For other places with the same name, see Poland (disambiguation).

Poland (Polish: Polska) is a Central Europe country that has, for the last few centuries, sat at the crossroads of three of Europe's great empires. As a result, it has a rich and eventful history, and a strong basis for its booking tourism industry.

Poland (Polish: Polska) is a Central Europe country that has, for the last few centuries, sat at the crossroads of three of Europe's great empires. As a result, it has a rich and eventful history, and a strong basis for its booking tourism industry.

Its heritage is reflected in its architecture, museums, galleries and monuments. Its landscape is varied, and extends from the Baltic Sea coast in the north to the Tatra Mountains in the south. In between, lush primeval forests are home to fascinating species of animals including bisons in Białowieża; beautiful lakes and rivers for various water-sports, the best known of which are in Warmińsko-Mazurskie; rolling hills; flat plains; and deserts. Among Poland's cities you can find the perfectly preserved Gothic old town of Toruń, Hanseatic heritage in Gdańsk and evidence of the 19th-century industrial boom in Łódź.

Today's Poland has a very homogeneous society in terms of ethnicity, language and religion. The historical Republics of Poland, whose boundaries were very different from those of today, were very multi-cultural, and, for a period, Poland was known as Europe's most religiously tolerant. Poland held Europe's largest Jewish population, which was all but wiped out by the Holocaust of World War II and after the war by the anti-Semitic communist government.

Poland's western regions, including large parts of Lower Silesia, Lubuskie and Zachodniopomorskie, were parts of neighbouring Germany at different periods of time. The natural border of mountain ridges separating Poland from its southern neighbours, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, did not stop the cultural influence (and periodic warring). In the Middle Ages, Poland was part of a powerful Commonwealth with Lithuania that governed much of today's Belarus and Ukraine. The cultural evidence of it can be found closer to the present-day borders. Lastly, the entire eastern half of Poland used to be controlled by the Russian Empire, and there was a strong Soviet influence during the communist era, leaving behind many traces in both culture and built heritage.

Despite losing a third of its population, including a disproportionally large part of its elites, in World War II, and suffering many economic setbacks as a Soviet satellite state afterwards, Poland in many ways flourished culturally in the 20th century. Paving the way for its fellow Eastern bloc states, Poland had a painful transition to democracy and capitalism in the late 1980s and 90s. In the 21st century, Poland joined the European Union and has enjoyed continuous economic growth unlike any other EU country. This has allowed it to markedly improve its infrastructure and had a profound effect on its society. Creative and enterprising, Poles continually come up with various ideas for events and festivals, and new buildings and institutions spring up almost before your eyes, so that every time you come back, you are bound to discover something new.

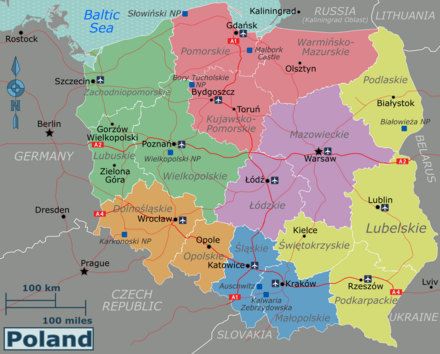

Regions

regions are called województwa, abbreviated "woj.". The word is translated as voivodeship or province.

Central Poland (Łódzkie, Mazowieckie)

Central Poland is focused on the capital city of Warsaw, and Łódź which has a rich textile manufacturing and film-making heritage

Southern Poland (Małopolskie, Śląskie)

Home to spectacular mountain ranges, the world's oldest operating salt mines, fantastic landscapes, caves, historical monuments and cities. The magnificent medieval city of Kraków is Poland's most-visited destination.

Southwestern Poland (Dolnośląskie, Opolskie)

Colorful mixture of different landscapes. One of the warmest regions in Poland with the very popular, dynamic city of Wrocław. Within this region you will find Polish, German and Czech heritage.

Northwestern Poland (Lubuskie, Wielkopolskie, Zachodniopomorskie)

A varied landscape, profusion of wildlife, bird-watcher's paradise and inland dunes. Its heritage is shaped by centuries as part of Germany.

Northern Poland (Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Pomorskie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie)

Home to Poland's attractive seaside; sandy beaches with dunes and cliffs; lakes, rivers and forests.

Eastern Poland (Lubelskie, Podkarpackie, Świętokrzyskie, Podlaskie)

Very green area filled with lakes. It offers unspoiled nature and the possibility of camping in beautiful countryside. Unique primeval forests and picturesque rivers (e.g. Biebrza river) with protected bird species make the region increasingly interesting for tourists.

Cities

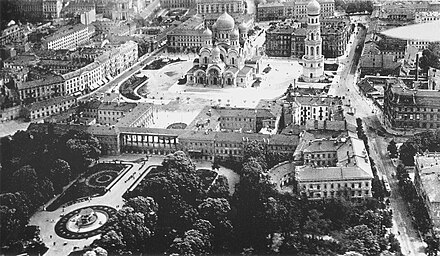

- Warsaw 📍 (Warszawa) — capital of Poland, and one of the EU's thriving new business centres; the old town, nearly completely destroyed during World War II, has been rebuilt in a style inspired by classicist paintings of Canaletto.

- Gdańsk 📍 — the former German city of Danzig is one of the old, beautiful European cities, rebuilt after World War II. It is a great departure point to the many sea resorts along the Baltic coast.

- Katowice 📍 — central district of the Upper Silesian Metropolis, both an important commercial hub and a centre of culture.

- Kraków 📍 — the "cultural capital" of Poland and its historical capital in the Middle Ages; its centre is filled with old churches, monuments, the largest European medieval market-place - and now with trendy pubs and art galleries. Its city centre is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Lublin 📍 — the biggest city in Eastern Poland, it has a well-preserved old town with typical Polish architecture, along with unusual Renaissance elements.

- Łódź 📍 — once renowned for its textile industries, the "Polish Manchester" has the longest walking street in Europe, Piotrkowska Street, full of picturesque 19th-century architecture.

- Poznań 📍 — the merchant city, considered to be the birthplace of the Polish nation and church (along with Gniezno); presents a mixture of architecture from all epoques.

- Szczecin 📍 — the most important city of Pomerania with an enormous harbour, monuments, old parks and museums.

- Wrocław 📍 — an old Silesian city with great history; built on 12 islands, it has more bridges than any other European town except Venice, Amsterdam and Hamburg.

Other destinations

- Auschwitz-Birkenau 📍 — An infamous complex of German Nazi extermination and slave labour camps that became the centre of the Holocaust of Jews during World War II. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Białowieża National Park 📍 — a huge area of ancient woodland straddling the border with Belarus. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Bory Tucholskie National Park 📍 — national park protecting the Tucholskie Forests.

- Kalwaria Zebrzydowska 📍 — monastery in the Beskids from 1600 with Mannerist architecture and a Stations of the Cross complex. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Karkonosze National Park 📍 — national park in the Sudety around the Śnieżka Mountain with beautiful waterfalls.

- Malbork 📍 — home to the Malbork Castle, the beautiful huge Gothic castle made of brick and the largest one in Europe. UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Słowiński National Park 📍 — national park next to the Baltic Sea with the biggest dunes in Europe.

- Wieliczka Salt Mine 📍 — the oldest still existing enterprise worldwide, this salt mine was exploited continuously since the 13th century. A UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Wielkopolski National Park 📍 — national park in Greater Poland protecting the wildlife of the Wielkopolskie Lakes.

Understand

History

Early history

See also: Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The first cities in today's Poland, Kalisz and Elbląg on the Amber Trail to the Baltic Sea, were mentioned by Roman writers in the first century AD, but the first Polish settlement in Biskupin dates even further back to the 7th century BC.

The first cities in today's Poland, Kalisz and Elbląg on the Amber Trail to the Baltic Sea, were mentioned by Roman writers in the first century AD, but the first Polish settlement in Biskupin dates even further back to the 7th century BC.

Poland was united as a country in the first half of the 10th century, and adopted Catholicism as the state religion in 966 AD. The first capital was the city of Gniezno, but a century later the capital was moved to Kraków, where it remained for half a millennium.

Poland experienced its golden age from 14th to 16th century, under the reign of King Casimir the Great, and the Jagiellonian Dynasty, whose rule extended from the Baltic to the Black and Adriatic seas. In the 16th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Europe; the country attracted many immigrants, including Germans, Jews, Armenians and Dutch, because of the freedom of confession guaranteed by the state and the atmosphere of religious tolerance, which was exceptional in Europe at the time of the Holy Inquisition.

