Northern Ireland - part of the United Kingdom situated on the island of Ireland

Northern Ireland (Irish: Tuaisceart na hÉireann, Ulster Scots: Norlin Airlann) is part of the island of Ireland and one of the four constituent nations of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland has the Giant's Causeway (a world heritage site), stunning landscapes, vibrant cities, and welcoming locals interested in your own stories. The hit television series Game of Thrones was produced in Northern Ireland, which is also home to many of its filming locations.

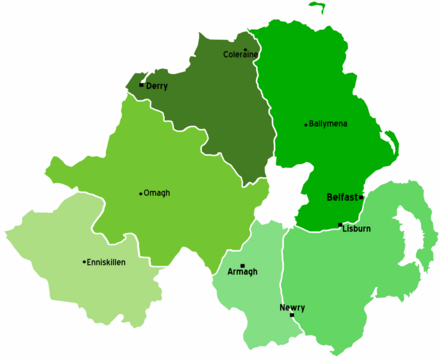

Counties

Walk in the footsteps of giants on the north coast, then ponder the tragedy of a giant ship in a museum in revived Belfast.

Drumlins (rounded glacial hills) spread across this county like a basket of eggs and in Armagh town two important cathedrals sit on drumlins.

Lively Derry with its intact walled town and a great Atlantic coast of big beaches and a cliff top temple.

A coastline of working fishing ports and strong currents at Strangford. The Mournes form the backdrop to the southern part of the county. East of Belfast, the Ulster Folk & Transport Museum houses a great collection of relocated buildings from across the region.

Drowned drumlins draw fishers and boaters in this lough landscape.

Walk off the beaten track in the windswept Sperrins and visit the great Ulster American Folk Museum

These counties are no longer units of government in Northern Ireland, but continue to have strong local identities and to cohere as travel destinations. They're regularly abbreviated as "Co." for instance "Co. Down" is County Down.

Cities and towns

- Belfast 📍 is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, with the major transport hubs and the best visitor facilities. West Belfast was torn by over 30 years of paramilitary and British Military conflict, which its sights reflect. The university area is cosmopolitan and houses a good regional museum. The docks have been revitalised by the Titanic Quarter, which houses a good museum about the Titanic. Dramatic views can be had from Divis and Black Mountain.

- Lisburn 📍 was the seat of Ireland's linen industry, depicted in its museum.

- Bangor 📍 is a large coastal town, was a seaside resort. Good base for the Ards Peninsula, home to the island's largest marina and good shopping.

- Armagh 📍 is the ecclesiastic capital of Ireland, for both the (Anglican) Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Church. Nearby Navan Fort is one of the most important ancient sites in Ireland. Home to many myths and legends.

- Coleraine 📍 on the River Bann in County Londonderry, 5 km from the sea, it has an impressive history dating back to Ireland’s earliest known settlers. Coleraine today is a major gateway to the popular Causeway Coast area. Coleraine is a good shopping town and also has a major performance theatre at the University of Ulster in the town.

- Derry, or Londonderry 📍 (Doire Cholmcille, "the Maiden City"), gateway to Donegal. Vibrant cultural life, intact city walls and the city where the Troubles started.

- Enniskillen 📍 is the picturesque main town of County Fermanagh, perfect for exploring the lakes around Lough Erne.

- Newry 📍 , most people visit the town for the shopping. Nearby is Slieve Gullion and the attractive village of Rostrevor. They somehow mislaid their entire castle in the back-end of a bakery.

- Omagh 📍 home to the very good Ulster American Folk Park, an outdoor museum of the story of emigration from Ulster to America in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Other destinations

- Causeway Coast 📍 in County Antrim has remarkable scenery, with the cascade of basalt columns at Giant's Causeway, the windswept bridge of Carrick-a-Rede, the Antrim glens, Dark Hedges, and wacky Gobbins. Bushmills is a venerable whiskey distillery, and there are crumbling castles, long sandy beaches and championship golf courses.

- Rathlin Island is Northern Ireland's only inhabited offshore island, reached by a short ferry ride.

- Mourne Mountains are criss-crossed by tracks past woodland up to the peaks: Slieve Donard at 852 m / 2796 ft is the highest in Northern Ireland.

- Lough Neagh at 51 square miles (392 km²) is the largest lake in Ireland and Britain, bordered by five of the six counties of Northern Ireland. It's popular for fishing and bird-watching.

Understand

History

Northern Ireland was created in 1921 when Ireland was partitioned by the Treaty that ended the Anglo-Irish war. Most of the island became what was initially called Southern Ireland then the Irish Free State and is now the independent Republic of Ireland or Eire. But six of the nine historic counties of Ulster remained within the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland, with the other three joining the south, and the plate tectonics of this rift are still in motion. "Ulster" is thus a geographical and cultural term, and doesn't refer to the political entity of Northern Ireland. Lots of outsiders do conflate the two, but doing so in nationalist company... well, if you're lucky, you'll just be thrown out of the pub. If you're unlucky, you'll be required to stay and listen to a history lesson that begins in the 12th century.

In the souvenir tea-towel version of Irish history, there were four provinces, Leinster, Munster, Connacht and Ulster, with a High King presiding over all. In reality in the early medieval period there were about a dozen kingdoms, forever warring and recognising no overlords. The northwest was O'Neill territory, while the northeast (now Antrim) was Ulaid hence "Ulster". From the 12th century the Normans settled in southeast Ireland but never got this far. Right up to the 17th century, Gaelic nobles ruled over Donegal, Derry and Tyrone. Then the English Tudors subdued this last redoubt and began to re-shape Ulster to their liking.

