In the Nordic countries of Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden there are large sparsely populated areas suitable for wilderness backpacking and multiple day lodge-to-lodge hiking, and areas for day hikes even near most towns and villages – in Norway including hikes to high summits. There is a rich variety of landscapes in the Nordic countries, from volcanic Iceland to the eastern forests in Finland, from the alpine mountains of Norway to the gentle lowlands of Denmark and southern Sweden. The freedom to roam, also called right to access or, in Swedish/Norwegian/Finnish allemansrätten/allemannsretten/jokamiehenoikeus ("every man's rights"), gives access for anyone to most of the nature.

In the winter, which may mean from January to February or from October to May, depending on the destination, cross country skiing is the way to go, at least for longer distances in many areas – wilderness backpacking and back-country skiing are more or less considered the same activity. At destinations with hiking trails, there are often skiing tracks in the winter.

Some of the advice below is also relevant for other ways to explore the natural landscape.

For Faeroe Islands, Greenland and Svalbard, see their main articles.

While wilderness areas in Denmark are very small compared to other Nordic countries, the country still has some opportunities for outdoor life. See Primitive camping in Denmark.

Understand

Norway, Sweden and Finland together cover an area of well over one million square kilometres, ten times wider than Austria and Switzerland combined. The hiking area includes the humid, mild Atlantic fjords and coasts of Norway, through the wild alpine high peaks of the Scandinavian mountains, to the wide plateaus and deep forests of the interior.

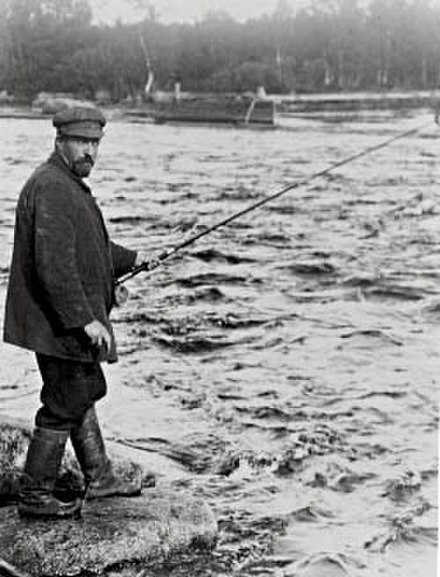

Only a few generations ago most people in the Nordic countries lived in the countryside. With a sparse population and meagre fields, forestry, fishing and berry picking gave important supplemental income to many. Today, hiking, fishing and berry picking are essential parts of the vacations for many of the local people, mostly as pastimes at the summer cottage. Not everybody is a serious backcountry hiker – but there are quite a few.

One aspect of the Nordic outdoor tradition, hunting, is strange for many who have never done it or seen someone else doing it in their life; or they are from countries where this was something reserved for the upper class. In the Nordic countries the woods have always to a large part been owned by the farmers and these have had hunting as a sometimes important complementary source of food. In the countryside being part of the local hunting club is normal. The Finnish word for wilderness, erämaa, also means hunting and fishing grounds. In old times people would go trekking precisely to get food and furs, and hiking includes traces of this tradition, at least for some hikers.

Even the remote areas are seldom truly untouched. In the north most areas are used for reindeer husbandry. Most unprotected forest is used for forestry. In practice, most people will notice this only occasionally.

Because of the sparse population, especially in the north, trails will be quite quiet, other than near the main tourist resorts. Outside trails you will see few people even near cities. Near main roads you may hear the traffic, but in the more sparsely populated areas you will only hear silence, as soon as you get away from the thoroughfares.

Climate and terrain

Type of terrain and weather conditions vary hugely, from the steep mountains of Norway to the almost flat plains of Finnish Ostrobothnia, from the moderate and rainy climate of the Atlantic coast to the nearly continental climate of inland Finland and from warm temperate climate in the south to glaciers in the mountains and tundra in the very north.

Less than 5 % of the land area of Norway is developed (farmland, roads, cities), and the proportion is similar in the other countries. In Norway, about 50 % of the area is some kind of open space without forest, including solid treeless ground and bare rock, more than 30 % is forest and about 5 % is wetland and bogs (particularly in East Norway, Trøndelag and Finnmark), 5 % is freshwater (rivers and lakes) and 1 % is permanent ice or snow. In Finland, 70 % is forest, while the open space consists mostly of lakes and bogs, in the very north also large fell heath areas. Also in Sweden wetlands are common (about 20 % of the area). About 63% of Iceland is barren landscape, 23 % has vegetation of some kind, 12 % is covered by glaciers and 3 % are lakes.

Weather forecast services are generally of good quality, but local experience may be needed to interpret them: wind conditions vary depending on local topology and for temperature only average day maxima are told in many forecasts, variation and night temperatures have to be deduced. There are many weather apps and online weather sites – but while many weather services pretend to give forecasts for any location, they don't really have a detailed enough model for that, they just interpolate from the general model. Wind is generally stronger in the high and barren mountains and along the outer coast. Difference between maximum and minimum temperature a given day is normally in the range 3–15°C (5–30°F), unless there are significant weather changes. A clear sky will usually mean a cold night. Average maximum day temperatures in July range from about 15°C (60°F) to about 23°C (75°F) depending on location, in January from about freezing to about -10°C (15°F), high mountains not counted. Temperature extremes can vary from +35°C (95°F) in the summer to -50°C (-55°F) in the northern inland winter.

Weather forecast services and information about the climate are available for Finland from the meteorological institute (smartphones) or Foreca, for Norway from the Meteorological office and weather news and for Iceland from Icelandic meteorological office.

The area is in the border zone between the Westerlies and the Subarctic; the weather can be dominated by a certain weather system or there may be hard to predict alternating weather. Near the Atlantic coast (i.e. in Iceland and in and near Norway) and at high altitudes quick changes in weather are common.

High mountains and glaciers are difficult to visit some times of the year. When judging the altitude, remember that the tree line can be at well under 400m in the northernmost parts of Finland and Norway. In Norway's and Iceland's high mountains snow can remain after winter through June, and large patches can remain all summer. On foot, Norway's high mountains can generally be visited only second half of summer and early autumn (typically July through September, visitors should get specific information for each area).

The surface in the high mountains is mostly very rugged, often loose rocks, boulder, snow and glaciers – hiking is usually strenuous and good boots are needed. This rugged, barren surface appears at much lower altitude in Norway than in continental Europe or in US Rockies; even at 1000 to 1500 metres above sea level there are high alpine conditions with hardly any vegetation and snow fields remaining through summer.

At lower altitudes, but above the tree line, there is often an easy to walk fell heath. This is the typical terrain in the "low fells" (lågfjäll), such as in the very north of Finland and between the high mountains and the forests in Sweden. Wet terrain near the tree line is often thickly covered with willow (Salix) shrubs, quite onerous to get through. Valleys are often forested, primarily with fell birch, but also some spots with pine and a bit lower still, pine and spruce forests.

The pine and spruce forests are the westernmost part of the great North Eurasian taiga belt. The taiga belt covers most of Finland and Sweden and parts of Norway (particularly East Norway and some border regions). In lowlands, especially in some parts of Finland and Sweden, there are also vast mires and bogs. The ice age left eskers, which give the landscape a peculiar rolling character in some regions. Much of southern Finland and Sweden were under the sea level when the ice left, and the bedrock is often visible even on low hills, with trees growing where enough soil has accumulated, giving a sparse forest on the hilltops. Except for some regions, only a minor part of the land is farmland. Forest dominate, although much of it is used for forestry, with many clearings. Old forest is found here and there, saved by difficult terrain, and larger areas far enough from roads and rivers.

