D-Day beaches - landing operations of the Allied invasion of Normandy

The D-Day Beaches are in the Calvados and Manche departments of Normandy, France. They were the landing places for the Allied invasion of western Europe during World War II.

An excellent time to visit is on the June 6th anniversary when there are numerous memorial ceremonies to mark the occasion. A large number of reenactment groups attend, adding pageantry and atmosphere. The church bells ring in the towns to celebrate the anniversary of their liberation. The French people will be happy to see you - these people remember, and the welcome will be warm.

It has been a long time since 1944 and not many of the old soldiers survive, but those that do often return to these beaches on June 6th. For the 70th anniversary in 2014, 90-year-old Royal Navy veteran Bernard Jordan was denied permission to leave his nursing home because of his health; he snuck out and got on a ferry to France anyway. Two elderly paratroopers, a 93-year-old American and an 89-year-old Briton, jumped into France that day as they had 70 years earlier.

Understand

See World War II in Europe for context.

On 6 June 1944 (D-Day), the long-awaited invasion of Northwest Europe (Operation Overlord) began with Allied landings on the coast of Normandy (Operation Neptune).

The task was formidable, for the Germans had turned the coastline into an interlinked series of strongpoints with artillery, machine guns, pillboxes, barbed wire, land mines, and beach obstacles. Germany had 50 divisions in northern France and the Low Countries, including at least a dozen in position to immediately be used against this invasion.

Following an extensive air and sea bombardment of the assault areas, the Allies launched a simultaneous landing of U.S., British and Canadian forces. About 160,000 ground troops landed that day, roughly half American and half Commonwealth. About 4,000 ships, 11,000 planes, and many thousands of sailors and airmen also took part in the operation.

Overall commander of Allied forces in Europe was the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would later become the country's president, while the British General Bernard Montgomery was in charge of the ground forces in Normandy once they landed. On the German side, General Erwin Rommel was in charge of coastal defenses while Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt had overall command in the region.

This was the largest seaborne invasion in history and an important Allied victory, though the costs in both lives and material were enormous.

The landings

<blockquote>_The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you._ – <small>General Dwight D. Eisenhower</small></blockquote>Just after midnight 24,000 men came in by parachute and glider on the flanks, to secure key points. Then the main seaborne landings on five separate beaches began at dawn. East-to-west, the attacks were:

-

The British 6th Airborne, with one Canadian battalion, on the left flank near Caen

- Mémorial Pégasus, av du Major Howard, 14860 Ranville, +33 2 31 78 19 44. The capture of Pegasus Bridge was a remarkable achievement of the Glider Pilot regiment and the Sixth British Airborne. The story is well covered in the museum where exhibits include the original Pégasus Bridge and a Horsa Glider. Several monuments to the Sixth British Airborne are beside the bridge. €7.50

-

Sword Beach (British), 49.2988°, -0.3055°.

-

Juno Beach (Canadian), 49.332°, -0.399°.

-

Gold Beach (British), 49.346°, -0.554°.

-

Omaha Beach (American), 49.3720°, -0.8836°.

-

Utah Beach (American), 49.415402777°, -1.174647222°.

-

The US 82nd and 101st Airborne, on the right flank around Sainte-Mère-Église

Every beach has monuments and museums; see the Beaches section below for details.

When the seaborne units began to land, the allied soldiers stormed the beaches against strong opposition, despite mines and obstacles. They raced across open beaches swept with machine gun fire and stormed the German gun positions. In fierce hand-to-hand fighting, they fought their way into the towns and hills and then advanced inland. Casualties were heavy in all areas and on both sides, though initially the Germans in their fortified positions had lighter losses than the Allies.

When the seaborne units began to land, the allied soldiers stormed the beaches against strong opposition, despite mines and obstacles. They raced across open beaches swept with machine gun fire and stormed the German gun positions. In fierce hand-to-hand fighting, they fought their way into the towns and hills and then advanced inland. Casualties were heavy in all areas and on both sides, though initially the Germans in their fortified positions had lighter losses than the Allies.

“As we near the edge of the water we spread out. Other craft have grounded further along the beach. We are now abreast of them. They are disembarking with all types of material about their person, just as helpless as myself to shoot back the beach defenders. Some of the boys go down at the water's edge for a breather, but they come under direct machine-gun fire which criss-crosses the whole beach. Thank Heaven! " – <small>John Robson, Hull Daily Mail</small>

By the end of the day the 3rd British Division was within three miles of Caen, the 3rd Canadian Division was well established on its intermediate objectives and the 50th British Division was only two miles from Bayeux. In the American zone, the 4th Division had established a 4-mile deep penetration inland and was within reach of Ste-Mere-Eglise, where the 82nd had fought throughout the night. At Omaha Beach the Germans had an advantage of terrain from the bluffs above the landing sites, but there too beachheads had been established.

It was a magnificent accomplishment; the formidable Atlantic Wall had been successfully breached. By the end of D-Day, the Allies had landed more than 150,000 troops in France by sea and air, 6,000 vehicles including 900 tanks, 600 guns, and about 4,000 tons of supplies and, astonishingly, they had achieved complete surprise in doing it. More soldiers and supplies were pouring ashore to continue the advance; by early July the Allies had over a million men in France, and in August the total reached two million.

Other allies

The main invading force was American, British and Canadian, but several other allies had observers present or were involved in other ways.

The captive nations of Europe contributed significantly to their own liberation; they all (even Germany) had resistance movements, and several also had more formal forces involved; on D-Day there were Free French on the beaches, and Norwegian, Dutch and Polish Navy ships offshore. A Polish armoured division fought as part of the Canadian army in Normandy. From D-Day through all the fighting in France, Belgium and Holland, the resistance disrupted both German communications and their efforts to move urgently-needed reinforcements and supplies. On D-Day, Free French paratroopers were dropped in Brittany (the region west of Normandy) to help with that; their success was a factor in the American victories on the Cotentin Peninsula shortly after D-Day and in Brittany later.

By the time of this war the British Empire was far past its peak, but it was still a force to be reckoned with. On D-Day about half the landing force were British or Canadian, and the Empire made contributions beyond that. Ships of the New Zealand merchant marine delivered troops and British-based squadrons of Commonwealth air forces were in action along with the RAF and USAF. Also, every branch of the British services included personnel from other countries of the Empire.

