Sami culture

Sami culture

The Sámi are an indigenous ethnic group, endemic to the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. Their total population is just short of 100,000 people.

The Sámi National Day is celebrated on February 6. This date the first Sámi congress was held in 1917 in Trondheim.

Regions

- Norway: Trøndelag, Nordland, Troms and Finnmark

- Sweden: Norrbotten County, Västerbotten County and Jämtland County

- Finland: Finnish Lapland; <br>Enontekiö, Inari, Utsjoki and part of Sodankylä are recognised as the Sami native region

- Russia: Kola Peninsula

Cities

- Inari (Anár, Aanaar, Aanar) – the capital of the Sámi in Finland, seat of the Sámi Parliament of Finland

- Jokkmokk – a Sami town in Sweden with an annual fair in February

- Karasjok (Kárášjohka), Finnmark, Norway – a village where the Sámi Parliament of Norway is located

- Kautokeino (Guovdageaidnu) – a centre of Sámi culture having over 90% Sámi population

- Kiruna (Giron) – the seat of the Swedish Sami Parliament

- Lovozero (Luujäuˊrr) – Centre of the Kildin Sami in Russia

- Sevettijärvi – centre of the Skolt Sámi in Finland

- Östersund (Staare) – town with the Sámi information centre of the Swedish Sámi parliament

Other destinations

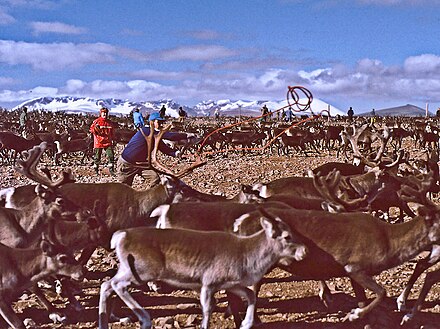

Sámi culture is not about city life. Although you will meet authentic Sámi in the towns, find museums, shops and exhibitions there and may have the chance to participate in Sámi festivals, an understanding of the Sámi necessarily includes a feeling for the vast areas outside cities. If you have time and are lucky you may join Sámi working with the reindeer on the fells. If you are a hiker you will appreciate the large wilderness areas. Otherwise you may get on an arranged tour, perhaps fishing in a lake far from the busy modern life.

Understand

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Sametingsr%C3%A5det_(10324573015)_(cropped).jpg)

The Sámi call their homeland ("the Sámi land") Sápmi (Northern Sámi), Sámeednam (Lule Sámi), Saemie (South Sámi), Säämi (Inari Sámi), Sääʹmjânnam (Skolt Sámi) or Sábmie (Ume Sámi). This land does not have a clear boundary but includes the northern part of the Scandinavian peninsula, northern Finland and the Kola peninsula. The border between Norway and Finland is more than 700 km long and runs through the Sami heartland, as does the northern section of the border between Norway and Sweden. Sápmi is largely north of the arctic circle, with a mostly subarctic climate with cold (or very cold) winters. Coastal areas have milder winters. The land is generally sparsely populated with about 2 inhabitants per square kilometre.

Sami languages are Uralic languages related to Finnish and Estonian, but unrelated to Indo-European languages, such as Norwegian, Swedish, English or Russian. Sámi is not one language (although treated as one in much legislation), but a family of languages, neighbouring ones usually mutually intelligible. Sámi is an official language in Norway and within some districts equal with Norwegian, a recognised minority language in Sweden, and a co-official language in northernmost Finland. It is the only language mentioned specifically in Norway's constitution. Some Sámi languages have been written since the 1600s, although the current orthography is from the late 20th century.

During the Middle Ages the Sápmi was known as Finnmǫrk in old west Norse (old Norwegian), this was not an area with clear borders and the area changed over time. A 12th century Latin description of Norway identified the coastland and the hinterland, in the latter the Sámi "live but don't plough" (that is, the Sámi were not farmers). From the Viking age to the Reformation, Norse settlements expanded along the coast north of Lofoten. Until about year 1400 Malangen fjord was regarded as the border between Norse-dominated area and Sami areas, even if there were non-Sami fishing posts further north and east as well as a church and fortress in Vadsø. South of Narvik the border between Norway and Sweden was largely fixed since the Middle Ages, but in the core Sami (and reindeer husbandry) areas further north there was no clear border. Sami people moved freely with their reindeer between Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, and wide areas in the interior were regarded as "joint districts". The border treaty of 1751 fixed the border between Norway and Sweden/Finland once and for all. The border cut right through Sápmi and special addition to the treaty defined the rights and duties of the Sami.

