The Northern Lights or aurora borealis are a natural phenomenon that can paint the night sky with unearthly, surreal color. The Southern Lights or aurora australis also occur but are not as often observed.

To observers at far-northern latitudes, the Lights are a frequent occurrence, but many who live in more temperate climates have never seen them, even though they are occasionally seen as far south as 35 degrees North latitude. This article will help you improve your chances of seeing the Lights if you journey north.

The aurorae are caused by charged particles ejected from the sun. When these particles reach the earth, they collide with gas atoms and molecules in the earth's upper atmosphere, energising them and creating a spectacular multi-coloured light show. Charged particles are affected by magnetic fields, so the Lights occur mainly at far northern or southern latitudes near the Earth's magnetic poles.

The aurorae are caused by charged particles ejected from the sun. When these particles reach the earth, they collide with gas atoms and molecules in the earth's upper atmosphere, energising them and creating a spectacular multi-coloured light show. Charged particles are affected by magnetic fields, so the Lights occur mainly at far northern or southern latitudes near the Earth's magnetic poles.

The Lights look somewhat similar to a sunset in the sky at night, but appear occasionally in arcs or spirals usually following the earth's magnetic field. They fairly often look like moving curtains of light, high in the sky. They are most often light green in color but often have a hint of pink. Strong eruptions also have violet and white colors. Red northern lights are rare, but are sometimes observed.

The Lights are generally fairly dim, but sometimes bright enough that reading a newspaper on a moonless night is possible. Both brightness and how far from the poles they are visible vary according to three factors: time of year, an 11-year cycle in solar activity, and solar storms. These are discussed in more detail later.

Light pollution around cities can mask a dim aurora display. Therefore, areas at least 30 km from cities are preferred for viewing. The trick is to get far enough from cities for good viewing (generally easy, since most northern areas are not heavily populated) without taking undue risks in a climate that can easily kill you.

Understand

Contrary to intuition, seeing the Northern Lights isn't just a matter of heading north. The Lights occur mainly in a circular or elliptical band centered on the earth's North Magnetic Pole, which is not at the same location as the North Geographic Pole. The exact location of the North Magnetic Pole varies.

Until early in this century, the pole was moving slowly (about 10 km/year) north across Ellesmere Island in the nearly uninhabited far north of Canada. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the pole has been moving faster, for reasons geologists are not yet certain of. As of late 2019 it is out in the Arctic Ocean well north of Ellesmere, and moving toward Russia at about 55 km/year. Because of the movement, the advantages of being on the "right side" of the earth are becoming less pronounced, but there is still a slight North American bias in your chance of seeing the Lights.

Auroral displays aren't strongest at the pole; the band of greatest activity is offset from the Magnetic Pole by 20 degrees or so; the magnetic lines of force are curved and the curvature creates the offset. The Northern Lights oval, meaning the area with the highest probability of seeing the Lights, covers most of Alaska, northern parts of Canada, the southern half of Greenland, Iceland, northern Norway and the northernmost areas of Sweden and Finland, as well as the western half of the Russian north. There is a similar oval in the South; see the photo.

Regions such as the central and southern parts of the Nordic countries, southern Canada, the north-central United States and Scotland also frequently see Northern Lights, but not as often as directly under the Northern Lights oval. Svalbard sees Northern Lights less often than Northern Scandinavia, but is a place to observe the fainter Day Northern Lights visible during waking hours in its long polar night.

That said, the actual latitudes of the Lights vary considerably. In times of high solar activity (more on that later), the Lights may be seen in North America at latitudes as low as 35 degrees North, meaning that all but the southernmost parts of the United States may get a display. The offset of the Pole keeps solar storms from benefiting Europe quite as strongly, but most of the countries of northern Europe will get displays during periods of solar storms.

Planning

There is no guarantee of seeing the Northern Lights even if you are in the best areas at the best time, and there is some chance in others areas and seasons. However, a bit of planning will radically increase your chances. In short, pick somewhere on or very near the oval and go in winter.

Time of year

Darkness is required. Most Northern Lights locations are at high latitudes, in areas that get the "midnight sun"; there is no darkness from late April until mid-August, or even longer in far northern locations like Svalbard. Places within eight degrees of latitude south of the Arctic Circle, such as Yellowknife in Canada, experience "white nights", with only a few hours of twilight between dusk and dawn, at this time of year. In this period, no Northern Lights can be observed.