Towns

The usual bases for visits to the beaches are either Caen or Bayeux; all the beaches are easily reached from either, though both are a bit inland not right on the beaches.

Caen is the main city of the department of Calvados, and the second most important city in Normandy after Rouen; it has various attractions and excellent shopping. It is about 15 km (10 miles) from the coast.

- Mémorial de Caen. This museum offers daily tours of the beaches and shows some good films of both the landings and the rest of the campaign in Normandy. Bayeux is a smaller town, closer to the coast and to the center of the invasion landing area. It is easy to get in and out of, and convenient for visiting the Omaha, Gold and Juno beach sectors. It has excellent restaurants and shops with an interesting pedestrian section.

- Musée Mémorial de la Bataille de Normandie (Battle of Normandy Memorial Museum), boul Fabian Ware, 14400 Bayeux, +33 2 31 51 46 90. This museum offers a chronological presentation of the events of the Battle of Normandy along with an exhibition of equipment, small arms, weapons and uniforms, films, mementos and slides. English and French. Outside: German "Marder" anti-tank vehicle, Sherman Tank, American tank destroyer, and a British "crocodile" flame-throwing tank. Inside: American self-propelled 105 mm howitzer, Radio truck, armored bulldozer, American quad-50 caliber anti-aircraft gun (aka "meat chopper"), and several other large weapons. One of the best D-Day museums to offer a balance of artifacts on the one hand together with explanations and historical context on the other.

- Musée Mémorial du General de Gaulle (General de Gaulle Memorial), 10, rue Bourbesneur, 14400 Bayeux, +33 2 31 92 45 55. In the former Governor's House, this museum is dedicated to the numerous visits made by the general to Bayeux and in particular, the two important speeches delivered on 14 June 1944 and 16 June 1946. Film archives, photos, manuscripts, documents and memorabilia.

There are other choices.

- Ouistreham is on the coast at the eastern end of the landing area, on Sword Beach, and may be convenient because it has a ferry from Portsmouth.

- Arromanches-les-Bains is on the coast near the center, on Gold Beach, and was one site where a "mulberry harbour" (artificial port) was built shortly after D-Day.

- Sainte-Mère-Église is to the west, inland of Utah Beach; American paratroopers were dropped in the area a few hours before the seaborne invasion and fought a fierce battle in and around the town. The area has many other villages; most are quite picturesque and are able to accommodate tourists.

One could also stay in one of the towns outside the actual landing area where an important battle was fought in the weeks after D Day. See the Normandy campaign section below for details.

Almost every town in this area was damaged during the war; some — such as Caen, Saint-Lô, Vire and Falaise — were mostly destroyed. However, they have all long since been rebuilt. Bayeux was fortunately undamaged and so still retains the Medieval character.

Climate

Normandy has a temperate-zone maritime climate. The summers are warm and winters are mild. Rain however is a part of the climate all year round, winter seeing more rain than summer. The ongoing rain isn't enough to spoil a vacation most of the time and it does have a benefit, the nature is incredibly lush and green. Winter does see the occasional snow and frost as well, but in general the climate is pretty moderate in winter.

Summers are a little warmer than in southern Britain with up to 8 hours of sunshine per day. Cyclists love the region because it is not nearly as hot as most other parts of France and can be more compared to southern England than inland France. Either way, sunscreen and a hat are necessary; even if it doesn't feel as hot as the rest of France, the sun is still beating down with force!

Get in

Normandy is easily reachable from Paris, either by car (2 to 3 hours drive) or by train (2 hours from Paris St Lazare station to Caen central station).

Alternatively, a ferry across the channel will take you in just over three hours from Portsmouth to Ouistreham, the easternmost D-Day target, an ideal starting point. Portsmouth was one of the ports from which the invasion was launched and has a D-Day Museum.

Other ferries go to Cherbourg and Le Havre, nearby though not in the actual landing area. Cherbourg is a major city and was liberated by the Americans in late June; see Contentin Peninsula below. Le Havre is a smaller town and further from the beaches; it was a German naval base, mainly for torpedo boats. It was liberated by a British and Canadian force in early September after some of the heaviest bombing of the war and a fierce fight on the ground.

Caen also has an airport, near the village of Carpiquet west of the city. Control of the airfield was fiercely contested in the weeks after D-Day.

Get around

Tour the beaches and battlefields, see the various museums and cemeteries throughout the area, and visit the seaside villages and towns. Independent travel either by car or using public transport is possible.

Local tourist information offices provide a leaflet (in English) that lists key visitor attractions, and has details of seven route itineraries which are also signposted on the road network.

By car

Car rental in Normandy can be arranged through several international chains including Avis, Budget, Eurocar, and Hertz. Cars can be picked up in Caen. Driving in France is on the right-hand side of the road and all distance and speed measurements are in km.

Bus

Bus routes in Normandy with services between Caen and Bayeux, Bayeux and Ouistreham, and Bayeux to Grandcamp. These cover most of the main landing beaches. All the routes are operated by Bus Verts du Calvados 09 70 83 00 14 (non-geographic number) , and free timetables can be acquired from the main tourist offices.

From Bayeux train station, you can catch a bus to some of the D-Day beaches. On the bus website there is a map of the bus route to the D-Day beaches. Bus 70 takes you to Omaha beach, the American cemetery, and to Pointe Du Hoc. Bus 74 takes you to Arromanches Beach, the location of the Mulberry harbors. According to Wikipedia: "Omaha beach is 5 miles (8 km) long, from east of Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes to west of Vierville-sur-Mer" and these villages are accessible via Bus 70. Buses are few and far between, so take the few number of buses into account. Also, buses do not run when there is heavy snow, so check the bus website beforehand during snow season.

Bicycle

Bike tours are very popular in France and biking is an excellent way of visiting the battlefields. You can rent bicycles at most major towns and railway stations in France.

On D-Day, some of the invading troops used bicycles; see the photos below of British troops at Lion-sur-Mer and Canadians at Juno Beach.

Guided tours

Guided tours including transport are available; most travel agents in the area and many of the hotels can arrange these if required. In Caen or Bayeux, some companies offer half-day or full-day guided tours to the battlefields with English-speaking guides.

