Finland (Finnish: Suomi, Swedish: Finland) is one of the Nordic countries in northern Europe.

The country has comfortable small towns and cities, as well as vast areas of unspoiled nature. The most urbanized infrastructure is mainly concentrated in the southern part of the country and the capital city, Helsinki, located there. About 10% of the area is made up by 188,000 lakes, with a similar number of islands.

Finland extends into the Arctic, where the Northern Lights and the Midnight Sun can be seen. The mythical mountain of Korvatunturi is said to be the home of Santa Claus, and there is a Santaland in Rovaniemi.

While Finland is a high-technology welfare state, Finns love to head to their summer cottages in the warmer months to enjoy all manner of relaxing pastimes including sauna, swimming, fishing and barbecuing during the short but bright summer. Finland has a distinctive language and culture that sets it apart from both Scandinavia and Russia. While Finnish culture is ancient, the country only became independent in 1917, shortly after the collapse of the Russian Empire.

Regions

Southern Finland (Tavastia Proper, Päijänne Tavastia, Uusimaa, Kymenlaakso, South Karelia)

The southern stretch of coastline up to the Russian border, including the capital Helsinki.

West Coast (Central Ostrobothnia, Ostrobothnia, Southern Ostrobothnia, Satakunta, Finland Proper)

The south-western coastal areas, the old capital Turku, and the southern parts of the historical province of Ostrobothnia (Pohjanmaa, Österbotten), with half of Finland's Swedish-speaking population.

Finnish Lakeland (North Savonia, North Karelia, Central Finland, South Savonia, Pirkanmaa)

Forests and lakes from the inland hub city Tampere all the way to the Russian border, including Savonia (Savo) and the Finnish side of Karelia (Karjala).

Northern Finland (Finnish Lapland, Kainuu and Eastern Oulu region, Southern Oulu region, Western Oulu region)

The northern half of Finland is sparsely inhabited, with large mires and deep forests, but also a few important cities like Oulu and Rovaniemi. This is where you find reindeer and fell landscapes, and where you go for winter sports or week-long hikes.

An autonomous, demilitarised and monolingually Swedish group of islands off the south-western coast, where the administration is centered in the port town of Mariehamn.

The current formal divisions of the country do not correspond well to geographical or cultural boundaries, and are not used here. Formerly regions and provinces did correspond; many people identify with their region (maakunta/landskap), but mostly according to historic boundaries. These regions include Tavastia (Häme/Tavastland), covering a large area of central Finland around Tampere, Savonia (Savo/Savolax) in the eastern part of the lakeland Karelia (Karjala/Karelen) to the far east and Ostrobothnia (Pohjanmaa/Österbotten) comprising most of the west coast and some of the northern inland. Much of Finnish Karelia was lost to the Soviet Union in World War II, which still is a sore topic in some circles.

Cities

- Helsinki — the "Daughter of the Baltic", Finland's capital and largest city by far

- Jyväskylä — a university town in Central Finland

- Oulu — a technology city at the end of the Gulf of Bothnia

- Rauma — largest wooden old town in the Nordics and a UNESCO World Heritage site

- Rovaniemi — gateway to Lapland and home of Santa Claus Village

- Savonlinna — a small lakeside town with a big castle and a popular opera festival.

- Tampere — a former industrial city becoming a hipster home of culture, music, art and museums

- Turku — the former capital on the southwest coast. Medieval castle and cathedral.

- Vaasa — a town with strong Swedish influences on the west coast located near the UNESCO world natural site Kvarken Archipelago

Other destinations

- Archipelago Sea - hundreds and hundreds of islands from the mainland all the way to Åland

- Finnish national parks, other protected areas, hiking areas or wilderness areas , e.g.

- Koli National Park – scenic national park in Eastern Finland, symbol for the nature of the country

- Lemmenjoki National Park – gold digging grounds of Lapland, and one of the largest wilderness areas in Europe

- Nuuksio National Park – pint-sized but pretty national park a stone's throw from Helsinki

- Kilpisjärvi - "the Arm of Finland" offers scenic views and the highest hills in Finland

- Levi , Saariselkä and Ylläs – popular winter sports resorts in Lapland

- Suomenlinna – island off the coast of Helsinki where there is a 18–19th century fort that you can visit by ferry <br clear="right" />

Understand

History

Not much is known about Finland's early history, with archaeologists still debating when and where a tribe of Finno-Ugric speakers cropped up. The earliest certain evidence of human settlement is from 8900 BC. Roman historian Tacitus mentions a primitive and savage hunter tribe called Fenni in 100 AD, though there is no unanimity whether this means Finns or Sami. Even the Vikings chose not to settle, fearing the famed shamans of the area, and instead traded and plundered along the coasts.

In the mid-1100s Sweden started out to conquer and Christianise the Finnish pagans in earnest, with Birger Jarl incorporating most of the country into Sweden in 1249. While the population was Finnish-speaking, the Swedish kings installed a Swedish-speaking class of clergy and nobles in Finland, and enforced Western Christianity, succeeding in eliminating local animism and to a large part even Russian Orthodoxy. Farmers and fishermen from Sweden settled along the coast. Finland remained an integral part of Sweden until the 19th century, although there was near-constant warfare with Russia on the eastern border and two brief occupations. Sweden converted to Lutheran Protestantism, which marked the end of the Middle Ages, led to widespread literacy in Finnish and still defines many aspects of Finnish culture. After Sweden's final disastrous defeat in the Finnish War of 1808–1809, Finland became an autonomous grand duchy under Russian rule.

The Finnish nation was built during the Russian time, while the Swedish heritage provided the political framework. The Finnish language, literature, music and arts developed, with active involvement by the (mostly Swedish speaking) educated class. Russian rule alternated between benevolence and repression and there was already a significant independence movement when Russia plunged into war and revolutionary chaos in 1917. Parliament seized the chance (after a few rounds of internal conflicts) and declared independence in December, quickly gaining Soviet assent, but the country promptly plunged into a brief but bitter civil war between the conservative Whites and the socialist Reds, eventually won by the Whites.

During World War II, Finland was attacked by the Soviet Union in the Winter War, but fought them to a standstill that saw the USSR conquer 12% of Finnish territory. Finland then allied with Germany in an attempt to repel the Soviets and regain the lost territory (the Continuation War), was defeated and, as a condition for peace, had to turn against Germany instead (the Lapland War). Thus Finland fought three separate wars during World War II. In the end, Finland lost much of Karelia and Finland's second city Vyborg (Viipuri, Viborg), but the Soviets paid a heavy price with over 300,000 dead. The lost territory was evacuated in a massive operation, in which the former inhabitants, and thus Karelian culture, were redistributed all over the country.

After the war, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union (see Cold War Europe). The Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance committed Finland to resist armed attacks by "Germany or its allies" (read: the West), but also allowed Finland to stay neutral in the Cold War and avoid a Communist government or Warsaw Pact membership. In politics, there was a tendency to avoid any policies and statements that could be interpreted as anti-Soviet. This balancing act of Finlandization was humorously defined as "the art of bowing to the East without mooning the West". Practically, Finland was west of the Iron Curtain and travel to the West was easy. Thus, even many older people know English and German and have friends in the West, while Russian was not compulsory and is even today scarcely known. Despite close relations with the Soviet Union, Finland managed to retain democratic multi-party elections and remained a Western European market economy, building close ties with its Nordic neighbours. While there were some tense moments, Finland pulled it off: in these decades the country made a remarkable transformation from a farm and forest economy to a diversified modern industrial economy featuring high-tech giants like Nokia, and per capita income is now in the world top 15.

After the collapse of the USSR, Finland joined the European Union in 1995, and was the only Nordic state to join the euro currency system at its initiation in January 1999. In 2017, Finland celebrated its 100 years of independence.

Politics

Finland is a republic with a multi-party system. The President had a strong position until the 1980s, after which they gradually have lost most of their formal powers but remain influential. The President, the Parliament, the municipal councils and, since 2022, the "welfare area councils" are elected directly, the three latter in proportional elections (with province-sized electoral districts for the Parliament, no divisions for the two last ones), where votes are cast for individual candidates but aggregated over the party or electoral alliance. The personal votes determine who get a party's (or alliance's) seats. There are also elections for the European Parliament as in all the EU. There have traditionally been three big parties (four since 2011), each with about 20% support, resulting in majority governments of varying coalitions and a search for consensus across most parties for many big questions. There is no constitutional court, but a non-political standing committee of the parliament judging whether proposed new legislation is constitutional and what amendments might be needed. Also, individual judges are free not to apply a law that they deem to be clearly unconstitutional in the context of a specific case.

