Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is the world's most prolific religion, with more than 2.38 billion followers, and churches, cathedrals and chapels on every continent including Antarctica. Many of those are on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

While the great majority of religious people in some countries—such as most of Europe, the Americas, Oceania and the Philippines—are at least nominally Christian, Christianity is a minority religion in most of East Asia and the Middle East, while Africa is nearly evenly divided between Muslims and Christians. Christianity has influenced the culture of the countries it is or has been dominant in and has been influenced by pre-existing local cultures, traditions and religions as well, and many important buildings bear witness to the Christian faith of today and bygone eras.

Understand

Christianity is a monotheistic religion, believing in one god. It is an Abrahamic religion, descended from the religion of Abraham who (according to scripture) lived in the second millennium BCE and migrated with his family from Ur of the Chaldees in what is now Iraq to the "Promised Land" of Israel. The other Abrahamic religions are Judaism, Islam, the Baha'i Faith (whose Messiah came in the 19th century) and the now very small Mandaean sect (who believe John the Baptist, not Jesus, was the Messiah).

Christians believe that Jesus of Nazareth was the Messiah (saviour, deliverer) promised to the Jewish people by various prophecies. He is often called Jesus Christ, from the Greek word Χριστός (Christós) which literally means "anointed" but is used to indicate more, in particular to match prophecies that have the Messiah anointed with holy oils.

Christians believe that Jesus was conceived by Mary who was a virgin at the time, that as the Son of God he is the only one who can be considered free from sin in his own right, and that his crucifixion was the sacrifice necessary to cleanse humanity of its sins. According to the Biblical account, Jesus was resurrected after his death on the cross and subsequent burial, and appeared before his disciples. Jesus was then raised to Heaven where he awaits the world's decline into sin and tribulation, after which he will return to Earth and pass the final judgment on humanity.

The vast majority of Christians today also believe in some form of Trinity, which is the belief that God (the Father), Jesus (the Son) and the Holy Spirit are one God in three Persons.

See #Holy Land below for information on visiting the places where Jesus lived and taught.

Disagreements about various points of doctrine, about church administration and power within it, and about the Church's political entanglements engendered a number of schisms, destructive wars, and the large number of Christian denominations in existence today. The most notable denominations are the Orthodox churches, the Roman Catholic church and various Protestant churches.

Christianity's principal religious text, the Bible, comes in many different editions. All versions of the Bible include an Old Testament, which is basically Jewish scripture from before the time of Jesus, and a New Testament which recounts Jesus' life (in the Gospels) and later events. The Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox bibles contain differing numbers of books in their Old Testament, and the translations from ancient to modern languages often differ as well. As in other religions, interpretations of scripture can also differ significantly between different Christian denominations.

Members of the clergy are known as priests in the Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican churches, and as ministers or pastors in most Protestant churches. Friars and monks are not members of the clergy, but are simply men who devote their lives to serving the church, the main difference between the two being that friars work closely with the general community, while monks live secluded lives in cloistered communities and devote their lives to study and meditation. The female equivalent of monks are known as nuns. See Catholic orders below for more.

Early history

Christianity began as a Messianic sect of Judaism, and the early Christians called their houses of prayer synagogues and continued to observe Jewish law, as Jesus and his disciples had. Obstacles to non-Jews converting to Christianity included laws about kosher food and circumcision. After considerable debate, the Church adopted the policy that congregations that did not want to follow these Jewish laws did not have to, because the "New Covenant" of eternal life in Jesus Christ superseded the "Old Covenant" that God made with the Hebrews at Mount Sinai (as detailed in the Biblical book of Exodus).

An important event was the conversion of Saul of Tarsus. This zealous anti-Christian Jew was on his way to Damascus, where he planned to crush the local Christians and stamp out what he saw as a heresy, when he had a vision of Jesus. He then adopted the name Paul and devoted himself to the spread, rather than the annihilation, of Christianity. Paul became one of the leaders of the movement and devoted much time to writing letters (which can be found in Epistles in the New Testament) inspiring the disparate Christian synagogues and maintaining unity. Communities that he sent epistles to included Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Philippi, Colossae and Thessaloniki.

The early church evangelized aggressively and its leaders travelled widely. Some have tombs a long way from home; these have churches built over them and have become pilgrimage destinations.

- Saint Peter. This church is within the Vatican City and the Pope often presides over ceremonies there or in the adjacent St. Peter's Square.

- Saint Paul](https://www.vatican.va/various/basiliche/san_paolo/index_en.html) (Saint Paul's Outside the Walls). This church is just outside the Vatican.

- Saint James (San Diego in Spanish). See the article on the pilgrimage, the Way of St. James.

- Saint Thomas (San Tome Church). This tomb and church are in Chennai, formerly known as Madras. It has a museum. Thomas was martyred on nearby Saint Thomas Mount.<br/>There are still groups in India, mainly Kerala, who call themselves Saint Thomas Christians and claim their roots go back to Thomas. They have interesting churches, some very old. According to their legends, Thomas also sailed on Maritime Silk Road routes to Indonesia and China.

The Roman Empire initially considered Christianity just another of numerous Jewish sects, and Judaism (as the religio licita or allowed religion) was exempt from the requirement to worship the emperor. Once the Romans realized the new religion was more than that (partly because they were preaching to non-Jews) they tried hard, and often brutally, to suppress it; many of the early Christian missionaries including St. Peter were martyred in horrific ways that are often depicted in Christian paintings and other artwork. The most famous site associated with this persecution is the Colosseum where, according to legend, many Christians were thrown to the lions or killed in other crowd-pleasing ways.

Finally, in 313 AD, Emperor Constantine I announced that Christianity would be tolerated, and himself converted to Christianity. According to the traditional narrative, Constantine had a dream in which he saw a cross of light in the sky, and heard a voice telling him to conquer in its name. Following the dream, Constantine marked his soldiers' shields and weapons with crucifixes and won the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, thus convincing him that the Christian God was the one true god. He also called together the Council of Nicea for the Bishops to sort out a consistent doctrine for the whole Church.

Under Constantine's successor, Emperor Theodosius I, Christianity was made the official state religion of Rome, and became mandatory for all Roman subjects. Pagans were oppressed as brutally as the Christians had previously been oppressed. Many pagan temples, including some of the finest buildings of the time, were destroyed. Once Rome was officially Christian, a great temporal power was behind the religion, and this was probably the most important single event in the post-Peter-and-Paul history of the religion.

See #Denominations below for some of the later history, in particular for the schisms that led from the single church of Roman times to the many that exist today.

Festivals

There are many festivals celebrated by Christians, with some even specific to particular sects. However, the two festivals listed below are the most important and celebrated by nearly all Christians, with many otherwise unobservant Christians showing up at church.

- Easter – Celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ after his death on the cross, on a Sunday in March or April. The Friday immediately preceding Easter Sunday is known as Good Friday, and is traditionally said to be the day that Jesus was crucified and died. The holidays begin in the preceding Sunday, when Jesus arrived in Jerusalem, and continues all week (although M–Th mostly are working days). Passions are performed.

- Christmas – Traditionally said to have been the birthday of Jesus, celebrated on 25th December in the Western Christian tradition. People in many countries celebrate by giving each other presents, while in other countries the presents may be given on Saint Nicholas' (Sinterklaas', Santa Claus') Eve in early November or at Epiphany, when the visit of the Magi, who gave the newborn Jesus presents, is celebrated.

The unrelated festival of Saint Stephen (the first Christian martyr) on December 26th is often included in Christmas festivities by local tradition. In many places December 26th is Boxing Day, named for a tradition of preparing boxes for the poor. Stores often have Boxing Day (or even Boxing Week) sales, reducing prices once Christmas is past.

Western churches and the Greek Orthodox Church use the Gregorian calendar (introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582) and celebrate Christmas on December 25th. Most Eastern churches use the Julian calendar (introduced by Julius Caesar) and celebrate on Julian December 25, which is January 7th Gregorian. The Armenian church is in between, using the Gregorian calendar but celebrating Christmas on January 6th.

