terminus. The north end of Old Ore Road begins at the Dagger Flat Auto Trail about 2 mi (3 km) from its entrance and heads southward before ending at TX-118 near Rio Grande Village. A 4WD vehicle is recommended; allow a half-day or more.

- The River Road (51 mi / 82 km one-way). An epically long road that spans the remote southern portion of the park, generally (sometimes only vaguely) following the course of the Rio Grande. For some Big Bend adventurers, driving the length of the road is a rite of passage. Along the way are many side roads, backcountry campsites, trail-heads to some of the park's most isolated areas (including the Mariscal Canyon Trail), and sections of the park most visitors never see. The east end of the River Road lies off of TX-118 near Rio Grande Village, just west of the Hot Springs Road turn-off, while the west end of the River Road intersects with at the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive near Tuff Canyon, about 2.5 mi (4 km) east of Castolon (both turn-offs are marked). About 20 mi (32 km) west from the eastern terminus you can find the ruins of Mariscal Mine and the surrounding village, abandoned in the 1940s and an important producer of the nation's supply of mercury. The western portion is less traveled and more rugged; allow at least a day to travel the entire length.

Floating the river

One of the quintessential Big Bend experiences is floating the Rio Grande through one of its marvelous canyons, whether it be on a raft, by canoe, or by kayak. Side canyons and hikes await for the adventurous, and a variety of trip lengths are possible, from half a day to more than a week. You can bring in your own equipment or rent from a tour operator. For novices and those who don't want to bother with the logistics, a guided river trip is very convenient. Travelers of any age can participate; with raft tours, they all do the work while you sit back and relax. Self-paddled kayaking and canoeing are easy enough here for even first-timers to pick up and offer satisfying freedom. Expect to pay from around $65 for a half-day trip up into the $1000s for week-long (or more) adventures.

One of the quintessential Big Bend experiences is floating the Rio Grande through one of its marvelous canyons, whether it be on a raft, by canoe, or by kayak. Side canyons and hikes await for the adventurous, and a variety of trip lengths are possible, from half a day to more than a week. You can bring in your own equipment or rent from a tour operator. For novices and those who don't want to bother with the logistics, a guided river trip is very convenient. Travelers of any age can participate; with raft tours, they all do the work while you sit back and relax. Self-paddled kayaking and canoeing are easy enough here for even first-timers to pick up and offer satisfying freedom. Expect to pay from around $65 for a half-day trip up into the $1000s for week-long (or more) adventures.

Be sure to have essential safety equipment: life vests, extra oars/paddles, first aid kit, and patch kit/pump (for inflatable watercraft). Tour operators provide most or all of these for free. Water levels affect what is possible on your trip, so be sure to inquire about it at the park or with your tour company. Generally, the higher the water level is, the faster the river is flowing and certain sections may become rougher. Low levels might make it impractical to float by raft, for example, but make paddling upriver (so-called "boomerang" trips) a possibility. Generally the river is at its highest summer through early fall and lowest during winter. A backcountry permit is also required for any river-use; they can be obtained at the Panther Junction Visitor Center. There are many park guidelines to be followed and certain take-outs are on private land and require permission, so be sure to inquire ahead.

- Boquillas Canyon. 33 mi (53 km) (2–4 days). This route offers the longest but most gentle journey, rated as a Class I-II. Like all sections, there are plenty of sights and possible hikes along the way. The customary put-in is at Rio Grande Village with a take-out outside of the park at Heath Canyon near La Linda, Mexico — reached by following FM-2627 southeast for 28 mi (45 km) (the turn-off is just north of the Persimmon Gap park entrance).

- Mariscal Canyon. 10 mi (16 km) (1–2 days). The shortest canyon and also the most remote, Mariscal offers the most solitude. Depending on the water level this trip is considered Class II-III, with one small rapid called The Tight Squeeze. The put-in (Talley) and take-out (Solis) are both reached from the unpaved River Road; count on a rough 2 to 2.5 hour drive requiring a high-clearance, preferably 4-wheel drive vehicle. The little-traveled section between Santa Elena Canyon and Mariscal is sometimes called "The Great Unknown".