The large parties as of 2022 are the National Coalition (Kokoomus/Samlingspartiet; right-wing), the Social Democrats (Sosiaalidemokraatit/Socialdemokraterna; centre-left), the True Finns (Perussuomalaiset; conservative nationalistic populists) and the Centre Party (Keskusta/Centern; centre-right, with agrarian background). Other parties include the Left Alliance (left, greenish as of 2022), the Green League (liberal environmentalists), the Swedish People's Party (social liberal centre-right) and the Christian Democrats (Christian conservative right-wing), the former two with a support of some 10%, the latter of about 5%. The established minor parties often get a seat in the government to allow an alliance (formed after the elections) to gain the majority. The National Coalition, Social Democrats and Green League tend to have their support in the cities, while the Centre Party dominates in much of the countryside. The Swedish party dominates among Swedish-speakers, but also has some support across the language barrier.

The concept of right and left has to be seen in the context of Western Europe or the Nordic countries: the Nordic welfare state has a solid support among the people and any rhetoric will be adjusted to accommodate that consensus.

Geography

Finland is not on the Scandinavian peninsula, so despite many cultural and historical links (including the Swedish language, which enjoys co-official status alongside Finnish), it is not considered to be part of Scandinavia. Even Finns rarely bother to make the distinction, but more correct terms that include Finland are the "Nordic countries" (Pohjoismaat, Norden) and "Fennoscandia".

Particularly in the eastern and northern parts of the country, which are densely forested and sparsely populated, you'll find more examples of traditional, rustic Finnish culture. Southern and western Finland, which have cultivated plains and fields, most of the Swedish-speaking and a higher population density, do indeed have very much in common with Scandinavia proper — this can clearly be seen in the capital, Helsinki, which has a lot of Scandinavian features, especially in terms of architecture.

Climate

See also: Winter in the Nordic Countries

Finland has a temperate climate, which is actually comparatively mild for the latitude because of the moderating influence of the Gulf Stream. There are four distinct seasons: winter, spring, summer and autumn. Winter is just as dark as everywhere in these latitudes, and temperatures can (very rarely) reach -30°C in the south and even dip down to in the north, with 0 to −25°C (+35 to −15°F) being normal in the south. Snow cover is common, but not guaranteed in the southern part of the country. Early spring (March–April) is when the snow starts to melt and Finns like to head north for skiing and winter sports. The brief Finnish summer is considerably more pleasant, with day temperatures around +15 to +25°C (on occasion up to +35°C), and is generally the best time of year to visit. July is the warmest month. September brings cool weather (+5 to +15 °C), morning frosts and rains. The transition from autumn to winter in October–December – wet, rainy, sometimes cold, no staying snow but maybe slush and sleet, dark and generally miserable – is the worst time to visit. There is a noticeable difference between coastal and southern areas vs. inland and northern areas in the timing and length of these seasons: if travelling north in the winter, slush in Helsinki often turns to snow by Tampere.

Due to the extreme latitude, Finland experiences the famous midnight sun near the summer solstice, when (if above the Arctic Circle) the sun never sets during the night and even in southern Finland it never really gets dark. The flip side of the coin is the Arctic night (kaamos) in the winter, when the sun never comes up at all in the north (with good chances to see northern lights instead). In the south, daylight is limited to a few pitiful hours with the sun just barely climbing over the trees before it heads down again. In December, Finns compensate by lighting candles and eating confectionery together with some good friend, and enjoying the Christmas season.

Information on the climate and weather forecasts are available from the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

Culture

Buffeted by its neighbours for centuries and absorbing influences from west, east and south, Finnish culture as a distinct identity was only born in the 19th century: "Swedes we are no longer, Russians we do not want to become, let us therefore be Finns."

The Finnish creation myth and national epic is the Kalevala, a collection of old Karelian stories and poems, to a large part from across the (at the time invisible) border to Russian Karelia, collated by Elias Lönnrot in 1835. In addition to the creation the book includes the adventures of Väinämöinen, a shamanistic hero with magical powers. Kalevalan themes such as the Sampo, a mythical cornucopia, have been a major inspiration for Finnish artists, and figures, scenes, and concepts from the epic continue to colour their works.

While Finland's state religion is Lutheranism, a version of Protestant Christianity, the country has full freedom of religion and for the great majority everyday observance is lax or non-existent. Still, Luther's teachings of strong work ethic and a belief in equality remain strong, both in the good (women's rights, non-existent corruption) and the bad (conformity, high rates of depression and suicide). The Finnish character is often summed up with the word sisu, a mixture of admirable perseverance and pig-headed stubbornness in the face of adversity.

Finnish music is best known for classical composer Jean Sibelius, whose symphonies continue to grace concert halls around the world. Finnish pop, on the other hand, has only rarely ventured beyond the borders, but rock and heavy metal bands like Nightwish, Children Of Bodom, Sonata Arctica, Apocalyptica and HIM have become fairly big names in the global heavy music scene and latex monsters Lordi hit an exceedingly unlikely jackpot by taking home the Eurovision Song Contest in 2006.

In the other arts, Finland has produced noted architect and designer Alvar Aalto, authors Mika Waltari (The Egyptian) and Väinö Linna (The Unknown Soldier), and painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela, known for his Kalevala illustrations.

Bilingualism

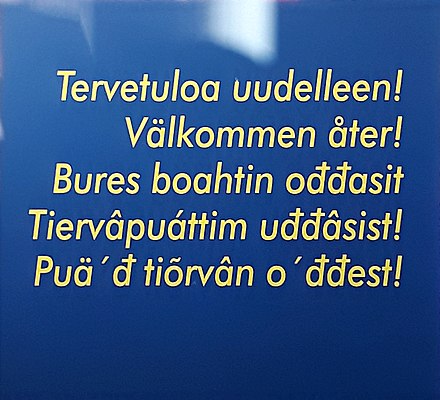

<div style="float:right; margin-left:15px; margin-right:15px; text-align:center"> | Finnish | Swedish | English | | --- | --- | --- | | _-katu_ | _-gata(n)_ | street | | _-tie_ | _-väg(en)_ | road | | _-kuja_ | _-gränd(en)_ | alley | | _-väylä_ | _-led(en)_ | way | | _-polku_ | _-stig(en)_ | path | | _-tori_ | _-torg(et)_ | market | | _-kaari_ | _-båge(n)_ | crescent | | _-puisto_ | _-park(en)_ | park | | _-ranta_ | _-kaj(en)_ | quay | | _-rinne_ | _-brink(en)_ | bank (hill) | | _-aukio_ | _-plats(en)_ | square | </div>Finland has a 5.5% Swedish-speaking minority and is officially bilingual, with both languages compulsory in school. Three Sámi languages (including Northern Sámi), Romani and Finnish sign language are also recognised in the constitution, but are not "national" languages. Maps and transport announcements often give both Finnish and Swedish names, e.g. Turku and Åbo are the same city. This helps the visitor, as English-speakers generally find the Swedish announcement easier to follow, especially if you have a smattering of German. Road signs often flip between versions, e.g. Turuntie and Åbovägen are both the same "Turku Road". This is common in Helsinki and the Swedish-speaking coastal areas, whereas Swedish is far less common inland. Away north in Lapland, you almost never see Swedish, but you may see signage in (mostly Northern) Sami. And if you navigate by Google Map, there's no telling what language it may conjure up.

Although the country was once ruled by a Swedish elite, most Swedish-speaking Finns have always been commoners: fishermen, farmers and industrial workers. The educated class has been bilingual since the national awakening, while population mixing with industrialisation did the rest. In the bilingual areas the language groups mix amicably. Even in Finnish speaking areas, such as Jyväskylä, Pori and Oulu, many Finnish speakers welcome the contacts with Swedish that the minority provides; the few Swedish schools in those areas have many Finnish pupils and language immersion daycare is popular. In politics bilingualism remains contentious: some Finnish speakers see it as a hangover from Swedish rule, while Swedish speakers are concerned at their language being marginalised, e.g. when small Swedish institutions are merged with bigger Finnish ones.