Elevations and landforms

The highest altitudes are in the western sections of the Scandinavian peninsula from the very south of Norway, through central Norway and border regions with Sweden and until Troms and Finnmark counties in the very north. These elevations are often referred to as the Scandinavian mountains. The highest summits are in Norway's Jotunheimen, where the highest peak is 2469m. Some 200 peaks in Norway are above 2000m – mostly in Jotunheimen but also in Rondane and Dovrefjell. Sweden's highest peaks are in Lapland near the border with Norway, with a handful of peaks above 2000m. Iceland's highest peaks are in Iceland's interior and South Iceland, with one peak above 2000m. Lowlands in Norway are largely limited to valleys and shores. In general, the higher altitudes also means the wildest terrain, particularly along Norway's Atlantic coast with immense fjords (such as Sognefjord) and towering peaks rising directly from the ocean such as in Lofoten. There are however some high elevations with more gentle landforms (high plateaus), such as Hardangervidda plateau, Dovrefjell, long stretches of uplands between the great valleys of East Norway, and Finnmarksvidda (interior Finnmark plateau). Because of the colder climate in the very north, Finnmarksvidda and other elevations in Finnmark are rather barren even at just 300 to 500 metres above sea level.

Unlike the western section, Finland is characterised more by gentle landforms with forests or open ranges. Finland's highest elevations are about 1300m only, and mountains higher than 1000m over the sea level can be found only in Finland's "arm" in the extreme north-west. Save for a few exceptions in the east, you will seldom encounter mountains higher than 300m south of Lapland. On the other hand, much of Finland is covered by lakes and streams.

Compared to Finland, Sweden is hillier and much of what's north of the Stockholm–Oslo line is forested wilderness without any major cities. Finally Scania, the southernmost part of Sweden, reminds more of Denmark, the Netherlands or northern Germany — it is basically flat as a pancake, and much of it is farmland.

Iceland is similarly barren as Norway. Iceland's highest elevations are in Iceland's interior and in the Tröllaskagi mountain range in North-Iceland. Elsewhere in Iceland elevations are lower than 600 meters.

Mountains

In Norwegian, "mountain" ("fjell") mostly refers to elevations reaching above the tree line. Less steep, relatively level, treeless plateaus without pronounced peaks are often called "vidde" (the list below on partially includes such plateaus as for instance the wide Finnmarksvidda of the north).

The Scandinavian mountains can roughly be subdivided as on the map.

- A & B: Arctic mountains

- including Kebnekaise, Sarek nationalpark, Lyngen alps, Lofoten, Svartisen glacier, Narvik, Käsivarsi Wilderness Area

- C: Central border highlands (Norway and Sweden)

- D: Fjords range

- including Sunnmøre & Romsdal alps, Jostedalsbreen glacier, most of Sognefjorden

- E: Central mountains

- including Rondane-Dovrefjell, Jotunheimen (highest in the Northern Europe)

- F: Southern highlands

- including Hardangervidda plateau and Rogaland/Setesdal moorland

Seasons

The summer hiking season is generally mid May to early September, except in the north and in high mountains, where it begins in June, even in July in some areas. Hiking is mostly easy in these times and there is less need for preparations, skills and gear than other parts of the year – but some destinations are still demanding. Most of the summer mosquitoes and midges are a nuisance in many areas, especially below the treeline in the north from late June to August. In August, late evenings are starting to get dark, children return to school and some tourist facilities close for the winter.

Early autumn (mostly September) is the time of ruska, when leaves are turning red and yellow, an especially beautiful sight in Lapland and Finnmark (but the period is often short there – winter can come early). Many locals go out to pick mushroom and lingonberry. This is often a nice hiking season; days are generally mild, although frosts may be appearing at night and the first snowfalls may be appearing late in the month. Insects are largely gone and the air is usually crisp. Late autumn (October–November), on the other hand, is not the best season for most visitors: it is dark and wet, with the odd snowfall but no reliable snow cover (ski resorts do open, but often depend on artificial snow). In November the temperature sometimes drops to -15 °C or less even in southern Finland.

In midwinter there is no sunrise at all in the north – and there can be extreme cold. Days are short also in the south. You might want to experience the Arctic Night or Christmas in the homeland of Father Christmas (Finns believe he lives in Lapland and hordes of Brits are coming to visit him). Otherwise you might prefer February in the south or early spring in the north for any winter hiking. If you are going to use ski resort facilities, note the peaks at winter vacations; you may get bargains by some timing. See also Winter in the Nordic countries.

Spring is a much loved season by many locals. Days are light, the sun is strong and nature is awakening. Wilderness hikes can be demanding, with deep snow here and bare ground there, and much water, but many destinations are unproblematic. In the north and in high mountains June is still a time of melting snow and high waters in the streams and in the high mountains snow may persist into July or later. Rotten snow and high waters make hiking difficult in the affected areas in what is early summer elsewhere. Later the remaining snow is often compact, hard enough to walk on.

Spring is particularly late in the high mountains of Norway, even in June some areas are accessible on skis only. This is true in mountains such as Norwegian Jotunheimen and Hardangervidda, where snow may persist through June and large patches of snow may remain through late summer. Even in Finland there is a Midsummer skiing competition (at Kilpisjärvi). Norwegians do hike by foot carrying their skis to areas where they can continue by ski.

Freedom to roam

Main article: Right to access in the Nordic countries

In the Nordic countries there is a concept of Everybody's Rights to enjoy undeveloped land regardless of ownership, locally known as allemansrätten, allemannsretten, almannaréttur or jokamiehenoikeus. This "right to access" or "freedom to roam", as it is known in English, mainly consists of the right to freely roam by foot, by ski or by boat, the right to stay overnight in a tent and the right to pick edible berries and mushrooms. In what non-wilderness areas the rights apply varies somewhat between countries – e.g. in Iceland entry to any enclosed area off roads requires landowner's permission – as do some details. The rights (more correctly: lack of landowner right to prohibit) are accompanied by the expectation of being considerate and do not allow for breaking specific laws, doing harm (such as walking in fields with growing crop or among newly planted trees, or leaving litter or opened gates behind) or disturbing residents or wildlife; using motor vehicles is regulated and thus not covered. You should do your research beforehand so you know what your rights are and aren't. Some details are codified in law, but much is up to interpretation and court cases are rare.

When visiting national parks and other "official" destinations, read the instructions for the specific area. Mostly the provided services (such as designated campfire and camping sites) compensate for local restrictions. You are encouraged (sometimes mandated) to follow the trails, where such are provided.

Fire

See also: Campfire

You should always be careful when making a fire – make sure you know what that means. It should always be watched and carefully extinguished. In particular the spruce, which is widespread in the Nordic countries, creates a lot of flammable material. Use designated campfire sites when possible. Do not make fires on rock (which will crack) or peat (which is hard to extinguish reliably). In Sweden you need no permission, as long as you are careful. In Iceland fire is permitted outside protected areas where there is no risk for wildfire or other damage (but firewood is scarce). In Norway, making a fire is generally forbidden from 15 April to 15 September, except at generously safe distance from forest, buildings and other flammable material or on officially designated sites. In Finland open fire always requires landowner's permission, but in the north there is a general permission for much of the state owned land (check the areas covered and the terms). Being allowed to make a fire does not necessarily imply a right to take firewood; do not harm trees or aesthetically or ecologically valuable logs. In Iceland wood is an especially scarce resource and what would pass as formally not allowed but doing no harm (and thus accepted) in the other countries could definitively be bad there. In emergencies you use your own judgement.

In particularly dry circumstances, there may be a total ban on any open fire outdoors (including disposable grills and similar). In Finland such bans are common in the summer, advertised by region (in Lapland: by municipality) in most weather forecasts as "warning for forest fire" (metsäpalovaroitus/varning för skogsbrand). In spring there may be a warning for grass fire, which is not as severe, but still worth noting. Camping stoves are not regarded open fire, but they are often quite capable of starting a wildfire, so be careful with them (and with your used matches). In Sweden the bans are not centrally advertised; the bans are decided by the emergency services, usually on regional or municipal level.