Some traditions celebrate Advent, several weeks leading up to Christmas, the Twelve Days of Christmas and/or Lent, 40 days leading up to Easter.

Especially in Catholic countries, Carnivale is celebrated as a feast just before the austerity of Lent begins. Wikivoyage has a general article on Carnivale and one on Mardi Gras (French for Fat Tuesday), Carnivale as celebrated in New Orleans. That and the huge Carnivale celebration in Rio de Janeiro are major tourist draws.

The feast of Santo Niño, the Holy Child, is held annually on the third Sunday of January. In parts of the Philippines it is one of the year's most important festivals. In Cebu Province and nearby areas it is known as Sinulog, on Panay Island as Ati-atihan.

There are also many other festivals. In Catholic countries nearly every town and village will have a fiesta on the day of its patron saint. One large one is the feast of John the Baptist, on June 24. Quebec considers Saint-Jean Baptiste their National Day, and for many Quebecois it is a more important holiday than Canada Day on July 1. St. Patrick's Day, on March 17, is widely celebrated in Ireland and by the Irish diaspora. In the US, Canada and Australia, even people with no Irish ancestry often wear green for the occasion and many pubs serve green beer.

Many Christian festivals are at least partly adaptations of older pagan festivals. Winter solstice celebrations in Germanic Europe had yule logs, evergreen trees, mistletoe and holly long before Christian missionaries arrived. Eggs and bunnies were fertility symbols at pagan spring festivities, but now are seen at Easter. Quebec's St. Jean Baptiste has bonfires, as druidic summer solstice celebrations did in pre-Roman Gaul.

Missionaries

Christians have always included many proselytizers, with some of them dedicating their lives to spreading the Gospel, from the Apostles to the present day. Starting in the Roman era they strove to Christianize all of Europe, and by medieval times they had mostly succeeded; the last major holdouts were the Norse people of Scandinavia, who were not fully Christianized until the 12th century. Meanwhile Nestorian Christians were evangelizing much of Asia, reaching Korea by the 7th century.

During the Age of Discovery, the European explorers and colonisers sent missionaries far and wide in order to convert the native peoples, and in many areas were very successful in gaining converts. Along with the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, the Age of Discovery was one of the most important periods that led to the explosive growth of Christianity, eventually resulting in it becoming the world's most prolific religion, a position it maintains today.

In modern times, the missionary work of American Evangelical pastors in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean has led to a massive surge of extreme homophobia.

Buildings

See also: Architecture#Religious buildings

Some main types of Christian buildings and sites are:

- Abbey. A church headed by an abbot/abbess, who is the leader of a community of monks and/or nuns

- Basilica. Either a church built on the rectangular floor plan used in Roman public buildings named basilicas (starting several centuries before Christ), or a church designated as a basilica by the Pope.

- Cathedral. A prominent church, the seat (cathedra) of a bishop

- Church. A building dedicated to religious services, prayer and ceremony.

- Chapel. A small building, or part of a building, set aside for worship. Many chapels are part of a church, set aside either for private worship or as a home for some sacred relic. Many castles include a chapel.

- Monastery. A place where monks live and worship communally

- Convent. A place where nuns live and worship communally

- Cemetery: Can be tied to a Christian congregation or be multi-religious

Many of these are major tourist attractions. Some monasteries and convents offer retreats for interested lay people, some with a strong emphasis on their particular religion but others emphasizing non-denominational quiet and contemplation. See various destination articles and the #Destinations section below for details.

A few Christian denominations use other names for their places of worship; Jehovah's Witnesses have a Kingdom Hall, Quakers or Unitarians a Meeting House, Mormons a temple, and so on.

Denominations

In the first few centuries of Christianity, there were passionate arguments about some key aspects of the faith:

- What is the nature of Jesus? Is He divine, human, some combination of those, or something that transcends both?<br/>If He has both divine and human aspects, how are his two natures related?

- How are Father and Son related? Is the Son a created being or eternal like the Father?<br/

If created, is He then somehow subordinate to the Father?

- Which texts should be considered sacred? In particular, which of the many Gospels then available should be accepted?

Eventually, the church of the Roman Empire mostly settled the question of texts by compiling the New Testament, with only four gospels — Matthew, Mark, Luke and John — becoming part of the canon, while all the other gospels were declared heretical, with the death penalty for possessing them. There was controversy over whether to include the Book of Revelation — the ravings of a madman, divinely inspired, or perhaps both? — but eventually it was accepted as part of the Roman canon.

The other questions were mostly settled at the Council of Nicaea in 325.

Several schisms were to split the church in the years to come, the effects of which can still be felt today in the form of the different denominations of Christianity.

Gnostics

The Gnostics (from Greek γνωστικός, having knowledge) were an influential tendency among both Jews and Christians starting around 100 CE; they emphasized personal knowledge, obtained via meditation and prayer, over scripture and church teachings.

The Gnostics were heavily persecuted by the Church of the Roman Empire and the movement mostly died out within a few centuries. However, they did have a considerable influence on the Oriental Orthodox churches, especially the Coptic Church. They had many documents, including several Gospels, which they considered sacred but which the Church refused to include in the Bible and declared heretical.

- Coptic Museum, Cairo, Egypt. Houses the Nag Hammadi Library, the largest collection of re-discovered Gnostic Gospels. They were found in the town of Nag Hammadi (near Luxor) in 1945. Some Gnostic stories, while not included in the Biblical canon, are in the Qur'an, the holy book for Muslims.

The Trinity

The doctrine of the Trinity — the belief that Jesus (the Son), God (the Father) and the Holy Spirit are one God in three Persons — is not stated explicitly anywhere in the Bible, though some theologians have trinitarian interpretations of various passages in both Testaments. The doctrine was not stated in fully-developed form until the 3rd century CE, and not definitively labelled as orthodox teaching until early in the 4th.

The First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE excommunicated the prominent non-trinitarian Arius, declaring his teachings (the Son is a created being, not eternal, and subordinate to the Father) heretical, and agreed on an important document.

- Nicene Creed. A statement of common beliefs which anyone must accept to be considered a Christian, including the divinity of Jesus, the Trinity, the virgin birth, the resurrection and His eventual return to judge humanity. This creed declared an orthodoxy that nearly all bishops could accept, resolving the thorny problems mentioned above.

All the major Christian denominations today — Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant — accept the Nicene Creed as a fundamental part of their doctrine, and many recite or sing it as part of their liturgy.

Islam honours Jesus as a prophet and the Messiah, and reveres many Old Testament prophets as well. However, they do not consider Jesus divine. To them, there is one God, indivisible, and the ideas of worshipping Jesus or of the Trinity are completely unacceptable.

Non-trinitarians

Today there are few non-trinitarian Christians. The Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses are mentioned below. Other non-trintarian groups are:

Today there are few non-trinitarian Christians. The Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses are mentioned below. Other non-trintarian groups are:

- Unitarians. This group began in Europe in the 16th century and today is moderately widespread in North America and parts of Europe, with a few congregations elsewhere. There are no great Unitarian cathedrals to visit, but many of their meeting houses are lovely and several are fine examples of modern architecture.

- Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ). This church was founded in the Philippines in 1914 and today has several thousand congregations and a few million members, nearly all in that country. They claim to be restoring the original church, as Christ taught, and are non-trinitarian. Except for a few larger ones, their churches all look exactly identical.

- Pentecostal Missionary Church of Christ (4th Watch). A church founded in the Philippines in the 1970s, with about 800,000 members as of 2020. They are very active evangelists; they produce both radio and TV programs.

Nestorians

Nestorius was Archbishop of Constantinople until the other bishops condemned some of his teachings as heretical at the Council of Ephesus in 431 and removed him from his post. Today Ephesus is a major archaeological site and one of Turkey's main tourist attractions. He retired to his home monastery near Antioch, and was later exiled to Egypt. At the time, Antioch was one of the main cities of Syria and a major center of Christianity; today it is Antakya in Turkey.

