See also: European history

The Russian Empire (Российская Империя) was the largest contiguous country in modern times, and the predecessor of the Soviet Union and present-day Russia. Reaching its maximum size during the mid-19th century, it included much of east and central Europe (including Finland and Poland), all of Siberia, much of Central Asia, briefly Alaska and even Fort Ross as far south as present-day California, though the degree of actual control by the tsarist authorities usually declined quite notably going from west to east. It also had a few concessions in China. Through world history, only the Mongol Empire and the British Empire have possessed a larger land area than Imperial Russia.

Though two world wars and Soviet iconoclasm destroyed parts of the Russian imperial heritage, there are still many sites and artifacts left to see.

| | | | Russia historical travel topics:<br>Russian Empire → Soviet Union |

Understand

While the Russian Empire was officially proclaimed in 1721, it was preceded by Russian kingdoms dating back as early as the 9th century.

The Rurikids

In the 8th and 9th century Viking explorers and traders started to navigate on the mighty Russian rivers to reach the Arab Muslim and Byzantine Greek Empires around the Mediterranean. When travelling through Russia, the Vikings came into contact – and conflict – with local Slavic tribes. Legend has it that these "...drove the Varangians (Vikings) back beyond the sea, refused to pay them tribute, and set out to govern themselves", only to find themselves deteriorating into fragmentation and strife. To solve their disunity they invited one Viking chieftain, Rurik, back to rule them. Rurik founded the first Russian dynasty in 862, setting up court in Staraya Ladoga but later moving to Novgorod. His successor Oleg of Novgorod expanded the kingdom southward, and moved the capital to Kiev after conquering it, giving the realm its name Kievan Rus. The modern countries of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus all claim their origins in Kievan Rus, and this continues to be a major bone of contention between Russia and Ukraine, with Ukrainians often accusing Russians of appropriating their history.

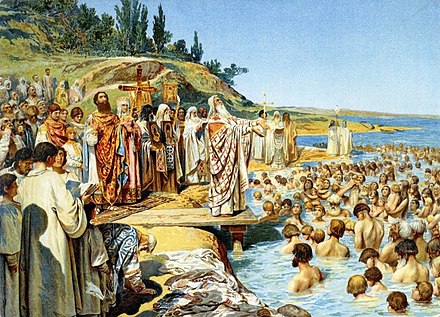

By the end of the first millennium, European paganism was going out of style due to Christianization. To find a new, more modern religion for his realm, Rurik’s great-grandson Vladimir the Great, also known as St. Vladimir of Kiev, invited representatives of all the known major monotheistic religions: Islam, Judaism, and Christianity to plead their case and convince him to adopt their faith. Vladimir was initially attracted to Islam. However, he decided against it when he learned about the Muslim taboo against drinking alcohol and eating pork with the words "Drinking is the joy of all Rus'. We cannot exist without that pleasure." He next considered the Judaic faith. He rejected it however, taking the destruction of Jerusalem and subsequent diaspora as evidence that the Jews had been abandoned by their god. To decide the matter, Vladimir sent his own envoys to investigate the different religions. His emissaries argued that the Muslim Volga Bulgars lacked joy, and found the Catholic Germans much too gloomy. However, of Constantinople's Greek Orthodox cathedral Hagia Sophia, they said "We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth". This decided the matter, and in 988 Vladimir and his court became Orthodox Christians in an event which has later been known as "the Baptism of Rus'". As a consequence, Russia was introduced to the Christian and Byzantine Greek cultural sphere, which has heavily influenced the country since.

During the following century, Rus' prospered from trade with its newfound Byzantine ally. However, in the 12th century, the realm fragmented into a dozen different more or less independent principalities. This made Russia an easy target during the Mongol invasion of the 1220s.

During the next 250 years, the Russian principalities suffered under "the Tatar yoke", becoming tribute-paying vassals of the Khans. The most successful of these princedoms was Moscow, which adopted the role of emissaries and tribute collectors of the Mongols. Using this position, it was able to expand its influence at the expense of the other Russian principalities. By the 1480s, Moscow had grown strong enough to challenge and break free from its Mongol overlords under the leadership of Dmitry Donskoy.