In national parks and similar there are campfire sites with firewood provided for free. In some large national parks and wilderness areas making fire may be permitted where there are no campfire sites nearby (check the rules for the area). Do not make excessively big fires, but use firewood sparingly. If some of the firewood is ready-made and some not, or some is outdoors, new firewood should be made and taken indoors instead of what is used. You should usually not replenish from the nature. There is often an axe and perhaps a saw for the purpose, especially at more remote places, but you might want to carry your own. A good knife is basic survival gear and should be carried on any longer hike, as should matches, with waterproofly packed spares.

To make a fire in difficult conditions, some of three kinds of tinder is usually available in the forest: dead dry twigs low on spruce trees (only take those easy to snap off – the spruce easily gets infected), birch bark (not bark resembling that of other trees) or resinous pine wood. The three require different techniques, so train somewhere where taking the material does not harm, before having to use them. Using the spruce twigs you need enough of them, with enough fine material, and the right compromise between enough air and enough heat (you might need to use your hands; you should respect the fire but not be frightened). Using birch bark is easy, but check how it behaves. A knife is useful to get it off the wood in bigger pieces. For pine the key is to have fine enough slices. Pine usable as tinder is recognized by the scent at a fresh cut and by it being long dead but not rotten, often as hard parts of an otherwise disintegrated moss covered stump (train your eye!). In the fell birch forests, where there is no dry wood, the birch wood should be split into thin enough pieces, and made extremely thin to get the fire going (thicker firewood can be used to keep mosquitoes at bay, and after it having dried enough). Above the tree line you can use dry twigs, but getting enough dry firewood can be difficult.

Light

Due to the northern latitude, the sun wanders quite near the horizon both day and night much of the year. Twilight lasts much longer than nearer the equator, for more than half an hour in the south and possibly for several hours in the Arctic Night (with no daylight).

Daylight is limited in late autumn and early winter, and hours available for hiking are very limited at least in dense forest, in rough terrain and where orienteering is difficult, especially as the sky often is cloudy in late autumn. In winter the snow will help even the stars to give some light in the night, which may be enough in easy open terrain once you get used to it – moonlight may feel plenty.

From May to July nights are quite light throughout the region. There is Midnight Sun for a month and a half in the far north and only a few hours of (relative) darkness even in the south around Midsummer. By August, nights are getting dark and in late autumn, before the snow comes, there are very long dark evenings.

Be aware that sun rays can be extremely strong in summer at high altitudes because of clean air, reflections from lakes and snow fields, and little vegetation.

People

.jpg/440px-Amanda_Delara_(29519019388).jpg)

Staff at any information centre, hotel etcetera are usually fluent in English and information aimed at tourists is mostly available also in English. At large tourist attractions, hotels and the like there is usually personnel fluent in several languages, but in family businesses elderly people are not necessarily fluent except in their mother tongue. You will mostly be able to survive on English, though – and you may meet a Sami born in a goahti but speaking several foreign languages fluently.

The north of the Scandinavian countries is the homeland of the Sami people; they are the majority in a few municipalities and big minorities in others. Because of the language politics half a century ago, many Sami do not speak Sami, but many do, especially in northernmost Finnish and Swedish Lapland and most of Norwegian Finnmark. They also speak the majority language of the country and by the borders, possibly the language of the neighboring country (Swedish and Norwegian are also mutually intelligible). There are large groups speaking Finnish dialects (Meänkieli, Kven; in addition to the majority language) in the Swedish Tornedalen and in parts of Finnmark.

In the archipelago of Uusimaa, the southern Archipelago Sea, Åland and the coast of Ostrobothnia Swedish is the traditional language. You will survive on Finnish or English, but the Swedish-speaking people may not be very impressed by your trying to greet them in Finnish.

In some of the sparsely populated areas, such as Lapland and the Finnish archipelago, tourism is an important supplemental income for many. Small family businesses do not necessarily advertise on the Internet or in tourist brochures. You have to keep your eyes open and ask locally.

Destinations

See also Hiking destinations in Norway and Finnish national parks.

The freedom to roam allows you to go more or less anywhere. There are forests or other kinds of nature open to the public in all parts of the countries. Those who like wilderness backpacking or want to be off roads for several days might look for the least populated areas, such as in the northern inland of Finland, Norway and Sweden, in or just east of the central Norwegian mountains (Jotunheimen, Hardangervidda, Dovre), in eastern Finland and in Iceland's interior. In some places you can walk a hundred kilometres more or less in one direction without seeing a road.

In Norway, there are trails for day hikes or longer treks all over the country. In the other countries there are also undeveloped areas everywhere, suitable for a walk in the wood or for picking berries, but for trails or other routes suitable for a longer trek you usually have to study the map a little more, or travel some distance to a suitable trailhead.

Note that wilderness backpacking in the Nordic countries can mean hiking without any infrastructure whatsoever, possibly not meeting anybody for days and being on your own also when something goes wrong. This is something many people come for, but if you doubt your skills, choose appropriate routes. There are all levels of compromises available.

The best hiking or scenery is not necessarily in national parks or nature reserves. It may, however, be worthwhile first considering "official" or otherwise well-known destinations, which cover some of the most valuable nature and some of the finest landscapes. It is also easier to find information and services for these.

Protected areas of different types are sometimes intermingled with each other. There may, for example, be areas with severe restrictions inside a national park or a less restricted boundary zone outside the park. There are also protected areas that have little influence on the hiker, restricting mainly actions of the landowner and the planning authorities.

In Finland, national parks, wilderness areas and some of the other destinations are maintained by Metsähallitus, the Finnish forestry administration, which has information about the destinations and hiking in general on nationalparks.fi. Information is also provided at their customer service points and national park visitor centres, where you might be able to reserve a bed in a hut or buy fishing (or even hunting) permits. Also Finnish National Parks has information on most "official" destinations.

In Norway, the Trekking association maintains trails between their many huts (mountain lodges) in all parts of the country.

National parks

In Norway, "national park" primarily denotes protected status for undeveloped area. Hiking and scenery is often equally nice outside parks. National parks are often surrounded by a zone of "protected landscape", which from the hiker's point of view often is the most interesting and usually the most accessible wilderness.

Otherwise national parks are the most obvious destinations. They cover especially see-worthy nature, services are typically easily available and most are reachable without much fuss. There are usually shorter trails near the visitor centres, suitable to quickly see some of the typical nature, for day trips and for less experienced hikers. In the larger ones there are also remote areas for those wanting to walk their own paths. Contrary to practise in some other countries, national parks do not have roads, fences or guards – in Norway only trails and lodges.

There are national parks throughout the countries, covering most types of wild (and some cultivated) landscapes: Finnish National Parks, Swedish National Parks, Norwegian National Parks, Icelandic National Parks (dead link: January 2023).

The visitor centres ("naturum", "nasjonalparksentre"), sometimes quite a distance from the park itself, often give a useful introduction to the nature and culture of the area. There may be films, guided tours or similar, worth checking in advance. Some of the centres are closed outside season or not manned at all.

Recreational areas

Recreational areas are often more easily reached than national parks and may have fewer restrictions. Many of them are suitable for hiking, although they are smaller than most national parks and seldom offer the most majestic scenery.

In Finland National Hiking Areas are maintained by Metsähallitus.

Most towns have at least some recreational areas, usually reachable by local bus or by a walk from the town centre. There are extensive hiking possibilities outside some towns. For instance around Oslo there are wide forests with well-maintained trails or paths (some with lights) within reach of metro and city buses, and within Bergen there are several mountains next to the city centre.

There are hiking and skiing routes around most ski resorts and similar. Sometimes they connect to national park trail networks.

Nature reserves

Nature reserves generally have the most strict form of protection and rules for the specific reserve should be checked in advance. They are created to protect the nature, for its own sake and for research. Usually there are hiking trails through the bigger ones and there may be some lodging or camping facilities outside the protected area. They may encompass very special or well preserved nature. They are mostly smaller than national parks and (those with trails) usually suited for a day trip or one day's hike. Deviating from trails is often allowed in wintertime or outside the nesting season.