Holidays

See also: Nordic folk culture

Finns aren't typically very hot on big public carnivals; most holidays are spent at home with family. The most notable exception is Vappu on 30th April–1st May, as thousands of people (including the students) fill the streets. Important holidays and similar happenings include:

- New Year's Day (uudenvuodenpäivä and uudenvuodenaatto, nyårsdagen and nyårsafton), January 1. The President's speech, the Vienna concert and the Garmisch-Partenkirchen ski jumping.

- Epiphany (loppiainen, trettondag), January 6. The date coincides with 24 December in the Julian calendar used by the Russian church, contributing to lots of Russian tourists around this time (and thus to many shops being open despite the holiday) – except since they were banned in 2022.

- Easter (pääsiäinen, påsk), variable dates, Good Friday and Easter Monday are public holidays. Tied to this are laskiainen, fastlagstisdag, 40 days before Easter, nominally a holy day that kicks off the Lent, practically a time for children and university students to go sliding down snowy slopes, and Ascension Day (helatorstai, Kristi himmelsfärds dag) 40 days after, just another day for the shops to be closed. If you want to visit an Orthodox service, the one in waiting for the grave to be found empty might be the most special one.

- Walpurgis Night (vappuaatto, valborgsmässoafton) and May Day (vappu, första maj, the Finnish word often written with capital-W), originally a pagan tradition that coincides with a modern workers' celebration, has become a truly giant festival for university students, who wear their colourful signature overalls, white student caps, and roam the streets. Also the graduates use their white student caps between 18:00 at April 30 until the end of May 1st. The latter day people gather to nurse their hangovers at open-air picnics, even if it's raining sleet! Definitely a fun celebration to witness as the students come up with most peculiar ways to celebrate. On 1 May there are also parades and talks arranged by the left-wing parties, and families go out buying balloons, whistles and other market fare. Small towns often arrange an open-air market or an event at a community centre, open to the public.

- Midsummer (juhannus, midsommar), Friday evening and Saturday between June 20th and June 26th. Held to celebrate the summer solstice, with plenty of bonfires, drinking and general merrymaking. Cities become almost empty as people rush to their summer cottages. It might be a good idea to visit one of the bigger cities just for the eerie feeling of an empty city – or a countryside village, where the locals vividly celebrate together. Careless use of alcohol during this particular weekend in the "country of thousand lakes" is seen in Finnish statistics as an annual peak in the number of people died by drowning. Midsummer is the beginning of the Finnish holiday season and in many summer-oriented destinations "on Season" means from the Midsummer until the schools open.

- Independence Day (itsenäisyyspäivä, självständighetsdagen), December 6. A fairly sombre celebration of Finland's independence. There are church services (the one from the cathedral in Helsinki, with national dignities, can be seen on TV), concerts, and a military parade arranged every year in some town. A 1955 movie, The Unknown Soldier, is shown on TV. The most popular event is in the evening: the President holds a ball for the important people (e.g. MPs, diplomats, merited Finnish sportspeople and artists) that the less important watch on TV – over 2 million Finns watch the ball from their homes.

- Little Christmas (pikkujoulu). People go pub crawling with their workmates throughout December. Not an official holiday, just a Viking-strength version of an office Christmas party season. Among the Swedish-speakers the lillajul ("little Christmas") is the Saturday at beginning of Advent and is mostly celebrated among families.

- Christmas (joulu, jul), December 24 to 26. The biggest holiday of the year, when pretty much everything closes for three days. Santa (Joulupukki, Julgubben) comes on Christmas Eve on December 24, ham is eaten and everyone goes to sauna. Christmas Peace is declared in some Finnish cities, the event in Turku with a live audience of some 15,000 and broadcast on TV. See also Winter in the Nordic countries#Christmas.

- New Year's Eve (uudenvuodenaatto, nyårsafton), December 31. Fireworks time!

Most shops and offices are closed on most of these holidays. Public transport stops for part of Christmas and Midsummer; on other holidays, timetables for Sundays are usually applied, sometimes with minor deviations.

Halloween is not an official holiday in Finland. However, it is now very popular with the younger generation. The celebration of Halloween is largely focused in the American way on October 31 or around the next few days. In Finnish history, the closest equivalent to the Celtic-based Samhain festival is known as Kekri. All Saints' Day (pyhäinpäivä, allhelgonadag) is solemnly celebrated by visiting family graves. As the day is a Sunday anyway, it doesn't affect shopping or traffic.

Most Finns take their summer holidays in July, unlike elsewhere in Europe, where August is the main vacation season. People generally start their summer holidays around Midsummer. During these days, cities are likely to be less populated, as Finns head for their summer cottages. Schoolchildren start their summer holidays in the beginning of June and return to school in mid-August. The exact dates vary by year and municipality.

Get in

Since July 2022 there are no COVID-19-related restrictions on entry. Restrictions for travellers from China are planned as of 10 January.

The domestic COVID-19 restrictions were lifted in June. Prevalence is still high as of December 2022, although down from the July figures.

Finland is a member of the Schengen Agreement.

- There are normally no border controls between countries that have signed and implemented the treaty. This includes most of the European Union and a few other countries.

- There are usually identity checks before boarding international flights or boats. Sometimes there are temporary border controls at land borders.

- A visa granted for any Schengen member is valid in all other countries that have signed and implemented the treaty.

- Please see Travelling around the Schengen Area for more information on how the scheme works, which countries are members and what the requirements are for your nationality.

Visa freedom applies to Schengen and EU nationals and nationals of countries with a visa-freedom agreement, for example United States citizens. By default, a visa is required; see the list to check if you need a visa. Visas cannot be issued at the border or at entry, but must be applied at least 15 days in advance in a Finnish embassy or other mission (see instructions). An ID photograph, a passport, travel insurance, and sufficient funds (considered to be at least €30 a day) is required. The visa fee is €35–70, even if the visa application is rejected.

Visa processing times tend to be quite lengthy and might be one of the more stringent ones overall. It's not uncommon to wait for a month or more to get a Finnish visa, so plan and prepare well.

For Russians, tourism isn't a valid reason to enter Finland (because of the Russian war on Ukraine) and multi-entry visas may be retracted. Tourist visas are still granted and valid for certain other types of visits; there are plans to create new visa types for these.

The Finland-Russia border is a Schengen external border, and border controls apply. This border can be crossed only at designated border crossings; elsewhere there is a no-entry border zone on both sides, mostly a few kilometres in width on the Finnish side. Entering the border zones or trying to photograph there will result in an arrest and a fine. The Finnish-Norwegian and Finnish-Swedish borders may be crossed at any point without a permit, provided that you're not carrying anything requiring customs control. Generally, when travelling over the international waters between Finland and Estonia, border checks are not required. However, the Border Guard may conduct random or discretionary checks and is authorised to check the immigration status of any person or vessel at any time or location, regardless of the mode of entry.

As Finland is separated from Western and Central Europe by the Baltic Sea, the common arrival routes (in addition to flights) are via Sweden, with a one-night (or day) ferry passage, via Estonia, with a shorter ferry passage, or from Russia, over the land border. There are also ferries across the Baltic Sea, mainly those from Travemünde in Germany (two nights or two days).

By plane

Because of the Russian war on Ukraine, flights through Russian airspace have been suspended or rerouted. Details are not necessarily updated below.

Finland's main international hub is Helsinki-Vantaa Airport (IATA: HEL) near Helsinki. Finnair and SAS are based there, as is Norwegian Air Shuttle, offering domestic and international flights. Around 30 foreign airlines fly to Helsinki-Vantaa. Connections are good to major European hubs like Munich (MUC), Frankfurt (FRA), Amsterdam (AMS) and London Heathrow (LHR), and transfers can be made via Stockholm (ARN) and Copenhagen (CPH). There are flights from several East Asian cities, such as Beijing, Seoul (ICN), Shanghai and Tokyo, and some destinations in other parts of Asia. In the other direction, New York City is served around the year and Chicago, Miami and San Francisco in the summer season.

International flights to other airports in Finland are scarce (Air Baltic and Ryanair have withdrawn most of their services to regional Finland). To Lapland there are seasonal scheduled flights (Dec–Mar) as well as occasional direct charters (especially in December). There are direct flights all year to Tampere and Turku from a couple of foreign destinations, to Lappeenranta from Bergamo, Vienna and Budapest, to Turku from Belgrade, Gdańsk, Kaunas, Kraków, Larnaca, Skopje, Warsaw, and to Mariehamn, Tampere, Turku and Vaasa from Stockholm.

