Wilderness backpacking

Wilderness backpacking

Wilderness backpacking is a form of self-reliant travel that affords opportunities to see sights available no other way.

Understand

Carrying everything you'll need to get along for several days in the wilderness isn't everyone's idea of a "vacation", but if you don't mind including some physical effort and additional inconvenience in your travel time, it's an ideal way to truly "get away from it all", and hopefully see some truly majestic scenery.

Carrying everything you'll need to get along for several days in the wilderness isn't everyone's idea of a "vacation", but if you don't mind including some physical effort and additional inconvenience in your travel time, it's an ideal way to truly "get away from it all", and hopefully see some truly majestic scenery.

Landscape

Before taking off on a backpacking trip, assess what kind of territory you'll be traveling through. Distances on a map never look that hard to cover, but once you find yourself staring up at a 400-foot ridge standing between you and tonight's camp, it's a different story. Topographic maps will give you a better idea of what you're getting yourself into, as well as being essential for navigation if you're going off-trail. Unless you have an uncanny sense of direction, you'll probably need a compass, or at least know how to discern north from the time. GPS can be nifty, but many feel it takes the adventure out of hiking, and it may not always work as well as the sales pitch suggests.

Climate

Find out what kind of weather you can expect at the time of year you're planning to go. When's the rainy season? What's the temperature range? Keep in mind that going up in altitude is like going up in latitude. Daytime temperatures may be pleasant, but how cold does it get at night?

Culture

Even when wilderness backpacking, you will meet local people: those in the village where you do the final preparations, people living in the wilderness (there are few truly uninhabited places on earth), park guards and other authorities. While preparing, get some feeling for what the wilderness means or has meant for people living there or nearby. You should also do the normal checks on diseases, transport in and out, obstacles to access, local customs you should be aware about etcetera.

Fees and permits

Check with the local authorities if you'll be using a state/provincial/national park to see what fees there are for use of the park, and for the trails and campsites, if any. In some parts of the world, right to access may give you permission to hike on privately-owned undeveloped land, but elsewhere – especially the United States – be sure to get permission (unless you want to risk prosecution – or gunshot – for trespassing).

Prepare

It is very important to be well prepared for your wilderness travels and hikes. You should pack the correct clothes, sleeping gear, food and drinks, safety equipment and first aid kit in case something happens in the wild. Do all you can to avoid going "freestyle" and heading into the wild without letting others know your plans, your destination, your expected return time, and a "hot" deadline at which your absence should be considered an emergency by a trusted friend. If parking at a trailhead, you can also place a folded note above the car's sun visor indicating your identity and expected return day & time. To avoid trouble if you should lose the car key during the hike, you can hide a spare key nearby just in case.

Physical fitness is decisive for a good experience. If you are not used to physical exercise, you should begin at least a few weeks before the trip. Avoid high-risk exercise which might inflict injuries, though.

You also need to be mentally prepared for wilderness travels. You are going to be challenged physically and mentally and if you aren't prepared for the rigors along the way, you may give up.

Check the local declination and know how to compensate. You will probably carry a magnetic compass, and if it shows 15° wrong without your knowing, you will easily get lost.

Get around

In most countries "get around" means "walk", though some long-distance wilderness expedition could be undertaken by cross country skiing, canoeing or horse riding.

In any case, footwear is one of the most important aspects of backpacking. Traditional hiking boots could kill a small animal just by being dropped on them (empty) from a few feet up, but modern boots can be much lighter, reducing the drag on every step you take. You don't necessarily need to spend hundreds of dollars on state of the art boots, but odds are that your favorite athletic shoes or street shoes will leave you very uncomfortable and hold up just as poorly. Stiff soles and plenty of ankle support are a good idea if you're going over any rocks. Some prefer light footwear that give more control, but this requires good ankles and good balance, and can be risky even then if tired. Don't rely on your abilities without sufficient experience.

Buying a new pair of boots just before your trip is a very bad idea. Break the boots in, first with short walks, then longer ones. Wear them around for a week, and you'll know where they rub, if you want to put soft insoles in them, etc. They should conform to the shape of your foot, so by the time you're ready to hike, your boots are too. The break-in period also helps your feet get used to the boots, building up thin callouses in the spots where they rub a little.