Wilderness areas

Wilderness areas in Finland are remote areas defined by law, with severe restrictions on building infrastructure or any exploitation other than for traditional trades (such as reindeer husbandry, hunting or taking wood for household needs). The status has little direct impact on a hiker, but they are interesting destinations for those that do not want ready made trails. The areas are important for reindeer husbandry, there might be fishers, but mostly you will be alone, possibly for days. There are some trails and wilderness huts in the areas and there are usually some tourist services nearby. Licences for hunting small game (in season) are typically available. For examples, see Käsivarsi, Pöyrisjärvi and Muotkatunturit.

Unofficial destinations

You may hike more or less anywhere you want to. The usual reason not to use an "official" destination, is that you want to hike or roam near the place where you otherwise are staying or happen to pass by. Even near the bigger towns there is usually plenty of quite unspoiled nature. Locals often don't distinguish between "official" destinations such as national parks and other hiking areas. The freedom to roam allows you to enjoy it as long as you keep away from yards, cultivated land and similar. Be considerate and polite when you meet people and try not to disturb others.

Most of the countries (about 95% of Norway) is some kind of wilderness where the public is allowed to hike. Even in such wilderness there may be occasional roads reserved for logging, hydro power construction or power line maintenance. In Finland such roads are common in unprotected areas and provide easy access for berry pickers and hikers alike, while ruining the feel of wild nature – choose routes where the forestry roads (and clearings) are not too common. In Norway there are in addition many roads to summer farms (seter) in the forests or mountains or to abandoned farms. Such roads may not be open to public traffic and are usually dead-end roads with minimal traffic. Seters are usually hubs for hiking trails in the area.

If you go off-grid, make sure you have the needed skills and equipment; getting lost might be quite easy, and if you wander off in the wrong direction, it may take many days before you find anybody.

Hiking trails

Trails are often meant for use either in summer or in winter. When using them outside the intended season it is important to check the viability of the route. Winter routes are usually meant for cross-country skiing and may utilise the frozen lakes, rivers and bogs, while summer routes may have all too steep sections, go through areas dangerous in wintertime or simply be difficult to follow when marks are covered with snow. When evaluating the route, make sure you understand whether any descriptions are valid for the present conditions. Local advice is valuable.

Usually deviating from trails is allowed, except in nature reserves and restricted parts of national parks, although not encouraged in sensitive areas or areas with many visitors. Many experienced hikers prefer terrain without trails, at least for some hikes.

In addition to hiking trails at separate destinations there are some long distance hiking trails and hiking trail networks connecting nearby protected areas and recreational areas. They usually follow minor roads some or most of the distance, going through interesting natural surroundings wherever possible and sometimes passing by villages and tourist attractions, where you might be able to replenish. Lengths vary from suitable for a one day hike to the extreme European long distance paths. The longest routes are usually created by combining trails of different trail networks, which increases the risk of some parts not being well signed or maintained. There may even be parts missing. As hiking on other persons' land is perfectly allowed, you can make your own adjustments to the routes, but this may sometimes mean walking by a road or through unnecessarily difficult terrain.

On combined trails or trails that pass borders (between countries, municipalities or areas with different protection status), it is quite common that the markings or the maintenance standard change. Check that the same agent is responsible for the trail all the way or be prepared for it to change character. This is no problem if you have the equipment and skill to continue regardless, but can be problematic if you made your decision based on what the first part looked like. The character of the trail can change also for other reasons, such as leaving for the backwoods, reaching higher mountains or crossing mires.

In contrast to many trails in continental Europe, the hiking trails seldom go from village to village, but tend to mostly keep to non-inhabited areas. There is usually no transport (for instance for luggage) available. Where the trails follow traditional routes (from the time before the cars), they usually do so in the wilderness, where few villages are to be found. Newer trails have usually been made for exploring the natural landscape, not to connect settlements. Many trails lead from permanent settlements to shielings (summer farms, seter in Norwegian, fäbod in Swedish, karjamaja in Finnish) in the forest or in the high valleys, then onwards to pastures further into the uplands, high plateaus or high valleys. In Norway, such shielings are often starting points for hiking trails at higher altitudes, DNT lodges are often found at old shielings.

There are trails usable with wheelchair or prams, but this is not typical. Many trails follow quite narrow and rough paths. Even trails that start wide and smooth may have sections that are muddy (possibly with duckboards) or narrow, steep and rocky. This is true also for some very popular trails, such as the one to Trolltunga. Check, if this is important for you.

DNT maintains some 20,000 kilometres of summer trails in Norway. In the fells these are usually marked with cairns, some of which are marked with a red "T". In woods, markings are often red or blue stripes painted on trees. Winter routes and routes where the cairns would be destroyed in winter often have poles instead, also these usually with a red mark. Note that new or little used trails may be less worn than other paths leading astray. Winter routes are often marked with twigs instead of permanent marking, before the main season in spring. Markings in Finland and Sweden follow somewhat different standards.

The DNT trails are also classified: green trails do not require special skills and are often short (those suitable with wheelchair or pram are specially marked as such), blue trails require some fitness and basic skills, red trails require experience, fitness, good footwear and adequate equipment, while black trails can also be hard to navigate. Metsähallitus in Finland has some years ago started with a similar classification (with red and black combined and less emphasis on fitness, as the terrain is less demanding there).

In addition to the classification, DNT gives height profile and estimated time for the trails. The times are calculated for a fit and experienced hiker, excluding breaks – add considerable time to get a realistic estimate of total time needed.

There are three hiking routes in the Nordic countries that belong to the European long distance paths network (long sections are missing or unmarked at least in the Finnish parts):

- E1 hiking trail runs from Italy through Denmark and southern and middle Sweden to Nordkapp in Norway

- E6 hiking trail runs from Turkey through Denmark, southern Sweden and Finland to Kilpisjärvi (the north-west tip of Finland by the Swedish and Norwegian border). You can continue by the Nordkalottleden.

- E10 hiking trail runs from Spain through Germany and Finland to Nuorgam (the northern tip of Finland, by the Norwegian border). From Koli National Park to Urho Kekkonen National Park in Finland the route is known as the UKK route.

The Nordkalottleden/Nordkalottruta trail (800 km) goes through Sweden, Norway and Finland (dead link: January 2023) offering versatile northern fell landscape, with easy to travel fell highlands, lush birch forests, glaciers and steep-sided gorges.

The Padjelantaleden trail (140 km) and Kungsleden trail (440 km) meander through the national parks of Swedish Lappland, one of Europe's largest remaining wilderness areas. Södra Kungsleden is a 360-km trail through Sweden's southern mountain region, in Dalarna (with 180 km), Härjedalen and Jämtland, Bergslagsleden winds through old forests of the old mining region of Bergslagen. Skåneleden is a 1000-km trail all around the very south of Sweden.

Some Finnish trails are described by Metsähallitus. For trails at specific destinations, see that destination. There are also trail networks maintained or marketed by municipalities and other entities, such as the Walks in North Karelia network.

Gear

For a basic idea about what to pack, have a look at packing for a week of hiking, wilderness backpacking and cold weather. There's the challenge of packing minimally and not taking extra stuff you won't use, but on the other hand you want to be prepared. Inexperienced hikers usually pack too much, but a heavy backpack is better than missing something crucial, and going just for a few days you don't have the weight of food for a week. There are also two schools: use traditional quite heavy equipment or ultra-light high-tech; the latter is favoured by sponsored hiking blogs. In any case, a versatile tool you master is better than a dozen different ones you don't know how to put in good use. A good knife and a way to make fire go a long way for those who know the tricks.

Good quality hiking equipment is available in many specialist shops, and those shops should also be able to give good advice. Some equipment is available for rent at some destinations, especially if you are using a guide.

Every hiker must be familiar with the proper equipment for various seasons and areas as well as their style of hiking. In the Nordic area, choosing the right equipment may be particularly challenging outside the warmest summer and for the higher mountains.