In the most intense Northern Lights areas, right on the oval, the lights are sometimes observed in any season but chances are best when it is dark after 6pm, from late September to late March.

On a yearly basis, the Lights are at their peak around the time of the equinoxes, in September and March. The reasons for this trend aren't fully known, but it's definitely real, not just an artifact of the weather or other viewing conditions. Also, if you are planning to do other activities during the day, this is a good time to visit because you can enjoy twelve hours of daylight and still have a good chance of seeing the aurora at night. Temperatures are also milder than in mid-winter.

Time of day

The time between 6PM and 1AM is the most intense period of the day. The highest probability within this timespan is between 10 and 11PM. However, this is a guideline, and during the Polar night aurorae can be observed as early as 4PM, and all through the night. The most intense displays last some 5–15 minutes each. In periods of strong activity, one can generally expect flares starting in the early evening, peaking around 10pm, and going on into the early morning hours.

Even with good clothing, few travellers can tolerate a long time outdoors in an arctic night and the nights generally get continuously colder from sunset until the morning sun starts to warm things up. Even if there are lights in the early evening, it may be best to set out at 9pm or so (sun time, check your timezone); this gives you a good chance of catching the peak display without being out too long or at the coldest times.

11-year cycle

In the longer term, auroral displays are correlated with an 11-year cycle in sunspot activity and other perturbations of the sun; the more restless the sun, the more aurorae. However, at the most favorable latitudes, the Lights are still likely to be seen even at solar minimum; it's mainly at lower latitudes that they get scarce during the inactive times. The last maximum in solar activity was in late 2013.

Solar storms

In addition to these more or less regular variations in frequency of the aurora, there are also less predictable, erratic displays resulting from solar storms. Some of these, particularly near solar-activity maximum, can lead to visible Northern Lights remarkably far south, if you're in an area with clear, transparent night skies. The largest recorded solar storm took place in 1859; the Lights were bright enough to read a newspaper in Boston (42°N) and visible as far south as Mexico.

The Alerts section below will help you stay on top of solar activity and prepare for some viewing when a solar storm does occur.

Clear skies

Last but not least, don't forget the weather forecast — aurora occur very high up in the atmosphere, and if there are clouds in the way you will not see anything. In Northern Scandinavia, the weather is notably better towards the end of the Northern Lights season (February-March), than in the beginning. The weather is probably the most important success factor in the areas under the Northern Lights oval, where there are visible Northern Lights on up to 80% of all clear nights.

Prepare

Alerts

If you have the luxury of being able to travel into aurora-viewing territory on short notice, you can improve your chances of seeing something by being aware of "space weather," the things going on beyond the earth's atmosphere as a result of solar activity.

A good site for space weather information is operated by the (US) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Measurements aboard the NOAA Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite are used for plotting maps of current extent and position of the auroral oval around both poles. Another useful tool is NOAA's test version of their OVATION Model (dead link: January 2023). It predicts intensity and geographical location of the auroral oval based on current solar wind conditions and interplanetary magnetic field virtually in real time. The maps also show the observation limits of current aurorae. The commercial site Space Weather presents much of the same information in digested, more accessible form.

A good site for space weather information is operated by the (US) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Measurements aboard the NOAA Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite are used for plotting maps of current extent and position of the auroral oval around both poles. Another useful tool is NOAA's test version of their OVATION Model (dead link: January 2023). It predicts intensity and geographical location of the auroral oval based on current solar wind conditions and interplanetary magnetic field virtually in real time. The maps also show the observation limits of current aurorae. The commercial site Space Weather presents much of the same information in digested, more accessible form.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks maintains an Aurora Alert website. For Finland, the Finnish Meteorological Institute has an activity forecast and current data about magnetic activity. The Icelandic MET office provides a lights forecast for Iceland including cloud cover prediction.

