Vikings redirects here. For the town in Alberta, see Viking (Alberta) The Nordic countries are remembered for the Viking Age, a period during the 9th and 10th centuries, when the Norsemen sailed the seas and rivers of Europe, reaching as far as Canada, North Africa, and Central Asia. Before the Viking Age, Northern Europe also has an interesting prehistory, going back to the end of the Ice Age, around 10,000 BC.

Understand

See also: European history

Many English-speakers who visit Scandinavia ask where they can see real Vikings. However, no tribe or nation has ever been called Viking; it is simply the word for "sailor" or "pirate" in Old Norse, the language spoken in Denmark, Norway and Sweden before AD 1000. The exact origin of the word viking is still disputed. In the Norse language, viking referred to a person as well as an activity or concept; "to go viking" or "to be away on viking". While some Norsemen travelled overseas for settlement, fishing and commerce, and a few pursued a career as bandits or mercenaries (the true Vikings), most remained in Scandinavia, living from farming and other mundane professions.

Iceland and the Faroe Islands were settled by Norsemen in the 9th century, and there were also Norse settlements in Great Britain and associated islands. Dublin was founded as a Norse or Viking settlement before year 1000. In Finland, and the northernmost parts of Sweden and Norway, the Finns and the Sami people reigned since prehistory. The Finns and the Sami are both Finno-Ugric people, and their culture and way of life was completely different from the Norse until their homelands were annexed by Sweden and Norway during the 13th and 14th centuries.

Old Norse prehistory

See also: Ice Age traces

See also: Ice Age traces

During the last Ice Age, almost all of Scandinavia was covered with glaciers most of the time, but around 10,000 BC, as the temperatures increased, a general retreat of the solid ice cover began. The Norse creation myth, in line with reality, describes the Norsemen's homeland as created from ice melting from a burning fire. According to the myth, the melted ice revealed the giant Ymir, later slain by the gods, who built the Earth out of his body. Relieved from the heavy ice cover, the Scandinavian peninsula has been steadily rising since the end of the Ice Age, at some places as much as 1 meter every 100 years. Therefore, the scenery and coastlines have been changing, and many fairways of the Vikings are dry land today.

Remains from Stone Age hunters temporarily visiting Scandinavia during short warm epochs in the last Ice Age have been uncovered, but the cave in Karijoki is the only known pre-glacial human settlement in all of Scandinavia.

The first settlers followed the melting ice. Farming and metalworking spread from southern Europe to Scandinavia; however, there are plenty of archaeological sites, with remnants of pottery and rock carvings. While metalworking and other crafts were imported from further south, the three-age system (stone, bronze and iron age) is actually based on Nordic archaeology.

The inhabitants of Scandinavia comprised many different tribes such as the Swedes, Geats, Gutes (perhaps related to the Goths), Augandzi, Ranii, Halogi, Herules, Jutes and later the Danes, but all shared a somewhat similar Norse culture – except the nomadic and shamanistic Sami – heralding the Norse Gods, speaking the Old Norse language and using a common runic alphabet. The Norse were Germanic people who were culturally linked to the many other Germanic tribes in the rest of Europe, but when mainland Europe and the British Isles were Christianized during the first millennium AD, the Germanic pagan culture and mythology continued to prevail in Scandinavia.

The Norse never isolated themselves from the world. They maintained important trade links with both the European Celtic and Slavic tribes and the Roman Empire, exchanging prized goods like wool, furs, walrus ivory and amber (see Amber Road) for wine, glass and precious metals and they had long been sought after as mercenaries and guards for the Romans.

During the Migration Period from the 4th to 8th centuries, some tribes migrated south from Northern Europe, towards the Mediterranean. Due to lack of reliable sources, the line between fact and fiction is hard to draw. The Goths, who invaded Rome during the 5th century, are believed to have partially descended from southern Scandinavians from either Götaland or Gotland. The Vandals, who settled in North Africa, are also said to have Scandinavian roots. While archaeological evidence is too scarce to either confirm or refute these theories, they have survived as legends of a Scandinavian "golden age".