Like with sturdiness, there are two strategies for wetness: either have water resistant footwear – that will get moist by sweat even if claimed to be breathable, and at some point might get drenched by a badly timed misstep – or footwear that can be dried overnight (just keep walking to keep your feet warm, and have adequate socks).

In winter your footwear is even more critical. Your boots need to be warm enough, and any wet footwear – be it by wet snow, a creek hidden under snow or just sweat – can cause hypothermia and frostbite in cold temperatures, and will at least be very uncomfortable. If skiing, your choice of footwear is limited to what fits your bindings. Greasing is the traditional way to make boots water resistant, and wool stays warm even when quite moist. If your boots get drenched, get rid of most of the water, put on dry warm socks and a plastic bag, and then the boots (you have suitable plastic bags, don't you?). Leather boots should be dried at moderate temperature, don't put them close to a fire. If you have a warm shelter, try to get rid of as much snow as possible before it melts on the boots.

You may want to look into socks that are specifically for hiking. These socks will be of a sturdier fabric that will provide more resistance to the wear and tear you're putting them through. Poor quality socks can result in toes rubbing against the inside of the shoes, or that your socks creep down towards your toes.

If the terrain is especially challenging, or if your knees aren't what they used to be, you might benefit from using a hiking stick or a pair of trekking poles (like cross-country ski poles, but without the baskets – and the skis). They aren't just for the feeble; they can improve your balance and increase your pace by adding some power from your arms to your propulsion. A hiking stick is also often needed when fording. A sturdy chest-high branch (not pulled from a standing tree) will do, or you can buy a telescoping staff or set of poles. Some of them can double as a camera monopod. And while this usage isn't recommended, you'd probably rather face an angry cougar with a pole in your hand than without one.

Wear

The type and quantity of clothing to wear depends heavily on the location and season. The key strategy in all but the hottest climates is to layer your clothing. If the temperature is going to vary between night and day (and it probably will, even – especially – in hot deserts), carrying a set of clothing for the warm times and another set for the cool times will take up extra space and add extra weight. Instead bring clothes cool enough for daytime hiking, and bring extra layers to put on over them when it cools off after dark. "Convertible" slacks are handy in warmer weather, allowing you to zip off the legs and turn them into shorts when the day gets warm, or back into long pants for wading through prickly plants.

Packing at least one complete change of clothes ensures that if any item you're wearing gets soaked (by rain, a misstep crossing a stream, sweat, whatever) you'll have another to wear instead. This is especially important for socks, which are both the most likely item of clothing to get wet and the most important to keep dry. Spare boots aren't practical, but a pair of cheap flip-flops or loose-fitting light-weight shoes will give your feet a chance to breathe when you're not on the trail, and give you something to wear after you accidentally dunk your foot in a pond while collecting water. This strategy also works for some other heavy items of clothing. You may not need a complete change for everyone in the company, coordinate items important enough but unlikely to need a change.

Although cotton is normally comfy, park rangers call it "death cloth". It soaks up water many times its weight and hence its drying time is very slow, making it a less-than-ideal choice for undershirts and underwear you'll be wearing next to your sweaty skin; synthetic fabrics such as capilene will "wick" moisture away from your skin, and can better keep you both cool and dry. Many discount stores will also sell suitable shirts in their sports department if you don't want to drop the money on the specialty brands. Cotton also doesn't keep you warm when it gets wet; wool is a better material for your socks and outerwear. Cotton t-shirts as a middle layer or for sleeping in are fine.

If you're expecting rain, your best solution will naturally be waterproof overcoat, boots and trousers or gaiters. However, you can often cope with rain even if you don't have those. You should dress in 2–3 layers (even more if it's really cold) which would prevent most of the rain from getting in. Since it's likely that some water will penetrate through the outer layers, you should take them off (despite the cold) whenever there's a break in the rain or if you find good cover, to allow the water to dissipate from the inner layers. On these occasions it's best to also hang the outer layers to dry; if you're on the walk, spread them across the back of your backpack. Also, if you don't have waterproof shoes and trousers, you may find it best to wear three-quarter pants that don't get all the way to your ankles. If the pants are too long, they'd get soaked with water and mud that will hinder your walk and will even wet your socks inside your shoes. Additionally, you should take advantage of every opportunity to dry your cloths, such as at campfires. Just be careful not to put your shoes too close to any source of heat, as rubber melts at surprisingly low temperatures, even if it doesn't seem to be all that close to the fire, and leather likewise doesn't like high temperatures.

