Voyages of Roald Amundsen

Voyages of Roald Amundsen

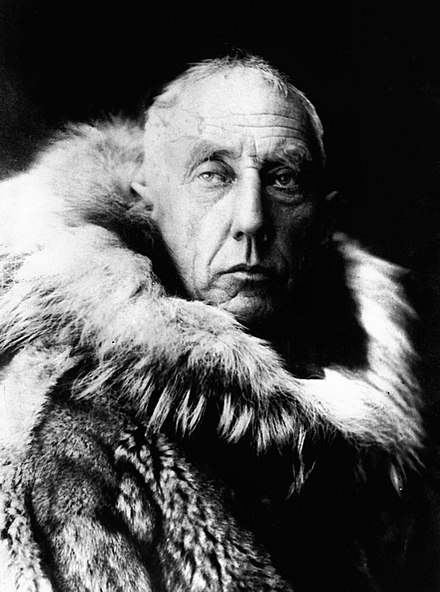

Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions and a key figure of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Understand

Amundsen and his contemporaries are often called the prime examples of the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration" which came to a definite end with the switch to a more scientific approach in the "international geophysical year" 1957/58, which established the Amundsen/Scott South Pole Station and launched the space race with Sputnik.

Amundsen and his contemporaries are often called the prime examples of the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration" which came to a definite end with the switch to a more scientific approach in the "international geophysical year" 1957/58, which established the Amundsen/Scott South Pole Station and launched the space race with Sputnik.

Youth

Amundsen was born on 16 July 1872 into a family of Norwegian shipowners and captains in Borge, between the towns Fredrikstad and Sarpsborg. His parents were Jens Amundsen and Hanna Sahlqvist. Roald was the fourth son in the family. His mother wanted him to avoid the family maritime trade, encouraging him to become a doctor, a promise that Amundsen kept until his mother died when he was aged 21. He promptly quit university for a life at sea.

At the age of 15, Amundsen was enthralled by reading Sir John Franklin's narratives of his overland Arctic expeditions. He decided that he wanted to be a polar explorer, and to become the first man to navigate the entire Northwest Passage. He later wrote "I read them with a fervid fascination which has shaped the whole course of my life".

Northwest Passage

He actually fulfilled his dream, on a long trip from 1903 to 1906. While planning the journey, he studied the life and deeds of Scottish Arctic explorer John Rae, the first European to visit and map the strait between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula (today named Rae Strait) in 1854, while searching for Franklin and the passage itself. He mapped the correct route, but failed to complete it; his exploring methods were somewhat emulated by Amundsen. Franklin's chosen passage down the west side of King William Island took his ships into "a ploughing train of ice ... [that] does not always clear during the short summers". Amundsen early decided on a route along the island's east coast, regularly clear in summer.

His ship Gjøa left the Oslofjord with a crew of seven on June 16, 1903, and made for the Labrador Sea west of Greenland. From there, she crossed Baffin Bay and navigated the narrow, icy straits of the Arctic Archipelago. By late September, Gjøa was on Rae Strait, and began to encounter worsening weather and sea ice. Amundsen put her into Gjoa Haven, a natural harbour on the south shore of King William Island; and by October 3, she was iced in. There she remained for nearly two years, with her crew undertaking sledge journeys to make measurements to determine the location of the North Magnetic Pole and learning from the local Inuit people. They left Gjoa Haven on August 13, 1905, and motored through the treacherous straits south of Victoria Island, and from there west into the Beaufort Sea. By October Gjøa was again iced-in, this time near Herschel Island in the Yukon. Amundsen left his men onboard and spent much of the winter skiing 500 miles south to Eagle, Alaska to telegraph news of the expedition's success. He returned in March 1906, but Gjøa remained icebound until July 11. She reached Nome on August 31, and sailed on to earthquake-ravaged San Francisco, where the expedition was met with a hero's welcome on October 19, 1906.