The "Vendel period"

The early 6th century was a very disruptive period in Nordic history. Due to a combination of factors, including the final days of the migration era, the Justinian plague, and some global extreme weather events in 535–536 which caused a minor ice age, a lot of old Nordic settlements were abandoned while new ones were established. During this era many traits which became characteristic for the Viking era, such as the clink-built boats and the popular animal ornamentation art style, were developed. The new culture which evolved in the 6th century is called the "Vendel-era" in Swedish historiography after a rich 7th-century boat burial field in Northern Uppsala County. In the Anglo-Saxon world it might be best known as the era of Beowulf, an Old English epic poem set in 6th-century Denmark.

This period saw the establishment of the thing, an assembly where the free men of a country or a province could settle disputes; at times with the authority to elect or remove a king. The word has survived to modern legislature, such as the Norwegian Storting, the Danish Folketing, and the Icelandic Alþingi; the world's oldest extant parliament, founded in 930 AD.

Uppsala was the political and religious centre of the land that would eventually become Sweden, with a renowned pagan temple and "the Thing of All Swedes". The Swedish kings were buried next to the temple in monumental burial mounds which still exist. The era is also known for its many boat graves, such as those in Vendel and in Valsgärde near Uppsala. They are similar to the famous contemporary boat grave in Sutton Hoo in Eastern England, indicating that the Vendel-era Norsemen still had some contacts with their Anglo-Saxon cousins. Many of these Vendel-era graves are even richer and more lavish than those of the later Vikings.

In the 8th century the Vendel-era developed into the Viking-era, as the Norsemen took a much more active stance on the international stage.

The Viking Age

The Viking Age has no clear limits in time. Norsemen have travelled overseas since time immemorial, but journeys became longer and more frequent during the 8th century, with the raid at Lindisfarne in AD 793 usually held as the beginning of the era. The Christianization and unification of the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in the 11th century marks the end of the Viking Age.

Most Swedish, Norwegian and Danish people relied on local farming, fishing, hunting and some crafts and commerce in the Nordic Iron Age, but with the onset of the Viking Age, and for reasons that are still unclear, large, well-organised expeditions to destinations outside Scandinavia commenced, settling as far as Greenland and Canada and raiding as far as The Black Sea and Morocco and the Islamic Caliphate. Some of the Norse expeditions in the Viking Age revolved around commerce and exploration; others were more or less pure raids, making the Norse known and feared as Vikings throughout Europe. Norse people also took employment as bodyguards and mercenaries, and settled in areas such as the British Isles (see Medieval Britain and Ireland) and Normandy. The Norse came to play important roles in the foundation of great nations such as the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of France and England. Over the centuries, the violent raids were commuted to extortion of tribute, and formal taxation. The Danegeld was a tribute paid by local English lords, with similar schemes among Franks, Slavic and Sami people to buy off Norse raiders. Over time, the taxation came to fund the lords' fortifications and defense forces to fight off the Norsemen.

While Viking raiding pirates, who sacked monasteries and other settlements, were only one aspect of Norse culture, this was what they became known and feared for around Europe at the time, especially in France and the British Isles. Most records about Vikings in their own age were written by their enemies or Christian missionaries, with a bias to describe them as more brutal than they actually were, leading to the stereotype of the Norse as nothing more than savage, bloodthirsty, barbaric heathens. The Norse of the Viking Age are still generally (incorrectly) referred to as Vikings today. Our knowledge of the silent majority of sedentary Norse farmers is limited to other sources.

Berserkers were Viking warriors who fought in a trance-like frenzy. According to the sagas, they worshipped the bear to achieve their strength (the word literally means "bear shirt"). Later theories explain the berserkers' fury by ingestion of alcohol or poisonous mushrooms, or mental conditions such as epilepsy or post-traumatic stress.

A shieldmaiden (skjaldmær) was a female warrior, curiously described by sagas and European chronicles. Today's scholars disagree how common they were; many Norse women's graves had war-themed gifts such as weapons, shields and strategic boardgames, to the extent that early archaeologists mistook female skeletons for males.