Activity is mainly predicted from the readings taken by the NASA Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) and Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellites, which give a one-hour warning. Solar wind activity is characterized by three principal figures: the north-south component of the magnetic field (Bz), speed and density. When Bz is negative (southward), solar wind particles are best able to enter the atmosphere and give rise to aurorae. At high velocities, auroral activity may occur despite a moderately negative Bz. In geomagnetic storms, Bz fluctuates rapidly. Overall geomagnetic activity is characterized by the planetary K-index (Kp), for which predictions are issued. A Kp of 5 or higher occurs in storms and generally makes auroral viewing possible well South of the oval in the northern parts of Europe and the continental U.S.

Longer-term estimates can be made by observation of the Sun for bursts. However, the physical models are poorly developed, partly because only two satellites, ACE and DSCOVR, observe the solar wind before it hits the Earth, and the predictions are rather unreliable. The approximate day can be predicted, but whether the burst hits the Earth face-on and exactly when and at what force remains unknown. "Nowcasting" on the ground is done by measuring magnetic field fluctuations, and there are webcams pointed at the sky for directly seeing the aurorae. The NASA Polar and Environmental Satellites (POES) directly measure the extent of the auroral oval, but the satellites pass the pole about 14 times a day and thus the picture can be couple of hours old.

If a major solar storm develops that is forecast to have a good chance of producing Northern (and Southern) Lights, your time to respond will be measured in hours to a few days, rather than either minutes or weeks. The particles that create the aurora move much more slowly than light, so a storm can be observed well before the particles it produces reach Earth, but the time difference is not enormous. The forecasts will usually include some indication of how far from the magnetic poles the activity is expected to extend. For purposes of travel planning, it's a good idea to plan conservatively and go to a locale somewhat closer to the pole than the predicted maximum extent of the aurora; things don't always work out as forecast, and the Lights may be relatively weak and/or confined to the northern horizon if you're at the southern edge of the activity, either limitation possibly creating difficulties for you in viewing owing to light pollution.

Clothing

Because aurorae are usually visible at night in the colder months of the year, the observers tend to spend long hours in cold darkness. It is essential to dress adequately to minimize the unpleasant side of the auroral experience, and almost impossible to dress too warmly.

Because aurorae are usually visible at night in the colder months of the year, the observers tend to spend long hours in cold darkness. It is essential to dress adequately to minimize the unpleasant side of the auroral experience, and almost impossible to dress too warmly.

In any area that gets severe winters, winter clothing will be widely available, but specialist shops catering to skiers, mountaineers or wilderness backpackers generally offer the best choice. Further south, these specialists may be the only places with winter equipment.

In remote northern locations where food, fuel and equipment have to be shipped in, prices on more-or-less everything can be very high. Major northern cities tend to have better prices than more isolated areas, but still higher than in areas further south. Most travellers should buy much of their equipment before setting out; this gives more time for shopping, saves money, and avoids arriving in summer clothing when it is seriously cold outside.

Some travellers should plan an extra stop for shopping; for example, going from Miami (where good winter gear is likely to be hard to find) to view the Lights in Churchill (where it is likely to be expensive and selection limited), one might stop in Chicago, Toronto or Winnipeg to outfit oneself.

For specific information on winter clothing, see Cold weather. Remember that you will have to use your fingers, so a combination of gloves and mittens can be useful.

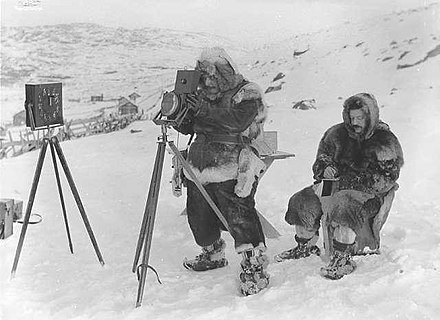

Photography

Taking good pictures of the Northern Lights is very difficult, since they're fast-moving, often faint and against a pitch-dark background, all of which befuddles consumer point-and-shoot cameras. Almost any interchangeable lens camera can handle the job, given the right lens, but the typical "kit lens" sold with them will almost certainly not be fast enough and may not be wide enough either. Lens focal lengths

In discussing focal length, we assume a 35mm film camera or "full frame" digital camera. For other types of camera, the actual numbers are different but the "35mm equivalent" is often quoted.