The Roman historian Tacitus in the first century wrote about Fenni that may also have included both Sámi and Finnish people. In the 6th century historians wrote about scritiphini that originates from Old Norse skríðfinn meaning "skiing finns" (finn meant Sámi at that time): For Norse people living along the coast and further south the Sámi people was associated with skiing. Noted explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen assumed that Sámi introduced skiing in Norway. Rock carvings in Nordland, in Alta and in northern Russia show prehistoric hunters on skis.

About 30,000 people speak a Sámi language. As ethnic backgrounds are not recorded (except in Russia) and definitions vary, the exact number of Sámi are not known. Estimates range from 50,000 to 100,000 persons. The Sami parliaments in Finland, Norway and Sweden (Northern Sami: Sámediggi, Finnish: Saamelaiskäräjät, Norwegian and Swedish: Sametinget) have authority and budget primarily in cultural areas and act mainly in a consultative role in other areas.

Reindeer husbandry has been – and still is – an important livelihood among the Sámi and the culture surrounding the trade is important also for many with other professions. Even traditionally, though, not all Sámi have been involved in reindeer husbandry, but lived from fishing, hunting and similar, having reindeer mostly as draft animals. Today most Sámi work in modern trades and only a small minority actually work in the reindeer business. Tourism is an increasingly important income in the area.

As reindeer herders or hunters, the Sámi traditionally followed the animals on their seasonal migrations, having a winter village, calving and autumn grounds, summer grounds, and mobile homes (_goahti_s and _lávvu_s). As the movements between pastures took quite some time, they had eight seasons, not four. Also those living mainly from fishing moved as seasons changed. The reindeer still have seasonal pastures (mostly treeless areas in summer, either in high terrain or by the coast) but the borders between the countries closed in the 19th century, restricting the migration. With the introduction of motorized terrain vehicles (most importantly the snowmobile), reindeer herders have been able to reach their livestock from a permanent home. Some of the people you might meet were born before this revolution, and some choose to still live in or near the traditional summer settlements in summer, close to the livestock.

During the 18th century the Sámi became a trendy and exotic subject to Central European adventurers and scholars. Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus travelled Arctic Scandinavia in 1732, and described the Sámi lifestyle. The linguistic relationship between Sámi language(s) and Hungarian was revealed already in 1771. Yet most of the area was connected to the road and electricity grid only after World War II.

Today many tourists in Sápmi want to experience the exotic Sámi culture. This has led to non-Sámi dressing in quasi-Sámi clothes and performing "Sámi" rituals (thought of as insults by many Sámi). You may enjoy these shows for what they are, but if you want to learn about Sámi culture, you should be wary of the difference. On the other hand, real Sámi are, despite preserving a distinct culture and identity, to varying degrees integrated in the modern lifestyle, and marriages across the cultural borders are quite common – you should not try too hard to find "authentic" Sámi.

Sámi people usually don't stand out among other inhabitants. Somebody wearing a full traditional dress (outside festive occasions) or a Sámi hat is most likely a non-Sámi tourism entrepreneur. The sharp-eyed may sometimes see hints on Sámi background, such as details in the clothing or a name common among the Sámi, but the best advice is probably to show appropriate interest, like you would with a presumably native New Yorker in New York, and a local just might get talkative. If you are going to pay for programme services you can of course ask about their relation to traditional Sámi lifestyle (nothing wrong in going on a husky ride, but they were introduced in Sápmi only in the 1980s, mostly by southerners).

The joik is a Sámi singing style, which still is a living, continuous tradition, but also is re-interpreted today as a genre of popular music; see Nordic music.

Talk

.jpg/440px-Billeder_fra_Lappernes_Land-Tableaux_du_Pays_des_Lapons_-_Norsk_folkemuseum_-_NF.15006-195_(cropped).jpg)

There are nine existent Sámi languages, although Northern Sámi is by far the most widely spoken and understood also by many Sámi not having it as mother tongue. Unfortunately, because of earlier language policy, not all Sámi speak Sámi at all. All speak the majority language of the country and they study English in school like other citizens of their respective countries. In Finland, Swedish is non-compulsory for those getting their education in Sámi (and thus reading Finnish as another domestic language).

