Go

Go

For information on going somewhere, see Transport, and the Get in, Get around and Go next sections of the destination articles.

Go is the English name for an ancient board game called go (碁) or igo (囲碁) in Japanese, wéiqí (圍棋/围棋) in Chinese and baduk (바둑) in Korean.

Go is the world's second most played board game (after Xiangqi, Chinese chess) and, except perhaps for backgammon, it is the oldest board game still commonly played. It originated in China; the first written references are from the Spring and Autumn period (771-478 BCE) but the game is likely older. It reached Korea by the 5th century CE and Japan by the 7th. All three countries have books and game records that are centuries old and still studied.

The game is still most popular in East Asia, especially China, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, but it is now played all over the world. There are professional players and tournaments with prizes in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. In Asia, some of the pros get the sort of adulation that is paid to sports stars or media stars anywhere.

There is a wiki called Sensei's Library dedicated to the game, with many pages for beginners and links to many other resources. The web forum Life in 19x19 is quite active and also has a beginners' section.

Michael Redmond was the first Westerner (American) to reach the top (9 dan) rank in professional Go. His YouTube channel, Go TV, has many videos about the game. Redmond served as the English language commentator for a remarkable series of games which was televised live worldwide in 2016 with an estimated 80 million viewers. A computer program called AlphaGo beat one of the top human professionals four games out of five. This was the first completely unambiguous demonstration that Artificial Intelligence could play at that level, and came as a surprise to many. There is a documentary film, AlphaGo - The Movie about the program's development, culminating with this series of games.

There are many other resources in multiple languages; books and magazines, newspaper columns and TV shows, at least half a dozen other YouTube channels, many web sites, discussion groups on Facebook and Reddit, several web forums, and many online servers for playing the game.

Understand

The rules for Go are quite simple, about as complex as checkers. However playing well — both strategy and tactics — is at least as difficult as chess, arguably quite a bit more so. This section describes the basics of the rules and scoring and gives an introduction to the strategy and tactics.

Go is a game of complete information like chess or checkers; it does not have a random factor, such as what cards you are dealt or how the dice fall, and nothing is hidden. Like those games, it is also zero-sum; the usual outcome is victory for one player and defeat for the other. Games that do not give a win/loss result are possible but quite rare.

Go is a game of complete information like chess or checkers; it does not have a random factor, such as what cards you are dealt or how the dice fall, and nothing is hidden. Like those games, it is also zero-sum; the usual outcome is victory for one player and defeat for the other. Games that do not give a win/loss result are possible but quite rare.

The standard board size is 19 by 19 lines, but 13x13 or 9x9 are also used. Different countries, and different online servers, have slightly different sets of rules, scoring methods, and systems for ranking players, but they are all basically similar.

The game originated in China, but it was introduced to the West via Japan, so most English speakers use the Japanese names for the game itself and related terminology. English speakers in Singapore and Malaysia, though, use Chinese terms because the game was brought to that region by Chinese immigrants. This article uses the Japanese-derived terms.

Rules

Each player places one stone on the board per turn; pieces are placed on the intersections of lines, not inside the squares as in chess. Pieces never move, though they may be captured and taken off the board. A player may pass his or her turn if there is no advantage to be gained by placing a stone, and the game ends when both players pass in succession or when one player resigns.

The basic idea is to place stones efficiently so as to control more territory than the opponent. This is quite different from chess or xiangqi where the goal is to capture the king/general. It is quite common to give up something in one area of the board in return for an advantage elsewhere, and keen judgement of such matters is one of the traits that make a strong player. A proverb says Chess is a battle; Go is a war, and another view claims Go is a negotiation.

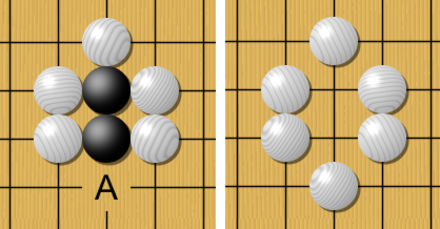

If a group of stones has no liberties (connections to empty intersections), then it is captured and its stones are taken off the board. The "before" part of the diagram shows a black group in atari; a white move at A would take its only liberty and kill the group. The "after" part shows the result of that white move. A black move at A would (at least in the short term) prevent the capture. Whether playing at A is a good idea for either player depends on the rest of the board, mainly on other stones nearby. This is one instance of a fairly general principle; if a move is good for either player, then it (or something nearby) is likely also good for the opponent.