Under the rule of the Vasa Dynasty, the capital was moved to Warsaw in 1596. During the 17th and the 18th centuries, the nobility increasingly asserted its independence from the monarchy; combined with several exhausting wars, this greatly weakened the Commonwealth. Responding to the need for reform, Poland was the first country in Europe (and the second in the world, after the US) to pass a constitution. The constitution of May 3, 1791 was the key reform among many progressive but belated attempts to strengthen the country during the second half of the 18th century.

Partitions and regaining independence

With the country in political disarray, various sections of Poland were occupied by its neighbors — Russia, Prussia and Austria — in three coordinated "partitions" of 1772 and 1793, and 1795. After the last partition and a failed uprising, Poland ceased to exist as a country for 123 years.

However, this long period of foreign domination was met with fierce resistance. During the Napoleonic Wars, a semi-autonomous Duchy of Warsaw arose, before being erased from the map again in 1813. Further uprisings ensued, such as the 29 November uprising of 1830-1831 (mainly in Russian Poland), the 1848 Revolution (mostly in Austrian and Prussian Poland), and 22 January 1863. Throughout the occupation, Poles retained their sense of national identity, and kept fighting the subjugation of the three occupying powers.

Poland returned to the map of Europe with the end of World War I, regaining its independence on November 11, 1918. In 1920–21, the newly-reborn country got into territorial disputes with Czechoslovakia and, especially, the antagonistic and newly Soviet Russia with which it fought a war. This was further complicated by a hostile Weimar Germany to the west, which strongly resented the annexation of portions of its eastern Prussian territories, and the detachment of German-speaking Danzig (contemporary Gdańsk) as a free city.

World War II

World War II in Europe began with a coordinated attack on Poland's borders by the Soviet Union from the east and Nazi Germany from the west and north. Only a few days prior to the start of the war, the Soviet Union and Germany had signed a secret pact of non-aggression, which called for the re-division of the central and eastern European nations. Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939 and the Soviet Union attacked Poland on 17 September 1939, effectively starting the fourth partition. These harmonised invasions caused the re-established Polish Republic to cease to exist. Hitler used the issue of Danzig (Gdańsk) as a pretext to invade Poland, much as he used the "Sudetenland Question" to conquer Czechoslovakia.

Many of World War II's most infamous war crimes were committed by the Nazis and Soviets on Polish territory, with the former committing the majority of them. Polish civilians opposed to either side's rule were ruthlessly rounded up, tortured, and executed. Nazi Germany established concentration and extermination camps on Polish soil, where many millions of Europeans — including about 90% of Poland's long-standing Jewish population and thousands of local Romanies (Gypsies) — were murdered; of these Auschwitz is the most infamous. The Nazis murdered about three million Polish Jews and about the same number of Polish non-Jews — not only people who actively opposed the Nazi occupation, but also people more or less randomly rounded up. Part of the Nazis' strategy was to attempt to annihilate all Polish intelligentsia and potential future leadership, the better to absorb Poland into Germany, so thousands of Polish Catholic priests and intellectuals were summarily murdered. For their part, the Soviets rounded up and executed the cream of the crop of Polish leadership in the part of Poland they occupied in the Katyń Massacre of 1940. About 22,000 Polish military and political leaders, business owners, and intelligentsia were murdered in the massacre, approved by the Soviet Politburo, including by Joseph Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria. The Soviets also murdered about 150,000 ordinary Poles and deported another 1,700,000 to Siberia between 1939 and 1941.

Because of World War II, Poland lost about 20% of its population, the Polish economy was completely ruined, and nearly all major cities were destroyed. After the war Poland was forced to become a Soviet satellite country, following the Yalta and Potsdam agreements between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. To this day these events are viewed by many Poles as an act of betrayal by the Allies. Poland's territory was significantly reduced and shifted westward to the Oder-Neisse Line at the expense of defeated Germany. The native Polish populations from the former Polish territories in the east, now annexed by the Soviet Union, were expelled by force and replaced the likewise expelled German populations in the west and in the north of the country. This resulted in the forced uprooting of over 10 million people and delayed Polish-German reconciliation. See Cold War Europe for context.

Communism (People's Republic of Poland)

After the bloody Stalinist era of 1945–1953, Poland was comparatively tolerant and progressive in comparison to other Eastern Bloc countries. But strong economic growth in the post-war period alternated with serious recessions in 1956, 1970, and 1976 which resulted in labour turmoil over dramatic inflation and shortages of goods. Ask older Poles to tell you about the impoverished Poland of the Communist era and you'll often hear stories of empty store shelves where sometimes the only thing available for purchase was vinegar. You'll hear stories about back room deals to get meat or bread, such as people trading things at the post office just to get ham for a special dinner, or religious services held secretly in basements.

A brief reprieve from this history occurred in 1978. The then-archbishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected as Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, taking the name John Paul II. This had a profound impact on Poland's largely Catholic population, and to this day John Paul II is widely revered in the country.

In 1980, the anti-communist trade union, "Solidarity" (Polish: Solidarność), became the major driving force in a strong opposition movement, organizing labor strikes, and demanding freedom of the press and democratic representation. The communist government responded by imposing martial law from 1981 to 1983. During this period, the country again suffered from widespread poverty, thousands of people were detained, phone calls were monitored by the government, independent organizations not aligned with the Communists were deemed illegal and members were arrested, access to roads was restricted, the borders were sealed, ordinary industries were placed under military management, and workers who failed to follow orders faced the threat of a military court.

Solidarity was the most famous of various organizations which were criminalized, and its members faced the possibility of losing their jobs and imprisonment. However, the heavy-handed repression and resulting economic disaster greatly weakened the role of the Communist Party. Solidarity was eventually legalized again, and shortly thereafter led the country to its first free elections in 1989, in which the communist government was finally removed from power. This inspired a succession of peaceful anti-communist revolutions throughout the Warsaw Pact bloc.

Contemporary Poland (Third Republic of Poland)

Nowadays, Poland is a democratic country with a stable and robust economy. It has been a member of NATO since 1999 and the European Union since 2004. The country's stability has been underscored by the fact that the tragic deaths of the President and a large number of political, business and civic leaders in a plane crash did not have an appreciable negative effect on the Polish currency or economic prospects. Poland has also joined the borderless Europe agreement (Schengen), with an open border to Germany, Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and is on track to adopt the Euro currency in a few years time. Poland's dream of rejoining Europe as an independent nation at peace and in mutual respect with its neighbors has finally been achieved. However rural Poland and the smaller towns have been in decline since the 1990s due to migrants leaving the countryside looking for better jobs in the main cities like Warsaw or Krakow.

Holidays

On public holidays, which including many Catholic holidays and important anniversaries, most service and retail outlets, other companies, museums, galleries, other attractions and public administration units, close entirely. Plan ahead for shopping, services or official business.

On public holidays, which including many Catholic holidays and important anniversaries, most service and retail outlets, other companies, museums, galleries, other attractions and public administration units, close entirely. Plan ahead for shopping, services or official business.

Places to eat, gas stations and pharmacies generally remain open. Some small and almost all Żabka neighbourhood convenience stores stay open, but many may have shortened opening hours. In smaller towns and villages, the local gas station can be your only resort.

Most means of public transport will run according to their Sunday schedule on public holidays, usually meaning less frequent operations. Some connections, e.g. peak bus lines, do not operate on such days entirely ("Sunday service").

If a public holiday falls on a Tuesday or Thursday, many Poles take a day off on the Monday preceding or Friday following to have a long weekend, so many companies and public administration units close on those days as well. Roads and trains may become congested on the days long weekends start or end. In tourist destinations, prices may rise and accommodation may be booked out long in advance. On the other hand, large cities often become relatively deserted.

Catholic religious holidays are widely celebrated in Poland and many provide colourful and interesting festivities and include local traditions. Most of the population, especially in smaller towns and villages, will go to church on those days and participate in them. For Christmas and Easter, it is customary to join one's family for celebratory meals and gatherings that often bring together family members from far away, so many Poles will travel to their home towns or families out of their place of residence. Having celebratory dinners in restaurants is very rare, although many hotels and restaurants would offer Christmas and Easter meals.

- New Year's Day (Nowy Rok) - 1 January is a public holiday, with celebrations taking place around midnight.

- Epiphany (Święto Trzech Króli or Objawienie Pańskie) - 6 January - is the first day of the carnival period. In many Polish cities, merry parades are organised to commemorate the biblical Wise Men.