- Normandy Sightseeing Tours offers tours from Bayeux to all five landing beaches and beyond. They use 8-seat vans, for smaller groups and a better experience. The guides are French and mostly locals from Normandy, all English-speaking.

- La Rouge Tours is one example of tours led by professional Battlefield Guides, mostly conducted by former servicemen. The Memorial de Caen museum also conducts daily tours of the beaches.

Beaches

Now more than 70 years after D-Day, the Normandy coastline is peaceful with lovely seaside towns and picturesque beaches. Many of the towns have names of the form something-sur-mer; sur-mer is French for "on the sea". Behind the coast is an old-fashioned farming landscape of grain fields, cattle and pastures, hedges and farmhouses.

"Take time to stroll on the beaches and through the villages and to drive country lanes that are once again regulated by rural rhythms, just as if they’d never been devastated at all. It's pretty and poignant, and here’s a strange thing, it brings out the best in people. There’s respect in the air and a common bond between visitors. Folk behave well, smile and chat more easily than usual."<br/>Anthony Peregrine, The Sunday Times.

However, the memories of war and D-Day are engrained in the landscape. Along the 80-km (50-mile) D-Day invasion coast there are the remains of German gun emplacements and bunkers, while war memorials and monuments mark where the allied forces landed. Inland, there are monuments in almost every village and at every bend in the road, for there is barely a square yard that wasn’t fought over. Along the coast and inland there are numerous D-Day related museums. Only by visiting do you get a proper idea of the vastness of the enterprise.

The following description of the beaches is organized in an east-to-west order, so that it can be used to plan a driving or biking tour along the coast. The length of a tour depends on how many sites and museums a person decides to visit. Enthusiasts could spend several weeks, but two or three days are enough to cover the major sites. A good starting point is to get an orientation to the area and the history of D-Day at either the Mémorial de Caen or Musée du Débarquement (The Landing Museum) in Arromanches, and from there set out to explore.

The beaches are still known today by their D-Day code names.

Sword Beach

Sword beach, the most easterly of the five beaches, stretches from Ouistreham to Luc-sur-Mer. The British 3rd Infantry Division landed on the 4 km (2½-miles) of beach between Ouistreham and Lion-sur-mer. The 41st Royal Marine Commando landed at Lion-sur-Mer, while the N°4 British Commando landed at Ouistreham. Integrated with the N°4 British Commando were 177 Frenchmen of the 1st Battalion of Fusiliers Marins Commandos who were granted the honor to set foot on Normandy soil in the first wave. On the eastern flank of Sword beach, the Sixth British Airborne had parachuted in the early morning hours of June 6th to seize bridges over the River Orne and Caen canal, silence gun batteries and secure the eastern flank of the D-Day beaches. A coup de main attack captured Pegasus and Horsa bridges to ensure access to the high ground overlooking Sword was secured.

Sword beach, the most easterly of the five beaches, stretches from Ouistreham to Luc-sur-Mer. The British 3rd Infantry Division landed on the 4 km (2½-miles) of beach between Ouistreham and Lion-sur-mer. The 41st Royal Marine Commando landed at Lion-sur-Mer, while the N°4 British Commando landed at Ouistreham. Integrated with the N°4 British Commando were 177 Frenchmen of the 1st Battalion of Fusiliers Marins Commandos who were granted the honor to set foot on Normandy soil in the first wave. On the eastern flank of Sword beach, the Sixth British Airborne had parachuted in the early morning hours of June 6th to seize bridges over the River Orne and Caen canal, silence gun batteries and secure the eastern flank of the D-Day beaches. A coup de main attack captured Pegasus and Horsa bridges to ensure access to the high ground overlooking Sword was secured.

The Germans fought hard on all beaches, but Sword was the only one where they were able to mount a counter-attack with an armoured division on D-Day itself. This caused heavy casualties and stopped the British advance for a time.

-

Musée de la Batterie de Merville, Place du 9ème Bataillon, 14810 Merville-Franceville (In the Merville coastal battery casemate), +33 2 31 91 47 53. The museum retraces the operations of the British Sixth Airborne. 6.50€

-

Site D’Ouistreham. This beautiful seaside resort town has a legacy of fortifications, memorials, museums and military cemeteries, that stand at ease between beach hotels, fine stretches of sand, breezy cliffs and postcard-picturesque fishing harbours. There are several monuments in the town including the Free French monument, Royal Navy and Royal Marines monument, 13th/18th Royal Hussars monument, and N°4 Commando plaques. The Kieffer monument stands atop a German bunker and is named for the Commando Lieutenant who led the attack that took it.

-

Musée Nr 4 Commando (N° 4 Commando Museum), Place Alfred Thomas, 14150 Ouistreham, +33 2 31 96 63 10. In this museum one can see scale models, weapons, and uniforms to retrace the story of the Franco-British Commandos who landed on Sword Beach.

-

Musée du Mur de L’Atlantique (Atlantic Wall Museum), av du 6 Juin, 14150 Ouistreham, +33 2 31 97 28 69. In a former artillery range-finding post on the Atlantic Wall, this 17 m high concrete tower is the only one of its kind and has been restored and re-equipped to its original state. 7€

-

Site de Lion-sur-Mer. Monuments include the Liberation monument, Royal Engineers Corps monument, and 41st Royal Marine Commando stele.

-

Site de Colleville-Montgomery. A plaque is located on the Hillman Battery main blockhouse in memory of the 1st Battalion the Suffolk Regiment soldiers. There is also a General Montgomery statue and the Provisional Cemetery, Kieffer and Montgomery monument.

-

Site D’Hermanville. Monuments in the area include 3rd Infantry Division and South Lancashire monument, Royal Artillery monument, Allied headquarters and Field hospital plaques, and Allied Navy sailors monument. The British Cemetery Hermanville-sur-Mer, where 1,003 soldiers rest is close to Hermanville-sur-Mer.

-

Musée Du Radar (Radar Museum), Route de Basly 14440 Douvres la Délivrande, +33 2 31 06 06 45. On the site of a German fortified radar base, the museum explains the evolution and operation of radar. Outside one can observe a German radar Würzburg.

There are two Commonwealth cemeteries near this beach; see the cemeteries section for details.

Juno Beach

Juno beach is five miles wide and includes the towns of St. Aubin-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and 2nd Armoured Brigade landed here and fought their way across the beaches and into the towns. The No. 48 Royal Marine Commando secured the left flank at Langrune-sur-Mer.