Pack so that your spare clothes and outs won't get wet in rain and moist. Most backpacks are water repellent, but few if any are water resistant. Many have an integrated "raincoat", for others one is available as an add-on. Using plastic bags or similar inside the backpack is wise.

All year

- Map – 1:50,000 standard topographical maps with trekking info are generally recommended; 1:25,000 are available for some areas and give greater detail, necessary for hikes in forests, where sight is limited; 1:75,000 and 1:100,000 are usable for good trails but may not give enough details in rough or steep terrain

- Compass – you want robust, low-tech navigation

- First aid kit

- Bottle(s) for water – e.g. used mineral water bottles

- Sunglasses – in summer, on snow and at high altitude

- Sunscreen – particularly at high altitude and where there is sun and snow

- Sleeping bag, hiking mattress and tent – on overnight hikes, unless you know you will get by without

- Food, snacks

- Camping stove – on any longer hike

- Cutlery etc.

- Matches

- Knife – carrying a knife in a public place is illegal, unless you have a good reason, carrying it together with camping equipment is acceptable.

- Repair kit covering any essential gear (by your definition of essential on the hike in question – knife, rope and tape will get you a long way)

- Fabric in bright colour, such as a reflexive vest, to aid finding you if need be. Can be your tent, backpack or similar.

- Optional

- satellite navigator (GPS) – not a substitute for map & compass

- Mobile phone (pack watertight and keep off most of the time – the phone trying to find a base station when none really is in reach uses a lot of power). If there may be lodgings with electricity outlets, you want to bring a charger; some huts, especially in Norway, have solar power with USB outlets: have a suitable plug. If you are going to use the phone, you might want to carry extra batteries (a power pack) and perhaps a back-up charger. In a company on a long hike, you probably want to carry one phone that you don't use, to have a charged one in emergencies. It can be an old sturdy one with no SIM card.

- Binoculars

- Torch, candles: seldom needed in the white nights, but at least in autumn and winter a light source may be needed in the night; many wilderness huts lack electricity

- Towel (light)

- Nordic walking poles, a walking staff or similar, to aid in keeping the balance in rough terrain and while fording

Summer

On short hikes or in easy terrain you may get by without some of these. The right foot wear is the most important for a successful hike.

- Foot wear:

- Jogging shoes are acceptable on tractor roads and other smooth trails in the lowland

- Rubber boots are good in wet terrain, unless the terrain is too rough for them

- Hiking boots with ankle support and a sturdy sole on rougher trails and in some terrain off trails; some people prefer lighter footwear also on rough ground, do as you wish if you are sure-footed and have strong ankles

- Gaiters or tall (military style) boots useful in muddy areas, after snow fall or in areas with dense low bushes

- For steep hills, on very rocky surface, with crampons or heavy backpacks, stiff, durable mountain boots often needed

- Trousers:

- Flexible, light hiking/sport trousers in synthetic material is useful for most conditions, preferably water repellent, if you have two pairs one pair should probably be suitable for hot weather

- Shirt on body:

- Cotton or synthetic on warm days

- Wool or similar on cool days/high altitudes

- Walking staff can be useful in rough terrain and for fording, Nordic walking sticks also serve some of these needs

;In the backpack

- Mosquito repellent (for the warm season, particularly in the interior), in some areas a mosquito hat is very much recommended

- Wool underwear

- Shirt/jumper (wool or microfleece)

- Wind proof, water repellent jacket

- Raingear (on short hikes the jacket may be enough, on some hikes the raingear should be heavy duty)

- Head cover (for rain, warmth, sun and mosquitoes)

- Neck cover (in high altitude for all but the shortest hikes, otherwise probably not necessary)

- Light gloves/mittens (high altitude, also otherwise if weather can become cold)

- Light footwear for the camp (to let the foots rest and the heavy duty boots dry), possibly also for fording

Winter

Already 15 cm (half a foot) of snow makes walking arduous, and much more is common also in the south, in some areas more than two metres (6 feet) is possible. Walking is thus a serious option only around your base or camp, at much used trails (do not spoil skiing tracks!) or if you know there will be little snow. In addition, in early Winter (November-December) there is little or no daylight. On Norway's Atlantic side heavy snowfalls are common, particularly a bit inland and uphill. Several metres of snow has been recorded along the Bergen railway (near Hardangervidda). In the city of Tromsø the record is more than two meters, in the month of April, more than a metre heavy snow is common. The deep snow typical in Western Norway and Troms county is often heavy and sticky, making hiking really difficult.

Snowshoes probably work as well here as in Canada, and there are snowshoe trails at some destinations, but they are much slower than skis in most Nordic conditions.

This means cross-country skis are necessary for most Nordic winter hiking. Depending on conditions you may get away with skis meant for track skiing, but if you are going to ski off tracks, "real" cross-country skis are much better. There are many options though, mostly depending on whether you are going to mountainous terrain and whether deep loose snow is to be expected. Also check what possibly breaking parts there are, and whether the skiing boots are suitable for all conditions (warm enough etc.).

For clothing, advice for cold weather apply. You should have light enough clothing not to get too sweaty going uphill (especially important when it is cold, as you will not get dry easily), but also warm enough when having sought shelter for a snow storm.

Some portable stoves fare badly in really cold conditions. Check that for yours.

Some mobile phones fare worse in cold weather than others. Having the phone off in a sealed bag close to your body protects it and its battery, but it might still not work when needed.

When the sun comes out in earnest, i.e. after midwinter, be careful about snow blindness and sunburn. Mountain goggles are good also in some windy conditions (the snow carried by strong wind sometimes feels like needles).

Most people hiking in winter in the north or in the mountains stay overnight indoors, at wilderness huts. In severe weather it may however be hard to get to the hut, and in some areas there simply are no huts where you would need them. If you might have to sleep outdoors, make sure your equipment is good enough. Some tools for digging snow can come handy. In the south, where temperatures are comparably manageable, even quite cheap winter sleeping bags are enough, at least in mild weather or when sleeping by a fire at a shelter.

Remember that the unmanned huts are usually heated by wood, and it may be as cold indoors as outside (even colder, if temperatures have risen) when you arrive. It will take some time and labour before it gets warm – and if your matches got wet you won't be able to light the fire (unless you find some hidden away in the hut). A good knife, matches, torch and candles are important equipment.

For areas where avalanches are possible, and on glaciers, special equipment is needed.

Get in

From most towns there is some hiking terrain in reach by local bus and by foot. Here is some advice for more remote destinations, such as most national parks.

From most towns there is some hiking terrain in reach by local bus and by foot. Here is some advice for more remote destinations, such as most national parks.

By coach

There are usually coach connections with stops near your destination. Watch out for express coaches that may not stop at your stop. Connections that start as express may stop at all stops in the far north.

Some destinations do not have direct coach connections. There might be a school bus, a regular taxi connection or other special arrangements to use for the last ten or twenty kilometres.

By car

See also: Driving in Sweden

There are usually parking areas near the starting points of hiking routes in national parks and at similar destinations. You might, however, want to consider leaving your car farther away and use local transports, to be freer to choose the endpoint of your hike. On the other hand you can drive your car on minor roads without coach connections and stop at your whim – and for planned hikes you often can have a local business drive your car to a suitable location near the endpoint.

You are allowed to drive on some private roads, but not all. In Finland and Sweden roads that get public funding are open for all to use. Generally, unless there is a sign or barrier you are OK (watch out for temporarily opened barriers, which may be locked when you return). Parking may be disallowed in Norway except in designated places, in any case you should take care not to block the road or any exits. Some private roads are built for use with tractors, all-terrain vehicles or similar (or maintained only before expected use) and may be in terrible condition. In Iceland also many public roads (with numbers prefixed with "F") require four wheel drive cars and many mountain roads are closed in winter and spring.

Winter driving requires skills and experience, and should be avoided unless you are sure you can handle it. Nordic roads are regularly covered in ice, slush or hard snow during winter. Not all minor roads are ploughed in winter. In Norway even some regional roads are always closed in winter and there is a telephone service (ph 175 in Norway) to ask about temporarily closed roads and road conditions.