Do with this information what you wish: Humans in many cultures across countless centuries have lived without freshly laundered underwear every morning. Also, keep in mind that the kind of underwear you normally wear may not be ideal for backpacking; women will probably prefer a "sport" bra that provides more support and no hooks in the back, and men may find that briefs provide less opportunity for skin-to-skin chafing and bunched up fabric than boxers.

Carry

There are two basic kinds of backpacks used in wilderness travel: internal frame and external frame.

The external frame is the more traditional variety, consisting of a metal frame that's strapped to your hips and shoulders, and which your sleeping bag, tent, and the fabric pack itself are strapped to. They're better for keeping your gear organized and accessible, and a bit cooler to wear, because they leave small gaps for air to move between you and the pack. They're the best option for the heaviest loads.

Internal frame packs have become very popular in the last couple decades. They use a more flexible frame built into the fabric of the pack itself, which allows you to carry the weight closer to your body, improving your balance. One trade-off is the lack of back ventilation, another that fastening any additional load (such as packing of your fellow who hurt his leg) comfortably is nearly impossible.

With either kind of pack, be sure to adjust the straps to put as much weight as possible on your hips, rather than your shoulders. The shoulder straps should mostly be keeping the pack from falling backward, not actually supporting its weight. This will save lots of wear and tear on your back and shoulders, making for a much less painful trip.

Some people prefer to bring along at least one of anything they might need, and others opt to travel more lightly, giving up convenience and comfort for mobility. But if your pack weighs more than a quarter of your body weight, it is probably too heavy.

Often you will have to climb up a mountain to see a glacier or a lake, just to return later—in that case consider leaving your (heavy) luggage and enjoy the trail without the burden. Depending on where you are you might either want to hide your luggage where it cannot be found by thieves or in a place where it is easily seen, preferably by a landmark on the trail, so that you cannot miss it. Finding the exact same place again is sometimes surprisingly difficult. Having GPS does help, if you save the coordinates and the device works as it should.

Eat

See also: Outdoor cooking

You'll want "light" meals, not in the sense of fat or calorie content, but in terms of how much the food weighs in your pack. In fact, you may want to lay off a lot of your "healthy diet" habits for the duration of your trip, because you'll want those extra calories, and fats are a good compact source of all-day energy. Wilderness camping is the very kind of lifestyle that led homo sapiens to develop a fondness for that kind of food. Depending on the length of your trip, food could make up a substantial fraction of your pack weight (figure at least a pound or half a kilogram per day). Since water makes up a large percentage of the weight of most foods we eat, and presumably can be found along the way, the obvious solution is to pack foods you can "just add water" to.

- Breakfast – Oatmeal is a good option: inexpensive, lightweight to carry, and easy to prepare. Measure portions ahead of time into zip-lock bags for convenience. Add a spoonful or two of brown sugar to make it more tasty. Berries found on the trail or brought as dried (possibly as a commercial powder) add even more taste. Peanut butter can likewise be bought as a lightweight powder.

- Lunch – You might welcome lunch as an excuse to stop to eat during the day, but preparing food on the trail can be a nuisance, so on-the-go foods like trail mix, granola or energy bars, or peanut butter are handy. For short trips, or for the first day or two of longer trips, you can bring semi-perishable foods such as fresh fruit or bagels. If you want a warm meal, you can heat water in the morning, carry it in a thermos bottle and add it to the dried components at lunch.

- Dinner – To restore your energy at the end of the day, freeze-dried foods are your most practical option. All sorts of pre-prepared dishes are available, mostly combinations of noodles, rice, chunks of veggies and meat, and sauce. Many can be prepared in the packaging they come in, making clean-up easier: just add boiling water, mix, and wait a few minutes. Especially with the sauce of hunger added, they can be quite tasty.