- Santa Elena Canyon. 20 mi (32 km) (1–3 days). Undoubtedly the most popular trip (and some say most spectacular). This section is usually Class II-III, except during high-water levels where a rapid called Rock Slide can be Class IV. Fern Canyon, about 3 mi (5 km) downstream from Rock Slide (or 2 mi / 3 km upstream from the other end of the canyon), is a popular stop for exploring. The usual put-in is at Lajitas, outside of the park, and the take-out is near Castolon, off of the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive.

- The Lower Canyons. 83-115 mi (134–185 km) (10–15 days). For the truly adventurous, this marathon trip offers a scenic yet little seen section of Big Bend country. Although not inside park boundaries, this section of the Rio Grande (69 mi / 111 km of which is designated by the government as Wild & Scenic River) is administered by Big Bend National Park. This trip requires lots of preparation: the take-outs require permission, some sections may need to portaged, special camping restrictions exist, and release forms must be filled out for this trip (not to mention the logistics of food, water, and shuttling) — beginners should definitely consider going with a tour operator. The put-in is at Heath Canyon near La Linda, Mexico (see the Boquillas Canyon entry) and there are multiple take-outs — Dryden Crossing (south of Dryden, TX) or Foster's Ranch (between Dryden and Langtry, TX) are the most common and both are on private land.

Hiking

Hiking is one of the best ways to experience Big Bend National Park; many sights are not accessible by any other method. Try to work in at least one trail from each of the environments — desert, mountain, and river — to get the full scope of what the park has to offer. For those short on time or of limited mobility, try one of several short "nature trails", such as the Window View, Chihuahuan Desert, and Rio Grande Village trails. For something a bit more involved, the Lost Mine and Window Trails are very popular (allow 3–4 hours), as is the Santa Elena Canyon Trail. Although a bit trickier to reach, the Grapevine, Pine Canyon, and Ernst Tinaja Trails are also popular desert treks.

Trail maps and topographical maps (for backcountry hiking) can be purchased at any visitor center. For $1 or less, certain popular trails have detailed booklets that can be purchased from visitor centers or little boxes near the trail-head. The paths of some desert hikes are marked by rock cairns (piles). Most of the trails offer minimal to no shade, so dress smartly and always bring plenty of water!

Chisos Basin

- Window View Trail. Easy (0.3 mi / 0.5 km round-trip). Flat, paved and wheelchair-accessible. A good, short introductory hike that also offers nice sunset views. The trail-head can be found at the Chisos Basin Lodge, facing the Window.

- Basin Loop Trail. Easy to Moderate (1.6 mi / 2.6 km round-trip). A good mountain hike if you don't have the time (or the wherewithal) for the others; this trail hikes up into a meadow with good views of the surrounding mountains. Begin at the main Chisos Basin Trail-head (somewhat behind some motel units, facing south) and either stay on the Laguna Meadow Trail or take the Pinnacles Trail turn-off; either way, continue on until you see the signs for the Basin Loop.

- Window Trail. Moderate (There are two trail-heads: from the Chisos Basin Lodge it is 5.6 mi / 9.0 km round-trip; from the Basin Campground - Site 52, it is 4.4 mi / 7.0 km round-trip). Among the more popular trails; it descends to a gap in the Chisos Basin Mountains — the Window — revealing stupendous views down to the desert far below, framed by enormous cliffs. There is some rock-scrambling in the final stretch and you may get your feet wet, but the most fascinating terrain is also in this last third. The trail ends at the very bottom of the Window: an exquisitely carved water pour-off that free-falls thousands of feet to the desert below (watch your step!). You may notice a sign for a turn-off for the Oak Creek Trail near the end; if you still have energy on the way back, follow it up about 0.25 mi (0.4 km) for an awesome vantage point above the Window. Keep in mind the descent is much easier and quicker than the return trip, which is all uphill. Hiking this trail may not be safe during or after a rain; even a seemingly small amount of rushing water can sweep you off.