Most places in Sápmi have Sámi names. The names in the non-Sámi languages are often based on these, although the spelling may be quite different. Sami place names often describe the place in some sense, so knowing some basic words for different types of terrain may actually appear useful while trekking!

One can study Sámi languages as a major at least in the University of Oulu. The Sámi University of Applied Sciences, University of Helsinki, Sámi Educational Centre (dead link: January 2023), University of Umeå, and Sami Education Institute (SOGSAKK) offer language courses for different Sami languages.

There are programmes in Sámi on the public service networks: check e.g. Ođđasat for news in Sámi, or Unna Junná for some children's programmes.

Get in

There are quite a few airports in the Sápmi area, with at least domestic flights. Kittilä in Finland has relatively many seasonal flights from European destinations.

The railways in Finland terminate at Kolari and Kemijärvi, with Rovaniemi the most important hub for continuing by coach.

Swedish trains go to Kiruna, and to Narvik in Norway. Inlandsbanan is usable too.

The Norwegian trains terminate at Bodø.

Russian trains go to Murmansk, and with sparse services somewhat beyond.

For Norway, the Hurtigruten ferry service is an option.

European routes such as E6, E45 and E75 reach Sápmi and can be used by those arriving by car or coach.

Get around

The area is served by coaches, mostly at least with daily services. If you use your own car, be wary of the Norwegian terrain (there is quite a difference between the shortest route and the route by car) and driving conditions in winter. The distances are long, so biking requires some dedication. Taxis are a viable option for some destinations.

See

-Riksantikvarie%C3%A4mbetet.jpg/440px-16000300032226-Vastenj%C3%A1vrre_(Vastenjaure)-Riksantikvarie%C3%A4mbetet.jpg)

Museums

- Most national park visitor centres in Sápmi tell also about the Sámi and their culture.

In Finland

- Siida (Inari Sámi Museum), Inarintie 46 (Inari, Finland), 68.91021°, 27.01295°, +358 400-898-212, siida@samimuseum.fi. 1 Jun–19 Sep: 09:00–20:00; 20 Sep–31 Mar: 10:00–17:00. The National Museum of the Sámi in Finland. Both indoors and open air exhibitions. Large museum shop with souvenirs, handicrafts and literature on local Sámi languages. Adults: €10, Finnish Museum Card valid.

- Skolt Sámi Heritage House (Nuõrttsaa´mi Ä´rbbvuõttpõrtt), Sevettijärventie 9041 (Sevettijärvi, Finland), 69.5093°, 28.5942°, +358 400-373-015. July–August 10:00–16:00. Small museum about the Skolt Sámi and their life. Small museum shop with handicrafts and Eastern Orthodox religious items. The house is open in July–August. Their open air exhibition is open around the year but the area is not maintained in winter. Free 2020-07-30

In Norway

- Alta Rock Carvings, 69.976667°, 23.295833°. A UNESCO World Heritage Site. Rock art is found in five separate areas in Alta, the largest and the only area available to the public being at Hjemmeluft/Jiepmaluokta, where Alta Museum is situated. In the summer season, groups are offered guided tours to the rock carvings. In the winter, the rock carvings are covered with snow, and not available to the public. The rock carvings in Alta were made by hunters and fishers in the Late Stone Age/Early Metal Age, between 6200 and 2000 years ago.

- Sámi Museum in Karasjok, Mari Boine geaidnu 17 (Karasjok, Norway), 69.4733°, 25.5200°, +47 78-46-99-50, post@rdm.no. in summer daily 09:00–18:00. The largest museum about Sámi cultural history in Norway. Both an indoor exhibition and an open air museum. adults 90 kr, students 60 kr, children under 15 free 2020-07-30

- Varanger Sámi Museum (Várjjat Sámi Musea), Endresens vei 4 (Varangerbotn, Norway), 70.1725°, 28.5579°, +47 95-26-21-55, vsm-info@dvmv.no. June–August daily 09:30–16:30; otherwise M–F 10:00–17:00. Rather large museum mostly on the Coastal Sámi culture. Museum shop. adults 80 kr, students 40 kr, children 30 kr 2020-07-30

- Mortensnes Cultural Heritage (Geavccageađge), Mortensnes (Nesseby, Norway), 70.1278°, 29.039°, +47 41-07-00-50. in summer daily 10:00–16:00. Open air museum at a site where Coastal Sámis or their predecessors have lived for 10,000 years. Digital guide available. The Geavccageađge holy stone pillar and a burial site used for about 2,000 years until the 1600s. Awesome views. Café and changing exhibition indoors. Free 2020-07-30