Consider bringing a camping stove. It's not as folksy as preparing food on a campfire, but it's more considerate of the environment, safer and more efficient. For most hikes a gas-powered camp stove is a good choice, but on long hikes, where one gas canister would not suffice, "multifuel" stoves may be more weight efficient, and finding fuel near your destination may be easier. There are also stoves using e.g. ethanol. See outdoor cooking for some more things to take into account.

Usually you don't want to scavenge firewood from the wilderness you're there to admire, but in a forested backcountry area that is not heavily visited, there is plenty of wood, and you may satisfy your needs without significantly affecting the environment. If it is allowed to make backcountry fires in your area, this may be an option. Try to limit the wood you gather to small branches taken from the ground, not anything broken from trees (living or dead) – and keep your fire small. You will want to be able to make a fire in emergencies, so research what tinder and firewood is available locally, and pack some tinder.

Some campsites have fire pits or grills available for cooking. If you use these, make sure your taking firewood won't degrade the experience for others; small branches taken from the ground is usually the best option. If you cannot find enough of these, or you wouldn't leave enough for those coming after you, don't make that fire. Some sites may even provide firewood, ready-made or for you to chop, or some ready-made to be replaced by that chopped by you.

A lot of food can be eaten without cooking also (like oatmeal and freezedrieds), if need be, or to minimise the need for firewood and carried fuel.

Keep pots and pans to a minimum, both for weight and clean-up reasons. If camping with someone you're in the habit of kissing, sharing a pot of food instead of dishing it out onto plates isn't a hygiene issue (but may become a relationship issue if you don't share equitably). In fact, if you mix and eat your freeze-dried meals in the packages they came in, and your oatmeal in the baggies you packed it in, you can get away with just a single pan for heating water, which won't even have to be washed. Stick to stewy and spoon-able food, and you may not even need to bring a fork or dinner knife.

By all means, reduce the risk of starting a wildfire.

Drink

Boiling Water?

If you are boiling water to kill bacteria and viruses, water should be brought to a rolling boil for 1 minute. At altitudes greater than 6,562 feet (greater than 2000 meters), you should boil water for 3 minutes. Instead of boiling water in the morning before heading out on your hike, consider boiling water at night over a camp fire or camp stove right before bed. Storage of hot water in drinking bottles can give a head start in heating up a cold sleeping bag and will be refreshingly cold for drinking the next morning.

Be prepared to drink more fluids than you're used to.

You might be able to take all the water you'll need for short trips of a couple days, but not for anything longer. Some areas will have clean water available on the hiking trail. In more remote areas, you'll have to collect water from lakes and streams. Check with the local authorities to find out which water supplies they recommend, and what precautions to use with them. Depending on which micro-organisms are common in the area's water supply, they may recommend using water purification tablets (usually iodine-based), micropore water filters (various brands are available), or boiling the water for several minutes. If boiling, remember that at higher elevations, water boils at less than 100°C, so you will need to boil longer. Filtration or purification tablets are less hassle for water you'll want cool enough for refreshing drinks as you hike. Filtered water tastes best. Purification tablets impart a taste and should only be used for a few weeks at a time, due to their iodine content.

Sweat depletes your body of sodium as well as water. This is especially true in the hotter climates and the sodium loss can be just as serious as dehydration, but cannot be as easily noticed (some symptoms are having a loss of appetite and headaches). Drinking water does not restore sodium into your system; in fact it lowers sodium levels in your blood even further. In some countries, sports drinks with dissolved salts including sodium (on the label, dissolved salts are called electrolytes) are available. Powdered sports drink mix is a convenient option. Another way to replenish your body's sodium level is to have a soup that is a little bit saltier than you are used to at the end of each day.

Sleep

Lightweight synthetic insulating materials have been developed for sleeping bags in the last few decades, but old-fashioned down remains a good option. Down still offers the most warmth for the least weight and it packs up more tightly than synthetic fill. However it loses its warmth-keeping ability when it gets wet and takes longer to dry (modern down products are water resistant to some degree). Down-filled bags last longer but are also more expensive. Mummy-style bags will keep you warmer than rectangular ones (less space for your body to heat up) and take up less room in a tent, but don't plan on moving around much if your sleep in one.