- Easter (Wielkanoc or Niedziela Wielkanocna) is scheduled according to the moon calendar, usually in March or April. Like Christmas, it is primarily a meaningful Christian holiday. On the Saturday before Easter, churches offer special services in anticipation of the holiday, including blessing of food; children bring baskets of painted eggs and candy to be blessed. On Easter Sunday, practicing Catholics go to the morning mass, followed by a celebratory breakfast made of foods blessed the day before. On Easter Sunday, shops, malls, and restaurants are commonly closed.

- Lany Poniedziałek, or Śmigus Dyngus, is a public holiday on the Monday after Easter, and also a holiday. It's the day of an old tradition with pagan roots: groups of kids and teens wander around, looking to soak each other with water. Often groups of boys will try to catch groups of girls, and vice versa; but innocent passers-by are not exempt from the game, and are expected to play along. Water guns and water balloons are common, but children, especially outdoors and in the countryside, use buckets and have no mercy on passers-by. (Drivers - this means keep your windows wound up or you're likely to get soaked.)

- Labour Day (Święto Pracy) - 1 May is a public holiday as well. Politically inspired parades and rallies are often organized, especially in larger cities, and it is best to avoid them as opposing political factions often collide and police will usually close off the area where parades and rallies are held. Combined with May 3 (see below), this holiday provides for a surefire long weekend in most years and will see many Poles enjoy a holiday outside of their hometowns.

- Constitution Day (Święto Konstytucji Trzeciego Maja) - 3 May, celebrated in remembrance of the Constitution of 3 May 1791. The document was a highly progressive attempt at political reform, and it was Europe's first constitution (and world's second, after the US). Following the partitions, the original constitution became a highly poignant symbol of national identity and ideals.

- Pentecost (Zesłanie Ducha Świętego or Zielone Świątki) - movable feast, celebrated 7 weeks after Easter, which is always on a Sunday. It is a relatively low-key religious holiday. Since this is a Sunday, it may make little difference in some cases, but in case of establishments normally open on Sundays you may find them closed on that day. The second day (Monday) is not a public holiday and not widely celebrated in Poland.

- The Feast of Corpus Christi (Boże Ciało) is celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday, or sixty days after Easter. It is celebrated across the country; in smaller locations virtually the whole village or town becomes involved in a procession, and all traffic is stopped as the procession weaves its way through the streets.

- Assumption (Wniebowzięcie Najświętszej Marii Panny) coinciding with Day of the Polish Military (Święto Wojska Polskiego) - 15 August, commemorating the victory of the Polish Army over the invading Soviet (Red) Army in the Battle of Warsaw. The victory was attributed by the religious to the influence of the Virgin Mary. The day is marked with Catholic religious festivities and military parades.

- All Saints Day (Wszystkich Świętych) - 1 November. In the afternoon people visit graves of their relatives and light candles. After dusk cemeteries glow with thousands of lights and offer a very picturesque scene. If you have the chance, visit a cemetery to witness the holiday. Many restaurants, bars and cafés will either be closed or close earlier than usual on this holiday.

- Independence Day (Narodowe Święto Niepodległości) - 11 November, celebrated to commemorate Poland's independence in 1918, after 123 years of partitions and occupation by Austria, Prussia and Russia. Some somber official celebrations, and another slew of politically-inspired rallies are bound to be held. There are also big patriotic demonstrations and marches in larger cities, especially in Warsaw, where over 100,000 people participate in the salt marsh soil of the Independence. It is calm and many foreigners participate in it.

- Christmas Eve (Wigilia Bożego Narodzenia or simply Wigilia) - 24 December is not a public holiday, but for the Poles it is the year's most important feast. According to Catholic tradition, celebration of liturgical feasts starts in the evening of the preceding day (a vigil, hence wigilia). In Polish folklore, this translates into a special family dinner, which traditionally calls for a twelve-course meatless meal (representing the twelve apostles), which is supposed to begin in the evening, after the first star can be spotted in the night sky. On Christmas Eve most stores will close around 14:00 or 15:00 at the latest out of respect for traditions. It is also a Polish tradition to not leave anybody alone on Christmas Eve, so Polish people tend to be extremely hospitable on the evening and on many occasions will invite their lonely friends to participate in the traditional dinner. It is also acceptable to ask your friends if you could join them if you're alone. There's also a tradition of Midnight Mass on that day (Pasterka), when Christmas carols are sung.

- Christmas (Boże Narodzenie) - 25 and 26 December. On Christmas Day people usually stay home and enjoy meals and meetings with families and sometimes close friends. Everything apart from essential services will be closed and public transport will be severely limited.

- New Year's Eve (Sylwester) - 31 December is not a public holiday, but many businesses will close early. Pretty much all hotels, restaurants, bars and clubs will host special balls or parties, requiring previous reservations and carrying hefty price tags. In cities, free open-air parties with live music and firework displays are organized by the authorities on central squares.

Talk

See also: Polish phrasebook

The official language of Poland is Polish.

Virtually all official information is in Polish only, including street signs, directions, information signs, etc., as well as schedules and announcements at train and bus stations. Airports and a few major train stations usually do have information in English, though. Information signs in museums, churches, etc., signs are typically in multiple languages at popular tourist destinations, elsewhere in Polish only.

The vast majority of young people who grew up after the fall of communism know English, usually at a decent level. Older Poles, however, especially those outside the main cities, will speak little or no English. However, it is possible that they speak either French, German or Russian, taught in schools as the main foreign languages until the 1990s. German remains very common, especially in Western Poland and tourist hotspots like Krakow and Gdansk. However, speaking Russian to Poles remains a sensitive issue due to over a century of unwanted Russian and Soviet domination, so be sure to begin the conversation in Polish and ask if the person speaks Russian before proceeding, and only use Russian as a last resort.

Czech and Slovak are West Slavic languages that share many similarities with Polish; it can be possible to hold an actually decent conversation in those languages. People who speak Ukrainian and Belarusian might be able to get the gist of what is being said in Polish, but holding anything more than a basic conversation will be tedious.

A few phrases go a long way in Poland. Polish people generally love the few foreigners who learn Polish or at least try to. Younger Poles will also jump at the chance to practise their English.

Do your homework and try to learn how to pronounce the names of places. Polish has a very regular pronunciation, and although there are a few sounds unknown to most English speakers, mastering every phoneme is not required to achieve intelligibility; catching the spirit is more important.

There are Polish language schools in Łódź, Kraków, Wrocław, Sopot and Warsaw.

Get in

Entry requirements

Poland is a member of the Schengen Agreement.

- There are normally no border controls between countries that have signed and implemented the treaty. This includes most of the European Union and a few other countries.

- There are usually identity checks before boarding international flights or boats. Sometimes there are temporary border controls at land borders.

- A visa granted for any Schengen member is valid in all other countries that have signed and implemented the treaty.

- Please see Travelling around the Schengen Area for more information on how the scheme works, which countries are members and what the requirements are for your nationality.

In addition to the ordinary Schengen visa waiver, citizens of South Korea, the United States of America, and Israel are permitted to spend up to 90 days in Poland without a visa, regardless of time spent in other Schengen countries. Time spent in Poland, however, does count against the time that would be granted by another Schengen state.

Regular visas are issued for travelers going to Poland for tourism and business purposes. Regular visas allow for one or multiple entries into Polish territory and stay in Poland for maximum up to 90 days and are issued for the definite period of stay. When applying for a visa, please indicate the number of days you plan to spend in Poland and a date of intended arrival. Holders of regular visas are not authorized to work.

Ukrainian citizens do not require a separate visa for transit through Poland if they hold a Schengen or a UK visa.

By plane

Most of Europe's major airlines fly to and from Poland. Poland's flag carrier is LOT Polish Airlines, a member of Star Alliance, operating the Miles&More frequent flyer programme with several other European Star Alliance members. Most other European legacy carriers maintain at least one connection to Poland, and there are also a number of low cost airlines that fly to Poland including WizzAir, EasyJet, Norwegian and Ryanair.

.jpg/440px-LOT_-_Polish_Airlines_-_Polskie_Linie_Lotnicze_Boeing_787-8_Dreamliner_-_SP-LRE_-_Flight_LOT45_from_WAW_(14084309468).jpg) While there are many international airports across Poland, and international air travel is on a constant increase, Warsaw's Chopin Airport (IATA: WAW) remains the country's main international hub. It is the only airport offering direct intercontinental flights - LOT flies to Beijing, Delhi, Toronto, New York and Chicago, while Qatar Airways and Emirates offer flights to their hubs in the Middle East, which allows connecting to their rich international networks. Most European airlines offer a connection to Warsaw, allowing you to take advantage of connecting flights via their hubs.

