Dagestan - republic of Russia

Travel to Dagestan is unsafe due to political instability, criminal activity, bombings, Islamist terrorist attacks, and crime. Many governments recommend against any travel to Dagestan.

Dagestan (Russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н; Avar: Магӏарухъ Жумхӏурият) is the most culturally diverse republic in the Caucasus, and at the Caspian Gates between Persia and Europe has been of historic significance since antiquity. Plagued by a decade of conflict since the turn of the century, Dagestan has been a safe and attractive travel destination off the beaten path for several years. Sandy beaches along the Caspian coast and the rural wilderness of the majestic Caucasian mountains await in this region not yet overrun by mass tourism.

It is a republic of the Russian Federation in the North Caucasus bordering Chechnya and Georgia to the west, Stavropol Krai and Kalmykia to the north, the Caspian Sea to the east, and Azerbaijan to the south.

Settlements

Cities

- Makhachkala — capital and largest city, a fast-growing multi-ethnic metropolis on the shores of the Caspian Sea

- Buynaksk — in central Dagestan in the foothills of the Greater Caucasus Mountains

- Derbent — walled city and on the Caspian in southern Dagestan; one of the most impressive historical sites in Russia

- Izberbash — a popular beach resort

- Khasavyurt — a relatively large city (for the region) near the border with Chechnya

- Kaspiysk — known for its naval base that is home to hovercraft and ekranoplans, and Caspian Sea Monster

- Kizlyar — famous for its grape vodka, cognac, and traditional blacksmithing guild

- Yuzhno-Sukhokumsk — a city located is northwest Dagestan

Towns and villages

- Akhty — a majestically set mountain aul with more tourist facilities than any other

- Gimri — a small mountain village in the eastern (and therefore easiest to get to) section of Dagestan's mountainous region, with more history on view than in most villages.

- Gunib — mountain town with a historic fortress and lake

- Kubachi — a mountain town famous for the Persian pottery named after it

- Tindi — a small picturesque aul with a historic minaret in the mountains of southwestern Dagestan, near the Georgian and Chechen borders; probably not a safe area for travel

Other destinations

- Kizlyar Bay — a marshy bay of the Caspian Sea, a bird watcher's paradise, part of the Dagestansky Nature Reserve

- Sulak Canyon 📍 – spectacular canyon, among the deepest in the world, and suitable for rafting. It is often referred to as the Grand Canyon of the Caucasus. The Chirkey Dam with a height of 232.5 m is the tallest arch dam in the Russian Federation, holding back a 42 km² lake upstream from the canyon.

- Karadakhskaya Tesnina 📍 — deep gorge with steep cliffs and half a dozen waterfalls along the way, the gorge itself is about 5 km long but continues with a trekking path all the way to Gunib.

Understand

Dagestan shares with its Caucasian neighbours the towering mountains of the Greater Caucasus, rushing Caucasian rivers, and spectacularly situated stone auls, mountaintop villages. But in an already diverse region, Dagestan is a wonderland of ethnic and cultural diversity. About 35 separate ethnolinguistic groups live in this Scotland-sized republic and the region contains an amazing 12 language families. For all this cultural diversity, Dagestanis are fairly united in their Islamic religion — virtually all non-Russian ethnic groups are Muslim. This is probably true since almost 32,000 people have left in a mass exit from Dagestan since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those people were the Mountain Jews, Juhuro, who spoke Persian or one of its dialects.

Get in

Makhachkala will almost certainly be your first destination, whether by plane from Moscow, or by train via Rostov-on-Don through Mineralnye Vody.

Get around

Marshrutkas are the standard way of getting around the region, and will take you most anywhere you intend to go. The twice-daily train between Makhachkala and Derbent is also a good option.

Driving or hiking the mountainous regions would be a fantastic way to travel between villages and to enjoy Dagestan's striking natural beauty.

Talk

Within the seven language families of the Dagestanian language grouping (unrelated except by geography) alone there are about 30 languages, many of them considered among the most difficult in the world to master. Fortunately, everyone, regardless of nationality, understands the lingua franca, Russian. The indigenous Avarski language, spoken by the Avar, is the second lingua franca of the region. Azeri is also widely used in the southeast Caspian region around Derbent; those who speak Turkish may be able to make themselves understood in this area. However, English is spoken by almost nobody, even in Makhachkala. Getting around is nearly impossible without at least understanding some basic Russian.

Because English is rarely heard anywhere in Dagestan, the language immediately attracts attention on the street. In cities such as Makhachkala and Derbent this will be met with curiosity from locals who only rarely encounter tourists, however in the mountain wilderness near the border with Chechnya this attention could be unwanted. See the Stay safe section for more details.