Long exposures are often required to capture faint lights. Here's what you need for a sporting chance:

- A camera that supports manual exposure (5 to 40 seconds)

- A fast lens (aperture f/2.8 or better). Typically, a wide-angle lens is used to get a large area of sky.

- Fast film (800 ASA or better), or equivalent ISO setting on a digital camera

- A tripod to hold the long exposure

- Cable release or self-timer to trigger shots without stirring the camera

Even better, for some cameras a remote control is available. Some cameras can use a wireless smartphone connection as remote control, but few smartphones are made for the conditions.

- Manual focus. It is not recommended to just focus your lens to infinity, instead it is best done by aiming at the Moon or a bright star (ideally in the live-view mode and using the maximum zoom).

- Multiple spare batteries and memory cards: only having them will ensure they won't be needed. Keep the spares warm.

- What you don't need is the lens filter: it can cause interference, so better take it off your lens.

With a digital camera shooting in RAW format (or at least JPG + RAW) is a good idea: if something goes wrong in the field, there is more space for corrections in post-processing that way.

With a digital camera shooting in RAW format (or at least JPG + RAW) is a good idea: if something goes wrong in the field, there is more space for corrections in post-processing that way.

Avoid breathing on the lens, the viewer or the display to prevent frosting them up. A light source such as a flashlight or headlamp can be useful when setting up the camera and tripod, and a smartphone is handy for alerts and forecasts. However, you need to get your eyes adjusted to darkness, so it is a good idea to limit use of these and set both phone and camera LCD displays to minimum brightness.

The ideal location has no light pollution, offers some shelter against wind, and is easily accessible. On a cold arctic night, you definitely want to avoid lugging camera and tripod a long distance or standing around in windy conditions waiting for the right shot. Moreover, wind tends to shake the camera, which is a problem in long exposures. A bigger, sturdier tripod helps with that, but is even worse to lug around. If possible, do some scouting by day so you can go straight to a good location at night. It is not always possible to find a great location, but even a reasonable one can give better photos with less discomfort.

Also, try to get something interesting in the foreground; the Norwegian photo below is a fine example. A shot of just the sky and some snow can be a bit boring even if the Lights are good.

Either a zoom (variable focal length) or a prime (single focal length) lens can be used; each type has advantages. Zoom lenses are more flexible; you can adjust quickly for different sizes of light display. Primes are generally significantly faster than zooms, lighter and more compact; in many cases they also give a sharper picture than a zoom lens set to the same focal length.

Wide-angle lenses are the commonest choice for photographing the lights. They give some distortion, even producing "fish-eye" images in extreme cases. The photo to the right was taken with a 16mm lens; the horizon appears curved and the trees in the foreground appear slightly off vertical, but some viewers would not notice this distortion and few would find it bothersome. The Scandinavian photo above used an even wider lens and has more distortion. A slightly longer lens, perhaps 24mm, would reduce the distortion but cover less of the sky. This is where zoom lenses have a significant advantage over primes; with, say, a 16–35mm zoom you can adjust each shot to get the best trade-off between distortion and coverage. In other conditions, you might carry several primes and adjust by swapping lenses, but this is remarkably inconvenient in the field in an arctic night.

A faster lens or a high-ISO camera setting can reduce exposure time, which is good. The photo to the right used an F2.8 lens and 25-second exposure. With F4, it would need 50 seconds, at or perhaps beyond the upper limit for practical shooting. An F1.4 lens would cut the time to around six seconds. This is quite likely to give a sharper photo because the lights move less during exposure, and it allows a bit more control over the shot; if you hit the shutter release when the sky looks particularly interesting, it is more likely to stay that way for a few seconds than over a longer time. This is where prime lenses have an advantage; they are often quite a bit faster than zooms.

Combine a fast lens with a camera that allows high ISO settings and you might get exposure time down under a second, but it is not certain that this would give a better photo. High ISO settings give more noise in the image and you might lose more from that than you gain from the shorter time.