While there are many international airports across Poland, and international air travel is on a constant increase, Warsaw's Chopin Airport (IATA: WAW) remains the country's main international hub. It is the only airport offering direct intercontinental flights - LOT flies to Beijing, Delhi, Toronto, New York and Chicago, while Qatar Airways and Emirates offer flights to their hubs in the Middle East, which allows connecting to their rich international networks. Most European airlines offer a connection to Warsaw, allowing you to take advantage of connecting flights via their hubs.

Warsaw is the only city in Poland that has two international airports - Modlin Airport (IATA: WMI), a converted former military airfield, is close to Warsaw and normally used by low-fare carriers.

Other major airports serviced by airlines providing intercontinental connections include:

- Kraków (IATA: KRK) - via Vienna, Rome, Moscow, Berlin, Helsinki, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Munich and Warsaw

- Katowice (IATA: KTW) - via Munich, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Warsaw

- Gdańsk (IATA: GDN) - via Berlin, Frankfurt, Copenhagen, Oslo and Warsaw

- Poznań (IATA: POZ) - via Munich, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Copenhagen and Warsaw

- Wrocław (IATA: WRO) - via Frankfurt, Munich, Düsseldorf, Copenhagen and Warsaw

- Rzeszów (IATA: RZE) - via Frankfurt and Warsaw

- Łódź (IATA: LCJ) - via Copenhagen (due to proximity to Warsaw Chopin Airport, there are no flights to Warsaw from Łódź)

Smaller regional airports offering international flights include:

- Bydgoszcz (IATA: BZG) (Great Britain and Ireland with Ryanair; Lufthansa started a Frankfurt route in March 2015 with 4 flights a week)

- Szczecin (IATA: SZZ) (intercontinental connections via Warsaw)

- Lublin (IATA: LUZ) opened in late 2012, serviced by Wizz Air and Ryanair

All of the above airports are also served by low-fare point-to-point carriers, flying to European destinations. The most popular connections out of Poland's regional airports are to the UK, Ireland, Sweden and Norway, where sizeable Polish minorities generate sustainable demand for air traffic. Flights are thus frequent and one can purchase a ticket at a very favorable rate.

By train

- Berlin - Frankfurt (Oder) - Rzepin - Swiebodzin - Zbaszynek - Poznań - Konin - Kutno - Warsaw, 4 a day, 6 hr.

- Berlin - Frankfurt (Oder) - Rzepin - Swiebodzin - Zbaszynek - Poznań - Gniezno - Inowroclaw - Bydgoszcz - Tczew - Gdansk - Gdynia, one a day, 6 hr.

- Berlin - Frankfurt (Oder) - Rzepin - Zielona Gora - Glogow - Lubin - Legnica - Wrocław - Opole - Gliwice - Zabrze - Katowice - Kraków, one daytime and one overnight, 7 hr 30 min.

- Berlin - Szczecin has two direct services, 2 hr, but usually you change between local trains at Angermünde.

- Budapest - Vac - Visegrad - Szob - Bratislava - Breclav - Ostrava - Bohumin - Chalupki - Wodislaw - Rybnik - Katowice - Sosnowiec - Dabrowa Gornicza - Zawiercie - Wloszczowa Polnoc - Opoczno Poludnie - Warsaw, one daytime train (10 hr) which continues to Terespol (for Belarus), and one overnight (14 hr) terminating in Warsaw. At Katowice a portion of the daytime train splits for Kraków and Przemyśl (for Ukraine).

- Vienna - Breclav then the same route via Ostrava and Katowice to Warsaw, 7 hr 40 min, one daytime train continuing to Gdansk and Gdynia, and one overnight terminating in Warsaw. There are other connections via Kraków.

- Prague - Pardubice - Olomouc - Ostrava - Bohumin - Chalupki - Wodislaw - Rybnik - Katowice - Myslowice - Jaworzno Szczakowa - Kraków - Miechow - Wloszczowa Polnoc - Opoczno Poludnie - Warsaw, one daytime (8 hr 30 min) and one overnight (11 hr).

- From Paris or Amsterdam travel via Berlin.

The countries to the east all use the broader (Russian-style) gauge, so there is a change of trains and border formalities to factor into the timetable. A western gauge Rail Baltica is being built through the Baltic states and might, just might, be completed some time in the 21st century.

- Vilnius - Kaunas - Białystok - Warsaw - Krakow trains run daily: you change at the border but it's a seamless connection.

- Kyiv - Dorohusk - Chelm - Rejowiec - Trawniki - Swidnik - Lublin - Naleczow - Pulawy Miasto - Deblin - Pilawa - Warsaw, 16 hr overnight, with daytime connections via Lviv and Przemyśl.

- Trains from Kaliningrad, Moscow, Smolensk and Minsk no longer cross into Poland.

Stations in Poland are relatively small and easy to navigate, though signage is just in Polish. Write down your destination and preferred time to show to ticket clerks, as trains have different prices, and your attempts to pronounce "Wrocław" will likely get you sent to Rouen. They'll show you the price on their calculator or till display, easier to grasp than their reply of trzydzieścipięćzłotychczterdzieściproszę! Credit cards are usually acceptable. See individual cities for which station to use: "Główny" means main station, but in Warsaw you want Centralna.

By car

You can enter Poland by one of many roads linking Poland with the neighboring countries. Since Poland's entry to the Schengen Zone, checkpoints on border crossings with other EU countries have been removed.

However, the queues on the borders with Poland's non-EU neighbors, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, are still large and in areas congested with truck traffic it can take up to several hours to pass.

By bus

See also: Intercity buses in Europe

The principal long-distance bus operator to Poland is Flixbus. As of 2021, their direct international routes are:

- from Berlin via BER airport and Poznań, four daily, 8 hr.

- from Munich via Nuremberg, Bayreuth, Chemnitz, Dresden and Wrocław, daily, 17 hr.

- from Tallinn via Riga, Kaunas, Suwałki and Augustów, daily, 17 hr.

Flixbus and similar big operators are franchises, with real buses with real drivers run by subsidiary local firms. Others are Eurolines, Ecolines and Sindbad.

By boat

See also: Ferries on the Baltic Sea

- From Sweden: Ystad (7–9 hours, 215 zł) by Unity Line; Karlskrona (10 hours, 140-220 zł) by Stena Line; Nynäshamn (18 hours, 230-270 zł), Visby (13½ hours, 170 zł), Ystad (9½ hours, 230 zł) by Polferries

- From Germany: Rostock (~15 hr) by Finnlines

- With your own boat: many Baltic estuaries have marinas, with the largest in Szczecin, Łeba, Hel, Gdynia and Gdańsk. Gdańsk has two yacht docks: one next to the old market square (), which is usually quickly overloaded, and one in the national sailing center next to the city center, close to the Baltic sea. The newest yacht dock is on the longest wooden pier in Sopot. Although there are many sailors in Poland, marine infrastructure still needs to be improved.

Get around

Polish road infrastructure is extensive but generally poorly maintained, and high speed motorways in place are insufficient. However, public transport is quite plentiful and inexpensive: buses and trams in cities, and charter buses and trains for long-distance travel.

.jpg/440px-Boarding_(2564643532).jpg)

By plane

LOT Polish Airlines offers domestic flights between Warsaw Chopin Airport and the airports of Kraków, Katowice, Wrocław, Poznań, Szczecin, Gdańsk, Olsztyn (only in summer season), Zielona Góra, Rzeszów and on the route between Kraków and Gdańsk. The best prices are available in booking 60 days in advance. Prices are 60-130 zł. Ryanair offers daily flights from Warsaw Chopin to Gdańsk, Wrocław and Szczecin and on route between Kraków and Gdańsk. Prices start from 9 zł. Connections from Radom to Wrocław and Gdańsk are operated by Sprint Air. There are no domestic flights to or from Warsaw Modlin, Łódź, Bydgoszcz and Lublin airports.

Every Wednesday, LOT holds a 24 hours ticket sale for return flights originating at Warsaw airport and often some other Polish airports, also including some domestic connections. The discounted flights offered are usually a few months away from the date of sale, and the number of tickets and available dates is restricted, but if you are planning ahead on visiting Poland or other European countries, you may find this offer attractive.