Moscow's main competition for influence in the region was Novgorod, which remained independent due to its position in northwestern Russia, forming a merchant republic similar to that of the German Hanseatic League. In the 13th century the Novgorodian ruler Alexander Nevsky fought German and Swedish invaders, becoming a symbol of Russian independence for centuries to come. In 1478 the Novgorod Republic was conquered by Moscow, which set the stage for Russian absolutism for centuries to come.

In 1453 Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire and centre of Orthodox Christianity, fell into the hands of the Muslim Ottoman Empire. This left Russia the strongest Orthodox country in the world. The Muscovite princes consequently thought of themselves as inheriting the Byzantine Emperors' role as protectors of the true faith, thus proclaiming Moscow as "the third Rome" and its rulers as "Tsars of all Rus'" (The Russian Tsar or Czar and the German Kaiser are derived from Roman Caesar). The Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III "the Great" even married Sophia Palaiologina, niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, to reinforce his claim.

As the absolute ruler of Russia, the first tsar, Ivan IV "the Terrible" (Ива́н Гро́зный Ivan Grozny, lit. Ivan Thunder, fig. the "Fearsome" or Ivan the "Formidable") and his secret police Oprichnina started a reign of terror. In a fit of rage, Ivan even killed his own son and heir. The death of Ivan's other, childless, son Feodor in 1598 marked the end of the 700-year reign of Rurikid dynasty. Without any apparent heir Russia was plunged into chaos, with civil war and foreign invasions, a period later known as "the Time of Troubles". The era ended when the Patriarch of Moscow crowned his own son Mikhail Romanov tsar in 1613.

As the absolute ruler of Russia, the first tsar, Ivan IV "the Terrible" (Ива́н Гро́зный Ivan Grozny, lit. Ivan Thunder, fig. the "Fearsome" or Ivan the "Formidable") and his secret police Oprichnina started a reign of terror. In a fit of rage, Ivan even killed his own son and heir. The death of Ivan's other, childless, son Feodor in 1598 marked the end of the 700-year reign of Rurikid dynasty. Without any apparent heir Russia was plunged into chaos, with civil war and foreign invasions, a period later known as "the Time of Troubles". The era ended when the Patriarch of Moscow crowned his own son Mikhail Romanov tsar in 1613.

The Romanovs

By 1700 Russia was still a peripheral country in European politics. The country was technologically backward and economically underdeveloped. With Archangelsk on the White Sea as its only port, Russia was isolated from western Europe, whose people considered it more barbaric than civilized. The man who was going to change that was the extraordinary tsar Peter I, better known as Peter the Great. The Swedish Empire had expanded eastwards during the 16th and 17th century, nearly encircling the Baltic Sea. As Russia allied with Poland and Denmark in 1699 to contain Sweden, the Great Northern War began. Swedish king Charles XII led a campaign far into the Russian steppes, until he was defeated at Poltava in 1709, allowing Russia to annex the Baltic States. His ambitions did however not stop at the military field. In an effort to modernize his county he launched a program later known as the Petrine Reforms. The reforms ranged from administration to finance to fashion, as he even demanded that the Russian nobles cut their long beards to adopt the Western European hair style. He also more or less reduced the church of Russia to a branch of his own government, to sway any opposition to his reforms. His most awesome achievement was however the construction of a new capital on the freshly conquered mouth of river Neva into the Baltic Sea – Saint Petersburg. The city was constructed according to western European architectural ideas and was intended to become Russia's "Window to the West", a gateway for western European ideas to get into Russia, and for Russia to get into the world. Russia was now established as a great power, and to emphasize his new Western European image Peter rejected the old title "Tsardom of all Rus'", for the more western European name "The Russian Empire", Российская империя.