Thralls were slaves or serfs in old Norse societies; by birth, due to poverty, or prisoners of war. Wealthy landowners usually had thralls, and Viking expeditions usually aimed to capture or sell thralls. The English word slave is allegedly derived from the ethnic word Slav through Byzantine Greek, as some captive workers were from the Slavic peoples; usually from today's Ukraine. Slavery survived locally until the 13th century. A free man's title was karl, which is still the Nordic word for "man"/"fellow", and a common given name (Carl or Charles in English).

The Norse were the first people known to have crossed the Atlantic. Iceland was settled during the 9th century, with Reykjavík as its first settlement. Iceland was primarily settled by people from West Norway from around year 870 in the period known as the landgrab time. This period is described in a unique document, the Landnámabók (book of settlement or book of landgrab), where some 400 individuals are named.

There were Norse settlements also on Greenland and Newfoundland. Around AD 1000, an expedition led by Leif Eriksson left Greenland, crossed the Labrador Sea, and arrived at the Baffin Island and later Newfoundland, nearly 500 years before the voyages of Christopher Columbus. These settlements went extinct due to worsening climate, infighting within the communities, and conflict with natives.

The Normans

The Normans were descendants of Vikings who settled in northern France in the 10th century, giving their name to Normandy. They became faithful Catholics, and adopted a language similar to French. The Normans invaded England in 1066 and subsequently Scotland, Wales and Ireland, leading to an establishment of French culture on the British Isles until modern times.

The Normans integrated with the Kingdom of France, and up to the 15th century, Norman fleets waged wars all around Europe, as far away as the Canary Islands and Lebanon. They conquered Sicily and southern Italy and were again assimilated into the local culture.

Eastward exploration and the Rus

Vikings from Sweden settled in today's Baltic states, Belarus and Ukraine, travelling the rivers of eastern Europe with ease. They were the probable ancestors of the Rus people, the founders of the kingdoms that became Russia. The word rus can be traced to Roslagen (Sweden's coast to the Baltic Sea) and Ruotsi (the Finnish name for Sweden) and probably means "rower". Competing theories claim that the Rus came from the Caucasus.

There is some evidence that the Norsemen founded the Slavic nobility clans. They were in the end assimilated by the majority population, but vestiges of Norse culture lingered in eastern Europe as long as the 14th and early 15th centuries.

The Norsemen in eastern Europe made their living in various professions: as merchants, slave raiders or mercenaries, and formed the base of the Varangian Guard (væringr) of the Byzantine Empire.

The 12th and 13th centuries saw the Northern Crusades, in which Swedish and German knights tried to bring Christianity to Finland, the Baltic lands and Russia.

Norse ships and navigation

The Norse would never had made the impression they did without their outstanding ships. The warships were fast with little draught, allowing the ships to land on any beach and giving the locals little time to react on the approaching raiders. The light construction allowed ships to be portaged between rivers flowing to the Baltic Sea and those flowing to the Black Sea, and past the Dnieper Rapids. And there were ships seaworthy enough to allow crossing the Atlantic.

.jpg/440px-Saga_Siglar_(1983).jpg)

Replicas were built early on (one crossed the Atlantic for the world exhibition in Chicago 1893), but the research about the Norse ships has advanced enormously since the last turn of century. The Gokstad and Oseberg ships were quite complete, but they had partly collapsed, and reconstructing their form was an enormous jigsaw puzzle – and some short cuts were made. Computer models and simulations have given much more insight. The warships indeed had a planing or semiplaning hull, with longships believed to be capable of sailing up to 15–20 knots in ideal circumstances (nearly as fast as the much bigger clippers and windjammers of the last few centuries).

The longship replica Sea Stallion, built and operated as an experimental archaeology project by the Viking ship museum in Roskilde, sailed to Dublin and back 2007–2008. Much was learnt by trial and error, and the seaworthiness of the ship was confirmed. Although longships would prefer to (and the Stallion did) wait for good weather, it got gale force winds in adverse conditions in the North Channel and on the Celtic Sea. The voyage also confirmed that quite some skill and toughness was needed to successfully use this kind of ship.