Fast wide lenses are expensive. Checking full-frame Canon lenses on an American vendor's site mid-2013, the cheapest lenses that might be suitable for shooting the Lights are a 40mm F2.8 at about $150 or 35/2.0 near $300; those are not wide enough to be ideal, but they would be usable and anything better is more expensive. More typical choices — for someone with a nice lens collection in hand or a good budget for building one — would be 20 or 24mm F2.8, 28/1.8, or the 17–40 F4 zoom, in the $450 to $750 price range. The ideal choice might be either a 24/1.4 prime or 16–35 F2.8 zoom, but these are high-end products mainly for professional photographers; either is around $1500. An ultra-wide 14mm F2.8 is a very good choice, and while those with auto-focus cost over $2000, some manual focus versions are available for a significantly lower price. Other brands have a different set of products and prices, but the overall pattern is similar. Companies other than the camera manufacturers also offer lenses, but again the pattern is similar.

See travel photography for more general discussion.

Locations

Northern Lights usually form about 100 km (60 miles) above the surface of the earth. In principle, all areas under the Northern Lights oval are good observation points. However, most of these areas are remote and inaccessible, and suffer harsh climatic conditions.

Northern Lights usually form about 100 km (60 miles) above the surface of the earth. In principle, all areas under the Northern Lights oval are good observation points. However, most of these areas are remote and inaccessible, and suffer harsh climatic conditions.

When selecting an observation site:

- If using a car, stay close to it. A typical car heater cannot actually keep a large metal vehicle warm when it is well below zero outside, but it is better than nothing and a car does provide shelter against wind. In really cold weather, leave the engine running even when you are away from the car, since the engine may have trouble starting again.

- Try finding accommodation in an area known to be good for viewing the Northern Lights. This may include a cottage, wilderness hut, a heated tent or similar shelter. This avoids long drives late at night to get to and from the viewing area.

- Avoid locations with light pollution; try to get away from populated areas. If this is not possible, try to have at least the northern view free of light pollution.

- Avoid steep hillsides or other major obstacles to the north.

Consider bringing a tent or just a portable windbreak to provide some shelter from wind. Also vacuum flasks for hot beverages.

Viewing or photographing the Lights is an activity where hiring a local guide or paying for a tour is often worthwhile. A guide's local knowledge can help in several areas: coping with the weather, finding good sites, choosing good routes, and avoiding close encounters with dangerous wildlife such as polar bears or musk oxen. Also, a guide or tour company will have vehicles and other equipment suitable for the conditions. In remote areas it may not be possible to rent a vehicle or bring your own and, even if it is possible, it is not advisable unless both vehicle and driver are well prepared for winter driving. Some tours offer unusual transport options such as snowmobiles or sleds pulled by dogs, reindeer or horses; few tourists could safely drive those, and no owner of valuable animals is likely to allow a visitor to handle them unsupervised.

Various locations provide some kind of infrastructure, like tours, observation points etc. Here are lists of some major ones, in approximately west-to-east order:

North America

See also: Winter in North America

.jpg/440px-Flickr_-_DVIDSHUB_-_Alaska_Aurora_Borealis_(Image_1_of_2).jpg)

- Fairbanks, Alaska: famous for aurora viewing, with many tours and sites that cater to aurora watchers.

- Yellowknife, in Canada's Northwest Territories, also with many tours

- Churchill, on Hudson's Bay in Manitoba, is right smack dab in the center of the auroral belt, and offers the opportunity to see (lots of) polar bears on the same trip.

- Isle Royale National Park, Upper Michigan, is a leave-no-trace park with no tours and few facilities, only the possibility for visitors to see the lights themselves in a place with no light pollution.

North Atlantic islands

- Kangerlussuaq, Greenland: very high chance of seeing the Lights from November to March. If husky and snowmobile rides are desired, mid-late winter is recommended.

- Mývatn, Iceland: offers the unique experience of observing aurorae while soaking in a natural geothermal bath. The capital, Reykjavik, serves as a base for many tours.

- Berneray, Outer Hebrides: this remote Scottish island offers suitable conditions for northern lights observation due to low light pollution.

Europe

See also: Winter in the Nordic countries

- Abisko, Northern Sweden. A popular place where the northern lights can be watched from the Aurora Sky Station at the top of the mountain Nuolja.

- Tromsø, Northern Norway, is an easily accessible location with mild weather and numerous excursions. However the coastal location makes it susceptible to overcast conditions. Nearby Skibotn enjoys a dryer climate (very dry for Norway); this makes for better viewing opportunities. Another nearby location is Senja island.