Sleeping bags are typically rated for the coldest temperature in which they'll keep you warm enough. If there are separate extreme and comfort ratings, the former is a guess about what an adult healthy man would survive, not necessarily unharmed. There are standards for these ratings, but the scale itself is something of a guess, since they don't know what your metabolism is like, how sensitive to cold you are, or for that matter what you'll be wearing to sleep in. Select your bag based on the coldest temperature you can anticipate experiencing (remember that night temperatures are what count). If you can see yourself ever hiking in high altitudes, in high latitudes, or in spring or autumn, get a 3-season bag with a lower temperature rating than those for summer. And if there's ever a chance you'll see snow when you camp, get something in the 0°F (−20°C) range for "extreme". Additionally inserting a simple liner – made of a single layer of silk (preferable) or other lightweight fabric – can really raise the temperature in your sleeping bag. Two lesser sleeping bags one inside the other (only one used in warm nights), is a heavier budget option, but those aren't rated, so try them out before trusting them.

The fluff in a sleeping bag is only to keep the air inside warm, not for softness. Cold ground can suck the heat out through the flattened underside of a bag as quickly as exposure to cold air would. For these reasons, a thin insulating foam pad (inflatable pads compress smaller, but are susceptible to leaks) is more or less necessary. They won't come close to the softness of a mattress, however. If you will be using it in winter, a thin one will not suffice: make it two, or invest some money – or use a thick layer of twigs, where available. Instead of a pillow, try wrapping the clothes you aren't wearing in a towel, or your sleeping bag's stuff sack, and rest your head on that. Or buy a travel pillow, which collapses into a tiny pouch.

Lodging

Some backpacking areas have shelters along the trails, spaced at intervals a typical hiker can cover in a day. If these are available, and the park authority lets you reserve them, you may be able to dispense with carrying a tent. This doesn't mean you can use a lightweight indoor "slumber party" sleeping bag, though; even when these shelters are fully enclosed, they probably won't offer much protection from cooler night-time temperatures.

In areas with extreme temperatures there may be huts or shelters with stoves or fireplaces, enabling you to have a more comfortable temperature at night – but heating the hut takes time, and in these areas there is often a risk of snow storms or other circumstances that may hinder you from reaching the shelter as planned. At least you will be able to dry your equipment there afterwards. Some know-how about handling a wood fired stove (or whatever is used in the area) may be needed. Check the condition of the stove before using it.

Camping

Tents are available in many shapes, sizes, and levels of protection. Some models (especially domes) can be free-standing, requiring no stakes to hold them in shape. But they tend to be heavier, and trickier to set up. Unless you're sure you're never going to get rained on, a tent with a "rain fly" – a water resistant raincoat for your tent – is essential (this is integrated in some tents). Check how to set up the tent in a heavy rain without the inside getting wet. This is easier with some tents than with others. Also, some tents are more dependable in high winds than others.

At the small end of the scale is the "bivy sack", which is little more than a raincoat for your sleeping bag; the most spacious ones are just big enough inside to carefully roll over. Important: a bivy bag is usually almost airtight and can cause suffocation if closed completely. Additionally, a bivy bag does not allow for drying anything, like a regular tent. Since it is so small condensation from your breath will build up. If you cannot get it dry in the day, your next night will not be too nice. Bivy bags are therefore great for shorter trips or if you are comfortable that the weather or area will provide some opportunities for drying, and are significantly lighter than even the smallest tent.

A typical "1-person" tent might give you enough room inside to actually hunch over and maybe even scrunch up and turn around, but no more. A "2-person" tent is going to be big enough for just that: two people, lying right side-by-side. Depending on just how close you and your camping partner want to be, you might prefer a "2-to-3-person" tent (otherwise big enough for two adults and a child). If you're thinking of a larger tent so you can keep your gear with you (whether for easier access or to keep it out of the weather), a tent with a vestibule or an extended rain fly might be all you really need. By the time you get to a "4-person" tent, you're generally talking about something spacious enough that one or two people can sit upright in it, but heavy enough that you'll want to distribute the components among the people in your hiking party.