- Lost Mine Trail. Moderate (4.8 mi / 7.7 km round-trip). Constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s and called "possibly the premier dayhike in the Chisos" by the park, the Lost Mine Trail trail climbs along ridges and switchbacks part-way up Lost Mine Peak, offering spectacular views of the surrounding mountains, canyons, and desert along the way. The first 1/3 of the hike may seem a bit grueling to average hikers, but stick with it at least that far to enjoy the first of the great views — or you can turn around about this point to make it a good short hike. The trail becomes rougher as you near the final portions and eventually even requires a bit of rock scrambling — but those who proceed are rewarded with the highest and greatest views. The trail-head is on a marked pull-off on the road towards the Chisos Mountain Lodge; parking can fill up even when the park is only moderately busy, so arrive early to beat the crowds.

- Emory Peak Trail. Strenuous (9.0 mi / 14.5 km round-trip). Leads to the highest point in Big Bend National Park with (of course) spectacular views as your reward. The trail-head begins at the Chisos Basin Trail-head (somewhat behind some motel units, facing south) — from there, take the Pinnacle Trails up 3.5 mi (5.6 km), at which point you'll see the side trail to Emory Peak. The last part requires a rock-scramble up a steep wall, but is well worth it — you've come this far, haven't you?

- The South Rim. Strenuous (~12 mi / ~19 km round-trip). The South Rim is somewhat of a classic for hikers ready to take it to the next level; this trail leads to wide, stunning views down to the desert and miles beyond into Mexico. Although it can be done in a day if you're fit and start early, it's best as a 1-night backpacking trek. Start at the Chisos Basin Trail-head (somewhat behind some motel units, facing south) — there are multiple route options from here: stay on the Laguna Meadow Trail or take the Pinnacles Trail turn-off (both are the endpoints of the same huge loop). If you have the time and stamina, you can also add the Emory Peak Trail to your itinerary since it's along the way (add 2 mi / 3 km total, half of it purely vertical). Another option is to explore the East Rim Trail sections to get the full Rim experience (tack on an extra 3.3 mi / 5.3 km total). The turn-offs are marked along the way on the main trail; however, know that a portion of the East Rim Trail (the Southeast Rim Trail) is closed to hiking during the peregrine falcon breeding season (February 1 to July 15). There are also numerous side trails that can either serve as a shortcut or take you off the trail and down into the desert, so bring a map.

North desert

- Panther Path. Easy (0.1 mi / 0.2 km round-trip). A pleasant, short hike in front of the Panther Junction visitor center among the desert flora.

- Grapevine Hills Trail. Easy (2.2 mi / 3.5 km round-trip). One of the most popular desert trails, it features a crowd-pleasing balanced-rock formation at the very end (you may have even seen it in various Texas guidebooks and brochures). Requires driving a dirt road to the trail-head, but is usually passable even for sedans (although expect very slow, rough going). Take the Grapevine Hills Road turn-off 3.3 mi (5 km) west of Panther Junction and follow it for about 7 mi (11 km).

- Dog Canyon Trail. Moderate (4.0 mi / 6.4 km round-trip). A backcountry trail through abundant desert wildlife that leads into Dog Canyon. About 3.5 mi (6 km) south of the Persimmon Gap Visitor Center is an exhibit for Dog Canyon that serves as the trail-head, you'll be able to see canyon in the distance as a notch in the hills. Requires some path-finding; be sure to inquire at the park first and you may want a map for the way back, if nothing else.

- Devil's Den. Moderate to Strenuous (6.0 mi / 9.6 km round-trip). This actually shares the same trail-head and part of the path with Dog Canyon Trail. About 1.5 mi (2.4 km) in there will be a fork in the trail and a sign that will point the way through some washes to intriguing, rock-strewn Devil's Den. Traditionally the trail climbs to the cliffs above, offering views down into the Den, but if you're fit and prepared for rock scrambling, climbing, and wading in waist-deep water, it's possible to hike back through it. Be sure to notify others of your plans and have at least one buddy - it's possible to get trapped by a wall that's too high to climb or a drop-off that's too steep. Path-finding is required; be sure to inquire at the park first and bring a map.