If a group of stones has no liberties (connections to empty intersections), then it is captured and its stones are taken off the board. The "before" part of the diagram shows a black group in atari; a white move at A would take its only liberty and kill the group. The "after" part shows the result of that white move. A black move at A would (at least in the short term) prevent the capture. Whether playing at A is a good idea for either player depends on the rest of the board, mainly on other stones nearby. This is one instance of a fairly general principle; if a move is good for either player, then it (or something nearby) is likely also good for the opponent.

If a group still has liberties but is clearly bound to die, then the opponent need not complete the surrounding process; the stones remain in place until the end of the game and are then removed. If one player does not accept the idea that his or her stones are dead, then play continues until the issue is resolved.

A group with two eyes cannot be killed. In the picture, black would need to play on two points inside the white group to kill it. He or she cannot play on both in one turn and cannot play them on successive turns because the first move would be suicide.

A group with two eyes cannot be killed. In the picture, black would need to play on two points inside the white group to kill it. He or she cannot play on both in one turn and cannot play them on successive turns because the first move would be suicide.

In general this means that any group which both encloses several empty points and is fairly well-connected can live; with a few more stones it can usually form a fully connected group with two eyes. On the other hand, strong players sometimes manage to kill such groups before the eyes and connections are solidified. Perhaps more important, they quite often find plays that give them profit while the opponent is forced to play solidifying moves. Wasting too many moves to shore up weak groups is one of the many ways to lose a game, but then so are letting too much die or playing too conservatively so you have no weak groups but not enough territory.

A situation called ko arises fairly often; it looks as though one player could take one of the opponent's stones, the other could reply by taking the capturing stone, the first player could retake, and so on indefinitely. However, there is a rule to prevent such infinite repetitions; when one player takes a ko, the other is not allowed to take it back on the next move. If the ko is important, the other player will try to find a ko threat, a move the opponent cannot ignore without cost. If the opponent answers the threat, then take back the ko. If the opponent ignores the threat and resolves the ko, then make good on the threat to get compensation elsewhere for the loss of the ko.

A situation called ko arises fairly often; it looks as though one player could take one of the opponent's stones, the other could reply by taking the capturing stone, the first player could retake, and so on indefinitely. However, there is a rule to prevent such infinite repetitions; when one player takes a ko, the other is not allowed to take it back on the next move. If the ko is important, the other player will try to find a ko threat, a move the opponent cannot ignore without cost. If the opponent answers the threat, then take back the ko. If the opponent ignores the threat and resolves the ko, then make good on the threat to get compensation elsewhere for the loss of the ko.

Ko fights may go on for dozens of moves with the ko changing hands many times, and may involve threats by both players all over the board. Sometimes they can decide the outcome of a game, since the life of a group may depend on the outcome of a ko and ignoring a ko threat may be expensive.

Scoring

There are two main systems of scoring; area scoring is used in China and Taiwan, while territory scoring is used in Japan and South Korea, and is also the more common scoring system in Western countries. In both systems dead stones are removed before scoring, and each player scores one point for each empty space surrounded by his or her stones. In area scoring you then add the number of stones that player has on the board, while in territory scoring you subtract the number of stones captured by the opponent. In either system, white then gets some extra points called komi to compensate for black's advantage in playing first (usually 7.5 points in area scoring, 6.5 in territory scoring), and the player with the higher score after komi wins. The two scoring systems rarely result in a difference in outcome, and players are usually able to switch between them without difficulty.

Strategy and tactics

The strategy involved in go is quite complex, and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of a travel guide, but we cover some of the basics here.

Each player must try to strike several balances simultaneously:

- between taking territory immediately and building up influence for later use

- between attacking the opponent, defending his or her own formations, and expanding territory or influence

- between playing near existing stones and playing in some relatively empty region of the board where more territory may be available The idea of making good shape with your stones is important, especially in the opening and middle game. Often the best plays are multi-purpose; a single stone might strengthen a group, expand its territorial claim and make good shape, while another might both extend your moyo (territorial framework) and threaten an attack.

Among the things a player considers early in a game are fuseki (whole-board opening patterns), joseki (patterns in a single corner) and how those interact. Most joseki give some sort of more-or-less balanced trade; perhaps both players get decent shape and potential territory along different edges of the board, or one gets territory in the corner while the other gets influence toward the center. Usually, though, there are choices involved; which joseki sequence do you want, considering the rest of the board?

As in chess, in the middle game things become more complex and there may be intense fighting. Deep reading (looking many plays ahead) may be required to choose the next play. Parts of the end game are routine and can be dealt with by applying well-known formulae, but others require considerable reading and judgement.