- Alta, also in Norway but further to the north-east and known for prehistoric rock carvings, is marketed also as a place to watch northern lights.

- Jukkasjärvi, Northern Sweden, is the site of the original Ice Hotel, with excellent viewing infrastructure.

- Kilpisjärvi, Inari and Utsjoki in Finnish Lapland all have quite dry weather and little light pollution. The ski resorts Saariselkä in Inari and Levi in Kittilä have accommodation in glass igloos specially designed for enjoying the northern lights.

- The Kola Peninsula of Murmansk Oblast is Russia's most popular viewing spot.

The likelihood of seeing aurorae rapidly decreases when going south. In Helsinki, aurorae occur about once a month, and are usually masked by light pollution or clouds. Aurorae seen further outside of the auroral belts may also be much less vivid, with fewer colours.

Cruise ships

A luxurious way to see the lights is to take a cruise ship along the coast of Norway or Alaska, or toward Antarctica for the Southern Lights, in the appropriate season. Cruises tend to be expensive, but the costs may be quite reasonable compared to flying to a good site on land and paying for accommodation and tours there. Viewing the Lights by just strolling on deck after dinner is much more convenient than being driven somewhere to stand in the snow, and the chance of encounters with dangerous wildlife is lower.

There may be problems with this; not all cruise lines run in winter and it is extremely difficult to get good photos from a moving ship when the subject requires long exposures, as the lights generally do. If the cruise is not specially for aurora viewing, chances are that light pollution from the ship itself is an issue.

In flight

Many travelers in the northern latitudes find themselves treated to an aerial view of the lights. It's probably not realistic to plan to see them while on a plane, but if you find yourself taking frequent flights in upper latitudes, consider opting for a window seat on the northern side of the plane. If the show is good enough, the captain will usually make an announcement.

If you thought cruises on the seas were expensive, you probably won't be interested in heading up into space, but orbital flight at around $35 million/person is a pretty surefire way to see the lights, both Northern and Southern, with zero light interference, and quite a grand view!

The Southern Lights

Aurorae happen in an oval about the South Magnetic Pole just as they do about the North one, and the South Magnetic Pole is similarly offset from the geographic South Pole. Would-be observers of the Southern Lights or Aurora Australis benefit from the happy accident that the offset of the South Magnetic Pole is generally in the direction of Australia, although the Pole itself is still in Antarctica like the geographic one. The southern parts of Australia and New Zealand get more than their share of Lights relative to their latitude.

Aurorae happen in an oval about the South Magnetic Pole just as they do about the North one, and the South Magnetic Pole is similarly offset from the geographic South Pole. Would-be observers of the Southern Lights or Aurora Australis benefit from the happy accident that the offset of the South Magnetic Pole is generally in the direction of Australia, although the Pole itself is still in Antarctica like the geographic one. The southern parts of Australia and New Zealand get more than their share of Lights relative to their latitude.

In particular, Tasmania and the South Island of New Zealand are places where the Lights can be observed several times a year. If conditions are right, Hobart and Invercargill offer the best chance in places that are quickly accessible from within Australia and New Zealand. Although Christchurch has a geographic latitude south of Hobart, its "geomagnetic latitude" is further north, and aurora there are no more likely than southern Victoria. Check the space weather while you are travelling.

All these locations are still outside the auroral belt itself, so the odds of catching the lights during your trip there are not good. Because of the skew towards the Eastern Hemisphere, it is not reasonable to expect any viewing from Patagonia, and it's not that likely you'll see them even from the Antarctic Peninsula. The best place to view them would be Antarctica's Ross Sea via Macquarie Island (Australia) or the New Zealand Subantarctic Islands. The best viewing would be from the boat itself. The closest island to the auroral belt that has a good range of tourist accommodation is Stewart Island.

There is day trip flight from Sydney to see the Southern Lights (A$1,295+).

All of the considerations about maximizing your chances of seeing the Northern Lights apply equally to seeing the Southern Lights, except that the Southern Hemisphere seasons should be taken into account in regards to maximizing the hours of darkness.

See also

- Astronomy

- Midnight sun — at latitudes where there's dark all day in the winter and people travel to see the Northern Lights, there's usually light all night in the summer.