If your destination is somewhere in Southern Finland, it may also be worth your while to get a cheap flight to Tallinn and follow the boat instructions for the last leg.

By train

The trains from Russia have been suspended, because of the Russian war on Ukraine.

There are no direct trains between Sweden or Norway and Finland (the rail gauge is different), but Haparanda in Sweden is next to Tornio in Finland, just walk across the border. For more trains, continue to Kemi 30 km away. The journey by coach from Swedish trains to Kemi is free with an Eurail/Inter Rail pass. If you instead take a ferry farther south, you mostly get a 50% discount with these passes (on the normal price, you might find cheaper offers).

By bus

Buses are the cheapest but also the slowest and least comfortable way of travelling between Russia and Finland. As of 2022 some of the connections are suspended indefinitely and more might close down with short notice, check!

- Regular scheduled express buses run between Saint Petersburg, Vyborg and major southern Finnish towns like Helsinki, Lappeenranta, Jyväskylä and all the way west to Turku, check Matkahuolto for schedules. St. Petersburg–Helsinki is served 2–4 times daily and takes 7–8 hours.

- Various direct minibuses run between Saint Petersburg's Oktyabrskaya Hotel (opposite Moskovsky train station) and Helsinki's Tennispalatsi (Eteläinen Rautatiekatu 8, one block away from Kamppi). At €15 one-way, this is the cheapest option, but the minibuses leave only when full. Departures from Helsinki are most frequent in the morning (around 10:00), while departures from Saint Petersburg usually overnight (around 22:00).

- There is a daily service between Petrozavodsk and Joensuu.

- There is a service between Murmansk and Ivalo in northern Finland thrice a week (possibly suspended, check).

You can also use a bus from northern Sweden or Norway to Finland.

- Haparanda at the border in Sweden has bus connections to Tornio, Kemi, Oulu and Rovaniemi. See more from Matkahuolto and Haparanda#Get in.

- Eskelisen Lapinlinjat offers bus connections from northern parts of Norway. Some routes, such as Tromsø, in summer only.

- Tapanis Buss has a route from Stockholm to Tornio going along the E4 coastal route. From Tornio it is possible to continue using Finnish long distance buses or trains. See Haparanda#Get in for other connections to the border.

By boat

See also: Baltic Sea ferries

One of the best ways to travel to and from Finland is by sea. The cruise ferries from Estonia and Sweden are giant, multi-story floating palaces with restaurants, department stores and entertainment. There are also more Spartan ropax ferries from Sweden and Germany, and there have been faster and smaller hydrofoils from Tallinn. Cheap prices are subsidised by sales of tax-free booze: a return trip from Tallinn to Helsinki or from Stockholm to Turku, including a cabin for up to four people can go as low as €30. Ordinary tickets are significantly more expensive, though. If travelling by Inter Rail, you can get 50% off deck fares on non-cruises.

The passes over Sea of Åland and Kvarken from Sweden, and Gulf of Finland from Estonia, are short enough for any yacht on a calm day (many also come over the sea from Gotland). As Finland is famous for its archipelagos, especially the Archipelago Sea, coming with small craft is a good alternative. Border controls are not generally required for pleasure craft, unless coming from Russia; however, the Border Guard can discretionarily order individual craft to report to border control. All craft arriving from outside the Schengen area must report to border control (see Boating in Finland#Get in).

Estonia and the Baltic states

Helsinki and Tallinn are only 80 km apart. Viking Line, Eckerö Line and Tallink Silja operate full-service car ferries all year round. Depending on the ferry type travel times are from 2 (Tallink's Star class ferries) to 3½ hours (Tallink's biggest cruise ships). Some services travel overnight and wait outside the harbour until morning.

The Tallink cruise ferry between Tallinn and Stockholm calls at Mariehamn (in the night/early morning). There are no scheduled services from Latvia or Lithuania, but some of the operators above offer semi-regular cruises in the summer, with Riga being the most popular destination.

Germany

Finnlines (dead link: January 2023) operates from Travemünde near Lübeck and Hamburg to Helsinki, taking 27–36 hours one way. These are ropax ferries: primarily intended for freight and lorry drivers, but having some amenities also for normal passengers, including families. They are not party and shopping boats like some other Baltic ferries.

Traffic on this route was more lively in former times, the best example being the GTS Finnjet, which was the fastest and largest passenger ferry in the world in the 1970s. Freight and passengers could be transported between Helsinki and Travemünde in only 22 hours, reaching the rest of continental Europe west of the Iron Curtain much faster than the other (non-air) routes at the time.

Russia

For years scheduled ferry services from Russia have been stop-and-go. As of 2022 connections are suspended because of COVID-19 and the Russian war on Ukraine.

The passenger cruises between Vyborg and Lappeenranta were suspended in 2022, also because of the war. The Saimaa Canal can still be used to reach Saimaa and the lake district by own vessel.

If coming by yacht from Russia (or via, as in using the Saimaa Canal), customs routes have to be followed, see Boating in Finland#Get in.

Sweden

Both Silja (Tallink) and Viking offer overnight cruises from Stockholm to Helsinki and overnight as well as daytime cruises to Turku, all usually calling in the Åland islands along the way, in either Mariehamn or Långnäs. These are some of the largest and most luxurious ferries in the world, with as many as 14 floors and a whole slew of restaurants, bars, discos, pool and spa facilities, etcetera. The cheaper cabin classes below the car decks are rather Spartan, but the higher sea view cabins can be very nice indeed. As Åland is outside the EU tax area, the ferries can operate duty-free sales. (Tallink is cutting down their service to Turku in September 2022, see Turku.)

Due to crowds of rowdy youngsters aiming to get thoroughly hammered on cheap tax-free booze, both Silja and Viking do not allow unaccompanied youth under 23 to cruise on Fridays or Saturdays. The age limit is 20 on other nights, and 18 for travellers not on same-day-return cruise packages. Silja does not offer deck class on its overnight services, while Viking does.

With Viking Line it often is cheaper to book a cruise instead of "route traffic". The cruise includes both ways with or without a day in between. If you want to stay longer you simply do not go back – it might still be cheaper than booking a one-way "route traffic" ticket. This accounts especially to last minute tickets (you could, e.g., get from Stockholm to Turku for around 10€ over night – "route traffic" would be over 30€ for a cabin with lower quality).

In addition to the big two, FinnLink (Finnlines) offers the cheapest car ferry connection of all from Kapellskär to Naantali, some of the services calling also in Åland (from €60 for a car with driver). These are much more quiet, primarily catering to lorry drivers.

For Åland there are some more services, to Mariehamn or Eckerö, by Viking and Eckerölinjen.

There is also a car ferry connection between Umeå and Vaasa (Wasa line; 4 hours), without taxfree sales, but trying to achieve the same feeling as on the southerly routes.

The latest addition, in 2022, is Stena Line with a daily connection from Nynäshamn south of Stockholm to Hanko on the south coast, with two ropax ferries, i.e. mostly for freight but with some passenger capacity, only for those travelling with a vehicle. Basic fares in this route also do not include a cabin or lounge.

By car

Sweden

The easiest ways to get by car from Sweden to Finland is a car ferry (except in the far north). The European Route E18 includes a ferry line between Kapellskär and Naantali. There are four daily cruise ferries on the nearby pass Stockholm–Turku (two of them overnight) and two on the longer pass Stockholm–Helsinki (overnight). There is also a daily ferry from Nynäshamn to Hanko. Farther north there is the Blue Highway/E12, with car ferry (4 hours) from Umeå to Vaasa, where E12 forks off to Helsinki as Finnish national highway 3.

There are also land border crossings up in Lapland in Tornio (E4), Ylitornio, Pello, Kolari, Muonio and Karesuvanto (E45).

Norway

European Routes E8 and E75 (and some national roads) connect northern Norway with Finland. There are border crossings at Kilpisjärvi, Kivilompolo (near Hetta), Karigasniemi, Utsjoki, Nuorgam and Näätämö. For central and southern parts of Norway, going through Sweden is more practical, e.g. by E12 (from Mo i Rana via Umeå) or E18 (from Oslo via Stockholm or Kapellskär).

Russia

European route E18 (in Russia: route A181, formerly part of M10), goes from Saint Petersburg via Vyborg to Vaalimaa/Torfyanovka border station near Hamina. From there, E18 continues as Finnish national highway 7 to Helsinki, and from there, along the coast as highway 1 to Turku. In Vaalimaa, trucks will have to wait in a persistent truck queue, but this queue does not directly affect other vehicles. There are border control and customs checks in Vaalimaa and passports and Schengen visas, if applicable, will be needed.