They did this by "plantations" - colonisation by settlers from Great Britain, with new towns laid out and industries such as linen, and modern methods of agriculture that needed fewer hands and displaced people from the land. This had long gone on the south, the difference with the Ulster plantations was that Great Britain was now predominantly Protestant, and especially the Scottish incomers. Rural Ireland was Roman Catholic, a religion ghettoised by the Penal Laws, so sectarian tensions were added to grievances over landholding, wealth and economic opportunity. Incomers and industry were strongest in the east, so Belfast grew into a metal-bashing second Glasgow, while the rural west was little developed and impoverished even before the famine years. A cultural crack developed across Ulster, especially visible in the city that one faction called Derry and the other Londonderry.

The 19th century campaign for Irish independence escalated into "The Troubles", which by 1920 entailed guerrilla warfare by the nationalists and savage reprisals by the British. This was resolved by the Treaty, which gave Ireland a grudging partial independence, but at the price of partition. "No surrender!" - no way would the Unionists of the north consent to be ruled from Dublin, which they feared would impose a priest-ridden, backward and anti-Protestant regime. So six counties remained in the UK, while the other three Ulster counties - Monaghan, Cavan and Donegal - joined the south, as they were Catholic and nationalist to a degree that no amount of gerrymandering could overcome.

Nationalist resentment festered but the late 20th century "Troubles" were stoked by economic downturn and blatant discrimination in Northern Ireland, and the new dynamic of civil rights. Police and army deployed "to separate warring communities" were clearly acting for only one side, and became targets for violence themselves. The flashpoint was on "Bloody Sunday" in Derry in 1972, when the army opened fire on an unarmed demonstration, killing 14. British rule lost its legitimacy, the republican or nationalist cause was strengthened, and both communities waged para-military or terrorist campaigns as there was nothing to be gained from conventional politics. The death toll during these years is reckoned at 3532: roughly 1840 civilians, 1050 police and soldiers, 370 Republican paramilitaries and 160 Loyalist paramilitaries. Perhaps 47,500 were injured.

.jpg/440px-Derry,_Northern_Ireland_(8001247960).jpg)

A series of short-lived political processes and peace accords came and went with no break in the violence; Belfast and Derry were scarred, with smoke rising, police patrolling in armoured cars, and army helicopters throp-thropping low. The "Good Friday Agreement" of 1998 also looked doomed when it was followed by the terrible Omagh bombing - yet after 20 years, this one has stuck. Violence dwindled, business and normal life returned, and Northern Ireland was able to re-launch itself as a tourist destination. Traffic nowadays criss-crosses from the Republic signalled only by a switch in road signs between km and miles per hour on the speed limits.

The GFA has held up for much the same reasons as the post-war French-German pact, which grew into the European Union - and that parallel is the present concern. "Don't mention the border", put both sides in each other's pockets, share power and let bygones be bygones, was the deal. But Brexit means that the Republic is now in the EU while Northern Ireland has left it - what the hell happens now? Nevertheless, the Brexit agreement has preserved the open border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and British and Irish citizens continue to have right of abode in each other's countries.

People

Most people visiting have heard of the varying allegiances of Northern Ireland's people. However, the people of Northern Ireland are friendly and warm towards visitors. You get the feeling that the people know the allegiances of each other, but it can be hard for visitors to ascertain.

Citizens can self-identify as Irish or British solely or Northern Irish. Similar divides exist in referring to places, for example the small city in the north west of the region on the banks of the River Foyle is Derry to Nationalists, while to Unionists it is Londonderry. Although Northern Irish people are British citizens from birth, they have the right to claim Irish citizenship and so may have an Irish passport in addition to or instead of a British passport.

Politics

.jpg/440px-Stormont_Parliament_Buildings_during_Giro_d'Italia,_May_2014(7).jpg) Northern Ireland has its own devolved legislature separate from Westminster, officially known as the Northern Ireland Assembly, but often referred to by the metonym Stormont after the estate in Belfast where its seat is located. There have traditionally been two major parties in Northern Ireland politics: the Nationalist Sinn Féin, whose policy platform is generally left-wing, and the Unionist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), whose policy platform is generally more right-wing. Another major party is the Alliance party, which is centrist. Some matters, such as foreign affairs and defence, continue to be under the purview of Westminster.

Northern Ireland has its own devolved legislature separate from Westminster, officially known as the Northern Ireland Assembly, but often referred to by the metonym Stormont after the estate in Belfast where its seat is located. There have traditionally been two major parties in Northern Ireland politics: the Nationalist Sinn Féin, whose policy platform is generally left-wing, and the Unionist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), whose policy platform is generally more right-wing. Another major party is the Alliance party, which is centrist. Some matters, such as foreign affairs and defence, continue to be under the purview of Westminster.

Climate

Like the rest of Ireland and Britain, the weather here is dominated by weather systems coming in from the Atlantic, this makes for wet and windy weather. In the west, annual rainfall is 2000mm and on the east coast it is 850mm. The sun does shine too, on the Co Down coast the annual average total of sunshine is 1450 hours. The best advice is to pack wet weather gear and footwear (unless you are content to stay indoors when those are needed) and to look regularly at weather forecasts, Met Office is a good one.