Although tents will keep most of the wind out, and usually trap air well enough to keep it warmer than outside, don't count on them to keep you warm; that's your sleeping bag's job. The difference between a 3-season tent and a 4-season tent isn't their warmth, but the latter's ability to stand up to stronger winds and snow. Using a gas powered lamp can also help to warm up your tent, but beware of setting fire to your tent or melting something as the lantern casings get extremely hot.

Backcountry

If you're travelling in an area without established campsites, you should always follow leave-no-trace camping principles for making and breaking camp, as well as your other activities in the wilderness.

Things to consider when choosing site for the night vary from place to place, but may include having shelter from strong winds, keeping an eye out for dead branches hanging above your tent (widow makers), having potable water in reach and being away from irritating (mosquitoes) or dangerous (hippos) wildlife. See wild camping for some more considerations.

Stay healthy

Blisters

Take care of your feet: they're what's getting you home. If you start feeling "hot spots" on them, take care of them quickly before they develop into blisters. Moleskin offers the best protection, but if you don't have that, adhesive bandages or even tape will help protect these spots from friction.

Sunburn

Be aware of Sunburn and sun protection. You don't need to be sunbathing to need sunscreen. You'll be sweating, so apply waterproof "sport" sun lotion to anything that the sun can reach. A hat with a brim reduces the UV exposure further, and is essential if you have thin hair. Thin, light-colored clothing often seems comfortable on a hot day, but it provides very little protection against the sun. Your favorite old T-shirt has approximately the protection value of SPF4 sunscreen, which is next to nothing. If you don't want to buy and wear tightly woven clothes with a high UPF rating on a hot, sunny day, then smear sunscreen under your clothes, too. Give your skin a break during the peak hours of sun by seeking shade.

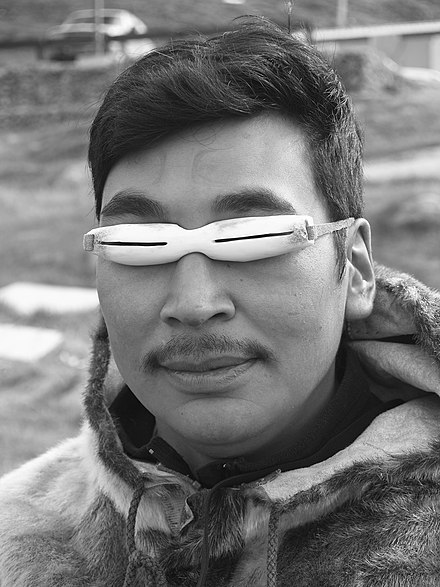

If you move over snow or ice, you should beware of snow blindness. You can avoid staring at the sun, but you can hardly avoid watching the snow-covered ground in front of you. Snow, ice, water, white sand, and any other shiny surface can reflect the sunlight up onto your skin to give you sunburn, and into your eyes to give you snow blindness, which is essentially a sunburn on your eyeball, and which can cause temporary blindness as well as pain. To reduce your risk of snow blindness, when you are around snow or other risky conditions, always wear sunglasses that block 100% of UV rays and have a wrap-around shape to keep light from entering through the sides. (You could also try the Inuit solution of a screens with very narrow slits to look through, or, in an emergency, cut a single slit, just as narrow as a knife blade, in a stiff piece of cardboard, and hold that up to your face to block nearly all of the light.) If your eyes start hurting or feeling like they have sand in them, then you should take action without delay, even to the point of covering one or both eyes entirely while you move into a safe, shaded area. The onset of pain generally indicates that your eye has already been sunburned for the last several hours, and even a small amount of further damage may result in an intolerable situation.