By boat

Some destinations are best reached by boat. There may be a regular service, a taxi boat service or the possibility to charter a boat (crewed or uncrewed).

By taxi

Taxi rides are expensive, but they may prove worthwhile to avoid hiring a car or bringing your own, and to allow you to choose starting and ending points of the hike more freely.

Sometimes there are special arrangements that can be used, such as a reduced rate or shared regular taxi service, or a possibility to use a taxi transporting children to or from school (minivan taxis are common for these services).

Although taxis in the towns are usually ordered via a calling centre, in the countryside you might want to call the taxi directly. Numbers may be available from the yellow pages of the phone catalogue, from tourist information centres, visitor centres or tourist businesses.

By train

In Norway and Sweden there are train connections to some hiking destinations. Also in Finland train can be a good option for part of the voyage. Iceland has no railways. Long-distance trains often run overnight. There may be combined tickets, where you get a reduction on ferries or coaches by booking the voyage in a special way.

In Finland trains are especially useful for getting from the south (Helsinki, Turku, Tampere) to Lapland (Rovaniemi, Kemijärvi, Kolari). The overnight trains on this route also take cars (loaded quite some time before departure, and not to all stations, check details). Nearly all trains take bikes. There is usually a smooth transfer to coaches or minibuses to get farther.

In Sweden Abisko on the Luleå–Narvik railway (Malmbanan, "Iron Ore Railway") and Porjus on Inlandsbanan provide railway access into the Laponia national park complex or nearby destinations, such as Abisko National Park, Kebnekaise and the Kungsleden and Nordkalottleden trails. Bikes are not allowed on mainline SJ trains, except foldable ones.

In Norway Hardangervidda can be reached directly from the spectacular Bergensbanen railway between Oslo and Bergen, and some stations are available by train only. The Nordlandsbanen (Trondheim–Bodø) railway runs across the Saltfjellet plateau, while the Dovrebanen (Lillehammer–Trondheim) runs across the Dovrefjell plateau. The Malmbanan runs through the Narvik mountains and passes the wild areas at the border between Norway and Sweden.

By plane

Some destinations are remote. There may be an airport near enough to be worth considering. The airport probably has good connections to the area.

If you want to spend money you might be able to charter a seaplane or helicopter to get to the middle of the wilderness – but part of the joy is coming there after a tough hike and few areas are remote enough to warrant such a short-cut other than in special circumstances. There are flights for tourists to some destinations especially in Sweden, where also heliskiing is practised near some resorts, while such flights are available but scarce in Finland, and air transport into the wilderness generally is not permitted in Norway.

By bike

Most destinations are reachable by bike. If the destination is remote you might want to take the bike on a coach or train or rent a bike nearby. In Sweden only some trains take bikes. Foldable bikes can be taken also on the others.

By snowmobile

There are networks of snowmobile routes in parts of the countries, e.g. covering all of northern Finland. Rules for driving differ between the countries. Driving around by snowmobile is forbidden at many destinations, but routes by or through the areas are quite common. Ask about allowed routes and local regulations (and how they are interpreted) when you rent a snowmobile. Note avalanche and ice safety implications and do not disturb wildlife. Maximum speed is about 60 km/h on land, with trailer with people 40 km/h, but lower speed is often necessary.

In Finland driving snowmobile (moottorikelkka, snöskoter) on land requires landowner's permission. Driving on lakes or rivers is free, unless there are local restrictions. There are designated snowmobile routes and tracks especially in the north, leading by national parks and wilderness areas. The snowmobile routes maintained by Metsähallitus ("moottorikelkkareitti", "snöskoterled") are regarded roads and thus cost nothing to use, while snowmobile tracks ("moottorikelkkaura", "snöskoterspår") require buying a permit, giving "landowner permission". Beside Metsähallitus, also e.g. some local tourist businesses make snowmobile tracks. Snowmobile "safaris" (i.e. tours) are arranged by many tourist businesses. Minimum age for the driver is 15 years and a driving licence is required (one for cars or motorcycles will do). Helmets and headlights must be used. Check what tracks you are allowed to use; driving on roads is not permitted, except shorter stretches where necessary, as in crossing the road or using a bridge. See Finnish Lapland#By snowmobile for some more discussion on snowmobiles in Finland.

Snowmobiles are extensively used by the local population in the north, especially by reindeer herders (permits are not needed for using snowmobiles in reindeer husbandry or commercial fishing).

In Sweden snowmobiles may in theory be driven without permission, where driving does not cause harm (there has e.g. to be enough snow), but local regulations to the contrary are common, especially in the north. In the fell area driving is generally restricted to designated routes. Minimum age is 16. A driving licence is needed, a separate snowmobile licence unless the licence is from before 2000 (foreigners might be treated differently, ask). Headlights must be used.

In Norway all use of motor vehicles in the wilderness is generally forbidden unless specific permission is obtained. A driver's licence covering snowmobile (snøskuter) is needed. Helmets and headlights must be used.

In Iceland driving a registered and insured snowmobile is allowed when the ground is frozen enough and there is enough snow not to cause harm. Driving in national parks and cultivated lands however is forbidden. A driving licence for cars is needed.

Fees and permits

See also: Right to access in the Nordic countries

There are no entrance fees to national parks, wilderness areas or other hiking destinations, and entry is usually allowed from anywhere. There may however be service available for a fee, such as lodging in cabins (which is highly recommended at some destinations) – and of course fees for transportation, fishing permits and the like. Many services of visitor centres are free.

In most nature reserves only marked trails may be used; entry is entirely forbidden for the public to a few nature reserves and to a few restricted areas of national parks. The rules often vary by season: more severe restrictions when birds and mammals have offspring, often April–July, or when there is no snow cover. Otherwise you are mostly allowed to find your own paths.

Picking edible berries and mushrooms is allowed even in most nature reserves, with limitations in non-protected areas varying by country. Non-edible species are usually protected in nature reserves. Collecting anything else, including invertebrates, stones or soil is usually forbidden in the reserves, often also in national parks.

Camping in nature reserves is usually forbidden, but there may be a suitable site (with toilet etc.) by the trail just outside the reserve.

Fishing

There are several systems for fishing permits. Normally you pay for a permit for fishing in general and separately to the owners of the waters or an agency representing them. Some fishing is free. Salmon waters (many inland waters in the north) are often not covered by the ordinary fees, but use day cards instead. Make sure you know the rules for the area you will be fishing in; there are minimum and maximum sizes for some species, some are protected, and there may be detailed local regulations. Note that there are parasites and diseases that must not be brought to "clean" salmon or crayfish waters by using equipment used in other areas without proper treatment (be careful also with carried water, entrails, which can be carried by birds etc.). Tourist businesses and park visitor centres should be happy to help you get the permits and tell about needed treatments.

In Finland, fishing with a rod and a line (with no reel nor artificial lure other than a jig) is free in most waters. For other fishing, people aged 18–64 are required to pay a national fishing management fee (dead link: January 2023) (2016: €39 for a year, €12 for a week, €5 for a day). This is enough for lure fishing with reel in most waters, but streams with salmon and related species, as well as some specially regulated waters (not uncommon at the "official" hiking destinations), are exempted. For these you need a local permit. Fishing with other tools (nets, traps etc.) or with several rods always requires permission from the owner of the waters, in practice often a local friend, who has a share. There are minimum sizes for some species, possibly also maximum sizes and protection times. The restrictions are published online at kalastusrajoitus.fi (national restrictions by species and local exceptions by water area), but in practice you probably have to check from a visitor centre, suitable business, local fisherman or the like.

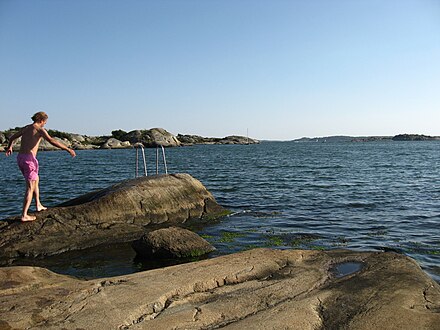

In Norway fishing with a rod and a line is free in salt water (living bait and fish as bait are prohibited). Norway's rivers and lakes are generally private and landowner permission is required. In water with salmon and related species a state fishing licence is also needed.