Talk

English is the official language, spoken and understood everywhere, though the rapid Ulster accent may be a struggle to follow. There are many dialect words the same as Scots, such as "aye" for yes and "wee" for small. "Crack" meaning news, gossip and merriment was likewise Scots but has taken on its Irish spelling "craic". The tell-tale word is "youse" for plural you: this is otherwise only heard in Glasgow, parts of Northern England and other communities with historic links to Ulster, while in the Republic you might hear "yiz".

English is the official language, spoken and understood everywhere, though the rapid Ulster accent may be a struggle to follow. There are many dialect words the same as Scots, such as "aye" for yes and "wee" for small. "Crack" meaning news, gossip and merriment was likewise Scots but has taken on its Irish spelling "craic". The tell-tale word is "youse" for plural you: this is otherwise only heard in Glasgow, parts of Northern England and other communities with historic links to Ulster, while in the Republic you might hear "yiz".

Irish or Gaeilge in both its standard and Ulster dialects (Canuint Uladh) is enjoying a revival. It's a Q-Celtic language akin to Scottish and Manx Gaelic, only distantly related to English, and in 2011 6% spoke it but only 0.2% used it as their everyday tongue. For a century it was shunned in the north: an Irish-speaker was either a poor Catholic potato-digger who'd failed to take the hint and push off to Liverpool, or the sort of quarrelsome (equals terrorist-suspect) nationalist who insists that Londonderry is called Derry. Irish is still only taught in Catholic schools and there are few avenues for adult learning, but it's increasingly used on signage and for official purposes, broadcast on BBC, and belatedly valued as part of Northern Ireland's culture.

Ulster Scots is an oddity - 1% spoke it according to the 2011 Census. Like Scottish Lallans it's on the cusp between being a dialect of English, a separate language, and an academic metro invention. The UK government has made unctuous pronouncements about its cultural relevance, which may be the kiss of death for its street cred, and it shares the problem of many "traditional" languages that have 27 different words for sheep-worming but need to borrow or invent words for cars, TVs and the internet. When written (which historically it wasn't) it looks like the signage at Schiphol Airport re-imagined by Hugh MacDiarmid. It seems likely to die out with the present generation.

Foreign languages are spoken by that nice couple from Hanover you sat by in the restaurant, and that student from Paris you met at the museum: they all seemed fluent in the foreign language of English. In Northern Ireland as in Great Britain, the older generation never learned (or saw the point of learning) other languages, while a younger generation did so but nowadays has fewer opportunities in Europe. However the barista population is unlikely to disappear, as many of them are eligible to acquire Irish passports and remain resident.

Get in

Immigration, visa, and customs requirements

Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom, so it has exactly the same entry requirements as England, Scotland and Wales.

- Citizens of the UK and Crown Dependencies can travel to Northern Ireland without a passport and have the automatic right to reside, work and take up benefits.

- Citizens of Ireland have the same entitlement as UK citizens.

- Citizens of other European Union countries do not require a visa for short visits (e.g. holiday, family visits, business meetings) but do require a visa for work or study in the UK. See Brexit for details.

- Citizens of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland have (and will probably continue to have) the same rules as for the EU.

- Citizens of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, South Korea, Taiwan, the United States and Uruguay do not require a visa for visits of less than 6 months.

- Most other countries will require a visa, which can be obtained from the nearest British Embassy, High Commission or Consulate.

- There is no passport control or border check between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. However visitors must carry any relevant documents that permit them entry to the UK, such as a passport or identity card and visa.

- The UK has a Working Holidaymaker Scheme for citizens of the Commonwealth of Nations and British dependent territories. This allows residency in the UK for up to 2 years, with limited working rights.

- There are restrictions in terms of goods one can bring from elsewhere in the UK to Northern Ireland and vice versa. Importing certain goods may incur tariffs. See the Brexit article and UK government website for more information.

For more information on these requirements, see the UK government's website.

By plane

Almost all direct flights to Northern Ireland are from UK, Western Europe and the Mediterranean. There are no flights from the Republic of Ireland, as the distances are too short.

George Best Belfast City Airport (IATA: BHD) is 2 miles east of Belfast city centre, with flights mainly from the UK. British Airways flies from London Heathrow, KLM from Amsterdam, and as of late 2023 Lufthansa from Frankfurt. All three destinations offer excellent global connections. There's a frequent bus to the city, or you can take the free shuttle bus to Sydenham railway station, see Belfast#Get in for details.

Belfast International Airport (IATA: BFS), also known as Aldergrove, is 20 miles west of Belfast. This has several UK connections and is the main airport for flights from Europe, mostly by EasyJet, Jet2, and Ryanair. There's a bus to Belfast city centre, and another between Lisburn and Antrim for transport elsewhere in Northern Ireland; see Belfast#Get in.

City of Derry Airport (IATA: LDY) has Ryanair flights from Liverpool and Edinburgh, and seasonally the Med. The airport is at Eglinton five miles east of Derry, with a bus to town.

Dublin Airport (IATA: DUB) is a good option for flights beyond Europe, eg the USA, and via the Gulf states. It's north of Dublin city on the main road north, with hourly buses to Newry and Belfast.

By train

From Dublin Connolly station the Enterprise Train runs eight times M-Sa and five on Sunday via Drogheda, Dundalk, Newry and Portadown to Belfast Lanyon Place. It doesn't serve Great Victoria Street station which is next to the Europa main bus station.

Other trains stop at several Belfast stations:

From Derry and Portrush hourly via Coleraine, Ballymena and Antrim (for Belfast International Airport) to Lanyon Place and Great Victoria Street.