Nestorius taught that the human and divine aspects of Christ were two distinct natures, not unified. His interpretation of Christianity lived on in the Church of the East which never accepted his condemnation by the western bishops. That church was based in Persia and had the support of the Persian Empire, likely mainly for political reasons; the Persians did not want a church with strong ties to either Byzantium or Rome becoming too influential in their territory.

The Church of the East sent missionaries east along the Silk Road, reaching China and Korea hundreds of years ahead of other Christians. Xi'an, China has a Nestorian stele (stone monument) from the 7th century, and outside town the Daqin pagoda, a Nestorian church that was built in 635 and was converted to a Buddhist monastery and shrine after the Nestorians died out locally. Marco Polo mentions communities of Nestorian Christians in Samarkand, Kashgar, Yarkand, Yunnan and Tangut, and Nestorian missionaries among the Mongols, in the 13th century.

Today, the church, now known as the Assyrian Church of the East, still exists but it has not had government support in centuries and is now much smaller than in its heyday. What was once known as Persia is now called Iran and is almost entirely Muslim, though the Assyrian Church of the East has been officially recognised as a minority religion and is guaranteed representation in the country's legislature.

Nestorian churches do not place an emphasis on iconography, and tend to be simple and plain, much like later Protestant churches, though they are not explicitly iconoclastic.

Oriental Orthodox churches

.jpg/440px-2014_Prowincja_Kotajk,_Klasztor_Geghard_(02).jpg) See also: Churches in Ethiopia

See also: Churches in Ethiopia

Some of the earliest Christian churches included the Syriac church, centered in Antioch, which is now in Turkey; the Coptic church of Egypt and Ethiopia, and the Armenian Apostolic church.

After the Council of Chalcedon in 451, these churches disagreed with the council and broke off. The church in Georgia joined them briefly, but later returned to the main Orthodox fold. The main theological dispute was on whether the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ are two different aspects of one nature (Oriental Orthodoxy), or two separate but unified natures (Chalcedonean Christianity).

There are splendid ancient churches and monasteries, some of them still active, in Ethiopia, Armenia and Georgia.

The Coptic Church claims to have been founded by Saint Mark the Apostle in 42 AD, and therefore to be the world's oldest Christian denomination. The Coptic liturgy is celebrated in the even older Coptic language. There is a very historic district known as Coptic Cairo with a museum and several fine old churches.

Some of these churches still require their followers to adhere to certain aspects of Jewish law; the Ethiopian and Eritrean churches prohibit consumption of pork, while both churches, as well as the Coptic Church, practise ritual purification, require their male followers to be circumcised, and observe both the Jewish and Christian sabbaths.

The Great Schism

The Great Schism split Chalcedonian Christianity into two great branches:

- Roman Catholic Church, NA°, NA°. This is very much the largest Christian denomination today, partly due to extensive missionary activity beginning in Roman times and peaking during the Age of Discovery; around 1.3 billion of the world's 2.4 billion Christians are Catholic.

- Eastern Orthodox churches, NA°, NA°. These originally included the Russian, Greek, Georgian, Serbian, Bulgarian and Romanian churches. In 2018, the Ukrainian Church was recognized as a member in its own right, rather than part of the Russian Church, and the Russian Church left in protest. The split was partly a result of the Roman Empire being divided into the Western Roman Empire with its capital in Rome, and the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) with its capital in Constantinople; each empire supported a different Church (and the Persians supported the Nestorians).

An important doctrinal dispute was over the role of the Pope. To Roman Catholics he is pontifex maximus (the greatest priest) and the undisputed head of the Church. To Orthodox Christians he is just the Bishop of Rome and has no authority outside his See; in particular he does not rule over other bishops, and at most could be considered primus inter pares (first among equals). Today the Archbishop of Rome, also known as the Pope, remains the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, while the Archbishop of Constantinople (today's Istanbul), also known as the Ecumenical Patriarch, remains the symbolic leader of the Eastern Orthodox churches.

The split was a rather gradual affair with controversy from the 4th century on; it became final in 1050 when each side excommunicated many of the other side's bishops. It became rather messy during the Crusades when large numbers of heavily armed Roman Catholics entered Orthodox territory. At times the two groups co-operated to attack the Muslims, but they also fought each other. Some historians contend that the Crusaders killed more Orthodox and Coptic Christians than they did Muslims, and it is often argued that the Crusaders' actions directly contributed to the Byzantine Empire's decline and final conquest by the Ottoman Turks almost 200 years later.

The geographic division between east and west remains roughly the same as it's been for centuries, though it is not quite a neat one. Some very longstanding Eastern Rite communities, most notably in Western Ukraine and among the Arab Christians of the Middle East and North Africa recognize the Pope as their leader and are therefore Catholic; they are referred to as the Eastern Catholic churches. There are also localized Eastern Orthodox congregations in some mainly Roman Catholic areas of Europe, dating back hundreds of years, and some more recent ones. There is for example quite a nice Russian Orthodox church in Dresden complete with icons and Moscow-style church spires; while it was built in the 19th century, it must have made some Soviet soldiers very homesick during the Cold War. These congregations have almost always been established to serve the needs of specific immigrant ethnic communities (so that a major western city such as London or New York City might have separate Greek, Serbian, and Romanian churches).

Cathars

Starting in the 11th century, the Cathars, also known as the "Albigensian Heresy", gained many adherents, especially in Languedoc which is now in the South of France; the department of Aude calls itself "Cathar Country" today. There were also Cathars in Northern Italy. The movement was heavily influenced by Manichaean Gnosticism.

- Albigensian Crusade. The Catholic Church considered the Cathars a threat and the King of France backed the Church, apparently mainly as an excuse to add Languedoc to his realm. They ordered a crusade against the Cathars and slaughtered tens of thousands of them.

- Toulouse. This city was the capital of the region and a center of Catharism. A Papal Legate was assassinated in 1208 while returning to Rome after excommunicating the Count of Toulouse for being too gentle with the Cathars, and the Crusade was the Church's response to the assassination. The city changed hands several times during the Crusade, and various Counts of Toulouse were Cathar leaders.

Today Toulouse is the fourth largest city in France and a major tourist destination. 2023-01-05 - Albi. This small town is the capital of the department of Tarn. The crusade was named after it, possibly because it was the seat of a Cathar Bishop. Centuries later it was the birthplace of the painter Toulouse-Lautrec, and today its main tourist attraction is a museum with a fine collection of his work.

- Béziers. This town was taken in 1209, early in the Crusade, and much of the population massacred. By some accounts, when the Papal Legate in charge was asked how to distinguish Cathars (who should be killed) from Catholics (who should not) he replied "Kill them all; God will know His own."

- Carcassonne. This city surrendered shortly after Béziers; many Cathars were driven from the town, naked by some accounts but "in their shifts and breeches" by others. Later the Cathars took the city back and the crusaders re-took it.</br>Most of the medieval city, including the city wall, still stands and today it is a popular tourist destination.

- Montségur. This castle in the mountains of Ariège near the Spanish border was the last Cathar stronghold to fall, in 1243. Afterward over 200 Cathars who refused to recant their faith were burned alive.

- Museum of Catharism. This museum is in Mazamet where some Cathars took refuge, up in the mountains of Tarn. The fighting lasted over 30 years; but by 1245 France and the Church had achieved a complete victory in the field. However, it was not until about 1350 that Catharism was entirely wiped out.

The Church created two other institutions, both initially in Toulouse, to help put down the Cathars.

The Dominican Order of friars were preachers sent out to spread the Gospel and to counter heresy. Like the Cathars — and unlike the corrupt churchmen that the Cathars had heaped scorn on — they lived simply and often preached to the poor.

The Dominican Order of friars were preachers sent out to spread the Gospel and to counter heresy. Like the Cathars — and unlike the corrupt churchmen that the Cathars had heaped scorn on — they lived simply and often preached to the poor.

- Notre-Dame-de-Prouille Monastery, 43.1878°, 2.0344°. Saint Dominic was given land in the village of Prouille, just outside Toulouse. The first building was a residence for Cathar women who had recanted; it soon became a convent for Dominican nuns. Later there was also a monastery for the monks. Both were destroyed during the French Revolution, but they were rebuilt and both are still in use today. The Inquisition was created to root out heresy, in particular the remaining Cathars. It took about 100 years for the remaining Cathars to be annihilated. Inquisitions — against Jews and Muslims after the 1492 Reconquista of Spain from the Moors, against witches, and later against Protestants — continued until some ways into the 19th century.