By train

Inter-city routes are operated by PKP (Polskie Koleje Państwowe). Local routes are operated by Polregio, the brand name of Przewozy Regionalne, hived off from PKP in 2008 and now owned by the local city or regional governments. The principal rail corridors lie on international routes as described in Get in:

- From Germany to Poznań - Konin - Kutno - Warsaw - Terespol and Białystok (for Lithuania and Belarus).

- Gdynia - Gdansk - Bydgoszcz - Inowroclaw - Poznań - Wrocław - Katowice (for Czech Republic) - Kraków.

- Gdynia - Gdansk - Warsaw - Kraków.

- Kraków - Tarnów - Rzeszów - Przemyśl (for Ukraine).

For example Warsaw-Kraków (every two hours) and Warsaw-Gdansk (hourly) both take under 3 hours.

Tickets are cheap by west European standards. A day-trip between Warsaw and Kraków, three hours each way, in 2021 might be 100 złoty or €22. This means limited scope for discounts, but see below.

Inter-city trains are modern, comfy and fairly punctual. On local lines there are still a few gnarly O-class trains that look like escapees from a heritage tramway, with old codgers in flat caps sitting on bench seats around the brake handle.

Train types

- EIP (Express Intercity Premium), EIC (ExpressInterCity), EC (EuroCity), and IC (Intercity) - express trains between metro areas, and to major tourist destinations. Reservations are usually required. Power points for laptops are sometimes provided next to the seat. Company: PKP Intercity.

- TLK (Twoje Linie Kolejowe) - discount trains, slower but cheaper than the above. Not many routes, but a very good alternative for budget travelers. Reservations are mandatory for 1st and 2nd class. It uses older carriages that are not always suited to high-speed travel. There are also several night trains connecting southern Poland with the north. Company: PKP Intercity.

- RE (RegioEkspress) - cheaper than TLK and of an even higher standard, but only 3 of these type are running: Lublin - Poznań, Warsaw - Szczecin and Wrocław - Dresden. Company: Przewozy Regionalne.

- IR (InterRegio) - cheaper than TLK and RegioExpress but most routes are supported by poor quality trains. Company: Przewozy Regionalne.

- REGIO/Osobowy - ordinary passenger train; usually slow, stops everywhere. You can also buy a weekend turystyczny ticket, or a week-long pass. Great if you are not in a hurry, but expect these to be very crowded at times. Company: Przewozy Regionalne; other.

- Podmiejski - suburban commuter train. Varying degrees of comfort and facilities. Tickets need to be bought at station ticket counters. Some companies allow you to buy a ticket on board from the train manager, in the very first compartment. A surcharge will apply.

- Narrow gauge - Poland still retains a number of local narrow-gauged railways. Some of them are oriented towards tourism and operate only in summer or on weekends, while others remain active as everyday municipal rail. See Polish narrow gauge railways.

Tickets

It's probably easiest to buy InterCity tickets on-line (see links below). You can also buy tickets on-line for Regio, RE, IR and TLK.

Tickets for any route can generally be purchased at any station. For a foreigner buying tickets, this can prove to be a frustrating experience, since only cashiers at international ticket offices (in major cities) can be expected to speak multiple languages. It is recommended that you buy your train tickets at a travel agency or on-line to avoid communication difficulties and long queues.

It may be easier to buy in advance during peak seasons (e.g. end of holiday period, New Year) for trains that require reserved seating.

Tickets bought for E-IC, EC, EXpress, etc. trains are not valid for local/regional trains on the same routes. If you change trains between InterCity and Regional you have to buy a second ticket.

- Timetable search (in English, but station names of course in Polish)

- PKP information: +48 22 9436, international information +48 22 5116003.

- PKP Intercity serves express connections (tickets can be bought on-line and printed or shown to the conductor on a smart-phone, laptop or similar devices)

- Przewozy Regionalne tickets (dead link: January 2023) for Regio, RE and IR - only Polish version; you should provide yourself a ticket printout.

- Polrail Service offers a guide to rail travel in Poland and on-line purchase of tickets and rail passes for Polish and international trains to neighbouring countries. There's a fee of around 22 zł for every ticket.

- PolishTrains allows to search, book and buy train tickets to numerous Polish and European destinations. Comparison of many train carriers allows to choose the best travel solution and purchase ticket online in the best price.

- Traffic info about all moving trains - check, if the train has a delay

If you travel in a group with the Regional, you should get a 33% discount for the 2nd, 3rd and 4th person (offer Ty i 1,2,3).

If you are a weekend traveller think about the weekend offers, which are valid from Friday 19:00 until Monday 06:00:

- for all Intercity trains (E-IC, Ex, TLK) Bilet Weekendowy (from 154 zł, reservation not included)

- for TLK Bilet Podróżnika (74zł) + Regio Bilet Plus (from 17 zł)

- for all Regional trains (REGIO, IR, RE) Bilet Turystyczny (from 79 zł)

- only for Regio trains Bilet Turystyczny (from 45 zł) If a weekend is extended for some national holiday, the ticket will also extend.

Travellers under 26 years of age and studying in Poland are entitled to 26% discount on travel fare on Intercity's TLK, EX and IC-category trains, excluding the price of seat reservation.

An early booking (7 days before departure) nay be rewarded with additional discounts. (dead link: January 2023)

For some IC trains you can travel with the offer Bilet Rewelacyjny - you will get an automatic discount (ca 20%) on chosen routes (dead link: January 2023).

By bus

Poland has a very well developed network of private charter bus companies, which tend to be cheaper, faster, and more comfortable than travel by rail. For trips under 100 km, charter buses are far more popular than trains. However, they are more difficult to use for foreigners, because of the language barrier.

There is an on-line timetable available. It available in English and includes bus and train options so you can compare: e-podroznik.pl. Online timetables are useful for planning, however, there are multiple carriers at each bus station and departure times for major cities and popular destinations are typically no longer than thirty minutes in-between.

Each city and town has a central bus station (formerly known as PKS), where the various bus routes pick up passengers; you can find their schedules there. Bus routes can also be recognized by signs on the front of the bus that typically state the terminating stop. This is easier if picking up a bus from a roadside stop, rather than the central depot. Tickets are usually purchased directly from the driver, but sometimes it's also possible to buy them at the station. If purchasing from the driver, simply board the bus, tell the driver your destination and he will inform you of the price. Drivers rarely speak English, so often he will print a receipt showing the amount.

Buses are also a viable choice for long-distance and international travel; however, long-distance schedules are usually more limited than for trains.

Flixbus (ex-PolskiBus) takes a more 'western' approach - you can only buy tickets through the Internet and the prices vary depending on the number of seats already sold. They have bus links between Warsaw and most of the bigger Polish cities (as well as a few neighbouring capitals).

By car

See also: Driving in Poland

While the road network in Poland still lags behind many of its western neighbours, in particular Germany, there has been continued significant improvement since the 2010s with the opening of many new motorway segments and refurbishments of some long-neglected thoroughfares that were used far above capacity. There are, however, still quite a lot of roads that are not up to snuff for the traffic they are supposed to carry.

Travelling east–west is now generally much easier than a decade prior, with Poznań, Łódź and Warsaw connected to Polish-German border (direction Berlin) with the A2 (E30), and the southern major metropoles – Wrocław, Katowice, Kraków and Rzeszów – connected to Polish-German border (direction Dresden) and Polish-Ukrainian border (direction Lviv) by the A4 (E40).

The main north–south routes A1, S3, S5, as well as the Warsaw–Rzeszów connection by the combination of S17 and S19, are opened to traffic on their primary sections as of 2022. However, S7 (linking Gdańsk, Warsaw, Kraków and the Polish-Slovak border) is notably not completed despite carrying high traffic volumes, and one needs to expect large traffic jams near Warsaw and Kraków if driving it during the rush hours or bank holidays. Some major roads, most notably DK1 Tychy–Bielsko Biała (part of the Silesia–Slovakia connection) and parts of DK7 north of Warsaw, south of Warsaw and south of Kraków are non-motorway-standard dual carriageways with at-grade intersections and pedestrian crossings.

Most large and medium-sized cities have ring roads allowing you to bypass them, as do some of the smaller towns that are by the major roads. Some of the city bypasses are already past their capacity and large traffic jams form on them when the traffic in the city reaches high volumes. Most notably, in the rush hours one needs to expect large delays on A4 near Kraków and Wrocław, S6/S7 near Gdańsk and S8 near Warsaw.