- Ä´vv Skolt Sámi museum (Ä´vv Saa´mi Mu´zei), 69.6995°, 29.3778°, +47 95-26-21-63, chma@dvmv.no. mid-June to mid-August daily 10:00-17:00; otherwise M-F 10:00-15:00. Large museum about the Skolt Sámi, opened in 2017. The main exhibition tells about Saaʹmijânnam, the (Skolt) Sámi Land. Changing art exhibitions. A few kilometres south there is also an open air museum consisting of Eastern Orthodox St. George's Chapel from 1565, and a traditional Skolt summer village. adults 80 NOK, students and children under 16 yo free 2020-07-30

- Kautokeino municipal museum (Guovdageainnu gilišillju), Boaronjárga 23 (Kautokeino, Norway), 69.0084°, 23.0476°, +47 481 17 266, rdm-kauto@rdm.no. Museum opened in 1987. Both indoors and open air exhibition. The Church hut, built in 1650, is the oldest standing building in Finnmark. adults 50 kr, children under 15 free 2021-02-05

- Kokelv Coastal Sámi Museum (Jáhkovuona mearrasámi musea), Kokelvveien 25 (Jáhkovuotna – Kokelv, Norway), 70.6111°, 24.6343°, +47 47-32-68-62, kjersti@rdm.no. Tu–Su 11:00–17:00 (mid-June to mid-August only), M closed. A tiny museum about Coastal Sámi culture in a post-WW2 built Coastal Sámi household. Boat collection. 50 kr, children under 15 free 2020-12-17

- Saemien Sijte, Ella Holm Bulls veg 30 (Snåsa, Norway), 64.2474°, 12.3587°, +47 74-13-80-00, post@saemiensijte.no. mid-June to mid-August M–F 10:00–17:00, Sa–Su 11:00–17:00. Culture centre and museum on Southern Sámi culture, including its roots. Also changing art exhibitions. Hosts many Sámi cultural events. 50 kr 2017-12-15

In Sweden

- Ájtte, Kyrkogatan 3 (Jokkmokk, Sweden), 66.6038°, 19.8411°, info@ajtte.com. The national museum of Sámi culture in Sweden. Exhibition about the Fell Sami culture and the nature at the fells. adults 90 kr, children under 16 free 2020-07-30

- Nutti Sámi Siida – Reindeer park and Sámi camp, Marknadsvägen 84 (Jukkasjärvi, Sweden), 67.8539°, 20.5807°, +46 980 21329, info@nutti.se. Winter season: 1 Dec–14 Apr daily 10:00–17:00; summer season: 17 June–11 Aug daily 10:00–16:00. Reindeer and information about the Sámi people. Café and handicraft shop. Winter: adult 150 kr, student 100 kr, children 75 kr. Summer: adult 180 kr, student 120 kr, children 80 kr

Theatres

- Beaivváš Sámi Našunálateáhter in Kautokeino, Norway

- Giron Sámi Teáhter in Kiruna, Sweden

Itineraries

- Padjelantaleden through the national park Badjelánnda (Swedish: Padjelanta), part of Laponia: in Badjelánnda, the local Sámi communities run the wilderness huts and a few are at Sámi settlements, where you can buy fresh fish and bread of the local Sámi.

Do

- St Mary's Day Celebrations (Márjjábeaivvit). Late March. Dance, music, lassoing competitions, reindeer races. Handicrafts for sale. 2017-07-15

- Easter festival (Beássašmárkanat). Easter, programme all week. Festival with exhibitions, races, ice fishing, film and music festivals, concerts. The Easter has been an important time, the last chance to gather with friends before it is time to move the reindeer to the calving grounds. 2017-07-15

- Jokkmokk Market (Jåhkåmåhke márnána). First Th–Sa in February. Held since 1605. Local handicraft, Sámi produce and ordinary market fare; also a big cultural happening.