In the early days of the Inquisition most of its judges were Dominican friars.

Protestants

Western Christianity was much disrupted during the Protestant Reformation when several groups split off from the Roman Catholic Church. As with the Cathars, a major issue was corruption in the Catholic Church. Today there are dozens of Protestant denominations, most of which can trace their doctrines back to one or both of the great 16th century reformers, the German Martin Luther and the French John Calvin.

One important difference between Catholic or Orthodox churches and many Protestant churches is that while Orthodox Christians and Catholics venerate icons of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and saints, many Protestant churches are iconoclastic (rejecting the use of icons and in some cases in the past, outright destroying them), with simple churches that are not ornate and feature just a symbolic cross, rather than a crucifix showing the Body of Christ. Protestant churches that do use icons to some degree and sometimes have elaborate architectural decorations include Anglican and Lutheran churches, though the Anglican church also went through an iconoclastic period, during which they destroyed most English Catholic sculptures and paintings.

Hussites

The first successful schism in Roman Catholic Europe was the one led by the theologian Jan Hus (1369–1415), rector of the University of Prague. The reasons for the split were complicated but Hus is generally described as motivated by a desire to reform and renew the Catholic Church. He was burnt at the stake in Konstanz for alleged heresy. The location of the burning is now marked with a monument, and there is a museum called Hus Haus in the city's old town. A Jan Hus Memorial is prominently positioned in Prague.

From Hus' death on, there were a series of Hussite rebellions against the Catholic Habsburg rulers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire who tried to apply the doctrine of Cuius regio, eius religio, the religion of the ruler dictates the religion of those ruled. There were five Roman Catholic Crusades which the Hussites resisted successfully.

- Defenestration of 1618. A group of officials delivered a stern message from the Catholic King to the mainly Hussite Estates (parliament). Two were told to leave and the other three, all Catholic hard-liners, were hurled from a window of Prague Castle, 21 meters (70 feet) up. They all survived, some writers claiming by miraculous intervention and others saying because they landed in a dung heap. This defenestration was one of the main incidents precipitating the Thirty Years' War, a very destructive conflict that lasted until 1648 and eventually involved most of Europe.

During the time period of that war, the main Hussite church was the Moravian Brethren; it was heavily persecuted and largely driven underground in its native Bohemia, but Moravian ideas spread considerably as many church members became refugees in other Protestant regions.

- Comenius. This Moravian Bishop is considered the main inventor of modern education methods. He advocated such then-radical things as universal education — educating the lower classes and even girls, not just the sons of the nobility and novice monks — and using the local language, not just Latin. On a practical level, he helped both Sweden and Britain re-organize their school systems. There is a university named after him in Prague.

The Hussite Church still exists, although the present-day population of the Czech Republic is majority Roman Catholic (though largely secular).

Today the Moravian Church is the main religious movement claiming Hussite ancestry; it has over a thousand congregations in many countries, and about 1.1 million members. Moravian churches can be found throughout the Caribbean with their lamb imagery and the words "our lamb has conquered; let us follow him" (Latin: Vicit agnus noster, eum sequamur) very recognizable in places like Bluefields, Nicaragua. The German name of the Moravian church is Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine (sic!) after their center in the Saxon town of Herrnhut. There is a Moravian University in Pennsylvania.

Lutherans

See also: Protestant Reformation#Martin Luther

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was the first of the great leaders of the Protestant Reformation. As with the Cathars and Hussites, a major issue was corruption in the Catholic Church; in particular Luther objected to the sale of indulgences, putting a price on forgiveness of sin.

There were also disagreements regarding the interpretation of scripture, such as whether only faith in Jesus Christ is needed for a place in Heaven after death (Luther) or good works are also required (Catholicism) and whether it is necessary to obey the Pope and Catholic Church hierarchy or more important for each Christian to read and understand the Bible individually.

Luther translated the Bible into German to let more people read it, in defiance of Church rules that allowed only Greek or Latin editions. His translation was widely distributed due to the recent invention of the printing press, and is still used.

- Ninety-five Theses. Luther's declaration of rebellion was mailing this document to the local Archbishop. Some accounts have him also nailing it to a church door in Wittenberg where he was a professor of theology; certainly it was reprinted and widely circulated. It dealt mainly with forgiveness of sin, with Luther holding that only sincere repentance was required, the Church's tradition of confession was not essential, and sale of indulgences was nonsense. The town has Luther memorials which are now a .

- Diet of Worms. This was a conference called by the Holy Roman Emperor (see Austro-Hungarian Empire) in 1521 in the city of Worms (pronounced approximately verms) at which Luther gave a famous speech refusing to recant. After it, the Emperor promulgated the Edict of Worms declaring him a heretic. The town has a monument to Luther.

Luther's followers were known as the Lutherans, and many modern Protestant denominations can trace their roots to this movement. The Lutheran Reformation in Germany removed the organisational hierarchy, but in the Nordic countries it was carried over and bishoprics have been retained.

Luther was a well-known and beloved lutenist and composer who appreciated artistic beauty and decoration, and Lutheranism is not an iconoclastic sect, so while Lutheran churches may not be as ornately adorned as Catholic and Orthodox ones, there are often decorations on and in the buildings.

Calvinists

See also: Protestant Reformation#Switzerland

Subsequently, Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) and John Calvin (1509–1564) led a truly iconoclastic and severe branch of the Reformation that inspired the Dutch Reformed Church, the French Protestants (Huguenots), English Puritans, the Congregationalists, and Presbyterian polities such as the Church of Scotland.

Calvinist churches are generally quite plain, emphasizing symmetry and clarity of form and eschewing all but the simplest ornaments.

Many of the early colonies in what is now the United States, especially in New England, were founded by Puritans (English Calvinists) fleeing persecution in Britain. See Early United States history#Timeline for some of the details. Other Calvinist groups also spread to the colonies; the Congregationalists began in England and the Presbyterians in Scotland, but both exist today in all the countries where British colonists settled. The Dutch Reformed Church is strong in South Africa.

While the French Huguenots began as a powerful group, they were defeated after decades of on-and-off wars, and after Louis XIV formally stripped them of legal protection from state persecution in 1685, many of them were faced with an ultimatum: Convert, die or emigrate. Many chose the latter and many German princes, especially the House of Hohenzollern that ruled Brandenburg and parts of Franconia accepted the refugees and even built entire neighborhoods for them, which is still very evident in cities like Erlangen. Others found refuge in other parts of Europe and some went outside Europe; for example, a neighborhood of Staten Island, New York is named Huguenot, there is a Franschhoek ("French Corner") in South Africa and a "France Antarctique" colony in Rio de Janeiro. Some were able to stay in France; their descendants are a significant minority in parts of Provence today. The French state has since apologized and officially extended an invitation towards all descendants of Huguenot refugees to return to France, similar to what Spain and Portugal did for the descendants of expelled Sephardic Jews.

Anabaptists

This was an evangelical movement that originated in German-speaking parts of Europe. The part of their doctrine that gives them their name is insistence that baptism should be reserved for adults who have professed belief in Christ. Modern denominations with Anabaptist roots are the Amish and Mennonites, the Quakers, and the Hutterites.

They were among the most radical Protestants; both Luther and Calvin rejected their teachings. Both Catholic and Protestant churches persecuted them.

- Jakob Hutter, c.1500-1536. The founder of the Hutterites was burned at the stake in Innsbruck, in front of the Golden Roof. There is a commemorative plaque at the site. Today they are found mainly in the U.S. and elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere where many fled to avoid the persecutions. In particular, there are many in Pennsylvania. King Charles II had a huge debt to the Penn family and, to avoid having to find the cash, gave William Penn an enormous estate in the New World; later that estate would become the US state of Pennsylvania. Since Penn was a Quaker himself, and a vociferous advocate of religious freedom, he welcomed Anabaptist immigrants.