By taxi

Use only those that are associated in a "corporation" (look for phone number and a logo on the side and on the top). There are no British style minicabs in Poland. Unaffiliated drivers are likely to cheat and charge you much more. Like everywhere, be especially wary of these taxis near international airports and train stations. They are called the "taxi mafia".

Because of travelers' advice like this (and word of mouth), taxis with fake phone numbers can be seen on the streets, although this seems to have decreased - possibly the police have taken notice. Fake phone numbers are easily detected by locals and cater for the unsuspecting traveler. The best advice is to ask your Polish friends or your hotel concierge for the number of the taxi company they use and call them 10–15 minutes in advance (there's no additional cost). That's why locals will only hail taxis on the street in an emergency.

You can also find phone numbers for taxis in any city on the Internet, on municipal and newspaper websites. Some taxi companies, particularly in larger towns provide for a cab to be ordered on-line or with a text message. There are also stands, where you can call for their particular taxi for free, often found at train stations.

If you negotiate the fare with the driver you risk ending up paying more than you should. Better make sure that the driver turns the meter on and sets it to the appropriate fare (taryfa):

- Taryfa 1: Daytime within city limits

- Taryfa 2: Nights, Sundays and holidays within city limits

- Taryfa 3: Daytime outside city limits

- Taryfa 4: Nights, Sundays and holidays outside city limits

The prices would vary slightly between the taxi companies and between different cities, and there is a small fixed starting fee added on top of the mileage fare.

When crossing city limits (for example, when traveling to an airport outside the city), the driver should change the tariff at the city limit.

Every taxi driver is obliged to issue a receipt when asked (at the end of the ride). You can inquire driver about a receipt (rachunek or paragon) before you get into cab, and resign if his reaction seems suspicious or if he refuses.

Ride-hailing is available in Poland and the following are the most anticipated providers:

By bicycle

Cycling is a good method to get a good impression of the scenery in Poland. The roads can sometimes be in quite a bad state and there is usually no hard shoulder or bicycle lane. Car drivers are careless but most do not necessarily want to kill cyclists on sight which seems to be the case in some other countries.

Rainwater drainage of both city streets is usually in dreadful condition and in the country it is simply non-existent. This means that puddles are huge and common, plus pot-holes make them doubly hazardous.

Especially in the south you can find some nice places for bicycling; e.g. along the rivers Dunajec (from Zakopane to Szczawnica) or Poprad (Krynica to Stary Sącz) or Lower Silesia (Złotoryja - Swierzawa - Jawor). Specially mapped bike routes are starting to appear and there are specialized guide books available so ask a bicycle club for help and you should be just fine. Away from roads which join major cities and large towns you should be able to find some great riding and staying at agroturystyka (room with board at a farmer's house, for example) can be a great experience.

Bike sharing systems (system roweru miejskiego) exist in all Polish major cities in which there is a growing net of bicycle segregated cycle facilities (bike lanes and bike paths are the most common). It is a self-service system in which you can rent a bike on 24/7 basis from early spring to the end of autumn, with rental fees charged according to local tariffs. First 20 minutes of a rent is usually free of charge. Charge for next 40 minutes is 1-2 zł, then every consecutive hour 3-4 zł. The major system operator in Poland is Nextbike. You should register online to get an account, make pre-payment (usually 10 zł) and then can rent bikes in all cities in which this system exists (including towns in Germany and other Central European countries).

By thumb

Hitchhiking in Poland is (on average) OK. Yes, it's slower than its Western (Germany) and Eastern (Lithuania) neighbors, but your waiting times will be quite acceptable! The best places to be picked up at are the main roads, mostly routes between Gdańsk - Warsaw - Poznań and Kraków.

Use a cardboard sign and write the desired destination city name on it.

Do not try to catch a lift where it is forbidden to stop. Look on the verge of the road and there should be a dashed line painted there, not a solid one.

As in any country, you should be careful, there are several reports of Polish hitchhiking trips gone awry, so take basic precautions and you should be as right as rain.

See

Ever since Poland joined the European Union, international travellers have rapidly rediscovered the country's rich cultural heritage, stunning historic sites and just gorgeous array of landscapes. Whether you're looking for architecture, urban vibes or a taste of the past: Poland's bustling cities and towns offer something for everyone. If you'd rather get away from the crowds and enjoy nature, the country's vast natural areas provide anything from dense forests, high peaks and lush hills to beaches and lake reserves.

Cities

Most of the major cities boast lovely old centres and a range of splendid buildings, some of them World Heritage sites. Many old quarters were heavily damaged or even destroyed in WWII bombings, but were meticulously rebuilt after the war, using the original bricks and ornaments where possible. Although remains of the Soviet Union and even scars of the Second World War are visible in most of them, the Polish cities offer great historic sight seeing while at the same time they have become modern, lively places. The capital, Warsaw, has one of the best old centres and its many sights include the ancient city walls, palaces, churches and squares. You can follow the Royal Route to see some of the best landmarks outside the old centre. The old city of Kraków is considered the country's cultural capital, with another gorgeous historic centre, countless monumental buildings and a few excellent museums. Just 50 km from there is the humbling Auschwitz concentration camp which, due to the horrible events it represents, leaves an impression like no other World Heritage site does. The ancient Wieliczka salt mine is another great daytrip from Kraków.

Most of the major cities boast lovely old centres and a range of splendid buildings, some of them World Heritage sites. Many old quarters were heavily damaged or even destroyed in WWII bombings, but were meticulously rebuilt after the war, using the original bricks and ornaments where possible. Although remains of the Soviet Union and even scars of the Second World War are visible in most of them, the Polish cities offer great historic sight seeing while at the same time they have become modern, lively places. The capital, Warsaw, has one of the best old centres and its many sights include the ancient city walls, palaces, churches and squares. You can follow the Royal Route to see some of the best landmarks outside the old centre. The old city of Kraków is considered the country's cultural capital, with another gorgeous historic centre, countless monumental buildings and a few excellent museums. Just 50 km from there is the humbling Auschwitz concentration camp which, due to the horrible events it represents, leaves an impression like no other World Heritage site does. The ancient Wieliczka salt mine is another great daytrip from Kraków.

Once a Hanseatic League-town, the port city of Gdańsk boasts many impressive buildings from that time. Here too, a walk along the Royal Road gives a great overview of notable sights. Wrocław, the former capital of Silesia, is still less well-known but can definitely compete when it comes to amazing architecture, Centennial Hall being the prime example. Its picturesque location on the river Oder and countless bridges make this huge city a lovely place. The old town of Zamość was planned after Italian theories of the "ideal town" and named "a unique example of a Renaissance town in Central Europe" by UNESCO. The stunning medieval city of Toruń has some great and original Gothic architecture, as it is one of the few Polish cities to have escaped devastation in WWII. Other interesting cities include Poznań and Lublin.

Natural attractions

With 23 national parks and a number of landscape parks spread all over the country, natural attractions are never too far away. Białowieża National Park, on the Belarus border, is a World Heritage site for it comprises the last remains of the primeval forest that once covered most of Europe. It's the only place where European Bisons still live in the wild. If you're fit and up for adventure, take the dangerous Eagle's Path (Orla Perć) in the Tatra Mountains, where you'll also find Poland's highest peak. Pieniński National Park boasts the stunning Dunajec River Gorge and Karkonoski National Park is home to some fabulous water falls. The mountainous Bieszczady National Park has great hiking opportunities and lots of wild life. Wielkopolski National Park is, in contrast, very flat and covers a good part of the pretty Poznań Lakeland. The Masurian Landscape Park, in the Masurian Lake District with its 2000 lakes, is at least as beautiful. Bory Tucholskie National Park has the largest woodland in the country and has a bunch of lakes too, making it great for bird watching. The two national parks on Poland's coast are also quite popular: Wolin National Park is on an island in the north-west, Słowiński National Park holds some of the largest sand dunes in Europe.

With 23 national parks and a number of landscape parks spread all over the country, natural attractions are never too far away. Białowieża National Park, on the Belarus border, is a World Heritage site for it comprises the last remains of the primeval forest that once covered most of Europe. It's the only place where European Bisons still live in the wild. If you're fit and up for adventure, take the dangerous Eagle's Path (Orla Perć) in the Tatra Mountains, where you'll also find Poland's highest peak. Pieniński National Park boasts the stunning Dunajec River Gorge and Karkonoski National Park is home to some fabulous water falls. The mountainous Bieszczady National Park has great hiking opportunities and lots of wild life. Wielkopolski National Park is, in contrast, very flat and covers a good part of the pretty Poznań Lakeland. The Masurian Landscape Park, in the Masurian Lake District with its 2000 lakes, is at least as beautiful. Bory Tucholskie National Park has the largest woodland in the country and has a bunch of lakes too, making it great for bird watching. The two national parks on Poland's coast are also quite popular: Wolin National Park is on an island in the north-west, Słowiński National Park holds some of the largest sand dunes in Europe.