Often questions of timing and the order of moves are important. The proverb Urgent moves before big moves helps some but is far from a complete answer. Usually there will be several reasonable-looking moves in different areas of the board, but which one should you play now? Which moves are sente (the opponent must or at least should answer, so you retain the initiative) and which are gote (the opponent can more-or-less safely ignore your move and take the initiative with a move elsewhere)? When should you tenuki, leave a joseki sequence or a fight in order to make an important move elsewhere?

Are there potentially good moves for the opponent that you can prevent by playing first in the area? Are there moves you should play before the opponent prevents them? If the opponent is building a large territory, can you just ignore that and build a larger one elsewhere? Should you invade the potential enemy territory? Or can you reduce its size, preferably while expanding your own territory?

Much of go revolves around the life and death of groups of stones. Most go problems (tsumego) ask the solver either to kill a group or to find a way to keep one alive. Similar questions routinely arise in actual play. Often you need to find the vital point of a group and play there; in other cases you need a clever move (tesuji).

In a capturing race (semeai) one or more groups of each colour is in danger and each player tries to kill at least one enemy group. The outcome depends mainly on how many liberties (connections to empty points) each group has, though various tactical details may complicate things. Capturing an enemy group will strengthen one of your groups, and often it makes your group entirely safe.

Often connecting groups or cutting the opponent's connections are important. In a semeai, a connected group may have enough liberties to win when neither of its parts would survive alone. In another simple example, two groups with one eye each will both die but connected they form an unkillable two-eyed group.

Rank and handicap

Go has a ranking system similar to those used in martial arts. Using the Japanese terms which have been adopted into English, beginners start at around 30 kyu and work their way up to 1 kyu. The next level is 1 dan or shodan (black belt in martial arts) and amateur ranks continue above that up to 6 or 7 dan. The Chinese equivalents are ji for kyu and duan for dan. Pros have a separate ranking system from 1 dan to 9 dan.

In online discussions, amateur ranks are written as, for example, 6k or 5d while pro ranks are shown as, for example, 3p. It is also common to abbreviate ranges, "sdk" for single-digit kyu and "ddk" for double-digit kyu.

Unlike most other board games, Go has an effective and routinely used handicap system which allows players of significantly different strength to have an interesting game. For players of approximately equal strength the board is initially empty, black plays first, and white gets komi; they may alternate colors in successive games.

When the strengths are unequal the stronger player always plays white, some black stones are placed on the board before play starts giving black an advantage, white plays first, and komi is half a point which makes drawn games impossible but does not otherwise affect the outcome. The number of stones is based on the difference in ranks; for example a 1k player would give a 7k six stones. This works rather well, at least for handicaps up to about six stones. In an even game (no handicap) the stronger player might be bored and the weaker one overwhelmed. With handicap, the stronger player may still win often but will usually have to work quite hard to do so, and the weaker player will probably win some games.

The range of strengths is enormous. A 9-kyu player can give a beginner nine stones and win easily; the game will be a lesson, not a contest. However the 9k takes nine stones from a 1-dan amateur (shodan) and that will be a contest; the 9k might win and will rightly be quite pleased if he or she does. Many clubs and nearly all online servers will have players that give the shodan two or more stones, and any professional player could give an amateur shodan at least six stones. Beyond that, a good AI program running on powerful hardware will usually defeat a human pro.

Destinations

In East Asian countries newspaper columns and TV shows about the game are common, almost every town has at least one club, as do many schools and most universities, and it is moderately common to see people playing in parks. Visitors are generally welcome to play, and in some places a foreign player may attract considerable attention as a "dancing bear". (It is not how well it dances; what is amazing is that it can dance at all.)

.jpg/440px-Dancing_bear_(2825583446).jpg)

- Sensei's Library has lists of local Go associations and of places to play on every continent.

- Baduk Club. This site has a map showing clubs; it is quite good for the Americas and Europe, but lists only a few places elsewhere. They also have a store specializing in club equipment and teaching gear, plus some vintage imports from Japan.

- Wu Qingyuan Game of Go Club (吴清源围棋会馆). One of the finest players of the 20th century was a Chinese who lived most of his life in Japan and is known in the West by his Japanese name, Go Seigen. This is a museum named with his Chinese name and located in his hometown. It also hosts a local club. See Fuzhou#Do for details.

- Shanghai parks. Players are often found in Jing'an Park (mostly in the southeast corner) and Fuxing Park (the French park), especially on weekends.