Some things common among Anabaptists — such as faith healing, speaking in tongues, and the emphasis on the importance of the experience of being saved — are also found among later evangelical movements.

Evangelical Christianity

Evangelical Christianity is a fundamentalist Protestant movement, most prominent in the United States, that emphasizes strict Biblical literalism, aggressive proselytizing and the centrality of the "born-again" religious conversion experience.

- Baptists. The Baptist church arose in Holland and England in the 17th century. They were influenced by the Anabaptists who had peaked in the 16th century, but are a distinct movement. Today they are a major denomination, especially in the American South. Baptists perform their baptism by full immersion in water, and like the Anabaptists believe that baptism should only be performed on professing adults.

- Pentecostals. This movement traces its origin to radical Evangelical revival movements in the United Kingdom and the United States in the late 19th century, becoming most established in the latter, where it would play an important role in the charismatic movement. Their doctrine emphasizes having a personal relationship with God through baptism in the Holy Spirit.

In addition to the aforementioned branches, many Evangelical churches claim to be non-denominational.

Evangelicals are hugely influential in American politics, with right-wing politicians often citing the Bible in order to justify their policy positions. Since the advent of television in the mid 20th century, televangelism has become a big money industry in the United States with numerous celebrity pastors, and a large number of Evangelical television channels and radio stations to serve its large Christian population.

Depending on which church you go to, some theological concepts you may encounter in an Evangelical church include the prosperity gospel, which teaches that financial wealth is God's reward for one's devotion and financial contributions to the church, and faith healing, in which medical interventions are eschewed in favor of prayer. Many Evangelical churches also practice speaking in tongues during their services, which often sounds like gibberish to outside observers, but is said by believers to be a secret language that only God can understand. Many Evangelical churches also belong to the charismatic movement, with congregation sizes numbering in the thousands, and services that resemble rock and pop concerts, thus leading a popular resurgence of Christianity among many youths.

Evangelical Christians also believe that it is their sacred duty to bring about the apocalypse by fulfilling the prophecies in the book of Revelation, and since an ingathering of Jewish exiles into the Land of Israel and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem are among the central prophecies, many Evangelicals are among the world's staunchest Zionists.

This form of Christianity has been very successfully exported to much of Latin America, the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as numerous parts of Asia such as South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore, and is also quite influential in other English-speaking countries like the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, particularly among immigrant communities. The influence of American-inspired Evangelical megachurches is particularly evident in historically Buddhist South Korea, which boasts 11 of the world's 12 largest Christian congregations, and sends more Evangelical Christian missionaries abroad than any other country except the United States.

The main non-Anglophone European Evangelical Lutheran churches are very different from these movements.

Church of England

The Anglican Church (known in the U.S. as the Episcopal Church to avoid references to the British monarchy) was formed when the Church of England split from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534, due to King Henry VIII wanting to get a divorce, which is not allowed under Roman Catholic doctrine.

The Anglican Church (known in the U.S. as the Episcopal Church to avoid references to the British monarchy) was formed when the Church of England split from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534, due to King Henry VIII wanting to get a divorce, which is not allowed under Roman Catholic doctrine.

Although considered by many to be a Protestant denomination, it does not share the same Lutheran or Calvinist origins as other Protestant churches, and is in many ways closer to the Catholic and Orthodox churches in doctrine and structure. It is therefore considered by some people to be a completely separate branch from Protestantism. The Anglican Church, like the Catholic, Orthodox and to some extent Lutheran churches, may use icons, and many of its rites continue to be similar to Catholic and Orthodox rites, as does the structure of its liturgical year. Almost unique among Protestant denominations is Anglicanism's partial rehabilitation (by some Anglicans and not others, at least) of the Catholic and Orthodox cult of relics and shrines, which can be seen at certain pilgrimage sites such as Walsingham in Norfolk.

There is a large range of variation between Anglican congregations; some are "high church", quite close to Catholic in style, while others are "low church", almost Calvinist. This variation is tolerated, sometimes even encouraged, by the church hierarchy, and clergy are allowed to exercise a great degree of latitude in their interpretation of Anglicanism's fundamental statement of doctrine, the 39 Articles of Religion.

The head of this church is nominally the British monarch, but the Archbishop of Canterbury is the leading churchman.

In the 18th century, John Wesley led a reform movement within the Church of England, influenced by Moravian (Hussite) doctrines. After his death, this evolved into a separate Methodist church.

New American churches

The United States is mostly Protestant, including many Evangelicals, with substantial contingents of Roman Catholics and Episcopalians (known as Anglicans elsewhere), and some Orthodox Christians.

It has also been a breeding ground for new Christian movements whose teachings deviate significantly from mainstream Christianity. Those listed below remain popular to this day. Others, such as the Shakers, have virtually died out (but see Touring Shaker country) and some, such as the Christian Scientists, have been greatly reduced in size.

- Mormons (LDS Church). The Mormons or Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are a non-trinitarian sect who believe that Jesus incarnated in North America and preached to the Indians after he was done in Palestine. They have a third testament, the Book of Mormon, describing that ministry. They are forbidden from consuming alcohol, coffee or tea.<br/>The movement began in the Eastern US, but the early Mormons were persecuted there; many Christians considered them heretics or thought some of their customs, such as polygamy, were sinful. Starting in 1846, many Mormons went west along the Oregon Trail; most settled in Utah, especially around Salt Lake City, and the state continues to have a Mormon majority to this day. Many of the early settlers in what is now Grand Teton National Park were Mormons and today's tourist sights include some historic Mormon ranches.<br/>You can often see a statue of a person blowing a trumpet on top of the highest spire of Mormon temples; this represents the angel Moroni, who is said to have guarded the golden plates that were the source material for the Book of Mormon before presenting them to the church founder, Joseph Smith.

- Seventh-day Adventists. This group believe the Apocalypse, and the Advent or Second Coming of Jesus, will come soon. Much of their doctrine is similar to that of the Evangelicals or other Protestants. However, unlike most Christians, their sabbath is Saturday (the 7th day, the same day as the Jewish Sabbath) and they follow a version of the Jewish kashrut dietary laws. They are also strongly pacifist, and forbidden from carrying weapons.

- Jehovah's Witnesses. This is a non-trinitarian sect who believe the apocalypse is coming soon. They evangelize a lot, often handing out literature on the street or going door-to-door. They do not accept blood transfusions, as they consider this to be in violation of the Biblical prohibition against drinking blood. They also do not vote, work for the government, sing national anthems or salute national flags, as they believe that their allegiance should lie with God and God alone. In addition, they do not celebrate many festivals that other Christians celebrate such as Christmas and Easter, as they believe that these festivals have their roots in paganism and are thus not truly Christian. The name Jehovah is a corruption of YHWH, the name of God as revealed to Moses in the Book of Exodus, and Jehovah's Witnesses invariably refer to God using this name. These churches have been heavily involved in missionary activity. For example, all three mentioned above now have many congregations in the Philippines.

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

Possibly the strangest offshoot of Christianity was the Taiping movement in 19th-century China. Their founder Hong Xiuquan claimed to be Jesus' younger brother and to regularly visit Heaven for chats with the family.

Their rebellion against the Qing Dynasty was the bloodiest civil war in history, killing far more than the American Civil War which was fought at about the same time with better weapons. They controlled about a third of China for over a decade. There is a museum in Nanjing, which was their capital. The rebellion was eventually crushed by the Qing Dynasty, with some help from Western powers and a lot from foreign mercenaries.

A historical novel with an account of some of this is Flashman and the Dragon.

Destinations

See also: Christmas and New Year travel

Holy Land

The Holy Land today is divided between Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian territories.

- Jerusalem, Israel 📍. The holiest city in the religion, site of Jesus' crucifixion and also a holy city for Judaism and Islam. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands on the site where Jesus was said to have been buried and resurrected.

- Bethlehem, West Bank 📍. The birthplace of Jesus according to the New Testament. The Church of the Nativity stands on the site where Jesus was said to have been born.