Although the longships are the most famous ones – and versatile – the Norse had many types of vessel: smaller ones for coastal navigation and fishing, the higher and wider knarr and probably light ships for the rivers. The Viking ships were capable of beating, at least with the right sails (woollen sails tend to stretch out), but rowing or waiting for better winds was often preferred.

It must have been very tough to portage a ship capable of crossing seas and carrying significant numbers of men and cargo. Several journeys on the Russian rivers have been made with replicas, with varying levels of difficulty. As no ship known to have been used on these routes has been found, the projects had to choose a model (and adjust it) based on their own reasoning.

The knarr was seaworthy, sometimes decked, and mostly sailed (while the longships were often operated by oars on shorter passages). It was built for overseas trade, and the type used on most of the transatlantic voyages. One replica of a knarr, Saga Siglar, circumnavigated the globe 1984–1986, including a visit to Greenland.

It is not quite understood how the Norse were able to navigate the open sea. They had a good understanding of currents and winds, they used sightings of whales and birds, and they had some tools, such as sundials that seem to have allowed them to follow a latitude, and some sailors seem to have had "sunstones", which told the direction to the sun also when the sky was overcast (perhaps using polarization of the light).

Helmets

As in many other pre-modern societies, the Norse used animal horns as bugles, drinking horns, tools, trophies and possibly on ceremonial headwear, however not on combat helmets. The 1876 première of Ring of the Nibelung featured costumes with horned helmets, which might have popularized the trope. Today, horned helmets are a stereotypical Viking prop at sport events and costume parties.

As in many other pre-modern societies, the Norse used animal horns as bugles, drinking horns, tools, trophies and possibly on ceremonial headwear, however not on combat helmets. The 1876 première of Ring of the Nibelung featured costumes with horned helmets, which might have popularized the trope. Today, horned helmets are a stereotypical Viking prop at sport events and costume parties.

If you think about it, a horned helmet would be an immense disadvantage in a combat situation as your opponent could grab the horns, or a weapon that would otherwise be deflected could get caught in the horns, causing significantly more damage.

While the Norse blacksmiths were skilled, metal was a luxury. It is not clear whether Vikings used metal helmets regularly, or if they merely used a kind of leather hats for protection. In Norway, a single Viking-age metal helmet has been uncovered.

End of the Viking Age

The Norse people are generally understood to have been among the last Europeans to be Christianised. The first Christian missionaries arrived in the 9th century, but the church got a foothold only in the 11th century, as the Nordic kings were baptized. In Norway, the Moster assembly of 1024 accepted Christianity as the "law of the land". Bishop Ascer of Lund became Archbishop of Scandinavia in 1104, establishing Catholicism. Paganism remained in some areas until the 12th–14th century, with many cultural remnants even today.

In the 11th century, Sweden, Norway and Denmark became consolidated kingdoms; as well as England, Kievan Rus, and other nearby lands, with castles, town walls and standing armies making raids more difficult; though they went on well into the 12th century, with some of the most notorious Viking leaders being Christian monarchs, such as Saint Olaf II of Norway.

If a single ending year was to be selected, it would be 1066, when an English army defeated Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, and drove out the Vikings from England. On the same year, a Norman army invaded England in Hastings. The Hanseatic League came to dominate commerce on the North and Baltic Sea.

See Nordic history for the Nordic countries past AD 1000.

Old Norse heritage

With Christianity and monarchy around AD 1000 came stone churches, castles, and the first comprehensive written chronicles. By convention, this marks the beginning of historical time and the Middle Ages in Scandinavia, whereas in Western Europe, the 5th to 10th centuries are usually described as the Early Middle Ages, with the High Middle Ages following.

Most of what we think we know about pre-Christian Nordic people and their world comes from short runic inscriptions, 12th–13th century recordings of the famous Viking sagas, the Eddas and scaldic poetry that previously was taught by word-of-mouth. They also left behind an archaeological legacy of buildings, castles, crafts, burial mounds and ships that has been increasingly studied.