In Sweden fishing from the shore with hand-held tools (rod-and-line, lure and similar fishing) is generally permitted in the biggest lakes (Vänern, Vättern, Mälaren and Hjälmaren in southern Sweden, Storsjön in Jämtland) and in the sea. For fishing with nets etc. or from a boat, check the regulations. Other waters are mostly private property and a permit is required. The permits can often be bought from e.g. a local petrol station or fishing shop, for some waters also on Internet or by SMS.

In Iceland fishing does require buying an permit from the land owner. This also applies to fishing within national parks.

Hunting

The additional meat got by hunting has always been welcome in the countryside, and hunting has remained a common pastime. Especially the hunt on elk get societies together, as the hunt is usually by driving. Among city dwellers hunting can be much more controversial.

For hunting yourself, you need general hunting and arms licences, and a permit for the specific area, time and intended game. Check the regulations well in advance. Some tourist businesses arrange hunting trips. If you are going to use such a service, they can probably help also with preparation and may enable hunting without licences, under their supervision.

The licences are usually easily obtained if you have such in your home country, but regulations are strict and some bureaucracy needed. You should of course acquaint yourself with local arms and hunting law, the game you are going to hunt and any similar protected species.

The permit is usually got either as a guest of a hunting club (which has obtained rights to hunting grounds), through a governmental agency (for state owned land; Finland: Metsähallitus, mostly for the wilderness areas) or through an association administering renting of private land (common in Norway).

Big game hunting in Norway (moose and red deer) is generally reserved for landowners and most forests are private. Reindeer hunting is possible in some areas of Southern Norway, largely on government land in the barren mountains. In Finland big game (including also wolves and bears in small numbers) requires special permits, usually acquired by the hunting club in an area. You may get a chance to join, but probably not to hunt independently.

Get around

Freedom to roam is mostly about getting around by foot or ski, but you may also want to use other equipment. There are often trails but seldom roads inside the protected areas.

You are allowed to use nearly any road, also private ones, unless you use a motorized vehicle. With a motorized vehicle you may drive on most private roads, but not on all (see By car above), and use of motorized vehicles off road is restricted: usually you at least need landowner's permission. In Norway and Iceland there are also restrictions on the use of bicycles outside trails or tractor roads.

As all Nordic countries are members of the Schengen Agreement (and have far-reaching cooperation), border controls are minimal. Unless you have something to declare at customs, you can pass the border wherever – and if you have, visiting any customs office before you go on your hike may be enough. This is especially nice on the border between Sweden and Norway, on Nordkalottleden near Kilpisjärvi, where Norway, Sweden and Finland have common land borders, in Pasvik–Inari Trilateral Park near Kirkenes and (for the hardcore backcountry hiker) if combining visits to Lemmenjoki National Park and Øvre Anárjohka National Park. The border to Russia is quite another matter, paperwork is needed to visit that border area.

If you have a dog, be sure to check the procedures: there are some animal diseases that need documented checking or treatment before passing the border. In a few places, dogs may be entirely prohibited. Dogs should be on leash at all times, except where you know you are allowed to let them free. They can easily wreck havoc among nesting birds and among reindeer. In any case you must be capable of calling your dog back if it e.g. finds a wild animal, livestock or another dog.

If you are a big group, of more than 6–8, consider splitting it up at least part of the time. Big groups easily get noisy, you will see more of your fellow's backpacks than of the surroundings, and that pmartigan or capercaillie is probably seen only by those walking in front. Large parties also aren't that popular around wilderness huts, the smallest of which have beds only for four (some turf huts only sleep two). Without several experienced hikers, you cannot really split up, but in that case, camp by yourselves instead of using wilderness huts, use big enough lodges (which will be noisy anyway), or book your lodgings.

Orienteering

.jpg/440px-In_the_forest_(Troms%C3%B8,_Norway).jpg)

At least on longer hikes you will need a compass, a suitable map and the skill to use them. Official trails are usually quite easy to follow, but there might be signs missing, confusing crossings and special circumstances (for instance fog, snow, emergencies) where you can get lost or must deviate from the route. Finding your way is your own responsibility. A GPS navigation tool is useful, but insufficient and prone to failure.

Magnetic declination is roughly in the range −15° (western Iceland) to +15° (eastern Finnmark), enough that checking might be important. Finnish compasses often use the 60 hectomil for a circle scale; declination may be given as mils ("piiru"), i.e. 6/100 of degrees. One mil means about one metre sideways per kilometre forward, 10° about 175m/km. Map north doesn't have to be true north, so an additional correction may be needed for exact bearings.

As anywhere, compasses are affected by magnetic fields, and magnets have become common in clothing and gear, e.g. in cases for mobile phones. A strong magnet, or carrying the compass close to a weaker one, can even cause the compass to reverse polarity permanently, so that it points to the south instead of to the north. Check your gear.

In addition to the "official" maps mentioned below, there are nowadays those by private entities, which may choose areas to cover in a way more suitable for hikers, and may included non-official services. As much of the data is free, some map makers may publish maps without any knowledge about facts on the ground. Check that yours is from a source trusted by local hikers or do your own reliability checks.

For Finland, Maanmittaushallitus makes topographic maps suitable for finding your way, in the scale 1:50,000 (Finnish: maastokartta, Swedish: terrängkarta) for all the country, recommended in the north, and 1:25,000, earlier 1:20,000 (peruskartta, grundkarta) for the south. You can see the map sheet division and codes at Kansalaisen karttapaikka by choosing "order" and following directions. The former map sheets cost €15, the latter €12. For national parks and similar destinations there are also outdoor maps based on these, with huts and other service clearly marked and some information on the area (€15–20). Some of these maps are printed on a water resistant fabric instead of paper. For some areas there are detailed big scale orienteering maps, available at least from local orienteering clubs. Road maps are usually quite worthless for hikers once near one's destination.

Newer maps use coordinates that closely match WGS84 (EUREF-FIN, based on ETRS89), older ones (data from before 2005) a national coordinate system (KKJ/KKS/ISNET93; difference to WGS84 some hundred metres). In addition to coordinates in degrees and minutes (blue), metric coordinates are given in kilometres according to some of the old KKJ/YKJ grid, the local ETRS-TM grid and the national ETRS-TM35FIN grid. Old maps primarily show the metric (KKJ/YKJ) coordinates. Finnish abbreviations related to declination: Nek and Nak give declination and difference between map north (by some definition) and true north respectively, add them (keeping the signs) to get the total correction to use (probably either in degrees or in mils as explained above).

The data is free (since spring 2012) and available in digital form, packaged commercially and by hobbyists (but maps included in or sold for navigators are sometimes of lesser quality). The data is used by OSM and thus by OSM based apps. The map sheets are also available for free download as png files (registration mandatory) at the National Land Survey; topographic raster maps 1:50,000 are about 10 MB for 50×25 km.

Online maps for all the country with Metsähallitus trails and services marked (most municipal and private ones missing) are available for general use and mobile devices.

Explanatory texts are usually in Finnish, Swedish and English. Maps can be ordered e.g. from Karttakeskus.

For Iceland there are sérkort in 1:100,000 scale with walking path information. Online map from the national land survey.

For Norway there are Turkart (including trail and hut information etcetera; 1:25,000, 1:50,000 and 1:100,000) and general topographic maps by Kartverket (1:50,000, 1:100,000 and 1:250,000). Maps at 1:50,000 give enough detail for navigation in difficult Norwegian terrain (standard maps in Norway), maps 1:100,000 tend to be too course for hiking. Maps at 1:250,000 can be used for general planning, but not for navigation in the wilderness. Maps can be ordered e.g. from Kartbutikken or Statens Kartverk (dead link: December 2020). Electronic maps are available from Norgesglasset. Online map for general planning is provided by the Trekking Association (DNT). The DNT maps also have information on huts and routes. Although the info is in Norwegian, it is in a standard format, quite easy to grasp. Note that walking times are given as hours of steady walk, you have to add time for breaks, and you might not be able to keep the nominal speed.