The five indigenous literary languages (and therefore the most rewarding to study) are the aforementioned Avarski, as well as Lak, Dargwa, Lezgian, and Tabasaran. Avar is the most widespread, and there is an Avar Theater in Makhachkala devoted to performances of works in the language.

See

Derbent has Dagestan's main attraction in its ancient walled city, a , and the single most important historical attraction in all of the Caucasus.

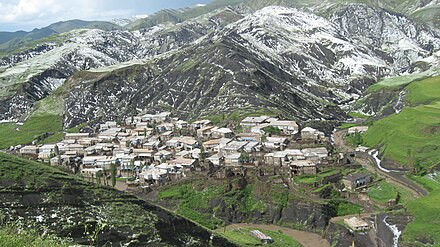

The mountains of southern and southwestern Dagestan, the high peaks of the Greater Caucasus, should be a principal attraction. Mountains topped with auls, small villages filled with stone houses and home to famed chivalric mountain tribes are as fascinating culturally as they are beautiful.

If you'd like to catch a glimpse of Dagestani culture and beauty, check online for a copy of the late Sergei Bodrov's haunting film, Prisoner of the Mountains (Кавказский пленник), which was shot in a Dagestani mountain aul, hiring the villagers as extras.

Culture and history

- Khunzakhskaya Krepost (Хунзахская крепость), 42.5566298°, 46.7221901°. Ancient fortress near Khunzakh. 2021-03-09

- Akhoulgo Historical Complex (Мемориальный комплекс общей памяти и общей судьбы "Ахульго"), улица Имама Газимагомеда 1/1, 42.77481°, 46.73897°, +7 8 988 645 1608. M-F 08:00-17:00. Brand new reconstruction of a historical watchtower featuring a museum and observation platform with a magnificent view over the surrounding hills. Opened in 2017, it should be on everyone's itinerary. 2021-03-09

- Datuna Church (Датунский храм Хв.), 42.47034°, 46.62088°. Georgian Orthodox church built in the 9th century, it was hidden in the mountains 300 m upstream of a narrow gorge to keep it hidden from the invading Mongol army in the 12th century. It is exceptionally well preserved and one of the oldest surviving religious buildings in Dagestan. There is no road to it, so hiking shoes are a must! Free 2021-03-09

- Gamzat Tsadasa Memorial Literature Museum (Музей имени Гамзата Цадаса), Tsada 7, 42.57149°, 46.71140°. Literature museum dedicated to Gamzat Tsadasa, one of the great poets of the Avar language. 2021-03-09

- Towers of Goor, 42.4338°, 46.5614°. 24/7. Historic towers built into the mountain flank, offering fantastic views. A trek of intermediate difficulty. Requires an off-road vehicle to get there, but otherwise highly recommended. Kakhib is not far away, so can be combined for a day trip. The nearest city, Gunib, is ca. 2.5 hours away. Free 2021-03-09

- Kakhib, 42.42854°, 46.59973°. Ruins of a 18th century aul, some 2.5 hours from Gunib, and best explored with a guide. Kakhib's towers are built into the sides of steep cliffs, and the perfect destination for a hiking day. The towers of Goor are also close by.

- Centre of Traditional National Culture, Shkolnaya St., 2A, Madzhalis 368590, 42.12529°, 47.83538°, +7 963 799-66-57. Interactive museum with demonstrations and exhibitions on embroidery and traditional Kaytag arts. The collection includes household items, arts, crafts, music instruments, traditional clothes, photographs, books, and so on. At the end of the guided tour it's possible to dress up in traditional clothing for a photo shoot. 2021-03-09

- Khunzakh Museum of History and Local Lore (Хунзахский историко-краеведческий музей), Хунзахская улица, 22, Khunzakh 368260, 42.53794°, 46.70286°, +7 988 697 6716. Tu-Sa 09:00-17:00. One of the largest museums in Dagestan since 1975. It features exhibits reflecting the nature, history and life of the region, military and labour traditions of the highlanders, and the role of the Khunzakh people in the Caucasian, Civil and Second World War. The museum also has a significant collection of ceramics, silver and wood products, rare weapons, manuscripts, household items and tools of the mountaineers. It is housed in a 19th century building that is an architectural monument in itself. adults , children 2021-03-09

Nature

- Irganayskoye Reservoir 📍 — mountain lake with turquoise waters, a serene and peaceful atmosphere, not yet overrun by tourists

- Sarykum Sand Dune, one of the largest sand dunes in Eurasia, part of the Sarykumskye Barchany dune area and the Dagestansky Nature Reserve

- Tobot Waterfall 📍 — majestic waterfall surrounded by pristine nature. Near Khunzakh.