West desert

- Tuff Canyon Trail. Easy (0.75 mi / 1.2 km round-trip). Take the well-marked turn-off before Castolon (headed towards Santa Elena Canyon). There are viewpoints here but you can also hike down into the canyon; just follow the signs. For some reason gnats can be extra pesky in this area.

- Bottom of the Burro Mesa Pour-Off Trail. Easy (1.0 mi / 1.6 km round-trip). You'll see a turn-off for the Burro Mesa Pour-Off between the Sotol Vista Overlook and the Mule Ears Viewpoint along the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive. Follow the road 1.5 mi (2 km) to get to the trail-head. Requires a bit of path finding — rock cairns mark which way to go through the washes. Along the way you'll notice a giant rock formation that looks quite like a sideways sandwich and of course the enormous pour-off at the end. A different trail will take you to the top (see separate entry).

- Santa Elena Canyon Trail. Easy to Moderate (1.7 mi / 2.7 km round-trip). Among the more popular trails — a definite must-see. Follow the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive to the end, past Castolon. Near the parking area you can get great views of the canyon but to get the best views, cross Terlingua Creek towards the right-hand wall of the canyon. You'll likely see other people making their way to the trail; follow them if you're confused. It is possible for the creek to become too high to cross; if there's any doubt at all, hike the trail another time. The trail involves climbing up several switchbacks with stairs built into the canyon wall before descending to the banks of the Rio Grande, where the trail eventually ends.

- Red Rocks (Blue Creek) Canyon. Moderate (3.0 mi / 4.8 km round-trip). A scenic trail past the Homer Wilson Ranch house and through a large canyon; the eponymous red rocks can be seen at the end. The trail continues after that very steeply up into the Chisos Basin but this is only for hardcore backpackers. The trail-head is at the Blue Creek Ranch Overlook turn-off from the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive.

- Upper Burro Mesa Pour-Off Trail. Moderate (3.6 mi / 5.8 km round-trip). An adventurous trail that leads to the top of the Burro Mesa Pour-Off through some washes and a (somewhat spooky) slot canyon (a different trail will take you to the bottom — see separate entry). The trail-head is found 6.9 mi (11 km) south of the beginning of the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive. Parts of the trail are marked by rock cairns and are fairly easy to follow &emdash; that is unless a flood washes them away, in which case some path-finding (with a map and compass) will be required. Inquire about park conditions before setting out, also a good amount of rock-scrambling is required. Do not attempt if rain is in the forecast; some sections have no escape routes.

- Ward Spring Trail. Moderate (3.6 mi / 5.8 km round-trip). A good trail to find solitude; this route leads through the desert to a pleasant spring. The trail-head can be found at mile-marker 5.5 along the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive. Requires some path-finding.

- Mule Ears Spring Trail. Moderate (3.8 mi / 6.1 km round-trip). A trail that leads to a peaceful spring with expansive views of the Mule Ears formation and desert wildlife along the way. You can turn back after the spring or continue a bit further (and upwards) to get seldom-seen views of the other side of the Mule Ears. The trail-head starts at the well-marked Mule Ears Overlook turn-off along the Maxwell Scenic Drive.

- The Chimneys Trail. Moderate to Strenuous (4.8 mi / 7.7 km round-trip). Leads to a series of "chimneys"; rock pinnacles formed through volcanic activity and intriguingly decorated with Indian pictographs. The trail actually continues far past the chimneys and eventually leads to the unpaved Old Maverick Road which becomes an extremely long hike, instead just go back the way you came after visiting the chimneys. The trail-head is marked, about 1.2 mi (2 km) south of the Burro Mesa Pour-Off turnoff on the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive.