From Portadown every 30 min via Lisburn and a dozen city stations, Sydenham (for Belfast City Airport) and Bangor.

From Larne hourly via Carrickfergus to Lanyon Place and Great Victoria Street.

By bus

Buses run hourly from Dublin city and airport to Belfast Europa station, taking 2 hr 20 min. There are competing operators, which holds the price down at €20 adult single and €30 return. Cross-border buses also run from Cavan and Monaghan to Armagh, Belfast and Coleraine, and from Letterkenny to Derry. Day-trip excursions from Dublin also visit Belfast.

Citylink / Ulsterbus 923 runs 2-3 times a day from Edinburgh via Glasgow, Ayr and the Cairnryan ferry to Belfast

National Express normally runs daily from London Victoria and Manchester via Cairnryan, but as of Oct 2021 this remain suspended, and they send you to Glasgow to join the Citylink - it might be easier to travel via Dublin.

By car

The M1 / N1 / A1 links Dublin to Belfast and there are multiple other crossing points from the Republic. There are no checks, and all you see at the border is a reminder northbound that speed limits are in miles per hour. Southbound you're offered a choice of speed limits in km/h or teorainneacha luais ciliméadair san uair. It's up to you to check that you're eligible to enter the UK (see above), that you have any necessary travel documents with you, and that your car insurance or rental agreement is valid for Northern Ireland - this should be automatic on any rental from the Republic.

By boat

Foot passengers should always look for through-tickets by bus / train and ferry, as these are considerably cheaper than separate tickets.

- From Cairnryan near Stranraer in Scotland, Stena Line sail to Belfast five times a day, 2 hr 15 min.

- Also from Cairnryan, P & O Ferries sail to Larne six times a day, 2 hr.

- From Birkenhead near Liverpool, Stena Line sail daily to Belfast, 8 hr.

- From the Isle of Man, IOM Steam Packet ferries sail to Belfast 4 days a week, taking just under 3 hr.

- Ferries sail to Dublin from Birkenhead, Holyhead (this is the quickest route from England), Isle of Man and the Continent. Dublin port is connected by tunnel to the motorway north, so motorists dodge the city centre traffic and reach Northern Ireland within 3 hours.

- From Campbeltown in Scotland a foot-passenger ferry sails April-Sept to Ballycastle then onward to Islay, returning in the afternoon. It's scheduled for day excursions but you can take a one-way trip. It didn't sail in 2021 and the 2022 schedule is TBA.

- From Greenore east of Dundalk in the Republic, a ferry crosses the opening of Carlingford Lough to Greencastle in County Down. It carries vehicles but only sails in summer, see Newry#Get in for details.

- From Greencastle in County Donegal, a ferry crosses the outlet of Lough Foyle to MacGilligans Point north of Derry. It likewise carries vehicles but only sails in summer, see County Londonderry#Get in.

Inland waterways are navigable all the way from Dublin and the Shannon up to Enniskillen and the Erne lakes, though you're not allowed to sail a hired boat that far. The other canals have been lost, though work is under way to rebuild the Ulster Canal around Monaghan.

Get around

By car

You don't need a car within Belfast or Derry, but will greatly benefit further out, such as along the Antrim glens.

You don't need a car within Belfast or Derry, but will greatly benefit further out, such as along the Antrim glens.

Many visitors bring their own car by ferry. Car hire is best arranged at the airports, as there is little availability in the cities, even in Belfast. Check whether you're also covered to drive in the Republic - this should be automatic on rentals, and vice versa for the north if you fly into Dublin and rent from there. Cross-border motoring is easy (and the obvious way to explore Donegal), but one-way rentals such as Belfast-Dublin incur stiff drop-off charges.

Motorway or equivalent fast dual carriageways have no tolls and fan out from Belfast to Newry and Dublin, Dungannon (for Omagh), Magherafelt (for Derry), Ballymena (for Antrim coast) and Larne (for glens). Their default speed limit is 70 miles per hour (112 km/h). Other main roads are usually 60 mph (96 km/h) out of town and 30 mph (48 km/h) in built-up areas. Road signage is identical to Great Britain's. The B-roads and back lanes are often narrow and twisty, with limited places to safely overtake, and sometimes little room for oncoming traffic to pass . . . and at this point you get a fright as some mad fellow blazes past with his hair on fire. Tradesmen's white vans drive at 18 or 80 mph and nothing in between. The worst speed bandits are the motorcyclists: Northern Ireland has a tradition of on-road motorbike circuits, which are risky enough under regulated sporting conditions, let alone when some boy racer with more throttle than skill decides to show off.

Newly qualified drivers in Northern Ireland must display "R" plates (for "restricted") for one year from gaining their licence. As with "L" plate learner drivers, they're limited to 45 mph (72 km/h) on all roads, to the exasperation of other motorists.

The days of tedious security checkpoints are gone, hopefully for good, but these still occur. The police are mostly looking for known local players and for EU smuggling (eg of fuel) and aren't much interested in tourists unless reeking of alcohol. The sooner you show your documents or whatever, the sooner they can send you on your way.

By bus and train

See also Rail travel in Ireland

Much of the public transport in Northern Ireland is under the umbrella of Translink. They offer a useful travel card called iLink, which gives you unlimited bus and train travel within specified zones for a day, week, or month. The card can be topped up if you decide to extend your trip.