South Pole

_-_Fram.jpg/440px-Flickr_-_Riksarkivet_(National_Archives_of_Norway)_-_Fram.jpg) Amundsen next planned to take an expedition to the North Pole and explore the Arctic Basin. Finding it difficult to raise funds, when he heard in 1909 that the Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had claimed to reach the North Pole as a result of two different expeditions, he decided to reroute to Antarctica. He was not clear about his intentions, and Robert F. Scott and the Norwegian supporters later felt misled. Taking dogs and sleds aboard Nansen's ship Fram; they left Oslo for the south on 3 June 1910. At Madeira, Amundsen alerted his men that they would be heading to Antarctica, and sent a telegram to Scott: "Beg to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic—Amundsen." Fram arrived at the eastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf (then known as "the Great Ice Barrier"), at a large inlet called the Bay of Whales, on 14 January 1911. Using skis and dog sleds for transportation, Amundsen and his men created supply depots at 80°, 81° and 82° S, along a line directly south to the Pole. The team and 16 dogs departed base camp on 19 October and arrived at the Pole on 14 December, a month before Scott's group. Amundsen's trip was meticulously planned (even though he had to initially keep his intention of trying for the pole secret) and several members of his party actually gained weight on the way to the pole.

Amundsen next planned to take an expedition to the North Pole and explore the Arctic Basin. Finding it difficult to raise funds, when he heard in 1909 that the Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had claimed to reach the North Pole as a result of two different expeditions, he decided to reroute to Antarctica. He was not clear about his intentions, and Robert F. Scott and the Norwegian supporters later felt misled. Taking dogs and sleds aboard Nansen's ship Fram; they left Oslo for the south on 3 June 1910. At Madeira, Amundsen alerted his men that they would be heading to Antarctica, and sent a telegram to Scott: "Beg to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic—Amundsen." Fram arrived at the eastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf (then known as "the Great Ice Barrier"), at a large inlet called the Bay of Whales, on 14 January 1911. Using skis and dog sleds for transportation, Amundsen and his men created supply depots at 80°, 81° and 82° S, along a line directly south to the Pole. The team and 16 dogs departed base camp on 19 October and arrived at the Pole on 14 December, a month before Scott's group. Amundsen's trip was meticulously planned (even though he had to initially keep his intention of trying for the pole secret) and several members of his party actually gained weight on the way to the pole.

North Pole

Afterwards, in 1918, an expedition Amundsen began with a new ship, Maud, lasting until 1925. Maud was carefully navigated through the ice, west to east, through the Northeast Passage. The goal of the expedition was to explore the unknown areas of the Arctic Ocean, strongly inspired by Fridtjof Nansen's earlier expedition with Fram. The plan was to sail along the coast of Siberia and go into the ice farther to the north and east than Nansen had. In contrast to Amundsen's earlier expeditions, this was expected to yield more material for academic research, and he carried the geophysicist Harald Sverdrup on board. Amundsen encountered heavier ice than he expected, suffered a broken arm and was attacked by polar bears. After two winters frozen in the ice, without having achieved the goal of drifting over the North Pole, Amundsen decided to go to Nome to repair the ship and buy provisions. Several of the crew ashore there, including Hanssen, did not return on time to the ship. Amundsen considered Hanssen to be in breach of contract, and dismissed him from the crew.

During the third winter, Maud was frozen in the western Bering Strait. She finally became free and the expedition sailed south, reaching Seattle, in the American Pacific Northwest in 1921 for repairs. Amundsen returned to Norway, needing to put his finances in order. In June 1922, Amundsen returned to Maud, which had been sailed to Nome. He decided to shift from the planned naval expedition to aerial ones, and arranged to charter a plane. He divided the expedition team in two: one part, led by him, was to winter over and prepare for an attempt to fly over the pole in 1923.

The 1923 attempt to fly over the Pole failed. Amundsen and Oskar Omdal, of the Royal Norwegian Navy, tried to fly from Wainwright, Alaska, to Spitsbergen across the North Pole. When their aircraft was damaged, they abandoned the journey. To raise additional funds, Amundsen traveled around the United States in 1924 on a lecture tour. In 1925, accompanied by Lincoln Ellsworth, pilot Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, flight mechanic Karl Feucht and two other team members, Amundsen took two Dornier Do J flying boats, the N-24 and N-25, to 87° 44′ north. It was the northernmost latitude reached by plane up to that time. The aircraft landed a few miles apart without radio contact, yet the crews managed to reunite. The N-24 was damaged. Amundsen and his crew worked for more than three weeks to clean up an airstrip to take off from ice. They returned triumphant when everyone thought they had been lost forever.