East desert

- Chihuahuan Desert Nature Trail. Easy (0.5 mi / 0.8 km round-trip). A pleasant jaunt through a particularly lush section of desert; a windmill is nearby. It's at the end of the Dugout Wells turn-off, about 5 mi east of Panther Junction.

- Rio Grande Village Natural Trail. Easy (0.75 mi / 1.2 km round-trip). Short and easy; an excellent showcase of one of Big Bend's 3 major ecosystems — the river. Another good place for sunset views. The trail-head is past the Rio Grande Village visitor center; make your way to the southeast corner and find campsite #18 (there should be signs). May be temporarily closed if there has been recent heavy flooding.

- Boquillas Canyon Trail. Easy (1.4 mi / 2.2 km round-trip). A great, relatively short and easy hike that goes into the mouth of Boquillas Canyon. There is a short hike up a hill and then a descent towards the river and the canyon, through sand and lots of rocks (trail may be washed out after flooding; no problem, just find your own trail towards the canyon). Although impressive, it is perhaps less wow-inducing than the more popular Santa Elena Canyon (but also less crowded) so you may want to consider hiking this trail first if you plan on doing both. On the road towards Rio Grande Village, there will be a well-marked side-road that leads to the trail-head.

- Ernst Tinaja. Easy (1.4 mi / 2.2 km round-trip). Another relatively short and easy hike that takes you on a scenic journey to a large tinaja; a large natural hole in the rocks that holds water. This is definitely a great hike to take if you can make it to the trail-head; a high-clearance vehicle is required. On the way to the Rio Grande Village there will be a well-marked turn-off for Old Ore Road (unpaved), take it and drive until you see the Ernst Tinaja turn-off (there is also a primitive campsite there) — this is the fastest route.

- Hot Springs Canyon Trail. Easy to Moderate depending on trail-head (1.0 mi / 1.6 km round-trip from Hot Springs Road or 3.0 mi / 4.8 km round-trip from Rio Grande Village). A pretty trail that shadows the Rio Grande to the historic village of Hot Springs, where you'll find several abandoned ruins along with the springs themselves. There are also Indian pictographs and side-trails to other springs nearby. There are two trail-heads; one at either end of the trail with the Springs in between. The shorter is at the end of Hot Springs Road and is preferred if you are more interested in the springs than the hike. The trail-head for the longer hike is in the Rio Grande Village area (look for the Daniels Ranch); it can get particularly hot in the warmer months.

- Pine Canyon Trail. Moderate (4.0 mi / 6.4 km round-trip). A scenic, moderately difficult hike that leads from the desert to Pine Canyon where, if there's been any rain, you'll find the crowd-pleasing Pine Canyon Falls. A high-clearance vehicle is required to reach trail-head; on the main road towards Rio Grande Village there will be a well-marked turn-off for Glenn Spring Road. Follow it until you reach the junction with Pine Canyon Road, then follow it to the end to get to the trail-head. The falls themselves are at the edge of the Chisos which run the small risk of bears and mountain lions.

- Ore Terminal Trail. Strenuous (8.0 mi / 12.9 km round-trip). A tough trail through isolated desert scenery that showcases many impressive old mining ruins along the way. The marked trail-head can be found along the Boquillas Canyon road, near the Boquillas Canyon Overlook turn-off (the Marufo Vega trail-head is also found here). Path-finding required.

- Marufo Vega Trail. Strenuous (14.0 mi / 22.5 km round-trip). An even tougher trail through truly breathtaking desert scenery. The marked trail-head can be found along the Boquillas Canyon road, near the Boquillas Canyon Overlook turn-off (the Ore Terminal trail-head is also found here). As with any long desert trail, it's a bad — and potentially deadly — idea to hike it in the summer. Lots of path-finding is required — see here and inquire at the park before undertaking.