For those places that happen to be linked by rail, that's usually the best option. Fares are inexpensive: a standard return from Belfast to Derry was £19 in 2021, and an off-peak day-trip was £17.33. Off-peak means after 09:30, giving you several hours to explore.

Buses fan out to all the main towns, and are frequent along the Causeway Coast of Antrim, and to Bangor and the upper Ards peninsula. They're infrequent further out, and the sights of interest may be some miles out from the town: you need your own wheels for Mourne Mountains, Strangford Lough, the Antrim Glens, the Londonderry Sperrins and coast, Tyrone or the Erne lakes.

By bicycle

If you are considering touring in Northern Ireland, it's worth considering buying the maps and guides produced by Sustrans to accompany the national routes they have helped develop. The routes can be found on Open Cycle Map, but Sustrans' guides are helpful for nearby places to stay or visit.

See

- Giant's Causeway is a , a dramatic cascade of basalt columns as the Antrim plateau reaches the sea.

- Carrick-a-Rede Bridge near Ballycastle was woven by fisherfolk to gain access to an islet with good salmon fishing. It's nowadays steel hawser not rope, but just as draughty across the chasm.

- Ulster American Folk Park is an open-air museum near Omagh in County Tyrone, depicting the story of emigration from Ulster to North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. There is an Old World section, the voyage itself, then emigrant life in the New World.

- Londonderry is a fascinating walled city and redoubt.

- Castles and mansions: Hillsborough and Newtownards have fine examples.

- Marble Arch Caves are part of the Global Geopark in the limestone terrain of Belcoo in County Fermanagh.

- Political murals are common in the "interface areas" where Protestant and Catholic neighbourhoods adjoin, so west Belfast and Derry have plenty. They're painted on gable walls of buildings and proclaim local allegiances. They come and go with political events - in 2014 one notable series in Strabane expressed solidarity with Palestine - so ask around if there are any examples worth tracking down.

Do

- Rugby union unites all the communities and is played on an all-Ireland basis, with players from Northern Ireland and the Republic turning out for the Irish national team. (Home internationals such as the Six Nations are staged in Dublin.) Ulster Rugby are the local professional team likewise drawn from Northern Ireland and from the three RoI counties of Ulster. They play in the United Rugby Championship (formerly known as Pro-14), the predominantly Celtic league, with their home ground at Ravenhill (sponsored as Kingspan Stadium) in Belfast.

- Football - soccer - is less developed, and the quality of the domestic league is low as nearly all the top Northern Irish footballers play for English clubs. Northern Ireland has its own national team, which has seen limited success - like other middle-order nations, it hopes to benefit from the enlarged format of tournaments such the UEFA Euro finals. The top club competition is the NIFL or Danske Bank Premiership of 12 teams. Linfield FC often win it - they and the national team play at Windsor Park in Belfast. Derry City is the only Northern Ireland club to play in the Republic's League of Ireland, where the playing season is April-Oct.

- Gaelic athletic games. Gaelic Football is played in Irish communities, from parish teams to county teams. County teams that win the Ulster championship get to play in the All Ireland championship. The ancient game of hurling and the female equivalent camogie are also play.

- Golf: lots and lots of courses. The championship course is Royal Portrush, hosting the Open in 2019 and next doing so in 2025.

- Motorbike racing was a big thing in Northern Ireland in the heyday of Joey Dunlop (1952-2000), but a series of tragedies has driven audiences and sponsorship away. The NorthWest 200 and Armoy Road Races are still held near Ballymoney in summer but the Dundrod and Clady races have folded.

- Learn Irish: the language is making a comeback. An Chultúrlann in west Belfast holds regular classes for all levels of ability and has Irish books and other learning materials.

- Orange Order Parades are a piece of living history, quintessential Northern Ireland, so catch one if you can. They wear their full-fig regalia and Carsonite bowler hats and strut down the street to the shrill of fife and tuck of drum. They are of course contentious: they symbolise Protestant and unionist dominance in the north, the lyrics of their tunes are anything but inclusive, and they have drawn (and gone looking for) trouble. However they're now regulated by the Parades Commission, which vets their route and won't let them march through neighbourhoods where they'd cause offence. The marching bands nowadays equivocate about their Protestant / Unionist roots, and bandy the word "community" a lot, though it's still a gutsy Catholic who would join one. The summer marching season culminates on the 12th of July, a public holiday commemorating the 1690 Battle of the Boyne which cemented Protestant hegemony in Ireland for the next 200 years - and for 300 in Northern Ireland. (When the 12th is a Sunday, the marches and holiday are on Monday 13th - this next occurs in 2026.) All the main towns have parades, and Belfast's is huge. Morning parades are peaceful because everyone's sober and knows their mothers are watching. Afternoon parades are like football crowds after a day in the pub, there may be alcohol-fuelled disorder; just use your common sense to swerve clear. For the full schedule of parades see the Commission website: they regulate all such events not just the Orange Order, but need not deliberate too long over the antique tractor rallies or Santa's Charity Sleigh.

Buy

- Money: the only official currency of Northern Ireland is the pound sterling. Bank of England and Bank of Scotland notes are legal tender and universally accepted (beware that the "Adam Smith" English £20 ceases to be valid after Sept 2022). The Northern Irish banks (AIB, Bank of Ireland, Danske Bank, and Ulster Bank) print their own notes, in common use here but grudgingly accepted in Great Britain and internationally, so trade them in before leaving. Ireland's euro is accepted in border areas but at the exchange rate do not rely on that save your euro for the Republic of Ireland and change your euro into pounds.