While the leaders of Russia looked to the west, economic opportunists and adventurers looked to the east. Siberia was a vast land filled with natural resources - most notably prized furs. However, the intense hunt drastically reduced the number of game, motivating the adventurers to move eastward onto greener pastures. And where the hunters and adventurers went, colonists followed. Thus, step by step, Russia conquered and colonized Siberia and the Russian Far East, beginning in the late 16th century and reaching the Pacific Ocean in 1639, decimating most of their native populations in the process. The Danish-born Russian naval commander Vitus Bering claimed Kamchatka for the empire in 1728, and in 1741 reached Alaska but died on the return trip. Alaska would be sold to to the United States in 1867.

_-_detail.jpg/440px-Napoleon_near_Borodino_(Vereshchagin)_-_detail.jpg) Peter's successors continued his politics of military expansion and cultural modernization. Russia also became, and remains, a patron of the arts, especially classical music and art, rivaling other European empires, such as the Austrian Empire and France. Catherine the Great in particular promoted the Russian intelligentsia, a new class of Western European-educated intellectuals. Still, most of the population remained poor and unlanded, and serfdom persisted until 1861. Under Catherine the Great, Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in several wars, resulting in Russian Empire's borders being expanded westwards into Crimea, Belarus, Central Ukraine and Lithuania. The victory over the former in particular cemented Russia's status as one of Europe's great powers.

Peter's successors continued his politics of military expansion and cultural modernization. Russia also became, and remains, a patron of the arts, especially classical music and art, rivaling other European empires, such as the Austrian Empire and France. Catherine the Great in particular promoted the Russian intelligentsia, a new class of Western European-educated intellectuals. Still, most of the population remained poor and unlanded, and serfdom persisted until 1861. Under Catherine the Great, Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in several wars, resulting in Russian Empire's borders being expanded westwards into Crimea, Belarus, Central Ukraine and Lithuania. The victory over the former in particular cemented Russia's status as one of Europe's great powers.

In the early years of the 19th century, Russia became involved in the Napoleonic Wars, which in Russian historiography is known as "The First Great Patriotic War" (followed by the second 130 years later). In 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia, and managed to capture and burn the ancient Russian metropolis of Moscow. However, the French troops were poorly prepared for the Russian winter, and the cold in combination with Russian guerrilla raids completely annihilated Napoleon's Grande Armée. As one of the victorious allies against Napoleon, Russia consolidated its role as a European great power, and in the following peace treaty of Vienna, Russia was granted Finland from Sweden, while Poland was split among Russia, Prussia and Austria-Hungary.

The French revolution of 1789, the Napoleonic wars, and the failed liberal Decembrist revolt of 1825 reminded the Russian rulers that the liberal ideas of west Europe could also be very dangerous for their monarchy. The Russian rulers thus turned to a more reactionary direction, and thereby came into conflict with the enlightenment ideals and much of the intelligentsia. At the same time the intelligentsia itself became divided between the Zapadniki (lit. "westernizers"), and the Slavophiles. The Zapadniki thought that Russia was still uncivilized and medieval compared to western Europe, and argued for further modernization. The Slavophiles, on the other hand, considered the enlightenment ideals of west Europe superficial and materialistic, and rather wanted to cherish Russia's "unique" Orthodox and spiritual heritage. Due to strict government censorship, much of this cultural debate was expressed in literature, contributing to a golden era for Russian literature.

In the wake of the Second Opium War, Russia was able to force Qing China to sign the Treaty of Aigun in 1858, which resulted in all Chinese territory north of the Amur River being ceded to Russia. After the French and British victory over China in 1860, at the Convention of Peking, the Chinese were forced to cede all territory east of the Ussury River to Russia, resulting in direct Chinese access to the Pacific Ocean being cut off in the northeast. Subsequently, Russia also successfully forced the Chinese to grant them several "concessions" — areas in which Russian citizens enjoyed extraterritorial rights, and where Chinese law did not apply. The first of these were in Hankou and Harbin in 1896, Dalian in 1898, and Tianjin in 1900. To this day, the cities of Harbin and Dalian are known for having a high concentration of Russian architecture, with Harbin also known among the Chinese for its Russian food.