From south to north, other border crossings can be found at Nuijamaa/Brusnichnoye (Lappeenranta), Imatra/Svetogorsk, Niirala (Tohmajärvi, near Joensuu), Vartius (Kuhmo), Kuusamo, Kelloselkä (Salla) and Raja-Jooseppi (Inari). All except the first are very remote, and most of those open in daytime only.

Estonia

Some of the ferries between Tallinn and Helsinki take cars. They form an extension to European route E67, Via Baltica, which runs from the Polish capital Warsaw, via Kaunas in Lithuania and Riga in Latvia, to the Estonian capital Tallinn. The distance from Warsaw to Tallinn is about 970 kilometres, not including any detours. There is a car and cargo ferry service from Paldiski to Hanko.

By bicycle

Bikes can be taken on the ferries for a modest fee. You enter via the car deck, check when to show up. As you will leave the bike, have something to tie it up with and bags for taking what you need (and valuables) with you.

There are no special requirements on the land borders with Norway and Sweden.

In 2016, Finnish Border Agency did forbid crossing the border by bicycle over the northernmost checkpoints from Russia (Raja-Jooseppi and Salla), the restriction has probably expired, but check! The southern border stations were apparently not affected.

On the trains from Russia (suspended in 2022), the bikes have to be packed (100 cm x 60 cm x 40 cm).

By foot

Walk-in from Sweden and Norway is allowed anywhere (unless you have goods to declare, which can probably be handled beforehand), but crossing the Russian border by foot outside designated crossings is not. The border is well marked and well patrolled, so expect to be arrested and fined if you try it.

Get around

Finland is a large country and travelling is relatively expensive. Public transportation is well organised and the equipment is always comfortable and often new, and advance bookings are rarely necessary outside the biggest holiday periods, but buying tickets on the net a few days in advance (or as soon as you know your plans) may give significantly lower prices.

There are several route planners available. VR and Matkahuolto provide timetable service nationwide for trains and coaches, respectively, and there are several regional and local planners. As of 2020, Google Maps and Apple Maps have coverage nationally. opas.matka.fi includes train traffic, domestic flights, local transport of many cities and towns and public service obligation traffic (i.e. services offered on behalf of the government) in the countryside. Matkahuolto Reittiopas is focused on local, regional and long-distance buses and trains. There are deficiencies in most or all of the planners, so try different names (perhaps an intermediate town, or one which should be later on the same coach line) and main stops if you don't get a connection, and do a sanity check when you get one. You might also want to check more than one when services shown are sparse or complicated. Knowing the municipality and the name in both Finnish and Swedish is useful. Sometimes the local connections are unknown to the digital services.

"Street addresses" work with many electronic maps also for the countryside. "Street numbers" outside built-up areas are based on the distance from the beginning of the road, in tens of metres, with even numbers on the left hand side: "Metsätie 101" is about a kilometre from the junction, on the right hand side, distance from the named road to the house not counted. Many roads change names at municipality borders; what is Posiontie in Ranua becomes Ranuantie in Posio. An address of "Rantakatu 12–16 A 15" means lots 12, 14 and 16 on that street, stairwell A (or house A), flat number 15. Most map services know only the individual lots. "Rantakatu 12 a" means the first lot of an original lot 12 that was split. The distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters is ignored in some applications.

By plane

Flights are the fastest but traditionally also the most expensive way of getting around. The new low-cost airliners however provide prices even half of the train prices in the routes between north and south. In some cases it may even be cheaper to fly via Riga than take a train. Finnair and some smaller airlines still operate regional flights from Helsinki to places all over the country, including Kuopio, Rovaniemi, Ivalo and Vaasa. It's worth booking in advance if possible: on the Helsinki–Oulu sector, the country's busiest, a fully flexible return economy ticket costs a whopping €251 but an advance-purchase non-changeable one-way ticket can go as low as €39, less than a train ticket. Finnair has cheaper fares usually when you book at least three week before your planned trip and your trip includes at least three nights spent in destination or one night between Friday and Saturday or Saturday and Sunday. You may also be able to get discounted domestic tickets if you fly into Finland on Finnair and book combination ticket directly to your final destination. Finnair also has a youth ticket (16–25) and senior ticket (age above 65 years or pension decision) that is substantially cheaper and fixed price regardless of when you book.

Flying makes most sense when there is a suitable transfer. By going to Helsinki from elsewhere for the flight, and transferring to the airport in both ends, you often lose any time you win on flying. Flying may make sense also when rail connections are convoluted or the flight is long, such as to Ivalo. To Oulu or Rovaniemi the flight is considerably faster, but with an overnight train available that point may be moot.

There are two major airlines selling domestic flights:

- Finnair, the biggest by far. Serves nearly all of the country, with some flights operated by their subsidiary Nordic Regional Airlines..

- Norwegian Air Shuttle flies from Helsinki to Oulu and Rovaniemi.

In addition there's a handful of smaller airlines, often just flying from Helsinki to one airport each. The destinations served are often easy to reach by train, bus and car, making flights unprofitable, wherefore companies and services tend to come and go.

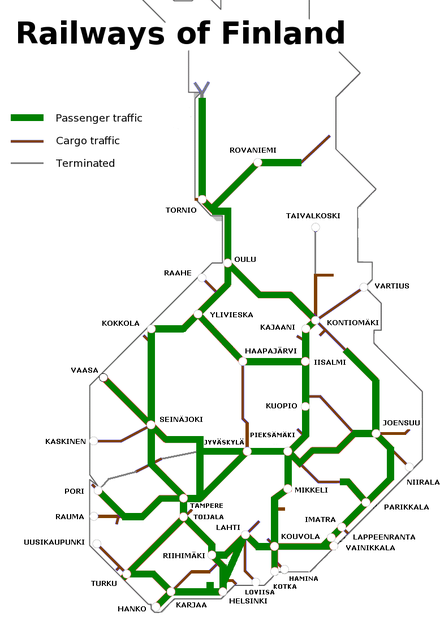

By train

The strike ended on 24 March 2023 and trains are running, but there may be irregularities. Check latest information.

VR (Valtion Rautatiet, "State's Railways") operates the railway network. Trains are usually the most comfortable and fastest method of inter-city travel. From Helsinki to Tampere, Turku and Lahti, there are departures more or less every hour in daytime.

The following classes of service are available:

- Pendolino tilting trains (code S) often fastest; children and pets in normal cars

- InterCity (IC) and InterCity2 (IC2) express trains; the latter are two-storey, mostly with a family car with a playing corner for children.

- Ordinary express (pikajuna, P), old cars; some night trains and connections on remote routes

- Local and regional trains (lähiliikennejuna, lähijuna or taajamajuna), no surcharge, quite slow

While differences between Pendolino, IC and express trains aren't that crucial – if you need specific facilities you should check anyway – rules for regional trains (about pets, bikes and tickets) may differ from those on the long-distance trains, and some regional trains travel quite far from Helsinki.

The trains are generally very comfortable, especially the intercity and long distance services, which (depending on route and type of train) may have restaurant and family cars (with a playing space for children), power sockets, and free Wi-Fi connection. The accessible toilets on IC2 trains double as family rooms. Check the services of individual trains if you need them, e.g. facilities for families and wheelchair users vary considerably. Additional surcharges apply for travel in first class, branded "Extra" on some trains, which gets you more spacious seating, newspapers and possibly a snack. Wi-Fi is sometimes overloaded when many use the journey time for work, such as on morning trains to Helsinki.

Formally two large pieces of luggage (80×60×40 cm) are allowed for free in the Finnish trains, in addition to small hand luggage, and pram or wheelchair if applicable. Also a ski bag can be taken into your cabin for free. In practice, no one will check the allowance unless you cause trouble. For skis (max 30×30×220 cm), snowboards and other additional luggage (max 60×54×195 cm) transported in the luggage compartment €5/piece is charged.