Castles & other rural monuments

The Polish countryside is lovely and at times even gorgeous, with countless historic villages, castles, churches and other monuments. Agrotourism is therefore increasingly popular. If you have a taste for cultural heritage, the south western parts of the country offer some of the best sights, but there's great stuff in other areas too. The impressive Gothic Wawel Castle in Kraków may be one of the finest examples when it comes to Poland's castles, but most of the others are in smaller countryside towns. The large, red brick Malbork castle (in northern Poland) is perhaps the most stunning in the country, built in 1406 and today the world's biggest brick Gothic castle. The castle of Książ in Wałbrzych is one of the best examples in historic Silesia, which also brought forward the now semi-ruined Chojnik castle, on a hill above the town of Sobieszów and within the Karkonoski National Park. After surviving battles and attacks for centuries, it was destroyed by lightning in 1675 and has been a popular tourist attraction since the 18th century. The picturesque Czocha Castle near Lubań originates from 1329. A bit off the beaten track are the ruins of Krzyżtopór castle, in a village near Opatów. The Wooden Churches of Southern Lesser Poland are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage, just like the Churches of Peace in Jawor and Swidnica. The Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa and the beautiful, World Heritage listed Kalwaria Zebrzydowska monastery are famous pilgrimage destinations. The lovely Muskau Park in Łęknica, on the German border, has fabulous English gardens and is a UNESCO listing shared with Germany. Poland also shares a world heritage site with Ukraine; the Wooden tserkvas of the Carpathian region. 8 of 16 of these churches are in southeastern Poland, in the Lubelskie, Podkarpackie and Małopolskie regions.

The Polish countryside is lovely and at times even gorgeous, with countless historic villages, castles, churches and other monuments. Agrotourism is therefore increasingly popular. If you have a taste for cultural heritage, the south western parts of the country offer some of the best sights, but there's great stuff in other areas too. The impressive Gothic Wawel Castle in Kraków may be one of the finest examples when it comes to Poland's castles, but most of the others are in smaller countryside towns. The large, red brick Malbork castle (in northern Poland) is perhaps the most stunning in the country, built in 1406 and today the world's biggest brick Gothic castle. The castle of Książ in Wałbrzych is one of the best examples in historic Silesia, which also brought forward the now semi-ruined Chojnik castle, on a hill above the town of Sobieszów and within the Karkonoski National Park. After surviving battles and attacks for centuries, it was destroyed by lightning in 1675 and has been a popular tourist attraction since the 18th century. The picturesque Czocha Castle near Lubań originates from 1329. A bit off the beaten track are the ruins of Krzyżtopór castle, in a village near Opatów. The Wooden Churches of Southern Lesser Poland are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage, just like the Churches of Peace in Jawor and Swidnica. The Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa and the beautiful, World Heritage listed Kalwaria Zebrzydowska monastery are famous pilgrimage destinations. The lovely Muskau Park in Łęknica, on the German border, has fabulous English gardens and is a UNESCO listing shared with Germany. Poland also shares a world heritage site with Ukraine; the Wooden tserkvas of the Carpathian region. 8 of 16 of these churches are in southeastern Poland, in the Lubelskie, Podkarpackie and Małopolskie regions.

Countryside

The countryside throughout Poland is lovely and relatively unspoiled. Poland has a variety of regions with beautiful landscapes and small-scale organic and traditional farms. Travelers can choose different types of activities such as bird watching, cycling or horseback riding.

Culturally, you can visit or experience many churches, museums, ceramic and traditional basket-making workshops, castle ruins, rural centers and many more. A journey through the Polish countryside gives you a perfect opportunity to enjoy and absorb local knowledge about its landscape and people.

Do

- Travel one of the European Cultural Routes that cross Poland: for example Cisterian Route (dead link: December 2020).

- Watch football: Ekstraklasa is the top tier of soccer in Poland, with 16 teams representing all the major cities. The playing season is July to April with a long winter break. The national team usually play home games at Stadion Narodowy (National Stadium) in Warsaw.

- Cycle racing: the premier event is the Tour de Pologne, held over a week in August.

Learn

Education is taken very seriously in Poland, and the country is home to many of Europe's oldest universities. Poles typically attain excellent results at international competitions around the globe, and the country's educational system is often considered to be one of the best systems in the world.

It is obligatory for every Pole to receive an education until they are 18 years old. At the end of compulsory schooling, all Poles have to sit for the matura, an end of school exam that will determine their futures. Superstitions about the exam are common.

The Jagiellonian University, founded in 1364, is one of the oldest universities in the world.

The University of Warsaw, founded in 1816, is widely regarded as the most prestigious institution of higher education in Poland.

Work

Citizens of the EU, EEA, or Switzerland can work in Poland without having to secure a work permit. Everyone else, however, needs to apply for a work permit.

Although Poland has one of the best-performing economies in the world, finding a job can be challenging. A lot of job-related information is in Polish, and there are so many highly educated people in Poland that it has become a problem for the labour market. Furthermore, salaries are low compared to neighbouring countries and for this reason, many Poles emigrate to other countries in search of better opportunities.

TEFL courses (that's Teaching English as a Foreign Language) are run in many cities across Poland. Even if you don't have a working visa or Polish citizenship, it should be no problem for you to offer private lessons. In general students, private and in classes, are very friendly toward their teachers, inviting them for dinner or drinks, and sometimes acting quite emotional during their last lesson. Post your services on telephone poles and bus stops with an email or phone number, or use Gumtree, Poland's version of Craigslist. Gumtree Polska is useful for finding students, and accommodations.

Ekorki is good if you're looking for longer term teaching gigs. It's more formal than Gumtree, and used by serious employers. It is a little bit like Monster.com in the US.

Buy

Money

The legal tender in Poland is the Polish złoty, pronounced zwoty. It is denoted by the symbol "zł" (ISO code:: PLN). The złoty is divided into 100 groszy (see infobox for details).

In 1995, 10,000 old złoty were replaced by one new złoty. When it joined the EU, Poland committed to adopting the euro, but this is opposed by the current government.

Coins come in denominations of 1 grosz, 2 grosze, 5, 10, 20 and 50 groszy, 1 złoty, 2 złote and 5 złotych. Banknotes come in denominations of 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 złotych.

Converting złoty to dollars, euros and pounds

Your usual currency equaling between 2.90 and 4 złoty, do this to convert: Divide by 10 and multiply by 3. Example: <br> • 40 zł / 10 = 4; 4 * 3 ≈ 12 of your usual currency

When your usual currency equals between 4 and 5.70 złoty, do this to convert: Divide by 10 and multiply by 2. Example: <br> • 50 zł / 10 = 5; 5 * 2 ≈ 10 of your usual currency

And your usual currency being between 5.70 and 8 złoty, do this to convert: Divide by 10 and add the half of it. Example:<br> • 60 zł / 10 = 6; 6 + 3 ≈ 9 of your usual currency

This works well for everyday expenses. For rather high amounts of money, it's better to convert with the exact exchange rate, e.g. with an app.

Exchange

Private currency exchange offices (Polish: kantor) are very common, and offer euro or US dollar exchanges at rates that are usually comparable to commercial banks. Exchanges in tourist hot-spots, such as the train stations or popular tourist destinations, tend to overcharge. Avoid "Interchange" Kantor locations, easily recognized by their orange color; the rates they offer are very bad.

Cash

Polish has two types of plural numbers, which you are likely to encounter when dealing with currency. Here are the noun forms to expect:

- Singular: 1 złoty, 1 grosz

- Nominative plural: 2 - 4 złote, grosze, then 22 - 24, 32 - 34, etc.

- Genitive plural: 5 - 21 złotych, groszy, then 25 - 31, 35 - 41, etc.

Withdrawing money

There is an extensive network of cash machines or ATMs (Polish: bankomat).