Music festivals

- Riddu Riđđu, 69.5274°, 20.5309°. Indigenous music festival in Olmmáivággi (Norwegian: Manndalen) village in Kåfjord municipality and held every July since 2007. Most artists are indigenous musicians from outside the Sami area. The festival's name is Northern Sami for Coastal Wind. 2020-07-30

- Ijahis Idja, 68.9068°, 27.0123°. Indigenous music festival held in Inari village in August since 2004. The event is concentrated on traditional and modern Sami music. The name is Northern Sami for Nightless Night. 2020-07-30

Film festivals

- Skábmagovat, 68.9068°, 27.0123°. A film festival in Inari is concentrated on indigenous cultures, especially the Sami. Arranged every year late-January. The name of the event means 'polar night pictures' in Northern Sami. 2021-01-18

Buy

Sámi handicraft makes good souvenirs, but check that it is authentic. In shops the item should have the Sámi duodji (literally: Sámi handicraft) mark. Typical materials are wood, leather, wool, horns and bones. Silver has been highly appreciated material in traditional Sámi jewelry.

In addition to traditional handicraft, there are quite a few artists making modern jewelry with strong roots in the Sámi culture. Their products may however not be on sale locally, other than possibly from their workshop at home.

Be especially wary about clothing. Sámi hats and dresses are virtually always fake, as a Sámi dress, gákti, is made for a specific person, with lots of symbolism about the home village, family and person of its user. Those who do the fakes often do not even know what details belong to a man's dress or woman's dress. However, a traditional scarf, liidni, is a prestige, commonly available, and (if authentic) quite expensive souvenir.

Eat

See also: Nordic cuisine

As agriculture is quite a hopeless try with most crops at these latitudes, most dishes are based on reindeer, fish and game. Also some wild plants play or have traditionally played an important role, such as berries, especially cloudberry and crowberry. The Norwegian angelica (Northern Sámi: Olbmoborranrássi, Norwegian: kvann, Finnish: väinönputki) has been important vegetable and also medicinal herb. The Sámi still have their own bread types, such as flatbread called gáhkku which is traditionally baked on a stone by open fire.

Drink

Sleep

As the Sámi lived semi-nomadic lives wandering between summer and winter locations they had mobile homes. The lávvu is made from straight tree stems (resembling a teepee) and thus easy to build from scratch in fell birch forest (if you have the fabric or hides to cover the structure), while the goahti is more elaborate, with larger sitting-height floor area. The lávvu stems are often left behind for next use, while the goahti trees are carried along. There are also permanent goahtis made from timber or peat. Especially the Skolt Samis gathered into winter villages for the winter. In such villages each family had their permanent house. These mobile and stationary homes are still commonly used, both as tourist attractions and as traditional accommodation, although not as primary home any more.

Many tourist businesses invite you to drink coffee by the fire in a lávvu. Nearly always you will get more familiar lodging for the night, in a few cases with something built to resemble a lávvu, but with normal beds and mattresses.

Stay safe

Sápmi, the Sámi region, is mostly very sparsely populated, with a harsh or even extreme climate. Do not venture into the wilderness without proper skill and equipment.

Follow instructions and take care when driving snowmobiles. Sámi drivers are usually very experienced, so watching them may make driving in the terrain seem easy. Off well-maintained routes it is not. Turning over or hitting a tree can be fatal. Also mind ice safety-

Respect

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Kongen_ankommer_(11084701965)_(cropped).jpg)

Sámi are often known in other languages as Lap, Lapons, Laplanders or similar, but many of them regard these as pejorative and obsolete terms. Use the word Sami for the ethnicity and the language, and Sápmi for their collective territory. Lapland is still used as names for the northernmost provinces of Finland and Sweden, and in a wider sense in some touristic or misguided publications, for areas never locally called so. Norway's northernmost county is Finnmark, "land of the Finns", as Sami people were previously often referred to as Finns (but Sápmi includes most of Northern Norway).

Especially during the 20th century the Sámi have been subject to severe assimilation and racial policy and therefore many ethnic Sámi have never learned to speak their language and may even feel their ancestry shameful.

The Sámi community has some unresolved disputes internally, as well as with the national governments, and the majority population. Land management rights (including mining, forestry, reindeer herding, fishing, and wildlife management) is a particularly sensitive topic.

Go next

- Nenetsia with the Nenets people, an other reindeer herding people of the Arctic. Advance research is needed though, as most Nenets villages are very remote and English proficiency scarce.

See also

- Ice Age traces for North European geology

- Vikings and the Old Norse for early Scandinavian history

- Minority cultures of Russia

- Norrbotten Megasystem

Related Wikipedia article: Sami people