Other desert hikes

- Elephant Tusk Trail. Strenuous (17 mi / 27.3 km round trip). Trail begins across from the Elephant tusk campsite, crosses the desert floor, passes next to Elephant Tusk mountain, and the end links up with the Dodson trail (Outer Mountain Loop). Requires a high clearance vehicle if coming from the southern part of black gap road or a 4WD vehicle if coming from the northern part. Very remote and very rugged terrain means you'll probably be the only human for miles, but be rewarded with spectacular views of the desert, mountain rim, and even the Rio Grande on a clear day. Theoretically, it is possible to climb Elephant tusk mountain but one would have to go off trail and run a high risk of losing it entirely. The first the 4-4½ miles are poorly marked by metal rods every 200 ft, and eventually just drops off entirely requiring lots of path finding. Like the Mesa de Anguilla, the Elephant Tusk trail does not show up on all park maps, so plan accordingly.

- Mariscal Canyon Rim Trail. Strenuous (6.6 mi / 10.7 km round-trip). Requires a high-clearance vehicle to reach the trail-head (take the Talley Road spur off of the River Road), which is on the remote, extreme south-side of the park. You'll encounter very rugged terrain but with superlative views of the canyon (and likely plenty of solitude) as your reward; lots of path-finding is required.

- The Mesa de Anguila. Moderate to Strenuous. Very rugged, remote, and primitive, with expansive views from the extreme southwest-side of the park. There are several possible routes and trail-heads; the most commonly used one is accessed from nearby Lajitas, behind the golf course (the resort there also offers a guided tour for guests along a section of the trail). Lots of path-finding is required; this trail is not even marked on park maps due to the potential for inexperienced hikers getting in over their heads — see here and inquire at the park before attempting.

- Outer Mountain Loop. Strenuous (30.0 mi / 48.2 km round-trip). A somewhat notorious trek for the hardcore backpacker, involving hiking through the desert up into the Chisos Basin mountains and then back down into the desert again, forming a huge loop. Trails involved include Blue Creek Canyon, parts of the South Rim trails, Juniper Canyon, and the Dodson Trail. It's rugged and extremely challenging — and perhaps even impossible to hike safely in the summer. Preparation is a must; see here and inquire at the park before undertaking.

Soaking in the Hot Springs

A reminder of the park's past volcanic turmoil, the Langford Hot Springs (or just "hot springs"; everyone will know what you're talking about) is a small, jacuzzi-sized pool of naturally occurring 105°F (41°C) water from deep below the earth. The spring had been long known locally for its supposed healing powers and became somewhat of a tourist site in the early 20th century due to the entrepreneurial efforts of J.O. Langford. All that's left is the foundations, but it still makes for a fine place to soak after a long day (especially underneath the stars).

The springs lie in the southeastern region of the park off of TX-118 near Rio Grande Village. There are two ways to reach it: Hot Springs Road or the Hot Springs Canyon Trail; both involve at least some hiking, so be sure to come dressed appropriately. The springs are literally right next to the Rio Grande and can be completely engulfed by the river if it floods, filling it with sand and other debris. The spring waters contain several trace elements from its source underground — although the healing powers of the spring are often attributed to this fact, it is probably best not to drink any and some even find that their skin is sensitive to it.

Visit Mexico

After a long closure, the Boquillas Crossing has reopened for day-trips to the Mexican village of Boquillas del Carmen. The old mining village has long been a destination for American visitors, but endured a border closure between 2002 and 2013 as a result of increased security concerns after the September 11 attacks. Fortunately, however, the crossing reopened in April 2013 with a remote connection to a US Border Patrol post in El Paso, and the once-dying town is again thriving with American tourist dollars and Mexican government investment. Bring your passport and American cash in small bills, and you can cross the river on a rowboat (the "international ferry"), where an English-speaking guide will show you the town. (You can skip the rowboat and wade across the Rio "Grande", but your dollars help the town's economy, so it's good form to pay.)

The Boquillas Crossing is between Rio Grande Village and Boquillas Canyon. In addition to your passport, be sure to bring cash. The ferry costs $5 round trip (tourists sometimes choose to wade across the river, but they do so at their own risk). You can walk the 0.75-mile to town, or you can ride a burro for $5 round trip. In town, local handicrafts can be had for about $6 each and a delicious lunch for $10-15 at either of the restaurants. Your guide works for tips, and depending on how much you do with them, expect to tip somewhere in the neighborhood of $10-35.