- Nazareth, Israel 📍. The hometown of Jesus' family, and believed by many historians to be his actual historical birthplace; he was sometimes called "Jesus of Nazareth". Today one of the centers of the Arab Christian minority in Israel, that - unlike many other Christian minorities in the Middle East - continues to grow and thrive.

According to the Bible, it was here that the archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary and announced that she would bear the Son of God, an event known as the Annunciation. The precise location of the Annunciation is a subject of dispute between different Christian denominations; the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation sits on top of a spring where Mary was said to have been drawing water when the Annunciation happened in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, and the Basilica of the Annunciation sits on top of a cave said to be Mary's home and the site of the Annunciation in the Roman Catholic tradition.

- Tel Megiddo, Israel. An archeological site that was once an important Canaanite city-state, and later part of the Kingdom of Israel. According to the Book of Revelation, there will be a great battle between several armies at the site that will herald the beginning of the apocalypse. Today, it is a popular pilgrimage site for Evangelical Christians. The English word "Armageddon" was derived from the name of this site.

- [Al-Maghtas, Jordan](http://www.baptismsite.com/)[ 📍](https://www.google.com/maps?ll=31.837109,35.550301&q=31.837109,35.550301&hl=en&t=m&z=11). The site where Jesus was said to have been baptised by John the Baptist.

Wikivoyage has links to some of the most important places of Jesus' life at Christian Holy Land and an itinerary for visiting many of them at The Jesus Trail.

Headquarters

Some places are of interest because they are the main centers of various Christian groups:

- Vatican City 📍. An independent state within Rome, center of the Catholic Church and home to St Peter's Basilica and the Sistine Chapel. The Vatican territory in Rome also officialy includes the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran, the Pope's cathedral in his role as Bishop of Rome, the Basilica of St. Mary Major and the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls.

- Istanbul, Turkey 📍. Formerly Constantinople and is the home of the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Churches, with his cathedral being the Church of St George in the Fener district. Scattered over a wider area in the old city, the former cathedral churches include Hagia Irene, Hagia Sophia, the Church of Holy Apostles, and Pammakaristos Church, all of which serve as mosques or museums today (except the Holy Apostles, which was replaced by the Fatih Mosque on the same site), and contain a variety of Eastern Orthodox (Byzantine) art.

- Avignon 📍 A series of Popes ruled here 1309–1376. From 1378 to 1417 there were two men claiming to be Pope, one in Rome and another in Avignon. All of the Avignon Popes were Frenchmen and under the influence of the French kings.

Today Avignon is a popular tourist destination and the medieval town center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The imposing Palais des Papes and the nearby cathedral are among the main sights. One of the wine of the Rhone Valley (the region around Avignon) is Chateau Neuf du Pape, which translates to "the Pope's new house". This is one of the great wines of France, definitely worth trying if you like wine and are in the area. The red Chateau Neuf is better known, but there are also some lovely whites.

- Moscow, Russia 📍. The Danilov Monastery, on the west bank of the Moskva River, is the administrative center and official residence of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour close to the Kremlin is the Patriarch's cathedral in his role as Bishop of Moscow. The cathedrals inside the Kremlin, though no longer active, are historically and spiritually significant, as well as the famous multi-domed St. Basil's which, contrary to popular thought, is neither a cathedral nor inside the Kremlin.

- Sergiev Posad, Russia. 70 km northeast of Moscow, the venerable Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius monastery, founded in 1337, is the Russian Orthodox spiritual headquarters since imperial times.

- Cairo, Egypt 📍. Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Abbassia is the current seat of the Coptic Pope, the leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the symbolic spiritual leader of the Oriental Orthodox communion. The Church and Monastery of St. George in the Coptic Cairo neighbourhood is the current seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria.

- Alexandria, Egypt 📍. Home to Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral, the historical seat of the Coptic Pope.

- Echmiadzin, Armenia 📍. The Echmiadzin Cathedral is the seat of the Armenian Catholicos, head of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

- Mtskheta, Georgia 📍. The seat of the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia, head of the Georgian Orthodox Church.

- Damascus, Syria 📍. The Cathedral of Saint George in Bab Tuma (the old city) is the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church, an Oriental Orthodox church which started in 512, although it claims succession from St Peter of Antioch, and therefore is ceremonially known as the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East. Former seats of the church include the Monastery of Saint Ananias (Deyrulzafaran) near Mardin, and Saint Mary Church in Homs. Damascus is also the seat of the Antiochian Orthodox Church, an autocephalus Greek Orthodox church within the communion of Eastern Orthodoxy; its cathedral is the Maryamiyya Church on Straight Street (of the New Testament significance).

- Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 📍. The seat of the Abuna, head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

- Erbil, Iraq 📍. Home to the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, the seat of the Catholicos-Patriarch, the leader of the Assyrian Church of the East, which reverted to Eastern Christianity (see above) after splitting off from the (Eastern-rite) Chaldean Catholic Church.

- Canterbury, United Kingdom 📍. Home to the Canterbury Cathedral, the church of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is the spiritual leader of the Anglican Church.

- Salt Lake City, Utah, United States 📍. Center of the Latter Day Saints (Mormon) movement. Notable Mormon sites include the Salt Lake City temple at Temple Square, as well as the Salt Lake City Tabernacle, the home of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Non-Mormons are not permitted to enter the temples, and even Mormons may have to prove that they are members in good standing before entering. However, travellers are welcome to look around the outside.

- Silver Spring, Maryland, United States 📍. Home to the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, the headquarters of that church.

Pilgrimages

There are various places of pilgrimage around the world that traditionally get visited Christian pilgrims, although pilgrimage is not a central part of the religion; most Christians never do any pilgrimage. The age-old way to perform a pilgrimage was on foot or on the back of a horse or donkey.

Several pilgrimages are related to the Virgin Mary:

- Lourdes, France 📍. The world's best-known center of Marian pilgrimage. Its springs are thought to have healing powers.

- The pilgrimage on foot to Fátima 📍, in Portugal, ending at the Chapel of the Apparitions. This commemorates the apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary reported by three little shepherds – Lúcia, Francisco and Jacinta – in 1917.

- Međugorje, Bosnia and Herzegovina has been a major site of pilgrimage following claims of visions of the Virgin Mary.

- The Via Maria is a series of hiking and pilgrimage routes marking a large cross over the map of the formerly Austro-Hungarian lands, connecting the Marian shrines scattered across the area. Other famous pilgrimages include:

- The Way of Saint James, ending at the splendid Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, has been an important Catholic pilgrimage route since the Middle Ages.

- The walk along the Via Dolorosa, the street in Jerusalem on which Jesus is said to have carried his cross, ending at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

- Saint Olaf's Way to Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Norway, where St. Olaf is buried.

- The Jesus Trail is a 65-km (40 mile) walk through Galilee that visits many places where Jesus also walked.

- The Saint Paul Trail is a 500-km hiking trail partly following the footsteps of Paul the Apostle on his first missionary journey across Asia Minor. It will become part of the Via Eurasia, envisioned to connect various pilgrimage and cultural routes from Rome to the early Christian sites on the Turkish Mediterranean.

However, there are many other places of pilgrimage, and most of them are usually no longer approached by taking a long trek. For example, most long-distance travellers to The Vatican arrive by plane to Rome's Leonardo da Vinci-Fiumicino Airport.

Several lesser known places also venerate the apparition of Mary or the supposed remains of some saint, especially in Orthodox and Catholic countries. As Melanchton, a 16th century ally of Martin Luther, famously quipped "Fourteen of our twelve apostles are buried in Germany". Oftentimes those religious sites and objects have been a major draw for travellers for centuries and thus (former) "tourism infrastructure" may be an attraction all by itself.

Catholic orders

The Roman Catholic church has a number of religious orders, groups of people who are part of a community of consecrated life, and are often heavily involved in missionary work and charitable causes. Orthodox and Anglican churches have similar orders and some Protestant denominations have missionary societies where people dedicate their lives to spreading the Gospel and other good works.