Juno beach is five miles wide and includes the towns of St. Aubin-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division and 2nd Armoured Brigade landed here and fought their way across the beaches and into the towns. The No. 48 Royal Marine Commando secured the left flank at Langrune-sur-Mer.

The coastline bristled with guns, concrete emplacements, pillboxes, fields of barbed wire and mines. The opposition the Canadians faced as they landed was stronger than at any other beach except Omaha.

-

Site de Langrune-sur-Mer. In the town center, on the sea front is the 48th Royal Marine Commando monument. In the entrance hall of the city hall there is a plaque in memory of the friendship between the 48th Royal Marines Commando veterans and the citizens of Langrune-sur-Mer.

-

Site de Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer. A 50-mm gun casement has been preserved at Place du Canada. There are stone memorials to the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment, Fort Garry Horse, and 48th Royal Marine Commando here.

-

Site de Bernières-sur-Mer. This pretty seaside village is distinguished by its church with a 13th century bell tower and 67 m (220 ft) spire. La Maison Queen's Own Rifles of Canada commemorates the men of this regiment. The house is one the famous houses on the beach as it appeared in many newsreels and official photos. Memorials to the Queen's Own Rifles, Le Regiment de la Chaudière, and Fort Garry Horse are by a German bunker at La Place du Canada. There is an excellent view of the beach from the bunker position and you can imagine what it must have been like when 800 men of the Queens's Own Rifles stormed ashore here as the lead wave of the dramatic D-Day assault. There are also the North Nova Scotia Highlanders plaque and Journalists HQ plaque. There is a walkway on the seawall that makes for a pleasant stroll along the ocean. If you walk east along the seawall about ½ km, you can see the house that appears in the background on the famous film footage showing the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada storming the beach on D-Day.

-

Site de Courseulles-sur-Mer. In the Courseulles-sur-Mer town centre, on the sea front there is a Sherman Duplex Drive (DD) tank on display. These tanks were partly amphibious, capable of swimming ashore from their landing craft; the soldiers interpreted "DD" as "Donald Duck". This tank was recovered in 1970 from the sea and restored. Badges of regimental units who fought in the area are welded to it.<br/>Monuments in the area include the Royal Winnipeg Rifles monument, Regina Rifles Regiment stele, Canadian Scottish Regiment stele, Royal Engineers plaque, and the Liberation and De Gaulle monument.<br/>The Croix de Lorraine monument commemorates the return of General de Gaulle to France.

-

Centre Juno Beach (Juno Beach Centre), voie des Français Libres, 14470 Courseulles-sur-Mer, 49.336389°, -0.461667°, +33 2 31 37 32 17. The Juno Beach Centre presents Canada's role in military operations and the war effort on the home front in World War II. Film, audio and displays bring pre-war and wartime Canada alive, as well as covering the fighting experiences. Juno Park at the front of the centre has walkways with interpretation panels, a preserved German bunker, and a path leading to the beach. There is little development here, so nothing interrupts your contemplation of beach and ocean. You can imagine the sands littered with mines-on-sticks, spiky metal “hedgehogs”, barbed wire and other barbarisms intended to rip the heart out of landing craft and the 14,000 Canadians that landed in this area. 7€

-

Site de Graye-sur-Mer. Monuments include the Liberation monument , Churchill "One Charlie" tank, breakthrough plaque, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, and 1st Canadian Scottish plaque, Canadian plaque, and Inns of Court monument.

There is a Canadian cemetery near this beach; see the cemeteries section.

Star Trek enthusiasts may be interested to know that James Doonan — the actor who played Scotty in the original series — was a Canadian officer who was wounded on this beach.

Gold Beach

Gold beach is more than 5 miles wide and includes the towns of La Rivière, Le Hamel and Arromanches-les-Bains. The British 50th Infantry Division and 8th Armoured Brigade landed here. The 47th Royal Marine Commando landed on the western flank with the objective to take Port-en-Bessin.

- Musée America Gold Beach (America Gold Beach Museum), 2, Place Amiral Byrd, 14114 Ver-sur-Mer, +33 2 31 22 58 58. This museum recounts the 1st airmail flight between the USA and France, together with a retrospective of the D-Day Landing and the British beachhead on Gold Beach.

-

Arromanches 360, Chemin du Calvaire, 14117 Arromanches, +33 2 31 22 30 30. The film The Price Of Freedom impressively mixes archived film from June 1944 with present day pictures and is presented on 9 screens in a circular theater.

-

Mulberry harbour. At Arromanches, you’re looking down a stretch of Gold Beach and site of the Mulberry harbour. The invasion needed a port to bring in supplies on a huge scale. So the allies built concrete pontoons that were towed across the channel and sunk to form the port’s outer perimeter. Twenty of the original 115 pontoons still defy the waves.

-

Musée du Débarquement (The Landing Museum), Place du 6 Juin, 14117 Arromanches, +33 2 31 22 34 31. In front of the actual vestiges of the Mulberries, this museum is devoted to the incredible feat of technology achieved by the British in building and setting up the artificial harbour. Period newsreel movies in English and French. Impressive dynamic scale-models showing how the floating docks rolled with the waves and tides. A 75-foot section of Mulberry floating bridge on display outside. Military equipment is on display outside, including an American half-track and a Higgins boat. £3.90

-

Batterie de Longues, Longues-sur-Mer (Access from the D514 road (follow the road-signs)), +33 2 31 06 06 45. The Longues-sur-Mer battery housed four 150mm guns with a range of 20 km and gave the Allied ships a pounding on the morning of 6 June. It is the only coastal battery to have kept its guns, giving an impressive picture of what an Atlantic Wall gun emplacement was really like.

-

Site de Port-en-Bessin. A monument in memory of the 47th Royal Marine Commando soldiers who were killed during the liberation of Port-en-Bessin and Asnelles is on top of the cliff, on the west side of the harbor.

-

Musée des épaves sous-marines (Underwater Wrecks Museum), Route de Bayeux-Commes, 14520 Port-en-Bessin, +33 2 31 21 17 06. This museum presents recovered wrecks and artifacts from more than twenty-five years of under-water exploration, in the coastal landing area. Debris includes a Sherman tank.