- Cross-border shopping is occasionally a feature when the £ / euro rate or tax difference (eg on fuel) becomes marked. In the early 21st century differences have been small, tending to draw shoppers in from the Republic rather than have Ulsterfolk sally out to Dundalk or Letterkenny. If you plan a cross-border trip, check ahead in case a bargain has emerged.

Eat

A popular dish is an assortment of fried food, called the "Ulster Fry". It consists of eggs, bacon, tomatoes, sausages, potato bread and soda bread. Some versions include mushrooms or baked beans. Fries are generally prepared as the name suggests, everything is fried in a pan. Traditionally lard was used, but due to health concerns, it has been replaced with oils such as rapeseed and olive. Historically, it was popular with the working class.

Some shops on the north coast close to Ballycastle sell a local delicacy called dulse. This is a certain type of seaweed, usually collected, washed and sun-dried from the middle of summer through to the middle of autumn. Additionally, in August, the lamas fair is held in Ballycastle, and a traditional sweet, called "yellow man" is sold in huge quantities. As you can tell from the name, it's yellow in colour, it's also very sweet, and can get quite sticky. If you can, try to sample some yellow man, just make sure you have use of a toothbrush shortly after eating it... it'll rot your teeth!

The cuisine in Northern Ireland is similar to that in the United Kingdom and Ireland as a whole, with dishes such as fish and chips a popular fast food choice. Local dishes such as various types of stew and potato-based foods are also very popular. 'Champ' is a local speciality consisting of creamed potatoes mixed with <abbr title="spring onions">scallions</abbr>.

With the advent of the peace process, the improvements in economic conditions for many people in Northern Ireland, there has been a great increase in the number of good restaurants, especially in the larger towns such as Belfast and Derry. Indeed it would be difficult for a visitor to either of those cities not to find a fine-dining establishment to suit their tastes, and wallet.

There is a strong emphasis on local produce. Locally produced meats, cheeses and drinks can be found in any supermarket. For the real Northern Irish experience, sample Tayto brand cheese and onion flavoured crisps: these are nothing short of being a local icon and are available everywhere.

Drink

The legal drinking age in Northern Ireland is 18. Those of 16-17 may be served beer and wine with meals if accompanied by a sober adult. Pubs are normally open Su-Th until 23:00 and F Sa to 01:00, but in 2020 and 2021 they've had curtailed hours.

The legal drinking age in Northern Ireland is 18. Those of 16-17 may be served beer and wine with meals if accompanied by a sober adult. Pubs are normally open Su-Th until 23:00 and F Sa to 01:00, but in 2020 and 2021 they've had curtailed hours.

- Bushmills Whiskey is made in that Antrim north coast town. The distillery tours are very much on the tourist circuit as it's close to Giant's Causeway.

- Guinness: it's a Marmite thing, you either like the burnt flavour or you don't, and there's no shame in not liking it. It's just as popular in Northern Ireland as in the Republic, and the Guinness family were famously Protestant. But Guinness established such commercial dominance that other breweries struggled, and it was easier to find continental beers in Northern Ireland than anything brewed locally. Micro- and craft breweries are now appearing - they're described for individual towns so try their products, but few offer tours. One that does is Hilden in Lisburn.

- Belfast Distillery is nowadays just a retail park, recalled in several street names. There are plans to convert cells within the former Crumlin Road jail into a whiskey distillery, but in 2021 the only spirits you might encounter are the unquiet dead on the jail's "paranormal tours". Belfast Artisan Distillery makes gin several miles north at Newtownabbey, no tours.

- Echlinville Distillery in Kircubbin south of Newtownards produce whiskey, which first came to market in 2016; no tours.

- Niche Drinks in Derry produce a blended whiskey, but their main line is cream liqueurs, Irish coffee and the like; no tours.

Stay safe

Northern Ireland has changed greatly in the years since the peace agreement was signed in 1998, though its troubles have not entirely ceased. There remains a high frequency of terrorist incidents in Northern Ireland, with the UK Home Office defining the current threat level as 'severe'. Tourists, however, are not the target of such terrorist incidents and therefore are highly unlikely to be affected. There is a significant risk of disruption caused by incidents of civil unrest during the contentious 'marching season' which takes place each year over the summer months. The U.S. State Department (dead link: January 2023) advises visitors to Northern Ireland to remain 'alert' during their visit and to keep themselves abreast of political developments.

Northern Ireland has changed greatly in the years since the peace agreement was signed in 1998, though its troubles have not entirely ceased. There remains a high frequency of terrorist incidents in Northern Ireland, with the UK Home Office defining the current threat level as 'severe'. Tourists, however, are not the target of such terrorist incidents and therefore are highly unlikely to be affected. There is a significant risk of disruption caused by incidents of civil unrest during the contentious 'marching season' which takes place each year over the summer months. The U.S. State Department (dead link: January 2023) advises visitors to Northern Ireland to remain 'alert' during their visit and to keep themselves abreast of political developments.

Most visits to Northern Ireland, however, are trouble-free, and visitors are unlikely to frequent the areas that are usually affected by violence. Northern Ireland has a significantly lower crime rate than the rest of the United Kingdom, with tourists being less likely to encounter criminality in Belfast than any other UK capital.