Many of these orders have impressive churches, monasteries and convents that tourists might want to visit. Some of these groups have also founded various schools and universities around the world, some of which are still very prestigious and known for providing high-quality education. These schools and universities often have impressive historical buildings on their campuses, which can sometimes be visited by tourists, though you may be required to join a guided tour to do so.

- Augustinians (Order of Saint Augustine). Founded in 1244 by bringing together several groups of hermits following the Rule of Saint Augustine in the Tuscany region of Italy. This set of rules was written by St. Augustine of Hippo in 5th century, and emphasised chastity, poverty, obedience, charity and detachment from the world, among others. The Augustinians have been very active in promoting education over the years, having founded numerous schools worldwide. They are perhaps most famous for the monk Gregor Mendel, who was the abbot of the St Thomas's Abbey in Brno, Czech Republic, and whose experiments on peas formed the basis of modern genetics. Their mother church is the Basilica of St. Augustine in Rome, Italy.

- Benedictines (Order of Saint Benedict). A monastic order founded by St. Benedict of Nursia at the Abbey of Saint Scholastica in Subiaco, Italy in A.D. 529. The are often called the "black monks" because of their practice of dressing in black, and are expected to adhere to a strict communal timetable. They are also known for having played a key role in the development and promotions of spas. Their mother church is the Sant'Anselmo all'Aventino in Rome, Italy.

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers). Founded in 1216, originally as an order of nuns, by St. Dominic of Caleruega in the Notre-Dame-de-Prouille Monastery in Prouille (just outside Toulouse, France) as a counter-movement to the Cathars. The Dominicans live a frugal lifestyle and place a strong emphasis on education and charity. Their mother church is the Basilica of Saint Sabina in Rome, Italy.

- Franciscans (Order of Friars Minor). Founded by St. Francis of Assisi in 1209, with an emphasis of living a life of austerity. Its mother church is the Porziuncola in Assisi, Italy, while its founder is entombed in the impressive Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi in the same city. A related order is the Order of St. Clare, also known as the Poor Clares, an order of nuns founded by St. Clare of Assisi, one of St. Francis' followers. St. Clare is entombed in the Basilica di Santa Chiara in Assisi.

- Hieronymites (Order of Saint Jerome). A cloistered order founded in Toledo, Spain in the late 14th century with the aim of emulating the life of the 5th-century Biblical scholar, St. Jerome. Its headquarters today are in the Monastery of Santa María del Parral in Segovia, Spain. Another famous Hieronymite monastery is the Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon, Portugal, in which the pastel de nata (Portuguese custard tart) was invented by its monks, and the most famous bakery selling this pastry is the nearby Pastéis de Belém.

- Jesuits (Society of Jesus). This order was founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola and six other companions, including the famed St. Francis Xavier, in the crypt of the Saint-Pierre de Montmartre in Paris, France in 1540. Their mother church today is the Church of the Gesù in Rome, Italy, in which St. Ignatius is entombed. Another important church is the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Goa, India, in which St. Francis Xavier is entombed.

The order is famous for its charitable and teaching work; the Jesuits founded numerous schools around the world, and for much of their history have played a major role in providing education to the poor. They are also known for scholarship and for prowess in debate, especially in attacking heresy. They have been called "the Pope's shock troops", and tricky (intricate and/or devious) arguments are sometimes described as "jesuitical". In medieval times, there were several crusader orders.

Other sites

See also: Churches in Ethiopia

_p085_Antiochia.jpg/440px-PARSONS(1808)_p085_Antiochia.jpg)

- Antioch 📍, today Antakya in Turkey, was a major center of early Christianity, and as of about 400 AD the third largest city in the Roman Empire.

- Antioch plus Tarsus 📍, Ephesus 📍 and Alexandria Troas 📍 (close to Geyikli-Dalyan) in Turkey, Athens 📍, Corinth 📍, Thessaloniki 📍 and Samothrace 📍 in Greece, Caesarea 📍 in Israel, were cities where St. Paul is supposed to have preached

- Seven Churches of Asia, Turkey, are seven major early Christian communities mentioned in the New Testament.

- İznik, Turkey 📍. As ancient Nicaea, the town was the site of the First and the Second Councils of Nicaea (or the First and the Seventh Ecumenical Councils), convened in 325 and 787 respectively, inside the former basilica of Hagia Sophia that still stands at the town square, converted into a mosque. The town is connected by the Tolerance Way, a hiking trail which commemorates the Roman emperor Galerius's (r. 305–311) Edict of Toleration ending the persecution of Christians, to İzmit (ancient Nicomedia), where the edict was published.

- Cappadocia, Turkey 📍. A refuge for the early Christians where they escaped persecution in numerous underground cities and colorful churches dug into the volcanic rocks of the area.

- Selçuk, Turkey. The House of the Virgin Mary over the hills outside the town is believed to be where Mary spent her last years. The stone building had long been venerated by the local Greek Orthodox, who visited the site annually on the Assumption (Aug 15). It is now a chapel that has been receiving a steady flow of Catholic pilgrims, including several popes, since it was reported in a series of visions of a bedridden Catholic nun from Germany in the 19th century.

- Wadi El Natrun, Egypt. Known in Christian literature by its ancient name, Scetis, this is an area of salt pans, salt marshes, and alkaline lakes below sea level and attracted ascetics such as the Desert Fathers, who practiced some of the earliest forms of Christian monasticism. While the area remains the main centre of Coptic monasticism, many hermits left the area after the Berber invasion of the early 5th century, with some eventually crossing the Mediterranean to found the earliest monasteries on Mount Athos.

- Mount Athos, Greece 📍. A peninsula with many Orthodox monasteries. For most of its history to this day, the area has been an autonomous monastic territory where women are not allowed at all, a .

- Patmos, Greece 📍. A small Greek island which the Roman Empire used as a place of exile for inconvenient people. An exile named John — who had been thrown out of Rome because his ranting sermons annoyed the authorities — wrote the Book of Revelation while living there, around 90 CE. Today it gets many pilgrims and parts of it are a . Most of the pilgrims, and the Monastery of Saint John, are Greek Orthodox.

- Taizé, France 📍. An ecumenical monastic order in Taizé near Mâcon, welcoming people seeking a retreat. A large community of visiting youth, families and people of all ages, in addition to the brothers and sisters.

- Aparecida, Brazil 📍. Home to the sanctuary of Brazil's patroness, the Holy Virgin Mary of Aparecida

- Several places in Germany are important in the history of Lutheranism: The Wartburg, near Eisenach, where Luther translated the bible into German (one of the first and most notable modern vernacular versions of the bible), Lutherstadt Wittenberg where the 95 Theses were written and where Luther began to preach against the Pope and other, smaller places, mostly in Thuringia.

- Longobards in Italy, Places of Power (568–774 A.D.), 7 religious buildings in Italy built during the Early Middle Ages, collectively a .

- Wooden tserkvas of the Carpathian region — 16 log churches in Poland and Ukraine, a .

- Walls of Jerusalem National Park. Has few historical aspects, but everything in the park is named after Bible references as the geological features of the park which resemble the walls of the city of Jerusalem very closely. Listed as a for its natural beauty. 2021-12-04

- Axum, Ethiopia — Home to the Church of Our Lady Mary in Zion (Tsion Maryam) complex, which is believed by Ethiopian Christians to house the original Ark of the Covenant that Moses built to house the stone tablets that the Ten Commandments were carved onto. The Ark itself is believed to be housed in the Chapel of the Tablet on the church premises, which is not open to the public; only the guardian monk may view the Ark according to Ethiopian tradition.

Talk

Churches tend to use the language of the country they are located in, though this is by no means true in all cases. There are many expatriate churches in many places using the language of a community's homeland, and in some churches another language is used for other reasons.

The Roman Catholic church used to employ the Latin language widely, although this has changed since the 1960s so that services are typically given in the language of the community. The Vatican is a place where Latin may still be observed in active use. Latin Masses are still offered in many other places around the world as well, and some people find the experience to be superior to a mass in the vernacular. The Roman Catholic church in the diaspora (in places outside the historical Catholic sphere) may also offer masses in the languages of Catholic migrants.