The Bayeux War Cemetery is not far inland of this beach, and the Bayeaux Memorial near it commemorates soldiers with no known grave. See the cemeteries section for details.

Omaha Beach

Omaha beach is overlooked by bluffs which rise to 150 feet (46 m) and command the beaches. These naturally strong defensive positions had been skillfully fortified with concrete gun emplacements, anti-tank guns and machine guns. In particular the guns at Pointe du Hoc were in position to be deadly, although they weren't actually firing on D-Day and it was Maisy battery that continued to fire onto both American beaches for three days. Allied bombing left these largely undamaged, and since there was no cover on the beach, this tranquil strand of beach became a killing field. Within a mile to the rear of the beach lay the fortified villages of Colleville-sur-Mer, Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer and Vierville-sur-Mer.

Omaha beach is overlooked by bluffs which rise to 150 feet (46 m) and command the beaches. These naturally strong defensive positions had been skillfully fortified with concrete gun emplacements, anti-tank guns and machine guns. In particular the guns at Pointe du Hoc were in position to be deadly, although they weren't actually firing on D-Day and it was Maisy battery that continued to fire onto both American beaches for three days. Allied bombing left these largely undamaged, and since there was no cover on the beach, this tranquil strand of beach became a killing field. Within a mile to the rear of the beach lay the fortified villages of Colleville-sur-Mer, Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer and Vierville-sur-Mer.

The US 1st Infantry Division had the most difficult landing of the whole Allied assault on D-Day and took around 2,000 casualties. One reason was the terrain, another that they faced the only German division on the coast which had a full complement of German troops. There were four divisions on the Cotentin Peninsula and several defending the British and Canadian beaches to the east, but those divisions were either below strength or composed partly of Russian, Polish and other forced conscripts.

The Omaha Beach landing is shown in the Oscar-winning film Saving Private Ryan and, unlike much from Hollywood, the battle scenes are quite realistic. However, the landing sequences were filmed on beaches in County Wexford, Ireland which bear little physical resemblance to the beaches in Normandy.

-

1st Infantry Division Monument. A monument dedicated to the “Big Red One”, the US 1st Infantry Division, is on the sea front, within walking distance from the American cemetery. Other monuments in the area include the 5th Engineer Special Brigade Memorial, and plaques commemorating the American armoured vehicles that passed through here.

-

2nd Infantry Division Monument, 49.36448°, -0.86366°. A monument dedicated to the US 2nd Infantry Division is on the sea front, by the German defensive bunker, Widerstandsnest 65 (WN 65), that defended the route up the Ruquet Valley to Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer.

-

Musée Mémorial d’Omaha Beach (Omaha Beach Memorial Museum), av de la Libération, 14710 Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, +33 2 31 21 97 44. This museum has a fine collection of uniforms, weapons, personal objects and vehicles. Dioramas, photos, and maps together with a film featuring veterans’ testimonies explain the landings at Omaha Beach and at Pointe du Hoc. A landing ship, Sherman tank and "Long Tom" 155 mm gun are on display outside.

-

Musée D-Day Omaha (Omaha D-Day Museum), Route de Grandcamp-Maisy, 14710 Vierville-sur-Mer, +33 2 31 21 71 80. Devoted to the landing on Omaha Beach. Various equipment is displayed including: vehicles, weapons, radios, and engineer equipment.

-

Site de Vierville-sur-Mer. Monuments here include the 29th US Infantry Division stele, National Guard monument, 6th Engineer Special Brigade stele, 29th DI Engineer plate, 81st CM battalion, and 110th FA bat. Plates, 5th Rangers Battalion plate, 58th Armored Field Battalion stele, boundary marker in memory of the 58th Artillery Battalion. Along the coastal road, 500 m from Les Moulins, is a monument on the site of the first American cemetery in Normandy on Omaha Beach. The soldiers interred there were later moved to the military cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. The beach's desolation makes it a powerful site to imagine soldiers battling on the sand, completely vulnerable to German artillery.

-

La Pointe du Hoc. A rocky headland towering over the beaches, La Pointe du Hoc has become a symbol of the courage of American troops. Here, Germans had placed bunkers and artillery. The positions were bombed, shelled and then attacked by 225 US Rangers, who scaled the 35 m rock wall, besieged the bunkers, and finally took them, only to find there were no guns at all. The guns had been dismantled and hidden in an orchard inland. Only 90 rangers were still standing at the summit. Today, bomb and shell craters remain. There is a monument in memory of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, who assaulted and captured La Pointe du Hoc battery. The memorial is built on a control firing casemate where bodies of the soldiers still lie under the ruins.

-

Musée des Batteries de Maisy (Ranger Objective). This outdoor German group of artillery batteries and HQ has been preserved and is camouflaged in over 14 hectares of land close to Grandcamp Maisy. The site covered the Omaha Sector and opened fire at Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc on the morning of D-day. The US 29th Division as well as the 5th and 2nd Rangers attacked the site on 9 June 1944 and after heavy fighting they captured the position. It is the largest German position in the invasion area and has original field guns, Landing craft and other D-day objects on display. American Rangers monument is on the site. 2018-06-01

There is an American cemetery near this beach; see the cemeteries section.

Utah Beach

Utah beach, the most westerly of the five beaches and the only one in Manche, was attacked by the US 4th Infantry Division. Due to navigational errors, the landings all took place on the south part of the beach which happened to be less well defended. Airborne troops landed through the night to secure the invasion’s western flank and to open the roads for their colleagues landing by sea at dawn. The objective was to cut the Cotentin Peninsula off from the rest of France and take the port of Cherbourg.

-

Dead Man's Corner Museum, 2 Village de l'Amont - 50500 Saint Come du Mont, +33 2 33 42 00 42. At the point where the 101st Airborne Division encountered the Green Devils (the German paratroopers) you can get an insight into the battle for Carentan on the site which has remained largely intact.