The ATMs of Santander do not charge a fee for withdrawing money with a foreign Visa or Mastercard. Decline the currency conversion as there is a big markup fee. Silesa Bank/PlanetCash lets you choose between 9 zł or 11%. Most of the other banks, if not all, charge a fee of about 15-18 zł and/or about 12-14% conversion fee. (updated July 2022)

Acceptance of credit cards

Credit cards can be used to pay almost everywhere in the big cities. Even single bus ride tickets can be paid for by cards in major cities provided the passenger buys them in vending machines at bus stops. The exception would be small businesses and post offices where acceptance is not completely universal. Popular cards include Visa, Visa Electron, MasterCard and Maestro. AmEx and Diners' Club can be used in a few places (notably the big, business-class hotels) but are not popular and you should not rely on them for any payments. In some merchants you will be given an option to have the card bill you in złoty or your home currency directly. In the former, your bank will convert the transaction for you (subject to the foreign exchange charges it sets) whereas in the latter, the rates set are usually worse than what your bank uses; hence choose to be charged in złoty.

Cheques

Cheques were never particularly popular in Poland and they are not used nowadays. Local banks do not issue cheque books to customers and stores do not accept them.

Tipping

When you're paying for drinks or a meal in restaurants or bars and you are handed a receipt, you should give the amount you have to pay and wait for the change. If you give the money and say "thank you" it will be treated as a "keep the change" type of tip. This also goes for taxis. The average tip is around 10-15% of the price. It's polite to leave a tip, but it's not uncommon to ignore this practice.

Don't forget to tip tour guides and drivers too, but only if you are happy with the service they have provided.

Exports

It is illegal to export goods older than 55 years that are of ANY historic value. If you intend to do so you need to obtain a permit from the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.

Shopping

Prices in Poland are among the lowest in Europe.

Hypermarkets are dominated by western chains: Carrefour, Tesco, Auchan, Real. Some are open 24 hours a day, and are usually in shopping malls or suburbs.

However Poles shop very often at local small grocery stores for bread, meat, fresh dairy, vegetables and fruits - goods for which freshness and quality is essential.

Many towns, and larger suburbs, hold traditional weekly town markets, similar to farmers' markets popular in the West. Fresh produce, baker's goods, dairy, meat and meat products are sold, along with everything from flowers and garden plants to Chinese-made clothing and bric-a-brac. In season wild mushrooms and forest fruit can also be bought. Markets are held on Thursdays, Fridays or Saturdays and are a great way to enjoy the local colour. Prices are usually set though you can try a little good-natured bargaining if you buy more than a few items.

Eat

Tipping

For the most part, Polish restaurants and bars do not include gratuity in the total of the check, so your server will be pleased if you leave them a tip along with the payment. On average, you should tip 10% of the total bill. If you tip 15% or 20%, you probably should have received excellent service. Also, saying "Dziękuję" ("thank you") after paying means you do not expect any change back, so watch out if you're paying for a 10 zł coffee with a 100 zł bill. With all that said, many Poles may not leave a tip, unless service was exceptional. Poles don't usually tip bar staff.

Poles take their meals following the standard continental schedule: a light breakfast in the morning (usually some sandwiches with tea/coffee), then a larger lunch (or traditionally a "dinner") at around 13:00-14:00, then a supper at around 19:00.

It is not difficult to avoid meat, with many restaurants offering at least one vegetarian dish. Most major cities have some exclusively vegetarian restaurants, especially near the city centre. Vegan options remain extremely limited, however.

Traditional local food

Traditional Polish cuisine tends to be hearty, rich in meats, sauces, and vegetables; sides of pickled vegetables are a favourite accompaniment. Modern Polish cuisine, however, tends towards greater variety, and focuses on healthy choices. In general, the quality of "store-bought" food is very high, especially in dairy products, baked goods, vegetables and meat products.

Traditional Polish cuisine tends to be hearty, rich in meats, sauces, and vegetables; sides of pickled vegetables are a favourite accompaniment. Modern Polish cuisine, however, tends towards greater variety, and focuses on healthy choices. In general, the quality of "store-bought" food is very high, especially in dairy products, baked goods, vegetables and meat products.

A dinner commonly includes the first course of soup, followed by the main course. Among soups, barszcz czerwony (red beet soup, also known as borscht) is perhaps the most recognizable: a spicy and slightly sour soup, served hot. It's commonly poured over dumplings (barszcz z uszkami or barszcz z pierogami), or served with a fried pâté roll (barszcz z pasztecikiem). Other uncommon soups include zupa ogórkowa, a cucumber soup made of a mix of fresh and pickled cucumbers; zupa grzybowa, typically made with wild mushrooms; also, flaki or flaczki - well-seasoned tripe. The most common in restaurants is the żurek, a sour-rye soup served with traditional Polish sausage and a hard-boiled egg.

A dinner commonly includes the first course of soup, followed by the main course. Among soups, barszcz czerwony (red beet soup, also known as borscht) is perhaps the most recognizable: a spicy and slightly sour soup, served hot. It's commonly poured over dumplings (barszcz z uszkami or barszcz z pierogami), or served with a fried pâté roll (barszcz z pasztecikiem). Other uncommon soups include zupa ogórkowa, a cucumber soup made of a mix of fresh and pickled cucumbers; zupa grzybowa, typically made with wild mushrooms; also, flaki or flaczki - well-seasoned tripe. The most common in restaurants is the żurek, a sour-rye soup served with traditional Polish sausage and a hard-boiled egg.

.jpg/440px-Chlodnik_(Cold_Borscht).jpg) Pierogi are, of course, an immediately recognizable Polish dish. They are often served alongside another dish (for example, with barszcz), rather than as the main course. There are several types of them, stuffed with a mix of cottage cheese and onion, or with meat or even wild forest fruits. Gołąbki are also widely known: they are large cabbage rolls stuffed with a mix of grains and meats, steamed or boiled and served hot with a white sauce or tomato sauce.

Pierogi are, of course, an immediately recognizable Polish dish. They are often served alongside another dish (for example, with barszcz), rather than as the main course. There are several types of them, stuffed with a mix of cottage cheese and onion, or with meat or even wild forest fruits. Gołąbki are also widely known: they are large cabbage rolls stuffed with a mix of grains and meats, steamed or boiled and served hot with a white sauce or tomato sauce.

Bigos is another unique, if less well-known, Polish dish: a "hunter's stew" that includes various meats and vegetables, on a base of pickled cabbage. Bigos tends to be very thick and hearty. Similar ingredients can also be thinned out and served in the form of a cabbage soup, called kapuśniak. Some Austro-Hungarian imports have also become popular over the years, and adopted by the Polish cuisine. These include gulasz, a local version of goulash that's less spicy than the original, and sznycel po wiedeńsku, which is a traditional schnitzel, often served with potatoes and a selection of vegetables.

When it comes to food-on-the-go, foreign imports tend to dominate (such as kebab or pizza stands, and fast-food franchises). An interesting Polish twist is a zapiekanka, which is an open-faced baguette, covered with mushrooms and cheese (or other toppings of choice), and toasted until the cheese melts. Zapiekanki can be found at numerous roadside stands and bars. In some bars placki ziemniaczane (Polish potato pancakes) are also available. Knysza is a Polish version of hamburger, but it's much (much) bigger and it contains beef, variety of vegetables and sauces. Drożdżówka is a popular sweet version of food-on-the-go, which is a sweet yeast bread (sometimes in a form of kolach) or a pie filled with stuffing made of: poppy seed mass; vanilla, chocolate, coconut or advocaat pudding; baked apples; cocoa mass; sweet curd cheese or fruits.

Poland is also known for two unique cheeses, both made by hand in the [Podhale] mountain region in the south. Oscypek is the more famous: a hard, salty cheese, made of unpasteurized sheep milk, and smoked (or not). It goes very well with alcoholic beverages such as beer. The less common is bryndza, a soft cheese, also made with sheep milk (and therefore salty), with a consistency similar to spreadable cheeses. It's usually served on bread, or baked potatoes. Both cheeses are covered by the EU Protected Designation of Origin (like the French Roquefort, or the Italian Parmegiano-Reggiano).

Polish bread is sold in bakeries (piekarnia in Polish) and shops and it's a good idea to ask on what times it can be bought hot (in a bakery). Poles are often very attached to their favourite bread suppliers and don't mind getting up very early in the morning to obtain a fresh loaf. The most common bread (zwykły) is made of rye or rye and wheat flour with sourdough and is best enjoyed very fresh with butter alone or topped with a slice of ham. Many other varieties of breads and bread rolls can be bought and their names and recipes vary depending on a region. Sweet Challah bread (chałka in Polish) is sold in many bakeries.