Overnight sleepers are available for long-haul routes and very good value. Pillows, sheets and blankets are provided. The modern sleeper cars to Lapland have 2-berth cabins, some of which can be combined as a pair for a family. There are en suite showers in the upper floor cabins in the modern overnight trains, the base-floor cabins use shared showers. In the 3-berth cabins in the old "blue" sleeper cars there are no showers, only a small sink in the cabin, but some more overhead luggage space; these cars are nowadays mostly used as supplement in the "P" trains in the busiest holiday periods. In each modern Finnish sleeper car, one cabin is for a disabled person and his or her assistant. If you take a "P" train with both new and old cabins, check that you get the cabin you want. An overnight journey from Helsinki to Lapland in a sleeper cabin costs about €150–250 for two people (as of 2022; you always book all the cabin).

The restaurant cars mostly serve snacks, coffee and beer. On some routes (such as those to Lapland) you can get simple real meals (€10–13.50). Shorter intercity routes usually just have a trolley with snacks, coffee, beer etc. Drinking alcoholic beverages you brought yourselves is not allowed. Own food at your seat should be no problem as long as you don't make a mess or spectacle out of it; bringing packed meals, other than for small children, has become rare.

Seniors over 65 years old and students with Finnish student ID (ISIC cards etc. not accepted) get 50 % off. If booking a few days (better: at least two weeks) in advance on the net you may get cheaper prices. Children younger than 10 years travel for free in sleeper cabins if they share a bed with somebody else (bed width 75 cm, safety nets can be ordered, using a travel bed is allowed if it fits nicely). Otherwise children aged 4–16 pay a child fee on long-distance trains, those aged 7–16 on commuter trains, usually half the ordinary price. Carry your ID or passport to prove your age.

Pets can be taken on trains (€5), but seats must be booked in the right compartments. If your pet is big, book a seat with extended legroom (or, on some trains, a separate seat for the pet). The pets travel on the floor (a blanket can be useful; bring water), other than for dogs a cage is mandatory. Vaccination etc. should be in order. For regional transport the rules are different. The sleeper trains have some cabins for passengers with pets (probably one upstairs and one halfway up in each modern sleeper car, some cabins in the older sleeper cars and probably some day department). For night trains, ask the conductor about stops where you can get out with your dog. Don't leave pets in your car.

Finland participates in the Inter Rail and Eurail systems. Residents of Europe can buy InterRail Finland passes offering 3–8 days of unlimited travel in one month for €109–229 (adult 2nd class), while the Eurail Finland pass for non-residents is €178–320 for 3–10 days. You would have to travel a lot to make any of these pay off though; by comparison, a full-fare InterCity return ticket across the entire country from Helsinki to Rovaniemi and back is €162. The price for a typical 2-hr journey, such as between Helsinki, Turku and Tampere, is about €20.

Train tickets can be purchased online, from ticketing machines on mid-sized and large stations, from manned booths on some of the largest stations and e.g. from R kiosks (not all tickets). A fee of €1–3 applies when buying over the counter or by phone. There are usually cheaper offers if you buy several days in advance, to get the cheapest tickets, buy them at least two weeks in advance. A seat is included in the fare of these tickets. During the COVID-19 pandemic, seats must be reserved, i.e. tickets bought, in advance. On the regional trains in the capital region there is no ticket sale in normal times either.

This means that for walk-up travel at many mid-sized stations, you'll need to buy a ticket from the machine. This is easier if no-one tries to assist you! Otherwise, thinking to be helpful, they'll press Aloita and you'll be faced by a screen asking you to choose between Aikuinen, Eläkeläisen and Lapsi. So spurn their help, wind back to the beginning and press "Start" to get the process in English, including the bank card reader instructions. Or if you're feeling adventurous you can press Börja since you can figure out whether you're vuxen, pensionär or barn, but you'll have to choose "Åbo" to get a ticket to Turku. Larger machines take cash, but most provincial stations have only small ones for which you need a debit/credit card with chip.

The selling procedure offers a seat, but you can chose one yourself if you want. Usually half of the seats face forward, half of them backward. Seats with a wall behind them have less legroom when reclined, and don't recline as much. You may want to check the options on IC2 trains especially if you are a group or want privacy (four seats with a table in-between, cabins for two or four etc.). On most other trains options are limited.

In some situations your group or voyage does not make sense to the booking system (e.g. if you are a group and have a pet, it might believe you have one each). There are usually tricks to fool the system to allow what you want to do, but unless you find a solution, you might want to book by phone, to leave the problem to somebody more experienced.

Generally, the trains are most crowded at the beginning and end of the weekend, i.e. Friday and Sunday evening. Shortly before and at the end of major holidays like Christmas/New Year and Easter, trains are usually very busy, with car-and-sleeper tickets for the most popular services sold out immediately when booking opens. If you try booking for these days at a late time, you may find the seat you reserve to be among the least desirable, such as without recline – and many services sold out altogether.

While VR's trains may be slick, harsh winter conditions and underinvestment in maintenance mean that delayed trains are not uncommon, with the fancy Pendolinos particularly prone to breaking down. Also much of the network is single-track, so delays become compounded as oncoming trains have to wait in the passing loop. As in the rest of the EU, you'll get a 25% refund if the train is 1–2 hours late and 50% if more. There is real-time train traffic data for every train station in Finland available on the net and in an iOS app.

By bus

There are coach connections along the main roads to practically all parts of Finland. This is also the only way to travel in Lapland, since the rail network doesn't extend to the extreme north. Connections may be scarce between the thoroughfares.

Long haul coaches are generally quite comfortable, with toilets, reclining seats, AC, sometimes a coffee machine and perhaps a few newspapers to read (often only in Finnish, though). Wi-Fi and power outlets (USB or 230 V) are getting common. Some long-haul services stop at an intermediate destination long enough for you to buy a sandwich or eat an ice cream. Coaches seldom restrict the amount of luggage. They have fees for luggage transport, but these are generally not invoked for any you would carry. Bulky luggage is usually placed in a separate luggage compartment, at least if the coach is more than half-full.

There are many operators, but Matkahuolto maintains some services across companies, such as timetables (see below), ticket sale and freight. Their browser-based route planner, with address based routing for coaches, is available (sometimes useful, but often suggests convoluted connections despite there being direct ones). Their Routes and Tickets mobile app also has address-based routing and a ticket purchase option. Some regional public service obligation bus routes are missing. They can be found in the opas.matka.fi route planner, and often from the local bus company, the web page of the municipality (often well hidden in Finnish only) or similar. There are Matkahuolto service points at more or less every bus station, in small towns and villages often by cooperation with a local business. Although the staff is generally helpful, they and their tools may not know very much about local conditions in other parts of the country; checking with locals (such as the local host or local bus company) for any quirks is sometimes advantageous.

For the Matkahuolto main page search results, click (i) for a service, and the link that appears, to get more information on it, including a stop list and days of validity. For most services all stops are listed, with a Here map available; for non-express services sometimes only part of the stops are listed. The main search page doesn't find routes that include transfers, and is quite particular about start and end points (using the city name rather than the bus station can help in cases where the bus starts from elsewhere). Especially the English interface often uses Finnish names also for Swedish-speaking towns – it usually finds the Swedish ones, but might tell only the Finnish name. Searching in Swedish often helps in those cases.

Most coaches between bigger towns are express services (pikavuoro/snabbtur), having fewer stops than the "standard" (vakiovuoro/reguljär tur) coaches, near extinction on some routes. Between some big cities there are also special express (erikoispikavuoro/express) coaches with hardly any stops between the cities. Using coaches to reach the countryside you should check not only that there are services along the right road, but also that any express service you are going to use stops not too far away from where you intend to get off or on, and that any service runs on the right day of the week. Non-express services have stops at most a few kilometres apart.

Coaches are generally slightly higher priced than trains, although on routes with direct train competition they can be slightly cheaper. Speeds are usually slower than trains, sometimes very much so (from Helsinki to Oulu), sometimes even faster (from Helsinki to Kotka and Pori). On many routes, though, coaches are more frequent, so you may still get to your destination faster than if you wait for the next train. Tickets can be bought in advance (bargains are possible on some routes), with the seldom used option to reserve seats, although paying to the driver is common (there are few if any conductors left). Credit and debit cards should be accepted on the main express and long-haul services (and when buying tickets in advance), on "regular" services on short distances you are more likely to need cash.

Pets are usually accepted on coaches as well as buses (except on Onnibus), but not very common. In buses, bigger dogs often travel in the area for prams and wheelchairs. There is a fee for some pets on some services (Koiviston auto: €5 in cash unless they can fit on your lap).