-

Musée Airborne (Airborne Museum), 14 rue Eisenhower - 50480 Sainte-Mère-Église, +33 2 33 41 41 35. The story of D-Day is told in pictures and mementos of the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. On display are a Douglas C-47, a Waco glider, a Sherman tank, several artillery pieces, vehicles, equipment, many small arms, uniforms and historic objects. Film. One of the best D-Day museums to strike a balance between an extensive collection of artifacts together with explanations and context. £2.85

.jpg/440px-Normandy_'10-_Ste_Mere_Eglise_La_Fiere_Bridge_(4823099763).jpg)

-

Sainte-Mère-Église. This is perhaps the most famous "D-day village" of all. Street panels around Ste Mère-Eglise explain the operations of the US paratroopers. In the square, a parachute effigy still dangles from the church, commemorating what happened to John Steele when his parachute snagged on the spire. Inside the church is a stained glass window featuring the Virgin and child, surrounded by paratroopers. Monuments in the area include the 82nd Airborne plate, 505th Parachute regiment stele, and Sainte-Mère-Église liberators stele.

-

Musée du Débarquement (Utah Beach Landing Museum), Ste Marie-du-Mont, (opposite the beach on the Utah site), +33 2 33 71 53 35. This museum uses film, documents and models to recall D-Day in a unique and innovative manner. Several armored vehicles, equipment and a landing ship are on display. £2.70

-

Monuments located by the Utah Beach Museum. American Soldier's Monument, 4th Infantry Division Monument, 90th Infantry Division Monument, VIIth Corps headquarters plaque, Coast Guard plaque, and US Navy plaque.

-

Batterie d’Azeville (Azeville Battery), La Rue - 50310 Azeville, +33 2 33 40 63 05. Near Ste Mère-Eglise, the Azeville Battery consisted of a dozen casemates, including four blockhouses with 105mm heavy guns, 350 m of underground tunnels, underground rooms and ammunition storage. The position was held by 170 German gunners. Guided tours of the Azeville battery offer insight into the German coastal defenses and the battle that took place here.

-

Musée de la Batterie de Crisbecq (Crisbecq Gun Battery Museum), Route des Manoirs, Saint-Marcouf, +33 6 86 10 80 59. The Crisbeq Gun Battery was one of the largest German coastal artillery batteries located on Utah Beach. There are 21 blockhouses linked by more than 1 km of trenches and restored recreation rooms, hospital, and kitchens.

-

Mémorial de la Liberté Retrouvée (Museum of Freedom Regained), 18, av de la Plage, 50310 Quinéville, +33 2 33 95 95 95. This museum recalls the French peoples daily life during the German occupation until the liberation.

The technical side

The war effort, including this invasion, got fine support from a range of scientists, engineers, technicians and workers in all the Allied countries. Some of the most important developments were:

.jpg/440px-LST-21_unloads_tanks_during_Normandy_Invasion,_June_1944_(26-G-2370).jpg)

- Landing Ship, Tank (LST). These ships were designed by the Americans, with some British input, and built mainly in the US. They were first used in North Africa, then in the invasions of Sicily and mainland Italy. On D-day, all the Allies used them. Most were manned by the US Navy.

- Radar. Between the two world wars, several countries researched this. Early in WW II the British had the most advanced systems and put them to good use in the Battle of Britain. Once the US entered the war, they were shown the British innovations and made some of their own. By the time of D-Day, Germany and Russia both had radar as well.

- Mulberry harbours. These were a British invention, prefabricated concrete caissons that could be towed across the Channel and sunk to create docks, breakwaters and so on for a temporary harbour. Two were built, one on the British #Gold Beach and one on the American #Omaha Beach, but the American one was destroyed by a storm.

- Hobart's Funnies. The amphibious DD tanks mentioned at #Site de Courseulles-sur-Mer and the flamethrower tank outside the #Musée Mémorial de la Bataille de Normandie in Bayeux were two of several types of unusual armour developed specifically for the Normandy landings. Others were designed for clearing minefields, for creating a bridge, or for destroying fortifications either by rolling up and planting explosive charges or by hammering them from a distance with a 230mm mortar.

The British general Percy Hobart was in charge of their design and crew training. On the day, he was in command of the 79th Armoured Division which provided the crews. They were used on all the beaches, and later in the war, supporting all the Allies. The British "Ultra" group at Bletchley Park broke nearly all the German codes used in this war and provided crucial intelligence to Allied field commanders.

Normandy campaign

The successful landing was a turning point in World War II, a major step toward the defeat of Nazi Germany; after D-Day, the Allies went on to liberate all of Europe. On the Western Front, the three main participants were the US, Britain and Canada. On the Eastern Front, Soviet forces continued to drive forward relentlessly as they had been doing since long before D-Day.

D-Day (June 6) was the start of a campaign in Normandy that lasted until late August. Those interested in wartime history may wish to visit the sites of the other main battles of that campaign, described below.

Meanwhile an attempt to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944 led to at least 7,000 arrests and almost 5,000 executions. Some of the plotters were senior officers and the repercussions greatly disrupted the German military. Among others, Rommel was forced into suicide.

Around Caen

Caen is symbolically important as the capital of the Calvados department and the largest city in Lower Normandy, and was strategically important as the transport hub of the region. The allies attacked it forcefully, and the Germans reinforced it heavily; at one point they had nine armored divisions plus infantry in and around the town.

The British and Canadians fought house-to-house in Caen itself and pressed hard in nearby areas, but did not gain full control of the town and environs until mid-July. By the end of the battle, much of the city was reduced to rubble and nearby villages were also heavily damaged.

The British and Canadians fought house-to-house in Caen itself and pressed hard in nearby areas, but did not gain full control of the town and environs until mid-July. By the end of the battle, much of the city was reduced to rubble and nearby villages were also heavily damaged.

The airfield at Carpiquet, just west of Caen, was one of the first Canadian objectives after D-Day, but it was defended by an entire SS panzer division plus other troops and the Canucks were beaten back. Both sides sent reinforcements and there was heavy fighting around the town until the Allies finally took it in early July.

- Ardenne Abbey, 49.1965°, -0.4139°. Twenty Canadian prisoners were shot by Waffen SS troops in the abbey courtyard in early June; over 150 Canadian prisoners were killed during the Normandy campaign. The regimental commander, Kurt Meyer, was using the Abbey as his headquarters at the time and was later convicted of war crimes.

Cotentin Peninsula

There was heavy fighting on the Cotentin Peninsula, west of the beaches, shortly after D-Day. The Allies urgently needed the port of Cherbourg at the tip of the peninsula, and sent an American force to take it.