In 1861 Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia. However, as most land was still owned by the nobility, and as the serfs were obliged to compensate their previous owners with usury taxes for the little land they were allotted, the reforms left most serfs as wage- or debt-slaves, liberating them more in name than in fact. Disillusioned and disappointed with the reform, many Zapadniki were radicalized into Nihilists, abandoning rational debate for political violence. In response, the regime became increasingly repressive, and many Slavophiles turned to the more imperialist ideology of Pan-Slavism.

Russia had the ambition to acquire an ice-free port on either the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, or the Indian Oceans. It competed with the British Empire in The Great Game, annexing most of Central Asia except Afghanistan, which remained independent as a buffer zone between the two empires. Russian expansion became a concern for its rivals, and in the 1850s Crimean War, an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France and the United Kingdom prevented Russia from dominating the Black Sea. Another setback was the Russo-Japan War in 1904–1905, the first decisive non-Western victory over a Western great power since the Voyages of Columbus. It resulted in the loss of the southern half of Sakhalin island, and the Russian colonial possession in the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan.

The Russian Revolutions and World War I

The defeat at the hands of Japan contributed to the Russian Revolution of 1905, which delegated much of the emperor’s power to the State Duma, a newly founded parliament.

In 1914, Slavic separatists assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, leading to an Austro-Hungarian ultimatum against Serbia. As Russia backed its Serbian "brothers" (Pan-Slavic ideas being common at the time), Germany honored its alliance with Austria, leading to a destructive conflict today known as World War I. Though German troops pushed far into Russian territory, and the Russian people were driven towards famine, the Tsar was too stubborn to stop fighting. Rising dissent led to the February Revolution in 1917, in which the constitutional monarchy was replaced by a short-lived Provisional Government. However it, too, continued to fight in World War I and was in turn overthrown in the October Revolution in the same year, which brought the Bolshevik government, led by Vladimir Lenin, to power and laid the foundation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar and his family would be imprisoned and eventually executed by the Bolsheviks in February 1918. They were subsequently buried in unmarked graves, which were only re-discovered in 1979 and 2007 respectively. Also called the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the Soviet Union became a global superpower within a couple of decades and remained one until its dissolution in 1991.

For history after the fall of the empire, see Soviet Union, World War II in Europe and Cold War Europe. For information on the countries which now occupy the empire's former territory, see Russia, Caucasus, Central Asia, Belarus, Ukraine, Finland, Poland and the Baltic states.

Destinations

While most historical cities are in Central and Northwestern Russia, as well as Ukraine, Russia expanded eastward during the Age of Discovery, with most settlements in Siberia (including the Russian Far East) rather young in comparison to European Russia.

Many old Russian cities have a kremlin (кремль), essentially a castle or fortress, small or large, some better preserved than others. The largest and by far the most famous one is the one in Moscow that is the seat of the modern Russian government, internationally known as the Kremlin, a term that is also a metonym for the Russian (and formerly Soviet) government.

Russia

- Moscow, 55.7500°, 37.6167°. The capital for much of the Imperial history. Still the biggest and most important city in Russia with many historic and modern sights.

- Saint Petersburg, 59.95°, 30.3°. Founded in 1703, and the Russian capital from the early 18th century until the Bolshevik Revolution. Remarkable in that, at the time of its founding, the Russian claim on the land was shaky at best and the land was not much more than a mosquito-infested swamp nobody really cared about. Also, some suburbs, such as Peterhof, Pavlovsk, Gatchina and Pushkin, feature exorbitantly luxurious imperial palaces.

- Novgorod, 58.52203°, 31.275131°. Known since the 9th century, this city was once the capital of Rus' before it was moved to Kiev, and later the seat of the Novgorod Republic. Its kremlin features the "Millenium of Russia" monument, unveiled in 1862, a must-see within this context.