If you move over snow or ice, you should beware of snow blindness. You can avoid staring at the sun, but you can hardly avoid watching the snow-covered ground in front of you. Snow, ice, water, white sand, and any other shiny surface can reflect the sunlight up onto your skin to give you sunburn, and into your eyes to give you snow blindness, which is essentially a sunburn on your eyeball, and which can cause temporary blindness as well as pain. To reduce your risk of snow blindness, when you are around snow or other risky conditions, always wear sunglasses that block 100% of UV rays and have a wrap-around shape to keep light from entering through the sides. (You could also try the Inuit solution of a screens with very narrow slits to look through, or, in an emergency, cut a single slit, just as narrow as a knife blade, in a stiff piece of cardboard, and hold that up to your face to block nearly all of the light.) If your eyes start hurting or feeling like they have sand in them, then you should take action without delay, even to the point of covering one or both eyes entirely while you move into a safe, shaded area. The onset of pain generally indicates that your eye has already been sunburned for the last several hours, and even a small amount of further damage may result in an intolerable situation.

Pests

Mosquitoes, flies, and other pests can carry various unpleasant diseases; they can also be detrimental to your mental health. Mosquitoes in particular are most common around water (where they breed), in the evening twilight, and in heavy woods that resemble twilight. Most backpacks and some clothing should be treated with insecticide. Liberal application of DEET-based insect repellent is another good defense against mosquitoes, ticks, and some other insects. But even this won't stop them from swarming around you and in your face; a head net (best worn over a hat with a brim) provides a small DMZ that may help with your peace of mind, and is small and light enough to be packed "just in case".

If your personal vision of hell is mosquito bites on sunburned skin, then consider using a combination mosquito repellant and sunscreen lotion only if you will be outside for two hours or less at a time. Many sunscreens actually make DEET more rapidly effective, but the re-application times for sunscreen and all but the weakest insect repellants differ, you may not need insect repellant all day long, and you should avoid putting DEET-based products on sunburned skin – which means no more sunscreen, either, if you only have the combination product with you. In the end, packing separate bottles for bug repellant and sunscreen will give you the most flexibility. When it's time, just layer one on top of the other, and re-apply each as directed.

Killing pests, especially with non-degradable pesticides, isn't really compatible with leave-no-trace hiking. Unless you need to protect yourself from real danger, such as malaria, you should try to get by with appropriate clothing (suitable footwear, long sleeves and a mosquito hat), and save the chemicals for the times you really cannot stay sane without them.

Poisonous plants

Know and be able to identify the poisonous plants that may be in the area you will be exploring and understand basic treatment and symptoms.

Medical supplies

You don't want to go overboard with medical supplies, but a basic first aid kit is a worthwhile precaution. If you're lucky, it'll be the one thing you brought that you didn't "need", but if you're not so lucky, then you'll definitely regret leaving the essentials behind. Adhesive bandages, disinfectant, and a general-purpose headache or inflammation remedy – aspirin or ibuprofen are okay in most areas, but if dengue fever is a risk, carry paracetamol (acetominophen) instead – are the bare essentials. As makeshift bandages (and dozens of other uses), cotton handkerchiefs are worth carrying.

Many travellers carry hand sanitizer and a remedy for diarrhea as well. See altitude sickness and sunburn and sun protection for additional things needed in some areas.

Facilities

Even if there are maintained outhouses along the trail (again: don't assume there will be), you shouldn't count on them having toilet paper; bring a partial roll from home. If you're unsure about the availability of facilities, bring a garden trowel so you can dig and then cover your own single-dump latrine (well off the trail and far away from any water supplies).

Take care of your hygiene. Although you shouldn't worry too much about your natural scent, you don't want your private parts or feet to get sore, and you definitely don't want infections or an upset bowel. This applies double in cold weather, when washing is more difficult. In summer, fine sand in your socks may be an issue. Warm water is needed mostly for comfort, but you probably want a small piece of soap for your hands, and you might want a setup that allows your doing some washing a distance from your water source, and without risking the cleanliness of your cooking utensils.

If you pass by campsites or lodges with electricity, you might be able to get a shower, which can do wonders after hard days – but don't expect showers at campsites on backcountry trails, and don't expect such lodgings there. However, in some parts of the world, there may be a sauna even at some very remote and primitive huts. The sauna bath does even more wonders than a shower. Make sure you know how to handle the stove and how to dry the sauna afterwards; never use sea water on the stove. Washing in rivers and lakes, try not to get dirt or soap into the water, do that kind of washing at a distance from the shore.