Onnibus offers a cheaper alternative (often €5–10 even for long rides if bought early enough) with double-deckers on routes between major cities in Finland ("Onnibus mega"), and has near monopoly on some of these routes. Tickets must be bought online as they do not accept cash, with cash it is possible to buy Onnibus tickets only from R-kioski and Matkahuolto partners. Online tickets can be bought from Matkahuolto, but other Matkahuolto tickets are not accepted. Passengers need to be on the stop beforehand (15 min recommended), bikes and pets are not accepted, and 12–14 years old children can travel independently with written consent from their parent or guardian using Onnibus's form; otherwise children need to be accompanied by somebody at least 15 years old. Onnibuses include free unencrypted Wi-Fi and 220 V power sockets. The general standard is lower than on other coaches and there is less legroom than in any other buses in Finland. Also the overhead racks are tight, so put everything you do not need in the luggage compartment (one normal-size 20 kg item or according to special rules). Note that the routes do not necessarily serve the centres of intermediate destinations; often they have their stop by the thoroughfare some distance away.

Onnibus also has normal coaches, by themselves or by cooperation ("Onnibux flex"). Standard and prices on these are mostly the same as usually on coaches, not those of Onnibus mega. Onnibus recommends reserving 1½ or 2½ hr for transfers not included on their web site.

Discounts

Senior discounts are for those over 65 years old or with Finnish pension decision.

As with trains, student discounts are available only for Finnish students or foreign students at Finnish institutions. You need either a Matkahuolto/VR student discount card (€5) or a student card with the Matkahuolto logo.

For coaches, children aged 4–11 pay about half the price (infants free), juniors (12–16) get a reduction of up to 30 % or 50 % on long non-return trips. On city buses age limits vary from one city or region to another, often children fees apply for 7–14 years old. An infant in a baby carriage gives one adult a free ride in e.g. Helsinki and Turku (but entering may be difficult in rush hours).

You can get the BusPass travel pass from Matkahuolto, which offers unlimited travel for a specified time, priced at €149 for 7 days and €249 for 14 days. The pass is not accepted by Onnibus.

Local transport

Local transport networks are well-developed in Greater Helsinki, Tampere, Turku, Oulu, Kuopio, Jyväskylä and Lahti. In other big towns public transport networks are often usable on workdays, but sparse on weekends and during the summer, while many small towns only have rudimentary services. For information about local transport in cities and some regions around Finland, see the link list provided by Matkahuolto (in Finnish; scroll to the bottom of the page).

In the countryside there are sometimes line taxis (kutsutaksi), paratransit (palvelulinja, palveluliikenne) or similar arrangements, where the municipality sponsors taxis driving by schedule, but only when the service has been requested. Usually you contact the taxi company the day before to ask for the service and pay according to normal coach or bus fares. Sometimes the taxi can deviate from the route to pick you up from a more convenient point or drive you to your real destination. The added distance is sometimes included, and sometimes paid as a normal taxi voyage (depending on length, municipality and other circumstances). These services are sparse (from a few times daily to weekly) and schedules are made to suit the target audience, often the elderly, but can be the only way to reach some destinations for a reasonable price without one's own vehicle. Some school buses also take outsiders, and sometimes what seems to be a normal bus connection is in fact such a school bus, open for others to use.

The dial-a-ride services in many sparsely populated areas typically drive twice weekly according to an approximate timetable, sometimes doing detours to fetch passengers from their homes (don't expect a fast drive). Mostly these go to a municipal centre in the morning and return in the afternoon, allowing people to visit the healthcare centre, the library, shops and the like. The rides have to be ordered in advance, often the preceding day, and you can check details when calling the driver. The price is about that of a normal bus ticket, i.e. orders of magnitude cheaper than a taxi ride, and the ride may give insights in local life tourists seldom get otherwise, at least if you understand the local language (passengers chatting with the driver is not uncommon).

There are also route planners covering many regions: Opas.matka.fi covers most cities (Helsinki, Hämeenlinna, Iisalmi, Joensuu, Jyväskylä, Järvenpää, Kajaani, Kotka, Kouvola, Kuopio, Lahti, Lappeenranta, Mikkeli, Oulu, Pieksämäki, Pori, Rovaniemi, Salo, Seinäjoki, Tampere, Turku, Vaasa, Valkeakoski, Varkaus). Some of the remaining cities are included in the Matkahuolto Route Planner (Hyvinkää, Kemi, Kokkola, Lohja, Loviisa, Porvoo, Raahe, Rauma, Riihimäki, Savonlinna, Tornio).

As for smartphone apps, Nysse and Moovit have a route planner for local transport services of many cities (Helsinki, Hämeenlinna, Iisalmi, Joensuu, Jyväskylä, Kajaani, Kokkola, Kotka, Kouvola, Kuopio, Lahti, Lappeenranta, Mikkeli, Oulu, Pori, Rovaniemi, Sastamala, Seinäjoki, Tampere, Turku, Vaasa and Varkaus).

General advice

Both coaches and city buses are stopped for boarding by raising a hand at a bus stop (blue sign for coaches, yellow for city buses; a reflector or source of light, such as a smartphone screen, is useful in the dusk and night). Whether stops for regional buses are classified as coach or bus stops depends on municipality and the phase of the moon, and can vary between similar lines. In some rural areas, such as northern Lapland, you may have luck also where there is no official stop (and not even official stops are necessarily marked there). You pay or show your ticket to the driver (or to the machine near the driver). On buses, those with pram or wheelchair usually enter through the middle door. On coaches, the driver will often step out to let you put most of your luggage (including prams) in the luggage compartment – have what you want to have with you in a more handy bag.

Ring the bell by pushing a button when you want to get off, and the bus will stop at the next stop. Often the driver knows the route well and can be asked to let you off at the right stop, and even if not (more common now, with increased competition), drivers usually try their best. This works less well though on busy city buses.

Local and regional transport outside cities often uses minibuses or minivans instead of normal buses. Don't miss them just because they don't look like what you expected.

By boat

See also: Boating in Finland

As a country with many lakes, a long coast and large archipelagos, Finland is a good destination for boating. There are some 165,000 registered motorboats, some 14,000 sailing yachts and some 600,000 rowing boats and small motorboats owned by locals, i.e. a boat on every seventh Finn. If you stay at a cottage, chances are there is a rowing boat available.

Yachts and motorboats are available for charter in most bigger towns at suitable waterways. You may also want to rent a canoe or kayak, for exploring the archipelagos, canoeing along calm rivers or going down rapid-filled ones.

By ferry

In summertime, lake and archipelago cruises are a great way to see the scenery of Finland, although many of them only do circular sightseeing loops and thus aren't particularly useful for getting somewhere. Most cruise ships carry 100–200 passengers (book ahead on weekends!), and many are historical steam boats. Popular routes include Turku–Naantali, Helsinki–Porvoo and various routes on Saimaa and the other big lakes. Child tickets often have lower age limits than on other kinds of transport (such as 3–12 years).

The archipelago of Åland and the Archipelago Sea have many inhabited islands dependant on ferry connections. As these are maintained as a public service they are mostly free, even the half-a-day lines. Some are useful as cruises, although there is little entertainment except the scenery. These are meant for getting somewhere, so make sure you have somewhere to sleep after having got off.

There is a distinction between "road ferries" (yellow, typically on short routes, with an open car deck and few facilities), which are regarded as part of the road network and free, and other ferries (usually with a more ship-like look and primarily serving car-less passengers). Whether the latter are free, heavily subsidised or fully paid by passengers varies. See Archipelago Sea for some discussion. Åland has its own system, see Åland#Archipelago ferries.

By car

Main article: Driving in Finland

<gallery width="275px" widths="50px" heights="50px" perrow="3" style="float: right"> File:Finland road sign C17.svg|No entry File:Finland road sign B4.svg|Priority for oncoming traffic File:Finland road sign C34-40.svg|Speed limit for zone </gallery>Traffic drives on the right. There are no road tolls or congestion charges. From February 2018, driving licences of all countries for ordinary cars are officially accepted in Finland. The only requirement is that the licence is in a European language or you have an official translation of it to Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, German, English or French. A foreign-registered car may be used in Finland for up to six months. A longer stay requires registering it locally and paying a substantial tax to equalise the price to Finnish levels.

Car hire in Finland is expensive, with rates generally upwards of €80/day, although rates go down for longer hire. See Driving in Finland#Costs.

Main roads are usually fairly well maintained and extensive, although motorways are limited to the south of the country and near the bigger cities. Local roads may to some extent suffer from cracks and potholes, and warnings about irregularities in the pavement of these roads are seldom posted.