- Museum of Chinese Go (中国围棋博物馆). A comprehensive museum about go. The museum is run by the Hangzhou Branch of the China Chess Institute. Information is available in both Chinese and English.

- Luoyang Weiqi Museum. A private museum founded and curated by a devoted player. She also founded a company in the same town which produces Go equipment including ceramic stones.

- Kibi no Makibi Park (吉備真備公園). A park dedicated to Kibi no Makibi in Yakage where he was born. Kibi no Makibi went as an envoy to China and is attributed with introducing Go to Japan upon his return. The park was built over the spot of his former residence. 2021-09-18

- Makibi Park (まきび公園). A park in Kurashiki featuring an attractive Chinese garden and a small museum about Kibi no Makibi. 2021-09-18

Japan has two associations for the game Nihon Ki'in and Kansai Ki'in (Japanese-only web site). Both have shops for equipment and links to many places to play or study. The Korean Baduk Association, Chinese Weiqi Association and Taiwan Chi Yuan (Chinese-only web site) play similar roles.

Do

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan, China and Korea all had tours for Go players, most including some instruction from professional players. As far as we know as of late 2022, none of those have restarted yet.

- Baduk residency program. This program puts a group of 4 to 8 people in a large house where they can play a lot of Go. There is no professional instructor. There is also no charge — even room and board are free — but there is a requirement to do volunteer work promoting the game.

- Go camp Hungary. This is usually in summer, but as of November 2022 no 2023 announcement has been made

- Osaka Go Camp. 2023 dates are June 25 to July 13

- Zhang Jiayao 3p's Go Dojo. Teaching is done in Chinese.

Learn

Many pros and some strong amateurs give lessons. Weaker players often get some advice from stronger ones as just part of the game, nearly any Go club will have players willing to help beginners, and many players do some volunteer teaching, but if you want intensive coaching you will generally have to pay for it.

Various national or regional associations, such as those in the US and Europe or the Asian ones mentioned above, organize teaching events. and sometimes regional or local groups do as well. Some pros travel to teach at such events.

There are many online servers for playing the game, and teachers offer lessons on most of them. It can also be instructive just to observe other people's lessons and/or games between strong players, and this is free. There are also servers such as Black to Play for life-and-death problems or Josekipedia for openings.

- Go Teachers. A group of teachers, mostly based in Europe and including some pros, who offer online lessons. There are Go-playing programs for most computers and smartphones, and most can be used as teachers, either by just playing against them or by using them to analyze a game after it has been played. Some can also be used interactively, acting as a strong opponent who also suggests moves for you during the game; the best-known program of this type is Lizzie. To make these programs run quickly while playing well enough to instruct a dan player, you need a fairly powerful graphics processor; Nvidia is the most-used brand.

The Go Teaching Ladder was a site where people at any level could review games; for example a 1d player might do reviews for kyu players and get his or her games reviewed by high dan players. It is no longer doing reviews, but the archive of over 10,000 reviews is still online and is searchable in various ways; for example you can look at reviews where the players are around your level, or reviews done by pros. Kiseido Go Server has the KGS Teaching Ladder which is still active but has fewer archived reviews.

Sensei's Library has links to many commented pro games.

Both Japan and South Korea have schools for insei, candidates to become professional players; most travellers could not attend them since you need to already be a high dan amateur before they will admit you. However web search can turn up blogs by Westerners in those schools, and some make interesting reading.

Buy

Yunzi can be found in almost any Chinatown on Earth, usually for under $25. In China, look for them in the sports section of department stores, generally under ¥100.

The really cheap sets sold in China, with tiny plastic stones in rather ugly cylindrical plastic boxes, are not a good buy; they are intended for a different game (gomoku in Japanese or five-in-row in English) and have a 15x15 board rather than the 19x19 that is standard for Go.

In China, the bird and flower markets found in many towns are often the best place to look for better equipment. In the West, stores that specialize in games often have some Go equipment; Chinese or Korean import shops are less certain to stock it but often have interesting items if they do.

Sensei's Library has lists of places to buy equipment worldwide. They include many online sellers.

- Yunnan Weiqi Factory (website is nearly all in Chinese), +86 871 631 4013. This company are the manufacturers of yunzi stones, and they also make Japanese-style bi-convex stones. There are various grades at prices from a few hundred yuan to several thousand; the more expensive ones come with wooden bowls in carved wooden boxes. They also have boards. Their top-of-the-line products are fine enough that Mao presented a set to Queen Elizabeth.

- Kunming bird and flower market, 25.038°, 102.712°. Many of the Yunnan Weiqi Factory's products at a more convenient location.