Do

Most activities of any interest indoors, mainly cultural performances and sporting events, are to be found in Makhachkala.

Buy

- Famed Dagestani rugs

- Beluga caviar

- Traditional swords and daggers of the various ethnic groups

- Traditional hats and costumes

Eat

Dagestan is renowned for its delicious local dishes: hinkal (a tasty pasta/dough-like entity served with garlic sauce and some kind of meat, usually young, boiled lamb), chudu (a quesadilla-like thin dough with special meats, cheeses or vegetables inside), and shashlik (roast shishkabab, usually lamb meat).

There are countless cafes serving Dagestani and Russian foods. A few, newer Chinese and Japanese restaurants have opened, but the food lacks authenticity and flavour. Western foods are likewise a scarcity, and there are no Western food chains anywhere in Dagestan. And don't be fooled by the many advertisements for 'pizza' — even by typical Russian standards, the pizzas lack the most basic ingredients of pizza: sauce, cheeses, etc. The closest you'll come to finding a real steak will be at the new El Gusto Cafe close the centre of Makhachkala, a delightful restaurant where you can find a few other Western dishes satisfactorily prepared.

Drink

You will have no problem getting a drink, be it in a house in a mountain aul or a cafe/bar in Derbent.

Sleep

The best developed lodging facilities (still pretty basic) are in Makhachkala and Derbent, but you should be able to find guesthouse with little difficulty in any town or village. The Dagestani peoples still retain their legendary chivalric hospitality, and will go out of their ways to find you a place to stay.

Learn

- Dagestan State University (Дагестанский государственный университет). Founded in 1931, it is the principal institute of higher education in the republic. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan Scientific Research Institute of Agriculture. Specialised in agriculture, fishery, and forestry. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Дагестанский федеральный исследовательский центр РАН). Since 1945 this has been the Dagestani division of the Soviet, and later Russian Academy of Sciences. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan State Pedagogical University (Дагестанский государственный педагогический университет). Prestigious university, received the Honorary Diploma of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR in 1967 for excellence in its field. 2021-03-02

- Institute of Physics. Theoretical and applied nuclear and physics research. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan State Agricultural Academy (Дагестанский государственный аграрный университет), 42.9945°, 47.4733°. Agricultural sciences. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan State Institute of National Economy. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union and departure from a centralised economy planned in Moscow, the State Institute of National Economy has been in charge of economic growth in the republic since 1991. 2021-03-02

- Dagestan State Technical University — located in Makhachkala

- Dagestan State Medical Academy, Makhachkala (formerly known as Dagestan State Medical Institute). Caters local and international students, mainly from southeast countries.

Work

Dagestan has one of the highest unemployment rates among the regions of the Russian Federation, although the situation here is better than in neighboring Chechnya or Ingushetia. Salaries are also low, and the population most often receives no more than $ 200-250 per month. Dagestanis themselves often move in search of a better life and to earn money in major cities of Russia.

Dagestan has one of the highest unemployment rates among the regions of the Russian Federation, although the situation here is better than in neighboring Chechnya or Ingushetia. Salaries are also low, and the population most often receives no more than $ 200-250 per month. Dagestanis themselves often move in search of a better life and to earn money in major cities of Russia.

Stay safe

As perhaps the most multi-ethnic and multi-cultural republic in the Russian Federation, Dagestan has had its share of violence in the late 1990s. It became internationally infamous as a hotspot of Islamic terrorism, extremism, corruption, crime, and instability. The security situation was a result of Islamic extremists in neighbouring Chechnya, which sporadically spilled over into Dagestan, Ingushetia, and other republics in the Caucasus in their attempts to establish an Islamic state in the region and implement Sharia law. Unlike in Chechnya, Islamic extremists struggled to establish a foothold in Dagestan, however. When some 3,000 Islamic fighters launched an invasion of Dagestan at the end of the 1990s, instead of being received as 'liberators', they met fierce resistance of the Dagestanis who did not welcome the invading extremists. With the help of Federal forces, the invaders were beaten back to Chechnya within a few weeks, and responded by launching guerilla attacks over the next decade. The conflict grew in complexity, with Chechen insurgents fighting a war of attrition with Dagestani law enforcement and Federal security forces. As time passed, the Salafist extremists became increasingly isolated as they also attacked the moderate Sufi Muslims in Dagestani communities for their difference in interpretation of the religion. Attacks against police stations and Russian officials were regular events throughout Dagestan until 2013.