The crossing is open Wednesday-Sunday year-round from 9AM-6PM, but may close at 5PM December-January, and you are advised to return 30 minutes before closing.

Other activities

- Fishing is permitted, but only in the Rio Grande; you'll need a free permit first, which you can get at any visitor center. Live bait is not allowed; other types of bait can be purchased at the Rio Grande Village Store. Expect mostly catfish and, rarely, garfish.

- Rock climbing is not practiced, despite Big Bend's ample supply of rocks; they are just too unstable.

- Stargazing is very popular; the skies in the Big Bend region are among the clearest in the U.S. due to the absence of light pollution (no wonder the McDonald Observatory was built near nearby Fort Davis!). Simply sitting out and gazing up at the sky on a clear night is enough to astound many city folks, but bring a telescope for the best views. There are also occasional ranger-led stargazing parties; inquire at the park for schedules.

- Swimming and wading are also highly discouraged, whether in the river or any other natural water source in the park.

Tour operators and outfitters

For Big Bend novices or anyone who doesn't want to deal with the hassle, try going with a local tour operator. They each have years of experience and not only love their jobs, but also the Big Bend region. They can show you places and give you factual tidbits that only locals would know. For tours, it's good to inquire ahead as far in advance as possible, especially about what supplies they provide (safety equipment and meals are a definite) but also what you should bring along. Not only can tours be arranged but also equipment rentals and shuttle services to just about any destination, for those with an independent streak.

- Big Bend River Tours. The oldest tour operator; they offer guided river (natch), hiking, and backroad tours. They also have fun specials on river trips during holidays and other times of the year.

- Desert Sports. Desert Sports offers guided river and hiking trips and are unique in that they also specialize in nifty mountain bike tours, rental, and repair.

- Far Flung Outdoor Center. This company offers guided river trips and jeep tours (and ATV tours, but not in the park due to restricted use). They also offer specialty river tours, which may include gourmet dining, wine tasting, live local music, family tours, stargazing and more.

- Lone Star Trekking, +1 979-393-8022. Lone Star Trekking provides four and five day guided backpacking trips throughout the park. The company provides all gear, equipment and food.

- The resort at Lajitas also offers various guided tours through the park via Red Rock Outfitters (among many other activities), although the services are provided to guests only.

In addition, the park provides daily ranger-led programs for free, which can include a variety of activities and topics. The schedule is constantly changing and usually you're required to bring a flashlight (one can be purchased at the park if need be). You can also hire a park ranger for a personal tour, although you must arrange transportation yourself. The going rate is $35/hour with a 4-hour minimum and reservations must be made in advance at +1 432 477-1108 .

Buy

Park-related books and knick-knacks can be purchased from all visitor centers. Supplies and groceries, though available, are often limited in selection. The nearest town with chain retailers is Alpine.

- Chisos Basin Store, 29.2703°, -103.3006°, +1 432 477-2291. 8AM-9PM daily. Here you'll find a camp store with supplies and groceries, an ATM, and a dedicated gift shop with gourmet condiments and local arts and crafts.

- Rio Grande Village Store, 29.1825°, -102.9614°, +1 432 477-2293. 9AM-6PM daily. Carries supplies, groceries, and gifts. Coin-operated showers and laundry and an ATM are also nearby.

Gasoline

Expect gas in the area to be pricier than the national average. Always remember to fill up before setting out as distances between services are large.

- Panther Junction Service Station, 29.3294°, -103.2088°, +1 432 477-2294. 7AM-7PM daily. Sells gas (including diesel), limited groceries, and can even do minor repairs. With a Visa or Mastercard, fuel is available 24 hours a day.

- Rio Grande Village Service Station, 29.1827°, -102.9613°, +1 432 477-2293. 9AM-6PM daily. Sells gas, diesel, and propane and is in the same area as the Rio Grande Village Store - in fact, gas is purchased inside the store.