- Dali, 25.700278°, 100.156389°. This scenic town on the Yunnan tourist trail is famous for marble, so much so that the Chinese name for marble is dali shi, Dali stone. A wide range of marble goods are available, including Go stones, bowls, boards and complete sets. Some players quite like these, but others find them rather clunky and inelegant. They certainly make an unusual souvenir, though they are inconveniently heavy.

- Wuyi Mountain, 27.75°, 118.02°. This is a scenic site in China's Fujian province, on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The nearby town has shops with many fine wooden handicrafts including Go bowls. The plain ones are under $20 a set and look more-or-less identical to bowls sold in Japan or the West for $100 or more. More expensive ones are carved from tree roots and have a lovely pattern of knots. Be careful, however, to get bowls that are large enough; some of these will not hold a full set of moderately thick stones.

- Jingdezhen, 29.3°, 117.2°. This city in Jiangxi province has been one of China's most famous producers of porcelain for over a thousand years. Products include ceramic go stones; these are fairly cheap but the only player commenting about them on Sensei's Library did not like them much.

- Ing stones. These are named after Taiwanese millionaire Ing Chang Ki who was a fanatic about the game and funded a foundation to promote it. The stones are large with a heavy metal center covered in a slightly soft plastic; some players prefer them and others detest them. They come in special bowls which make "Ing counting" (a type of area scoring) easier. They are common in Taiwan and can be found in Hong Kong, but rarely anywhere else, and are low cost.

- Kuroki Goishi, 8491 Hiraiwa, Hyuga City, Miyazaki Prefecture, +81-982-54-2531. A Japanese company that manufactures boards, bowls, and slate and clamshell stones. Located in Hyuga, the traditional source of clamshell stones. Not cheap, but reviews on Sensei's Library are very positive.

- Aoyama Go Shop, 1-4-9 Shinjuku Shinjuku-ku Tokyo Prefecture, 35.688378°, 139.710902°, +81 333542738. 10:00-19:00. A Go store in Shinjuku, Tokyo.

- Koma Tokyo. A company specializing in handmade wooden furniture, including some tables with Go boards built in. Lovely stuff, but not cheap.

- Daiso Japan. This is a large chain (over 3000 stores in Japan, over 1500 elsewhere), mostly for low-to-moderate priced household goods; it has been called "the Japanese dollar store". They have many stores across Southeast Asia, mostly in large malls, and some of those carry Go equipment.

- Second-hand in Japan Japanese generally do not like buying used goods, so prices in their "recycle shops" are often good. Sensei's Library discussion mentions flea markets in Kyoto as one good source.

High-end equipment can be expensive. A moderately fine set — wooden table board 5 cm (2 inches) thick plus reasonably nice bowls and stones — will typically be around $200. If you want stones in the traditional Japanese materials (clamshell for white, slate for black), or bowls in the traditional mulberry wood, those are each likely to be several hundred. A full-size board as illustrated will be at least $500, so the whole set might be well over $1000.

The equipment can also be heavy enough to be inconvenient to lug around during your travels, to cause difficulty with airline luggage weight allowances, or to incur large shipping costs if buying online. Fine-grained woods are preferred for board construction, and those are quite dense; a full-size board will be around 20 kg (44 pounds) and even a table board has significant heft. The stones are also made of dense materials and a set typically has 361 of them, so the weight adds up; if they are 5 g each, total weight is 1.8 kg (4 pounds).

The traditional wood for Japanese boards, kaya, is from a slow-growing tree (hence the coveted fine grain) that needs several hundred years to get big enough to make Go boards out of and is rare enough to be a protected species. Kaya is therefore in extremely short supply and kaya boards, bought new, are incredibly expensive; anything under $1000 should be considered a bargain and top-grade collector's item boards can fetch well over $10,000. Most travellers' only hope of getting a kaya board would be a lucky find in a Japanese flea market.

Some vendors offer boards in shin kaya, which translates literally as 'new kaya'; it is really just spruce with good marketing. A shin kaya board can be a good buy, but not at anything close to the price of real kaya.

Fortunately there are also many more moderately priced alternatives; for example the cost is much lower with any wood except kaya for the board, with any material except mulberry wood for the bowls, or with glass stones or yunzi instead of slate-and-shell. Cheaper sets may not be great examples of oriental traditions, but many are good enough to be quite pleasant to use.

A traveller visiting East Asia will often find better selection and prices than are available at home or online; one who is in the market for high-end equipment might even save enough to cover much of the cost of a trip.