Northern Ireland has one of the lowest crime rates among industrialised countries. According to statistics from the U.N. International Crime Victimisation Survey (ICVS 2004), Northern Ireland has one of the lowest crime rates in Europe, lower than the United States and the rest of the United Kingdom, and even during the Troubles, the murder rate was still lower than in most large American cities (although this does not take into account the vastly lower population figures). The latest ICVS show that Japan is the only industrialised place safer than Northern Ireland. Almost all visitors experience a trouble-free stay.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (formerly the Royal Ulster Constabulary or RUC) is the police force in Northern Ireland. Unlike the Garda Síochána in the Republic, the PSNI are routinely armed with handguns and/or long arms. The police still use heavily-armoured Land Rover vehicles; do not be concerned by this, as it doesn't mean that trouble is about to break out. There is a visible police presence in Belfast and Derry, and the police are approachable and helpful. Almost all police stations in Northern Ireland are reinforced with fencing or high, blast-proof walls. It is important to remember that there is still a necessity for this type of protection and that it is a visible reminder of the province's past.

As with most places, avoid being alone at night in urban areas. In addition, avoid wearing clothes that could identify you, correctly or not, as being from one community or the other, for example Celtic or Rangers football kits. Do not express a political viewpoint (pro-Nationalist or pro-Unionist) unless you are absolutely sure you are in company that will not become hostile towards you for doing so. Even then, you should be sure that you know what you're talking about. It would be even better to act as if you either don't know about the conflict or don't care. Avoid political gatherings where possible. Many pubs have a largely cultural and political atmosphere (such as on the Falls Road, the mostly Nationalist main road in West Belfast, and the Newtownards Roads in predominantly Unionist East Belfast), but expressing an opinion among good company, especially if you share the same view, will usually not lead to any negative consequences. People are generally more lenient on tourists if they happen to say something controversial, and most will not expect you to know much about the situation.

Traffic through many towns and cities in Northern Ireland tends to become difficult at times for at least a few days surrounding the 12th July due to the Orange Parades and some shops may close for the day or for a few hours. The parades have been known to get a bit rowdy in certain areas but have vastly improved. Additionally, the last Saturday in August is known as "Black Saturday" which is the end of the marching season. Trouble can break out without warning, though locals or Police officers will be more than happy to advise visitors on where to avoid. The Twelfth Festival in Belfast is being re-branded as a tourist-friendly family experience and efforts are being made to enforce no-alcohol rules aimed at reducing trouble.

Pickpockets and violent crime are rare so you can generally walk around the main streets of Belfast or any other city or town without fear during the day.

Stay healthy

There are no COVID-related restrictions in place in Northern Ireland; however, the government recommends the wearing of a mask in indoor public places, such as shops, cafes, pubs and venues, and in health and social care settings like hospitals and care homes.

For the most up-to-date information:

- Northern Ireland Government coronavirus portal

- Health and Social Care (HSC) Board

- Public Health Agency

Connect

To dial Northern Ireland from outside the UK or Republic (or from a "foreign" phone whilst there), dial +44 28.

From Great Britain dial the area code 028, with no country code. From within Northern Ireland, just dial the number with no country or area code.

From the Republic, dial the area code 048, with no country code; +44 28 also works but is charged at international rates. There isn't a reciprocal arrangement, so to call the Republic from Belfast it's +353 then the area code (such as 1 for Dublin) same as if you called from Belgrade.

International phone cards are widely available in large towns and cities within Northern Ireland, and phone boxes accept payment in GBP£ and Euro. You can also buy a cheap pay as you go phone from any of the phone networks.

Northern Ireland has the same mobile networks as Great Britain: EE, O2, Three and Vodafone. The towns and main highways have coverage from all of them, often with 4G, but the signal is patchy out in the country lanes. O2 has somewhat wider coverage than the others; see individual pages for details. As of Oct 2021, there's 5G in Belfast but not beyond. Wifi is widely available in public places.

Using a Northern Ireland or other British phone in the Republic may incur EU roaming charges, and vice versa for Irish phones used in the north. Areas within five miles of the border (such as Derry) pick up both countries' networks, so take care your mobile doesn't switch. The Irish carriers are eir Mobile, Three Mobile and Vodafone Mobile, so check which version of Vodafone you're on.

Respect

The province's troubled past has created a uniquely complex situation within Northern Ireland's society. Integration, or even interaction, between the two main religious groups varies hugely depending on where you are: for example, in affluent South Belfast or Bangor, those from Catholic and Protestant backgrounds live side by side, as they have for generations, whereas in West Belfast, the two communities are separated by a wall.

The province's troubled past has created a uniquely complex situation within Northern Ireland's society. Integration, or even interaction, between the two main religious groups varies hugely depending on where you are: for example, in affluent South Belfast or Bangor, those from Catholic and Protestant backgrounds live side by side, as they have for generations, whereas in West Belfast, the two communities are separated by a wall.

If you are not British or Irish, the main thing to avoid is pontificating about the situation or taking one particular side over the other. Local people do not appreciate it and you will surely offend someone. Comments from outsiders will likely be seen as arrogant and ill-informed. This applies particularly to Americans (or others) who claim Irish ancestry and may therefore feel they have more of a right to comment on the situation (the majority of people in Northern Ireland would beg to differ). A good rule of thumb is simply to keep your opinions to yourself and avoid conversations that might be overheard.

Generally speaking, people from Northern Ireland are welcoming, friendly and well-humoured people, and they will often be curious to get to know you and ask you why you're visiting. However that does not mean that, on occasion, there are no taboos. Avoid bringing up issues like the IRA, UVF, UDA, INLA, or political parties, as it will not be appreciated. Other than that, there are no real dangers to causing tension among the Northern Irish people. As with virtually all cultures, don't do anything you wouldn't do at home.