Lantmäteriet, the Swedish mapping, cadastral and land registration authority, used to publish printed maps of Sweden. Since 1 July 2018 they only publish maps on their website, where it is possible to download maps in the scales of 1:10 000 and 1:50 000.

For fell areas in Sweden there were two map series by Lantmäteriet, Fjällkartan 1:100 000 covering all the fell area, and Fjällkartan 1:50 000 covering the southern fells. The maps included information on trails, huts, weather etcetera, were adapted to the trails and overlapped as needed. They were renewed every three to five years.

For most of the country there is Terrängkartan (1:50 000, 75 cm x 80 cm). The road map, Vägkartan (1:100 000), covers the area not covered by Fjällkartan and includes topographic information. It may be an acceptable choice for some areas.

Lantmäteriet has an online map.

Maps are often for sale in well equipped book stores, outdoor equipment shops and park visitor centres. Maps for popular destinations may be available in all the country and even abroad, maps for less visited areas only in some shops. Ordering from the above mentioned web shops is possibly restricted to domestic addresses.

Note that maps, especially when based on older data, can have coordinate systems other than WGS84.

In border areas you often need separate maps for the countries. Some electronic maps handle the situation badly (the device showing blank areas of one map instead of information of the other map).

Polaris (North Star) is high in the sky, often seen also in sparse forest, but low enough that the direction is easily seen. Other natural orienteering aids include ant nests (built to get as much warmth from the sun as possible, thus pointing to the south), moss preferring the shadow and the boundary between grey and red of pine tree trunks, being lower on one side.

Fording

.jpg/440px-Wading_on_Iceland_(4).jpg)

On marked routes there are usually bridges or other arrangements at any river, but at least in the backcountry in the north, in the mountains and in Iceland there are often minor (or "minor") streams too wide to jump over. In times of high water fording may be difficult or even impossible. Asking about the conditions beforehand, being prepared and – if need be – using some time to search for the best place to ford is worthwhile. Asking people one meets about river crossings ahead is quite common.

In Norway and Sweden it is common to have "summer bridges", which are removed when huts close in autumn. Off season you have to ford or take another route unless there is strong enough ice or snow cover. It is not always obvious from the maps what bridges are permanent (and permanent bridges can get damaged by spring floods or exceptional amounts of snow). Not all bridges are marked at all on the maps, so you can have nice surprises also.

At some crossings there may be special arrangements, such as safety ropes. At lakes or gentle rivers there may be rowing boats, make sure you leave one at the shore from where you came.

Often the streams are shallow enough that you can get to the other side by stepping from stone to stone without getting wet (at some: if you have rubber boots or similar); in the Norwegian guides: steingåes. The stones may be slippery and may wiggle; do not take chances.

In a little deeper water you will have to take off boots and trousers. Easy drying light footwear, or at least socks, are recommended to protect your feet against potential sharp edges. If you have wading trousers, like some fishermen, you can use those to avoid getting wet. A substitute can be improvised from raingear trousers by tying the legs tightly to watertight boots (e.g. with duct tape). Usually you get by very well without – avoiding drenching boots and raingear would your construction fail.

When your knees get wet the current is usually strong enough that additional support, such as a walking staff or rope, is needed. Keep the staff upstream so that the current forces it towards the riverbed, make sure you have good balance and move only one foot or the staff at a time, before again securing your position. Do not hurry, even if the water is cold. Usually you should ford one at a time: you avoid waiting in cold water or making mistakes not to have the others wait. People on the shore may also be in a better position to help than persons in the line behind.

Unless the ford is easy, the most experienced one in the company should first go without backpack to find a good route. If you have a long enough rope he or she can then fasten it on the other side. A backpack helps you float should you loose your balance, but it floating on top of you, keeping you under water, is not what you want. Open its belt and make sure you can get rid of it if needed.

The established place to cross a river is often obvious. Sometimes an established ford is marked on the map (Finnish: kahlaamo, Swedish, Norwegian: vad, vadested), sometimes it can be deduced (path going down to the river on both sides), sometimes you have to make your own decisions. Always make a judgement call: also established fords can be dangerous in adverse conditions, especially when you lack experience. Never rely on being able to ford a river that can be dangerous, instead reserve enough time to avoid the need if fording looks too difficult.

When searching for where to cross the river, do not search for the narrowest point: that is where the current is strongest. A wider section with moderate current and moderate depth is better. Hard sand on the riverbed is good, although not too common. Sometimes you can jump over the river at a gorge or on the stones in a rapids, but do not gamble with your life (mind wiggling or slippery rocks, loose mosses etc.).

Timing can be key at some fords. With heavy rains you should probably ford as soon as possible or give up. Rivers with snow or glaciers upstream will be easier the morning after a cold night.

For some rivers you just have to go upstream until they are small enough. This happens when a bridge is missing or you are hiking at a time of high waters. If the river comes from a lake with several tributaries, finding a route above the lake is often a solution. You might also follow a route on ridges instead of in the river valleys, to avoid going up and down at individual streams.

At rare occasions the best way to cross a river may be to use an improvised raft, which can be constructed e.g. from your backpacks, a tarp, rope and a couple of young trees. Make sure your equipment is well packed in plastic bags and that there is no current getting you into danger.

In winter you can often cross rivers on the snow and ice, but this is a double edged sword: ice thickness in fast flowing rivers varies drastically and there can be open water, or water covered only with a snow bridge, also in extreme winters. Snow bridges crossed by an earlier company may collapse for you. Do not rely too much on your judgement if you lack experience.

By foot

For short hikes you might not need any special equipment.

In most areas wet terrain is to be expected. Maintained hiking trails do have duckboards at the worst places, but they are not always enough.

In some mountainous areas the terrain is rocky and sturdy footwear is necessary.

In remote fell areas there are few bridges and bridges marked on your map may be missing (destroyed by flooding rivers or removed for the winter). Be prepared to use fords and perhaps improvised rafts. Water levels may be very high in the spring (downstream from glaciers: the summer) or after long-time heavy rains, making wading dangerous also in streams that are otherwise minor. You can usually get information at least on marked trails and on the general situation in the area from park visitor centres and tourist businesses catering to hikers. On marked routes the river crossings should not be dangerous or require special skills during normal conditions, but always use your own judgement.

There are vast bogs in some areas. Before you go out on one, be sure you can get off it. The main problem is losing your way such that when you give up and turn back, you find too difficult spots also there. Avoiding these you will get more and more off your original route. Remembering the used route accurately enough is surprisingly difficult.

By ski

Winter hikes are usually done by cross country skis. The more experienced hikers have skis intended for use also outside tracks, which enables wilderness tours, in landscapes which look untouched by man. Also with normal cross-country skis you can experience astonishing views, along prepared tracks or near your base, in some conditions also on longer tours without tracks.

Where there are hiking trails, there are often marked cross country skiing routes in the winter, with maintained skiing tracks. The route often differs from the summer routes, e.g. to avoid too steep sections or take advantage of frozen lakes and bogs. The standards differ. Near cities and ski resorts the routes may have double tracks, a freestyle lane and lights, while some "skiing tracks" in the backcountry are maintained just by driving along them with a snowmobile once in a while. A few skiing routes are even unmaintained, meaning you have to make your own tracks even when following them, unless somebody already did. Mostly the tracks are groomed regularly, but not necessarily shortly after snowfall. On tours arranged by tourist businesses, you may sometimes have tracks made specifically for you.

When there are snowmobile tracks it may be easier to follow them than to ski in the loose snow. Beware though, as snowmobiles follow their routes with quite high speed and tracks made by independent drivers can lead you astray.