The Americans faced quite a difficult fight; four German divisions were on the peninsula, and the bocage terrain there is largely unsuitable for tanks so a lot of hard foot slogging was required. Hitler, against his generals' advice, ordered German forces to defend the whole peninsula rather than withdrawing to strong positions around the city. They did that and made the Americans fight for every bit of ground, with heavy casualties on both sides.

The Americans faced quite a difficult fight; four German divisions were on the peninsula, and the bocage terrain there is largely unsuitable for tanks so a lot of hard foot slogging was required. Hitler, against his generals' advice, ordered German forces to defend the whole peninsula rather than withdrawing to strong positions around the city. They did that and made the Americans fight for every bit of ground, with heavy casualties on both sides.

Later Hitler commanded the defenders to fight to the last man, sacrificing themselves for the Fatherland. However when the situation became hopeless, General von Schlieben fought a delaying action while his troops demolished the port, then surrendered rather than let his remaining men die pointless deaths.

Cherbourg fell at the end of June; it was the first major French city liberated, and Caen the second.

After Cherbourg, the Americans turned south to take Saint-Lô at the base of the peninsula against stiff opposition; the town was thoroughly destroyed. Other units swept down the West side of the peninsula taking Coutances, Granville and Avranches.

American breakout

The American victories on the peninsula got them out into open territory more suited for tanks, and they then moved quickly in several directions.

The American victories on the peninsula got them out into open territory more suited for tanks, and they then moved quickly in several directions.

By this time nearly all German reserves had been committed in unsuccessful attempts to hold Caen and Saint-Lô, and many German formations had been badly chewed up. Some German units were tied down fighting the British and Canadians, four whole divisions had been wiped out by the Americans on the peninsula, and both the French Resistance and Allied bombing raids disrupted German efforts to bring in reinforcements. Also, the Germans were in quite deep trouble on the Eastern front, and they did not have anywhere near enough resources for both fronts.

The Americans had both more tanks and far better air support than the enemy; they used these advantages to full effect in a textbook example of fast-moving armoured tactics, similar to the blitzkrieg (lightning war) with which the Germans had devastated several countries a few years earlier. Part of the American force swung west to take Brittany with little resistance. Other units — most of the American force plus three British amoured divisions — moved south to Nantes and Angers on the Loire and east to Le Mans and Alençon, despite much more serious opposition.

In early August they took part in the battle around Falaise, and by the end of August they had liberated Paris.

Falaise

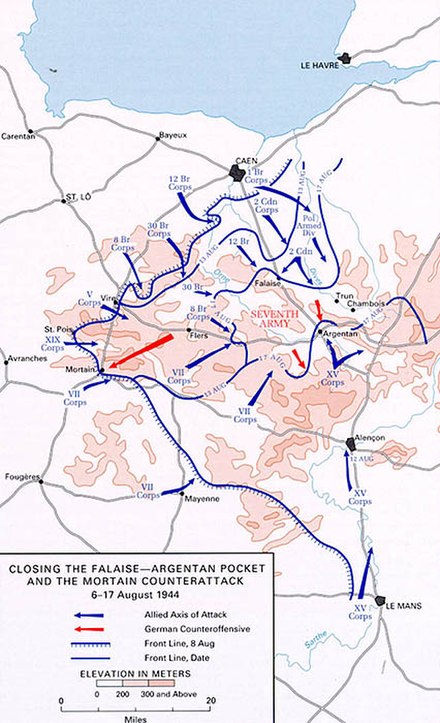

The decisive battle of the Normandy campaign was fought around Falaise, some distance inland of Caen, starting in early August.

Over 100,000 German troops were almost surrounded in the "Falaise Pocket". Commonwealth forces by now held everything around Caen on the north side and the British had taken the area around Vire on the west, while the rapid American advance had put them on the south side. Among other German forces, the pocket had those retreating after defeats in the intense battles for Caen, Saint-Lô and Vire. The Allies hammered them from the air and with artillery, pressed in with armour and infantry, and hoped to completely surround them by closing off the only exit, the "Falaise Gap" on the east.

Over 100,000 German troops were almost surrounded in the "Falaise Pocket". Commonwealth forces by now held everything around Caen on the north side and the British had taken the area around Vire on the west, while the rapid American advance had put them on the south side. Among other German forces, the pocket had those retreating after defeats in the intense battles for Caen, Saint-Lô and Vire. The Allies hammered them from the air and with artillery, pressed in with armour and infantry, and hoped to completely surround them by closing off the only exit, the "Falaise Gap" on the east.

To close the gap the Canadians, and the Polish armoured division deployed with them, thrust south near Falaise and Americans moved north in the Argentan area. However the by-now-desperate Germans fought hard to keep the gap open and escape through it; there was about two weeks of extremely heavy fighting before it was finally closed.

Falaise is a distinctly controversial battle; two decisions by the senior generals kept the Allies from closing the gap sooner and having an even larger victory:

- Patton's Americans were ordered to stop their advance and dig in near Argentan, rather than risk over-extending their lines by continuing north to join up with the Canadians. One reason for this was that the Allies knew from the code breakers at Bletchley Park that the Germans were planning an attack near Argentan.

- The British reserves were not sent to reinforce the Canadians who appealed urgently for them. These decisions were heatedly debated at the time; Patton and the Canadian generals were furious. Even with the benefit of hindsight, experts still disagree over whether they were sensible and prudent or foolish and costly.

The Canadians and Poles — unassisted on the ground, though they did get plenty of air support — could neither close the gap completely nor hold against German efforts to batter their way out; they did try and got quite badly mauled. There were many panzer divisions in the pocket; by now all were badly damaged but they could still mount devastating thrusts against chosen targets. The Canadians linked up with US forces on August 17th, closing the gap, but then the panzers smashed through and it was not until August 21st that the gap was closed for good.

On the German side, Hitler overruled the generals who wanted to conduct an orderly retreat early in the battle, ordering them instead to hold their ground and even mount counterattacks (the red arrows on the map). Most historians believe the generals were right, a German defeat was inevitable, and Hitler's interference only made it worse. In particular, ordering tanks withdrawn from the defense of Falaise for use in his counter-attacks allowed a Canadian advance.

The battle was utterly devastating to the countryside.

The battle was utterly devastating to the countryside.