This changed with the rise of ISIS in the Middle East, and after being unable to establish an Islamic Caliphate in the Caucasus after trying 15 years, many extremist cells relocated to Iraq or Syria to continue the fight. The Dagestani and Federal governments filled the vacuum by ramping up law enforcement efforts and rounding up remaining extremists cells. The strategy has been successful, and terrorist attacks have become a rare event in Dagestan since 2015. If/when they do take place, they are mostly aimed at government officials or police stations in the capital, and never target tourists or ordinary civilians. After the demise of ISIS, the Federal government has systematically repatriated surviving fighters and convicted them of terrorism activities which carry long prison sentences in the Russian Federation. The strategy was successful to keep radical extremists off the streets, and in combination with a change of leadership in Chechnya, has allowed peace to return to Dagestan since 2016-2017.

With that in mind, most of Dagestan is now a safe travel destination for foreign tourists. All of the major cities, including the entire Caspian Sea coastline (Makhachkala, Izberbash, Derbent, Kaspiysk) are very safe for travel. The situation is more nuanced in the mountainous regions where the terrain makes effective law enforcement difficult. The inaccessible mountains are an ideal hiding place for terrorist cells. Nonetheless there have been no reported terrorist attacks for many years. The Dagestani people are already culturally diverse, and are curious about tourists with foreign cultures visiting their country. They also understand the economic opportunities offered by tourism.

Crime levels are very low in the rural villages and towns, but slightly higher in the major cities. Theft and pickpocketing are common in the tourist areas and at beaches, although violent robberies are rare. When travelling inland, expect security checkpoints and random searches, so carry a copy of identity documents at all times. Security forces are generally helpful, but corruption is sky high in Dagestan, so bribes are occasionally expected to 'grease the gears' and speed up your passage. Officers will likely only speak Russian, so a short written summary of your travel itinerary in Russian will be helpful if you don't speak Russian. A local guide may make life considerably easier. It helps to have the phone number of your hotel or host family at hand.

Since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2022, unrest has again increased in Dagestan, as Russian security forces are distracted by the ongoing conflict. There is considerable opposition against the large-scale conscriptions that has have led to a disproportional fraction of young Dagestani men drafted into the army. Although protests thus far have not yet turned violent, it is wise to stay away from such events, and avoid bringing up the subject of conscription during conversations.

Stay healthy

Respect

As with the rest of the North Caucasus, Dagestan is a conservative and highly religious place. By applying a bit of common courtesy, you should have no problems getting around.

The civil war is still fresh in memory, and 25 years of political turmoil in the region has left the population divided. The security situation is a sensitive subject and should be avoided. The Dagestani peoples have a strong identity and resisted the 1999 Chechen invasion of their country, and do not want to be associated with any kind of extremism or terrorism. Likewise the extremists that left Dagestan to join ISIS in the Middle East is an extremely sensitive subject, and many Dagestani have been indirectly involved.

The role of the Russian federal security forces is another sensitive subject which has divided opinions. In larger cities, people are generally more supportive of the Russian military because terrorist attacks used to target government and security facilities in large cities. In the mountains, on the other hand, the Russian military has a poor reputation because of their strategies to end the civil war, which included blockades of entire towns and mass arrests. Depending on whom you ask, the Russians can be considered a peacekeeping or foreign occupation force. Soviet era naval base in the Caspian Sea, 3 km off the Kaspiysk coast, miserably rusting away since the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Finally, the Soviet era is a sensitive subject among the older Dagestani. To the traveller, it may appear as if much of the Soviet legacy consists of ugly concrete housing blocks, but those who lived in Dagestan when it was part of the Soviet Union remember it for its investments in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and perhaps most important of all: safety and security. The effect of the Soviet Union divides young and older generations in Dagestan. Soviet monuments (such as Lenin statues) and rusting infrastructure are a daily reminder of the Soviet days that many older Dagestani remember melancholically.

Connect

Mobile

In Dagestan there are four GSM operators (MTS, Beeline, Megafon, Dagestanskaya Sotovaya Svyaz') and two 3G-UMTS operators (Megafon, Beeline), and they often have offers that give you a SIM card for free or at least very cheap. If you are planning to stay a while and to keep in touch with Dagestani and other North-Caucasian peoples, then you should consider buying a local SIM card instead of going on roaming. If you buy a SIM card from a shop you'll need your passport for identification. It only takes five minutes to do the paperwork and it will cost less than US$10.

Embassies and consulates

There are no embassies or consular services in Dagestan. Most embassies and consulates are 1900 km away in Moscow.

Go next

Just across the border with Georgia is the breathtakingly gorgeous region of Tusheti, but the border is for all intents and purposes closed, so the route to Georgia becomes extremely long and indirect via plane.

The border with Azerbaijan is open, but it is reputedly a very bad experience. However, Northeastern Azerbaijan is a wonderful place for treks in forest covered mountains.

The most obvious next destination would be Chechnya, with its shared culture, proximity, and similarly beautiful mountainous landscapes.