Altitude sickness

Altitude sickness can be a life threatening issue when camping a high altitudes. Be aware of symptoms and treatment.

Stay safe

Dangerous animals

See the dangerous animals article for information on avoiding and dealing with a variety of animals that might be encountered in the wilderness. In many places these pose little real threat to backpackers, but some – a human-fed bear in a national park, a cow moose protecting her calf, a hungry panther, or a venomous snake – may be quite dangerous. Check with local wildlife experts about what to be wary of, and how to protect yourself.

Phones and beacons

If there's mobile-phone service in the area you're hiking (and don't assume there will be), bringing the phone along (turned off, to preserve both the battery and the atmosphere, and in a watertight package) is a reasonable precaution in case of emergency. If you get a signal in a remote area, the dispatcher that happens to pick up your emergency call may have no idea where you are, so explain clearly. Check in advance what directions would be easiest for them to recognise. WGS84 coordinates (used by GPS) are recognised in many areas, learn how to get those from your map. In some regions, the coordinates on the map may differ significantly from what your GPS tells.

There are also 406 MHz GPS Personal Locator Beacons, which when activated send an emergency signal via satellites to the rescue authorities. These are reasonably lightweight, waterproof, strobe-equipped units, a little larger than a cell phone. They cost around USD 300–400, with no subscription fees.

Weather

See also: Severe weather

Weather conditions can change very quickly at high altitude. Consult a weather forecast before departing, but be ready for anything, including fog, storms and cold weather. Also in low terrain, being prepared for adverse weather is important. Heavy rain, here or upstream, can make fording problematic. Rain and wind can cause hypothermia even in quite warm conditions.

Rain and cool weather often have severe effects on the morale of the party. Remembering warm drinks, activities and keeping a cheerful spirit can make the difference between a miserable hike and a tough one to be gilt in your memories – in extreme conditions even between life and death.

Thunderstorms cause significant hazards for hikers, including lightning strikes and wind downbursts which can topple trees. Get familiar with signs of a developing storm, such as large build-ups of Cumulonimbus clouds (“cotton ball” clouds, especially those with and flattened or “anvil” shaped tops), a sudden reversal in wind direction, a noticeable rise in wind speed, and a sharp drop in temperature. Heavy rain, hail and lightnings can occur in the mature stage of a thunderstorm. Get out of high and open areas if a thunderstorm is approaching. Do not take cover under high trees, which may get hit. Also avoid narrow river valleys, dangerous in case of flash floods.

During an intense thunderstorm, or if you cannot avoid open landscape, use the following guidelines:

- Do not lie down, the best position is sitting on a day-pack (only those without metal frames or components) or crouching with feet close together

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground, if possible; but, if necessary, keep feet and buttocks close together

- Avoid grouping together — keep a minimum of 15 feet (5 metres) between people when possible. Wide, open spaces are better places to shelter than trees or near clumps of trees. A forest may be a better place than open terrain where you are the highest object, though. Ridge tops or other high places should be avoided.

If you feel the hair on your arms or head “stand up,” there is a high probability of a lightning strike in the vicinity. Crouch or sit on a day-pack (without metal frame)

Snow storms reduce visibility to near nil. When there seems to be a snow storm approaching, head for shelter or prepare a shelter where you are. If the storm hits you, wait it out. Advancement will be very slow and the risks of frostbite, hypothermia, getting lost, losing things and getting hurt in rough terrain are big.

Even light fog or snowfall obscures distant landmarks. Check your exact position in time and use landmarks you are sure to recognize and not to miss (did you check the declination? did you check there are no magnets in your gear?). If you are not sure to find your way, wait it out.

See also

General

Different regions

- East Sussex Footpaths (England)

- Grande Randonnée (western Europe)

- Hiking and backpacking in Israel

- Hiking in South Africa

- Hiking in the Nordic countries

- Hiking and bushwalking in Australia

- Hiking in the United States

- Long distance walking in Europe

- Tramping in New Zealand

- Trekking in Nepal

Related: Urban backpacking

Related: Leave-no-trace camping

Related: Packing for a week of hiking