Falaise was a major Allied victory; about 10,000 Germans were killed and 50,000 surrounded and forced to surrender; some did escape to fight on, but they lost nearly all their equipment and many were wounded. After Falaise, the Germans had no effective force west of the Seine and what troops they did have in the area were in full retreat; Paris was liberated only days later.

Overall result

The campaign in Normandy that began with D-Day and ended with Falaise was a major success for the Allies. Their losses were heavy — about 200,000 killed, missing, wounded or captured — but German losses were more than twice that. Both sides lost many tanks, guns, vehicles and other supplies, but at this stage of the war the Allies could better afford those losses.

After Normandy

After Normandy, Allied forces drove toward Paris from Normandy and the Pays de la Loire which the Americans had taken after breaking out of the peninsula. After Falaise, the German forces in the area were in severe disarray and the Allies still had air superiority so the advance was rapid. The German garrison in Paris surrendered on August 25.

After that, the British and Americans drove through eastern France and then into central Germany, aiming for Berlin. The Canadians took the left flank, liberating coastal parts of France, then Belgium, Holland and the North Sea coast of Germany.

In the last few days of the war a Canadian parachute battalion who had been among the first to land on D-Day were sent on a mad dash to take Wismar on Germany's Baltic coast, getting there just in time to prevent the Soviets from taking that region and possibly Denmark.

After Falaise and the liberation of Paris, the Germans regrouped and were able to put up a stiff resistance and even mount some counterattacks; the Allied advance slowed down, but it was unstoppable. Caught between the Russians on the east and the Western Allies on the west, losing on both fronts and being heavily bombed as well, Germany surrendered less than a year after D-Day, in early May 1945.

Cemeteries

Beautiful cemeteries overlook the sea and countryside and are essential stops along the way to understand and reflect on the human cost of the war. This was enormous; around 100,000 soldiers (about 60,000 German and 40,000 Allied) died in Normandy during the summer of 1944. There were also air, naval and civilian deaths, plus large numbers wounded or captured.

We list the cemeteries in two groups; the first four near the coast and the rest further inland. Order within each group is east-to-west.

-

Ranville War Cemetery, 5357 Rue du Comté Louis de Rohan Chabot, 49.23113°, -0.25776°. This cemetery has mainly men of the British 6th Airborne Division who made parachute and glider landings in the area on D-Day. There are 2,235 Commonwealth graves (the division had a Canadian battalion), plus 330 German and a few others.

-

Hermanville War Cemetery, 49.286°, -0.309°. This cemetery has 1,003 graves, mainly of British troops who fell in the first few days of the invasion.

-

Beny-sur-mer Canadian War Cemetery, 49.304°, -0.45°. Just over 2,000 Canadians are buried here; nearly all of them fell during the landings or shortly after. The cemetery is near the village of Reviers, about 18 km east of Bayeux.

_remembers_D-Day_(Image_3_of_7).jpg/440px-Flickr_-_DVIDSHUB_-_USACAPOC(A)_remembers_D-Day_(Image_3_of_7).jpg)

-

Normandy American Cemetery, 49.3591555°, -0.85316111°, +33 2 31 51 62 00. 09:00-18:00. Overlooking Omaha Beach, this 172.5 acre (70 hectare) cemetery contains the graves of 9,387 American soldiers. The rows of perfectly aligned headstones against the immaculate, emerald green lawn convey an unforgettable feeling of peace and tranquility. The beaches can be viewed from the bluffs above, and there is a path down to the beach. On the Walls of the Missing in a semicircular garden on the east side of the memorial are inscribed 1,557 names. Rosettes mark the names of those since recovered and identified.

-

Banneviile-la-Campagne War Cemetery, 49.1755°, -0.229°. This cemetery has 2,170 Commonwealth dead and five Poles. Most fell after the capture of Caen in mid-July.

-

Grainville-Langannerie Polish Cemetery, 49.0230°, -0.2706°. This is the only Polish war cemetery in France. It has the graves of 696 soldiers from the Polish armoured division who fought alongside the Canadians in Normandy; most fell in the fight around the Falaise Gap.

-

Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery, 49.06°, -0.292°. This cemetery is near Falaise and has 2871 Canadians, most of whom fell in the fight to close the Falaise Gap.

-

Saint Manvieu War Cemetery, 49.1780°, -0.5143°. This cemetery has 1,627 Commonwealth graves and 555 German. It is near the airport at Carpiquet and has mainly men who fell in the fierce battles over that.

-

Bayeux War Cemetery, 49.274°, -0.7143°. The largest British cemetery of the Second World War in France, containing the graves of over 4,400 Commonwealth soldiers, mostly British, and 500 others, mostly German. The Bayeux Memorial stands opposite the cemetery and bears the names of 1,808 Commonwealth soldiers who have no known grave. The cemetery is about a 15-minute walk from Bayeux train station. 2015-03-21

-

La Cambe German War Cemetery, 49.3428°, -1.0266°. This site has the graves of 23,400 German soldiers, most of whom fell in the Normandy campaign. See also the German government site.

-

Orglandes German War Cemetery, 49.426°, -1.449°. This cemetery has just over 10,000 German graves, including many who fell in the defense of the Cotentin Peninsula. German government site

Nearly all the dead in these cemeteries fell sometime between the invasion on June 6 and the end of the Falaise battle in mid-August.

Go next

From this area, one might go anywhere in France or across the channel to the UK. Normandy is a major tourist area with a range of attractions, as are nearby Brittany, the Pays de la Loire, and the Channel Islands.

Other places of possible interest to war buffs are the scenes of two Allied raids on the German-held French coast in 1942. A predominantly Canadian force attacked Dieppe, further north on the Normandy coast, and British commandos raided Saint-Nazaire, near Nantes to the south. Losses were extremely heavy in both places and arguably both raids were disasters, though the Saint-Nazaire attack did knock out an important drydock for the rest of the war. On the other hand, it is often claimed that these raids were essential preparation for D-Day, tests of German defenses that gave intelligence required for planning the invasion.

People interested in earlier history can see sites associated with Duke William IV of Normandy, who invaded England in 1066 and is known there as William the Conqueror. He was born in Falaise and is buried in Caen which was his capital; his castle is now a tourist attraction. His invasion fleet sailed from Bayeux and a museum there has a famous tapestry depicting his conquest of England.

.JPG/440px-B%C3%A9ny-sur-Mer_Canadian_War_Cemetery_(8).JPG)