Foreign nationals claiming they are ‘Irish’ just because of an ancestor will likely be met with amusement, although this may become annoyance or anger should they then express their views related to The Troubles.

Unlike in parts of Europe, there is no social taboo associated with appearing drunk in bars or public places. Though it is advisable to avoid political conversations in general, this is particularly true when alcohol is involved. People from all backgrounds congregate in Belfast city centre to enjoy its nightlife; avoiding political discussions is an unwritten rule.

On a related note, do not try to order an Irish Car Bomb or a Black and Tan. Some establishments will refuse to serve it to you if you use those names. More acceptable names are an Irish Slammer or a half-and-half.

Also, Northern Irish people have a habit of gently refusing gifts or gestures you may offer them. Do not be offended, because they really mean that they like the gesture. Also, you are expected to do the same, so as not to appear slightly greedy. It is a confusing system but is not likely to get you in trouble.

Tours of Belfast often include a visit to the Peace Lines, the steel barriers that separate housing estates along sectarian lines. These are particularly visible in West Belfast. It is common for private or taxi tours to stop here and some tourists take the opportunity to write messages on the wall. It is important to remember that there is a real reason why these barriers have not been removed, and that they provide security for those living on either side of them. Messages questioning the need for these security measures, or those encouraging the residents to 'embrace peace' etc., are not appreciated by members of the community who live with the barriers on a day-to-day basis, and such behaviour is generally regarded as arrogant and patronising.

The terms which refer to the two communities in Northern Ireland have changed. During the Troubles, the terms 'Republican' and 'Loyalist' were commonplace. These are seen as slightly 'extreme', probably because they were terms used by the paramilitaries. It is more common to use the terms 'Nationalist' and 'Unionist' today; these terms are more politically neutral. 'Loyalist' and 'Republican' still refer to particular political viewpoints.

Unionists tend to identify as British, and may be offended if referred to as Irish. Conversely, Nationalists tend to identify as Irish, and may find it offensive if referred to as British. If you are not sure about someone's political leanings, it is best to just use the term "Northern Irish" until you are prompted to do otherwise.

Naming

A number of politically-charged names for Northern Ireland are used by some residents, the most contentious being "The Six Counties" (used by Nationalists) and "Ulster" (used by Unionists to refer only to NI). Visitors are not expected to know, or use, these or any other politically-sensitive terms, which will only be encountered if you choose to engage in political discussions.

Should it be necessary to refer to Northern Ireland as either a geographical or political entity, the term "Northern Ireland" (at least, when used by people from outside Ireland) is accepted by the vast majority of people.

If you need to refer to Ireland as a geographical whole, a reference to "the island of Ireland" or "all-Ireland" has no political connotations, and will always be understood.

Visitors might be more aware that the second city of Northern Ireland has two English-language names, "Londonderry" (official) and "Derry" (used by the local government district and on road signs in the Republic). Nationalists, and everyone in the Republic, will invariably use the name "Derry", whereas Unionists strongly prefer "Londonderry". It is wise not to question anyone's use of either name over the other, and if you are asked "Did you mean Derry" or "Did you mean Londonderry?" you should politely say yes.

It may all seem confusing, but Northern Irish people won't expect you to know or care about every detail of the situation and, as mentioned above, will openly welcome you to their country. Young people tend to be more open-minded about it all and are much less politically motivated than their parents or grandparents.

Social issues

The people in Northern Ireland are generally warm and open, always ready with good conversation. Of course, being such a small, isolated country with a troubled past has also led to a decidedly noticeable lack in social diversity.

The majority of people you will encounter will be white. It isn't unusual to go a few days without encountering any multiculturalism, apart from other visitors or Chinese restaurants. This will make quite a change if you are from multicultural countries.

Racism is not generally an issue; however, due to the openness and rather frank humour in Northern Ireland, small, sarcastic comments may be made about the issue, in jest, if a local encounters someone outside of his or her own nationality. It is best not to react to this, as it is most likely just a joke, and should be treated as such. In Northern Ireland, a "mixed marriage" refers to a Catholic marrying a Protestant.

Some citizens of Northern Ireland are not the most accepting when it comes to homosexuality. While a small and dwindling minority, fundamentalist Christians hold greater political sway in Northern Ireland than almost anywhere else in western Europe. Homophobic crimes are rare but still more common than in the rest of the UK and Ireland. There are virtually no examples of any gay and lesbian communities outside Central Belfast. However, parts of the capital (for example the University Quarter) are perfectly safe and accepting of gay and lesbian people, with both of Belfast's universities incorporating active LGBT societies. Same-sex marriage was legalised in 2020 and a ban on conversion therapy is due to come into force later in 2021.

There have been issues of more severe racism in parts of the province. Belfast is the most ethnically diverse area, but even so the city is over 97% white. Typically, incidents of racism have been confined to South Belfast, which has a higher mix of non-white ethnicities due to its location near Queen's University. After decades of little or no immigration, some people find it hard to accept outsiders moving in, and racist attacks are usually on an immigrant's property, rather than the immigrants themselves.

Go next

- The Republic of Ireland is quickly reached in any direction but north; Dublin is within a day trip but deserves much longer.

- Scotland is visible across the North Channel. Glasgow especially has strong links to Ulster.

- The Isle of Man is the clod of earth that Finn McCool hurled in the general direction of his foe Bennandonner. You may have to travel via Dublin to reach it.