Look out for wild animals, particularly at dawn and dusk. Collisions with moose (frequently lethal) are common countrywide, deer cause numerous collisions in parts of the country, and semi-domesticated reindeer are a common cause of accidents in Lapland. Try to pass the rear end of the animal to let it escape forward. Call the emergency service (112) to report accidents even if you are OK, as the animal may be injured.

VR's overnight car carrier trains are popular for skipping the long slog from the south up to Lapland and getting a good night's sleep instead: a Helsinki–Rovaniemi trip (one way) with car and cabin for 1–3 people starts from €215.

A few unusual or unobvious rules to be aware of:

- Headlights or DRLs are mandatory even during daylight. New cars usually come with headlight-related automatics which do not always work properly, so double check your car's behavior and use manual toggles if necessary. This is especially important in the dark Finnish winter.

- Always give way to the right, unless signposted otherwise. The concept of minor road refers only to exits from parking lots and such (a decent rule of thumb is whether the exit crosses over a curb). Nearly all intersections are explicitly signposted with yield signs (either the stop sign or an inverted triangle); watch for the back of the yield sign on the other road. Major highways are often signposted with an explicit right of way (yellow diamond with white borders).

- Turning right on red at traffic lights is always illegal. Instead, intersections may have two sets of traffic lights, one with regular circular lights and the other displaying arrows. A green arrow light also means there is no crossing traffic or pedestrians in the indicated direction.

- Times on signage use the 24h clock with the following format: white or black numbers are for weekdays, numbers in parentheses for Saturdays and red numbers for Sundays and public holidays; e.g. "8–16" in white means M–F 8AM–4PM. If the numbers for Saturdays and Sundays are absent, the sign does not apply on weekends at all.

- Trams (present in Helsinki and Tampere) always have the right of way over other vehicles, but not over pedestrians at zebra crossings. You do not want to crash into one.

- Vehicles are required by law to stop at zebra crossings if a pedestrian intends to cross the road or if another vehicle has already stopped to (presumably) give way. Unfortunately, this sometimes causes dangerous situations at crossings over multiple lanes since not all drivers follow the rule properly. Many pedestrians are aware of this and "intend" to cross the road only when there is a suitable gap in the traffic, but you are still required to adjust your speed to be able to stop in case. Use your best judgement and watch out for less careful drivers.

- Using seat belts is mandatory. Children under 135 cm tall must use booster seats or other safety equipment (the requirement is waived for taxis, except for children under 3 years of age).

Finnish driving culture is not too hazardous and driving is generally quite safe.

Winter driving can be risky, especially for drivers unused to cold weather conditions. The most dangerous weather is around freezing, when slippery but near-invisible black ice forms on the roads, and on the first day of the cold season, which can catch drivers by surprise. Studded winter tyres are allowed (for normal cars, not heavy vehicles) November–March and "when circumstances require", with a liberal interpretation, such as in soon being en route to wintry Lapland. Winter tyres (studded or not) are compulsory in wintry conditions November–March.

Speed limits default to 50 km/h in built-up areas (look for the yellow-black coloured sign with a town skyline) and 80 km/h elsewhere. Other limits are always signposted. Major highways often have a limit of 100 km/h, with motorways up to 120 km/h. Some roads have their limits reduced in the winter for safety.

A blood alcohol level of over 0.05 % is considered drunk driving. Finnish police strictly enforce this by random roadblocks and sobriety tests.

If you are driving at night when the petrol stations are closed (many close at 21:00), always remember to bring some cash. Automated petrol pumps in Finland in rare occasions do not accept foreign credit/debit cards, but you can pay with Euro notes. In the sparsely-populated areas of the country, distances of 50 km and more between gas stations are not unheard of, so don't gamble unnecessarily with those last litres of fuel.

By taxi

Taxis are widely available and comfortable, although in the countryside night you may nowadays be out of luck (call in advance). The taxi market was largely deregulated in 2018, causing a significant rise in already expensive prices – and cut income for the drivers. Most companies have a flag fall of €4–9 (differing between daytime in weekdays and nights and weekends) and the meter ticking up by €2–3 per km or so (including a time based fare of around €1/min). Fares have to be clearly posted; while comparing price schemes is difficult, getting ripped off is rare. Using the meter is not mandatory, but by law any fixed fares have to be stated in advance and you have to be warned if the fare might exceed €100.

Once mostly plush Mercedes sedans, taxis can now come in any colour or shape, but they have a yellow taxi sign on the roof (usually with the spelling "TAKSI"), lit when the car is vacant. A normal taxi will carry 4 passengers and a moderate amount of luggage. For significant amounts of luggage, you can order a farmari taxi, an estate/wagon car with a roomier luggage compartment. There is also a third common type of taxi available, the tilataksi, a van which will comfortably carry about 8 people (if you ask for one, you are often charged for 5+ people, but not if you just happen to get one). Tilataksis are usually equipped for taking also a person in wheelchair (ask specifically if you need that service, and prepare for a surplus fee).

If you want child seats, mention that when ordering, you may be lucky. Transporting a child under 3 years of age without an appropriate device is illegal.

The usual ways to get a taxi are to find a taxi rank, order by phone or, increasingly, use a smartphone app (there is often also a similar web page). The apps and we pages usually tell you the total fare (an estimate or a fixed price based on estimates). Street hailing is legal but uncommon, there just aren't that many empty cabs driving around. Any pub or restaurant can also help you get a taxi, expect to pay €2 for the call.

Apps and call centres with taxis available in many cities include:

- Taksi Helsinki. Uses the Valopilkku smart phone app. 2019-08-27

- 02 Taksi, +358 20-230 (€1.25/call+€3/min). Call centre and smart phone app offers address based routing and gives price offers from one or more taxi companies (mainly big companies, i.e. useful mostly in cities, towns and around them). Price or price logic told when booking. 2021-08-25

- Menevä, +358 50-471-0470 (head of office), info@meneva.fi. Smart phone app offers address based routing and calculates price according to them. 2022-01-04

In city centres, long waiting times can be expected in Friday and Saturday nights. The same is true at ferry harbours, railway stations and the like when a service arrives; there is usually a queue of taxis when the ferry arrives, but with all filled up it takes a while before any of them return. It is not uncommon to share a taxi with strangers, if going towards the same general direction. At airports, railway stations and other locations from where many people are going to the same direction at the same time, there may also be kimppataksi minivans publicly offering rides with strangers. They are as comfortable as other taxis and will leave without much delay.

In the countryside, there may only be a single taxi company and they may have to drive a long way to get to you, so pre-booking is strongly recommended if you need to catch a train or flight, or you need one in the night (when no driver might be awake to answer a call). Calling a local driver is safer than booking through a call centre, which might not find any driver when the time is come. For a short trip in a remote location, you might want to tip generously, as the fare doesn't cover the fetching distance. Taksit.fi is an (incomplete) catalogue for finding local taxi companies. For those not listed, check locally.

By ridesharing

Uber operates in Helsinki and sparsely in a few other cities. They are formally taxis.

For inter-city trips, you can try your luck on peer-to-peer ridesharing services:

- kyydit.net – Carpooling site with search engine

- kimppa.net – Oldest and most retro looking carpooling site in Finland

By thumb

Hitchhiking is possible, albeit unusual, as the harsh climate does not exactly encourage standing around and waiting for cars. The thumb-up sign is the one to use. Spring and summer offer long light hours, but in the darker seasons you should plan your time. The most difficult task is getting out of Helsinki.

Many middle age and elderly people hitchhiked when they were young, but in the last decades high standards of living and stories about abuse have had a deterring effect. The highway between Helsinki and Saint Petersburg has a high percentage of Russians among truck drivers. See also Finland article on Hitchwiki.

Pedestrians walking in the dark on shoulders of unlit roads are required by law to use safety reflectors. Their use is generally recommended, since the visibility of pedestrians with reflectors improves greatly. Controlled-access highways (green signs) are off limits for pedestrians.

By bicycle

Most Finnish cities have good cycleways especially outside the centres, and taking a bike can be a quick, healthy and environmentally friendly method of getting around locally. Farther from cities, where the cycleways end, not all major roads allow safe biking. You can often find suitable quiet routes, but sometimes this requires an effort. Locals often drive quite fast on low-traffic gravel roads; be alert and keep to the right. There are cyclists' maps for many areas.