There is no unifying language among the Eastern Orthodox churches, though the Greek Orthodox Church, the head church of the Eastern Orthodox churches, uses Koine Greek as its main liturgical language. The Slavic-speaking Eastern Orthodox churches, such as the Russian, Bulgarian and Serbian Orthodox churches use Church Slavonic as their liturgical language, the exception being the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which switched from Church Slavonic to Ukrainian after being granted autocephaly in 2019. In Egypt, Coptic, a language descended from the ancient Egyptian language, is commonly used in the Coptic Orthodox Church within the Oriental Orthodox communion. Egyptian Christians have also attempted to revive the Coptic language as a spoken language outside religious uses with varying degrees of success.

The original languages of the Old Testament are the Jewish holy languages of Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic, while the original language of the New Testament was Koine Greek. Jesus is widely believed by historians to have been a native speaker of Aramaic. The earliest Christians, especially the educated among them, were usually fluent in Greek and the Septuagint, a Greek version of the Old Testament, was more commonly known among early Christians than the Hebrew Torah, which explains some readings of prophecies that make little sense with the Hebrew text in mind, like making a word that in Hebrew means "young woman" into the Greek word for "virgin" in a prophecy interpreted by most Christians to refer to the birth of the messiah. Aramaic continues to be used as the liturgical language in the Syriac churches.

Some theological disputes are better understood with the intricacies of languages like Ancient Greek or Latin in mind. For example, the phrase "not one iota less" is in part based on a debate whether God-father and Jesus were "homoousios" (of one nature) or "homoiousios" (of a similar nature). As can be seen by this when Greek proficiency in the West and Latin proficiency in the East declined, the churches naturally started drifting apart and ultimately split over disagreements that they may have been able to resolve had the language barrier not stood between them.

The most common English-language Bible is the King James Version that was translated from the original Greek and Hebrew by contemporaries of Shakespeare. However, many Evangelical megachurches use newer translations of the Bible that are written in modern vernacular to make their Bibles more accessible to youths, and many Lutheran churches in addition base the translation on the latest research.

Differences

Different Christian groups use different names for activities and events. For example, the word mass is commonly used in Catholicism, Anglicanism and some Protestant churches but practically never used in Evangelical or Orthodox churches, which use the term service and divine liturgy respectively instead. Also, while the term saint in Catholicism, Anglicanism and Orthodoxy refers to only a select group of individuals, in most Protestant churches the term saint refers to any born-again Christian. Also, Evangelical churches do not use the term saint in front of names, so when the Catholic church would say "Saint John" for the apostle, Evangelicals would just say "John".

See

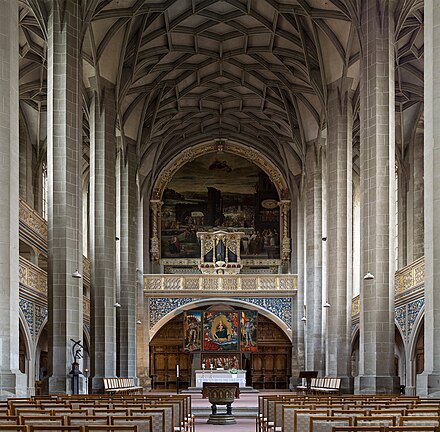

Churches

Many Christian houses of worship, particularly many Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican ones, are spectacular buildings. On their exteriors, many churches have stone carving, for example in their tympana and niches. In their interiors, many have priceless works of art, in the form of frescoes, framed paintings, sculptures, stained glass windows, mosaics, and woodworking. They may also have relics (the remains of body parts or objects associated with saints or other figures holy to Christians) that inspired the original construction of a cathedral, or famous icons of the Virgin Mary, which are primarily responsible for making the building a place of pilgrimage.

In addition, cathedrals and other large churches may have lovely bell towers or baptisteries with separate entrances that are well worth visiting, and particularly old churches may have a crypt that includes artifacts from previous houses of worship the current building was built on top of, and associated museums that house works of art formerly displayed in the church.

Protestant churches that are largely unadorned for doctrinal reasons can have a kind of serene, simple beauty all their own. In some old churches, what little was left from the Medieval – Roman Catholic – period has been restored.

In some places former mosques have been turned into churches (or vice versa) and more than one church has changed denomination due to the once common principle cuius regio eius religio (Latin that roughly translates as: Who owns the land decides the faith). This sometimes shows in architecture as well as adornments or the lack thereof.

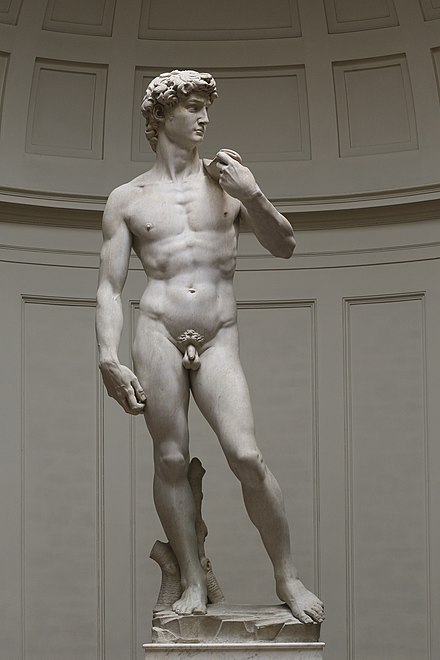

Christian art

Aside from the art you can see in churches, there is much sacred Christian art, especially framed paintings and sculptures, in art museums around the world, and there are also many beautifully decorated books of sacred Christian writing, including complete Bibles, separate Old and New Testaments, sets of Gospel readings for a year of masses, books of prayers with music notation for chanting or polyphonic singing (in which several different vocal lines intertwine in different ways) and books of devotional poetry.

Through the Middle Ages and up to the Renaissance, Christian art (including post-Biblical stories of saint and martyrs) was the highest genre in European art. At least up to the Thirty Years War, the Catholic Church was by far the most generous sponsor of artists.

One particularly notable style is that of the illuminated manuscript, in which a book is handwritten in calligraphy along with decorative and informative illustrations. Illuminated manuscripts are generally found in libraries — either public libraries, university libraries or indeed church libraries.

Do

Visiting a church

In many Christian churches, a man should remove his hat, and in some, a woman is expected to cover her head. Depending on the church and what is going on at the time, voices should be kept down, and mobile phones and similar devices should be set to silent.

In addition to their architectural, historic and cultural values, churches are places for:

- Personal meditation, contemplation and prayer between masses/services

- Worship services, which vary widely in style between different churches

- Confession of sins or/and counseling

- Religious education and spiritual direction

- Various sacraments, such as baptism, confirmation, weddings, and funerals

- Communal activities, such as shared meals or snacks

- Charitable giving and receiving

Many churches run concert series or other performances, some of which are world-famous. Some churches are known for having a great organist, chorus, or solo singers and instrumentalists. See Christian music below

Churches generally have pamphlets in plain sight of visitors, describing their spiritual mission, schedule of services, communal and charitable activities, what charitable and maintenance/restoration work needs contributions, who to contact to find out more information about all of the above, and often the history of the building and its artworks.

While most churches belong to a single congregation, which is responsible for all activities, some are shared, perhaps also with worldly authorities involved. In these cases information in one schedule or at one website may not be complete, but activities may be more varied.

The main services are usually held Sunday morning and on special occasions, but there may be morning or evening prayers and services of other kinds. If the church has services in more than one language, perhaps because of immigrant communities, some of these may be later in the day or at other times. There may also be Bible study, communal activities, concerts etc. Some of these activities may be in a community center instead of in the church.

If you are visiting the church to look at the architecture and art, it is better to choose a time when there is no service or other special activity. People may still sit meditating or praying, lighting a candle or otherwise use the church as church. Avoid disturbing them.

Some events may be more or less private even if doors are unlocked. If you want to attend a service – to worship or out of curiosity – going to one that is announced to the public should generally be safe. In touristic places there is sometimes an information desk where you could ask, otherwise you might find a church official with some spare time.