- Kazan, 55.7833°, 49.1667°. Capital of Tatarstan. Contains a kremlin on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

- Petrozavodsk, 61.7833°, 34.3333°. Founded on September 11, 1703 at the behest of Peter the Great, as his iron foundry and cannon factory, the city has grown to be Karelia's capital. On an island nearby, there's an open air museum of Medieval wooden architecture at Kizhi. 2015-07-29

- Pskov, 57.8167°, 28.3333°. A Medieval city with a kremlin and a cathedral.

- Sevastopol, 44.616406°, 33.524574°. Known in Graeco-Roman times as Chersonesus Taurica, it's the place where Vladimir the Great was baptized in 988. This settlement was sacked by the Mongol Horde several times in the 13th and 14th centuries, and finally totally abandoned, only to be refounded in 1783 as the base of the Black Sea Navy of Russia. It was famously besieged in the Crimean War. As of 2021, it maintains the status of most important Russian Navy base on the Black Sea.

- Orenburg, 51.783333°, 55.1°. This fortress city was founded in 1743 at a strategic confluence then on the frontier. It played a major role in Pugachev's Rebellion (1773–1774), and later on served as a base to several military incursions into Central Asia. 2018-11-28

- Pokrovskoye, 57.24506°, 66.793749°. Located on the northern banks of the Tura River, this village has seen the birth of mystic Grigori Rasputin.

- Shlisselburg, 59.944°, 31.033°. Here the Oreshek fortress was built in 1323, and in the same year a peace treaty with Sweden was signed here. 2020-04-18

- Staraya Ladoga, 59.983333°, 32.3°. Believed to be Russia's first capital city. According to the Hypatian Codex, the Varangian leader Rurik arrived at Ladoga in 862 and made it his capital. Rurik later moved the capital to Novgorod, and his successor Oleg of Novgorod then moved it to Kyiv. 2015-07-17

- Golden Ring. A group of Old Towns.

- Archangelsk, 64.533333°, 40.533333°. Russia's main port to the Atlantic until the 20th century.

- Yekaterinburg, 56.8333°, 60.5833°. Where Nikolai II and his family were imprisoned and later executed by the Soviet revolutionaries. A church on the site of the execution was built in 2003. 2015-12-11

- Tobolsk, 58.2°, 68.266667°. Founded in 1586, Siberia's first capital, features the only standing stone kremlin east of the Urals. 2015-07-17

- Tula, 54.2°, 37.616667°. Site of the first modern armament factory in Russia, commissioned by Peter the Great in 1712. Famous for the quality of its weapons, machine tools, samovars, accordions and gingerbread; each of these has its own museum in the city. 2020-04-06

- Vyborg, 60.716667°, 28.76666°. A formerly Swedish harbour, captured by Peter the Great in 1710 and annexed to the Empire after the war's end. There's a nice Swedish island castle as centerpiece. 2020-04-05

- Black Sea resorts. Since frozen white landscapes dominate the rest of their empire for most of the time, the coastline surrounding the Black Sea, as the warmest part of the empire, was much favoured among the royalty. The tsars had taken their abode in Livadia and Massandra Palaces, both near Yalta 📍 in Crimea, during their vacations, while some other members of the nobility opted for Gagra 📍 in Abkhazia to build a summer residence. Inland Abastumani 📍 was another favourite retreat of the dynasty, thanks to its spa and beautiful forests on the Lesser Caucasus. The botanical gardens of Sochi 📍, Sukhumi 📍 and Batumi 📍 further south were all started during the imperial period. 2015-11-11

- Trans-Siberian Railway - running from Moscow to Vladivostok on the Pacific, the world's longest railway uniting Russia and one of the most impressive construction projects in the world. It was finished in 1916, just before the collapse of the Russian Empire.