In 1926, Amundsen and 15 other men, including Ellsworth, Riiser-Larsen, Oscar Wisting, and the Italian air crew led by his friend, the aeronautical engineer Umberto Nobile, made the first crossing of the Arctic in the airship Norge, designed by Nobile. They left Spitsbergen on 11 May 1926, flew over the North Pole on 12 May, and landed in Alaska the following day. Amundsen disappeared while taking part in a rescue mission for Nobile, stranded on his airship Italia, on 18 June 1928. Amundsen's French Latham 47 flying boat never returned, but a crash was confirmed by later discovery of parts of a wreck, that were undoubtedly this plane.

In 1926, Amundsen and 15 other men, including Ellsworth, Riiser-Larsen, Oscar Wisting, and the Italian air crew led by his friend, the aeronautical engineer Umberto Nobile, made the first crossing of the Arctic in the airship Norge, designed by Nobile. They left Spitsbergen on 11 May 1926, flew over the North Pole on 12 May, and landed in Alaska the following day. Amundsen disappeared while taking part in a rescue mission for Nobile, stranded on his airship Italia, on 18 June 1928. Amundsen's French Latham 47 flying boat never returned, but a crash was confirmed by later discovery of parts of a wreck, that were undoubtedly this plane.

See

Norway

- The Fram Museum (Frammuseet), West, Oslo. A museum telling the story of Norwegian polar exploration and three Norwegian polar explorers in particular—Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup and Roald Amundsen. The Gjøa, the first vessel to transit the Northwest Passage, led by Amundsen, is in a dedicated building at the museum. 2020-05-13

- Roald Amundsen's House Uranienborg (Roald Amundsens hjem), Roald Amundsens vei 192, Svartskog (outside Oslo), 59.7861817°, 10.7317923°, +47 66 93 66 36. This was Roald Amundsen’s home for 20 years, until he disappeared in 1928, much as he left it when he departed. Objects, souvenirs and gifts that he brought back from expeditions and various lecture tours. 2020-05-13

- The Polar Museum, Søndre Tollbodgaten 11, Tromsø (in a wharf house from 1837), 69.65227°, 18.96337°. Presents Tromsø's past as a centre for Arctic hunting and starting point for Arctic expeditions. There's a permanent exhibition on the expeditions of Roald Amundsen. 2020-05-15

- Roald Amundsen Monument, Tromsø, Norway, 69.6480449°, 18.9567224°. Central plaza with benches and the bronze statue of the famed Norwegian polar explorer. 2020-05-15

- Vollen, Oslo's urban area. In 1916 (or 1917) the Arctic expedition ship Maud, designed and built especially for Roald Amundsen, was built here and launched into Oslofjord. She sailed through the Northeast Passage between 1918 and 1924. Sold to the Hudson's Bay Company as the supply vessel Baymaud, she sank at Cambridge Bay, Northwest Territories (now Nunavut), Canada in 1930. In 2011, a new project was commenced to salvage Maud and transport her to a new museum to be built at Vollen. On 31 July 2016, the hull of Maud was raised to the surface and placed on a barge; In August 2017 Maud began the journey back to Norway, and arrived in Bergen on 6 August 2018, nearly a century after her departure with Amundsen. She was then towed along the Norwegian coast, and arrived at Vollen on 18 August. As of May 2020, its museum is not yet built. 2020-05-25

- Svalbard (sometimes referred to as Spitsbergen, the main island with all the settlements), The islands are directly north of Norway, and under Norwegian rule since 1920. Amundsen docked here many times. 2020-05-25

North America

- Nattilik Heritage Centre, Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, Canada, +1 867-360-6035. Opened on 17 October 2013. It displays a collection of Netsilik handmade harpoons, snow goggles and snow knives purchased by Amundsen, and returned here after years on display at the museum of cultural history in Oslo. 2020-05-13

- Northwest Passage Territorial Park, Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, Canada. The park consists of six areas, showing part the history of the exploration of the Northwest Passage, and of the first successful passage by Roald Amundsen aboard Gjøa. 2020-05-15

- Nome, Alaska, USA. Amundsen also docked here many times. 2020-05-25

Antarctica

- Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station. The ultimate destination for Amundsen fans.