Outside of the park

- Stillwell Store, 29.6442°, -103.079°, +1 432 376-2244, info@stillwellstore.com. 8AM-9PM daily. Sells groceries, supplies, and gas (but not diesel).

Gas and limited supplies can also be purchased from Study Butte-Terlingua, just outside the western entrance of the park.

Eat

- Chisos Mountains Lodge Restaurant, Chisos Mountains Lodge (in the Chisos Basin developed area; see under Sleep section), NA°, NA°, +1 432 477-2292. 7AM-9PM daily. Serves up surprisingly decent Tex-Mex and comfort food with what may be arguably the best view from any building in the park. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are available, as well as wine; they also have a soup and salad bar. They even offer a take-out lunch for hikes or picnics. Try the "Texas Toothpicks" (battered and fried strings of onion and jalapeños with dipping sauce). $8-20

Just outside of the park there are dining options in nearby Study Butte-Terlingua and Lajitas.

Drink

There are no bars as such in the park, however alcoholic beverages can be purchased at the Chisos Mountains Lodge Restaurant, the Chisos Basin Store, La Harmonia Store, and the Rio Grande Village Store. However, open alcoholic beverages are not permitted on their premises (except for inside the restaurant) or their parking lots. They are similarly not permitted at visitor centers or in the Langford Hot Springs area.

Outside of the park, there is at least one bar in the nearby Study Butte-Terlingua area.

Sleep

Lodging and campsites are literally packed during the busy season (Thanksgiving, Christmas, or New Year's weekend, and during Spring Break) — all but the most remote backcountry camp sites are filled up. Reserve ahead as far in advance as possible (at least several months beforehand) if you plan on staying during that time.

Camping at developed sites or in the backcountry is limited to 14 consecutive days, with a maximum of 28 days in any given year (but no more than 14 nights in any given site). Wood and ground fires are not permitted in the park, as they would totally wreak havoc in this parched desert ecosystem. Be mindful of cigarettes and any portable heat sources, such as grills.

Lodging

The Stillwell Store, just outside of the park's north entrance, offers full RV-hookups or cheap primitive camping (with amenities on-site); expect to pay around from $5 for a primitive campsite up to $19 for an RV hook-up.

While there is only one hotel option within the park (see below), there are several nice lodging options in the nearby Study Butte-Terlingua area, including some secluded getaways, as well as luxury accommodations in Lajitas (the poshest place to stay in the area); all of which are relatively very close to the park.

If you don't mind the drive, your lodging options expand even more if you consider staying in the larger towns of Marathon, Alpine, Presidio, Marfa, or Fort Davis. Expect to add at least an extra hour of driving time one-way if basing yourself in one of these locations (except Marathon, which is about a 40-50 minute drive).

- Chisos Mountains Lodge, Basin Rural Station (in the Chisos Basin developed area), 29.2705°, -103.2993°, +1 432 477-2291. Check-in: 4PM, check-out: 11AM. The only hotel option within the park borders offers convenience as well as mind-blowing views, this can't be beat. Although far from luxurious, you are basically at the hub of park activity with numerous guest services just steps away. Various motel-style units are available (the "Casa Grande" rooms are newest), as well as pricier stone cottages that can sleep up to 6. TVs are not included but can be rented for about $10 (with a choice of 2 DVDs) — but why would you need one? The Lodge, along with the restaurant, are not operated by the park but rather by concessioner Forever Resorts, Inc. $119-147

Developed campgrounds

Traditional "family style" campsites are available for a self-pay fee of $14/night. During the "reservation season" (Nov 15-Apr 15), a limited number of these sites are reservable (up to 180 days in advance) — 26 at Chisos Basin and 43 at Rio Grande Village, with a limit of 8 people per campsite. For groups of 9 or more, there are a very limited number of designated "group" campsites at all three locations; these are by reservation only (up to 360 days in advance) and with a rate of $3/night. Those with a Senior Pass or Access Pass get a 50% discount on camping fees.