- Khabarovsk, 48.4833°, 135.0667°. A big and thriving frontier city, by the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri rivers, said to be a big highlight of the Trans-Siberian journey. Home to the well-regarded Far Eastern Museums. 2023-03-29

- Vladivostok, 43.133333°, 131.9°. Originally part of Qing China, and the traditional homeland of the ruling Manchus, the area was annexed by Russia in 1858 under the Treaty of Aigun, and the city was founded on 20 June (2 July) 1860 with the arrival of the transport of the Siberian Military Flotilla Mandzhur under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Alexei Karlovich Shefner. Today, it is the eastern terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, and Russia's main naval base in the Pacific. 2022-09-21

Ukraine

- Kyiv (Kiev), 50.45°, 30.52°. Kyiv's importance in Russian history sparks tensions between Russians and Ukrainians, and is reflected on its huge collection of historic sights, such as St. Sophia cathedral, the Pechersk Lavra monastery (both s), the Kyiv Fortress and the reconstructed Golden Gate.

- [Poltava Battle History Museum](http://www.battle-poltava.org/eng/tours/) (Державний історико-культурний заповідник Поле Полтавської битви), Street Shveds'ka Mohyla (Шведська Могила вул.,), 32 (5 km north-east of city. There are several marshrukta buses going via Zygina Square, as well as buses 4 and 5 right to the bus stop «The museum of the history of Poltava Battle»), 49.6304°, 34.5533°. Su, Tu-Th 09.00-17.00, F 09.00-16.00, M closed. The battlefield where Peter the Great defeated Swedish King Charles XII in 1709, marking the rise of Russia as a European Great Power. There is a museum and a Swedish cemetery. The restricted territory of historical field consists of 1,906 acres. There are 4 old settlements and more than 30 burial mounds (1000 BC and 1000 AD) on the reserve territory.

- Mykolayiv (Nikolayev), 46.966667°, 32°. Main shipbuilding hub for the Russian Empire and later, the Soviet Union. Founded by Prince Grigory Potemkin, a lover of Catherine the Great, he named it Nikolaev after Saint Nicholas of Myra. The city's current English name is the Ukrainian cognate of its Russian name, and was adopted following Ukrainian independence. Today, the city is home to the Museum of Shipbuilding and the Fleet with numerous exhibits dedicated to its shipbuilding history, as well as numerous monuments to that history, including a bust of Grigory Potemkin and the Monument to Shipbuilding. 2022-04-03

Latvia

- Karosta, 56.511667°, 21.013889°. A naval base for the Russian Empire, and later the Soviet Union, it was abandoned following Latvian independence in 1992. Surviving structures from the time of the Russian Empire include St Nicholas Naval Cathedral, the water tower and the ruins of several forts 2021-11-07

Georgia

- Georgian Military Highway, 42.578872°, 44.524727°. Started in its present form by the imperial army during the early expansion of the empire into the Caucasus at the turn of the 19th century, this is an epic journey crossing the Great Caucasus Mountains, considered to be on the boundary between Europe and Asia. However, due to the tense relations between Russia and Georgia, it may not be always possible to complete all of the route end-to-end. 2015-11-11

Turkmenistan

- Kushka (nowadays Serhetabat), 35.283333°, 62.35°. Seized from Afghanistan by the Russian Imperial forces in 1885 (it was then named the Pandjeh Incident, and made world news, one of the last highlights of the so-called Great Game against the British Empire), Kushka was touted in propaganda as the southernmost point of both the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. This is commemorated by a 10-metre stone cross, installed on the tercentenary of the Romanov Dynasty, in 1913. 2016-02-15

Uzbekistan

- Tashkent, 41.3°, 69.266667°. Conquered to the Empire in May 1865, to become the capital of the new territory of Russian Turkistan with General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman as first Governor-General. In 1868 Kaufman campaigned and annexed Bukhara and Samarkand, in 1873 he took Khiva. He is buried at Tashkent Orthodox Cathedral. 2018-11-28

Finland

- Helsinki, 60.171°, 24.938°. Central Helsinki was built while Finland was part of the empire, in a style resembling Saint Petersburg, as the town was made capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Because of its history, Helsinki university has the largest collection of Russian literature and documents from the 19th century outside of Russia. 2016-11-10

Poland

- Warsaw, 52.23°, 21.011111°. Poland lost its sovereignty throughout the course of the 18th century, and was partitioned between Prussia (later Germany), Austria-Hungary and Russia. Warsaw, Poland's modern-day capital was in the Russian partition, and had numerous Russian Orthodox churches built during the period of Russian rule, though most of those churches were demolished when Poland regained its independence in 1918. The two exceptions are the Cathedral of St. Mary Magdalene and St. John Climacus's Orthodox Church, which continue to be Eastern Orthodox churches to this day. 2022-09-18

Turkey

- Kars, 40.606944444444°, 43.093055555556°. Many beautiful rowhouses in this Turkish city date back to its time under the rule of the Russian Empire between 1878 and 1918, when much of the old town was rebuilt on a grid plan. Locally known as the "Baltic style", the Russian architecture in Kars includes a mosque converted from a Russian Orthodox church, less its original pair of cupolas. The pine forests in the outskirts of nearby Sarıkamış 📍 feature a derelict hunting lodge that was built by Tsar Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917), although locals anachronistically named it after Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796). There were also numerous ethnic German villagers scattered over the larger area, tracing their origins to the Volga Germans, but the community died out in 2011 with the death of its last member, and a Lutheran cemetery is the only reminder of their past existence.

China

- Harbin, 45.7576°, 126.6409°. A former Russian concession in Northeast China, with several Russian colonial buildings surviving as a reminder of that era. It is also known for its bitterly cold winters, and today hosts the world-renowned Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival during the coldest part of the winter. Also known among the Chinese for its Russian food, albeit significantly localized.

- Dalian, 38.920833°, 121.639167°. Former Russian concession that is today one of China's major port cities, known in the West as Dalny (Дальний) during that time. Many Russian colonial buildings remain as a reminder of that era, with a particularly high concentration of them on Russian Street, which is now a major tourist attraction. The district of Lüshunkou was known as Port Arthur (Порт-Артур) under Russian colonial rule, and was home to a Russian naval base.

- Tianjin (Tientsin), 39.1336°, 117.2054°. The main port city serving the Chinese capital Beijing today, it was home to a Russian concession, among many others from 1900-1924, when it was returned to China by the successor state of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union. Today, the former Russian concession is still home to the former Russian consulate as a reminder of that era.

- Hankou (Hankow), 30.581179°, 114.272597°. Today part of Wuhan, it was home to numerous foreign concessions in the 19th and early 20th centuries, including a Russian one from 1886-1920. Today, the most visible reminder of Russian colonial rule is the Hankow Orthodox Church, located just at the boundary between the former British and Russian concessions.

United States of America

- Sitka, 57.1°, -135.3°. Established in 1799 by Aleksandr Baranov of the Russian American Company, Sitka became the capital of Russian Alaska. When Russia sold Alaska to the US, the handover ceremony took place on Castle Hill at Sitka, on 18 October 1867.

- Fort Ross, 38.5143°, -123.2427°. A fur trade outpost, established by the Russian-American Company in 1812 and sold to John Sutter in 1841, owing to the depletion of the local population of fur-bearing marine mammals. The subject of intensive archaeological investigation, it's designated a National Historic Landmark.

- Russian Fort Elizabeth, Russian Fort Elizabeth State Historical Park, Kauai. A fort built in the 19th century, along the southwest coast of Kauai. It remains the last Russian fort in Hawaii, as many other Russian forts in Hawaii were dismantled. Today, the fort is pretty much in ruins, though the fort's outer edge can still be seen and visited. 2022-05-07

See also

- Other European colonial empires:

- Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Japanese colonial empire

- Vikings and the Old Norse

- Minority cultures of Russia

- Age of Discovery

- Napoleonic Wars

- World War I

- Soviet Union

- Russian cuisine

- Old West — the eastward expansion of Russia is often compared to the westward expansion of the United States; both involved decimating the indigenous populations and settling the lands with white people who now form the majority