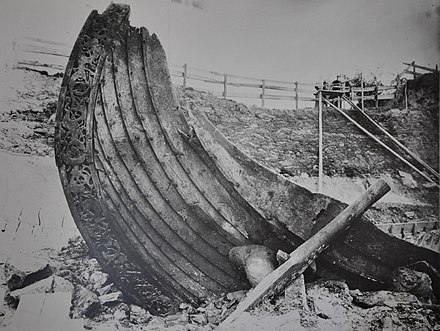

Viking ships, some largely intact, with other artifacts, have been uncovered from burial mounds. Stave churches emerged at the end of the Viking era and presumably reflect the wood technology and decorative art of Viking ships and houses. Around 30 such buildings (the oldest ones from the 12th century) survived in rural Norway, and can be seen on site.

Only fragments of Viking-age buildings have stood the test of time; today's "Viking" villages are modern replicas, though most of them have a high degree of realism.

Runes

The runic alphabet has been used by Germanic people at least since the 4th century AD. With Christianity came Latin script; runes remained for centuries and were used by Christians including clerics, but came over time to survive only in the countryside, associated with pagan rituals and magic. Some villages in Dalarna used runes into the early 20th century.

Most runic inscriptions are laconic, and can be found on a few preserved weapons, everyday utensils, and wooden sticks used in the same manner as notebooks or postcards. Runestones are on raised stones, boulders or outcrops, are the most persistent pieces of runes. Most of the 6,000 known runestones are in Sweden (with high concentration in Stockholm County, Uppsala County and Östergötland), Norway and Denmark. A few hundred runestones are known overseas; in Britain, Ireland, Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland. Some stones have been moved to museums.

Runestones took effort to make. Most were sponsored by a wealthy landholder, to venerate a dead kinsman. A typical example is the runestone U53 in Gamla stan in the middle of Stockholm, which says "Torsten and Frögunn had the stone raised for their son". While most runestones are presumed to be raised by sedentary families, a few of them describe voyages overseas (therefore usually the most famous and historically important ones).

Some runestones include pictures and ornaments. Picture stones (bildstenar) with narrative paintings are spread across northern Europe, and are common on Gotland. Over the centuries, ornamentation became more advanced. One common motif is a snake-shaped dragon. Many runestones have cross ornaments or mentionings of Christ or God, to commemorate conversion to Christianity.

History and mythology

While written sources before AD 1000 were limited, much Old Norse literature has been preserved to posterity; in many case by accident. A skáld was a poet, singer and musician, who could recite long poems from memory, and pass them on to future generations. According to legend they had divine inspiration.

Beowulf is a heroic epic poem set in the 6th century AD, surviving through a manuscript written in AD 1000 in Old English, and part of the English literary canon. Beowulf was a hero living in Denmark, who led his warriors in wars against Sweden. While the plot contains a dragon and other supernatural beasts, the story describes places, tribes and artifacts of 6th century Scandinavia in such a realistic manner that most of the story seems to have been written then and there.

Most Old Norse literature, such as the Edda, an epic poem which contains much of the Norse mythology, as well as the sagas, which describe the history of Iceland, were handed down by oral tradition. They were written down in the 12th to 15th centuries by writers such as Snorri Sturluson, when Old Norse religion and Viking lifestyle had been replaced by Christianity and more organized kingdoms, where the old faith was usually taboo. Parallels to some of the stories in the Edda can be found in the German epic poem Nibelungenlied, highlighting their shared Germanic heritage. These in turn were used as the source material for Richard Wagner's epic opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen.

The word saga has multiple meanings. In both Old Norse and modern Icelandic it means "history", but it is understood as "fairytale" in modern Swedish.

Knowledge gaps have to a large extent been filled by European scholars' knowledge of Greco-Roman polytheism. This however is problematic to an extent as the Romans tried to reconcile several different pantheons (starting with their own and the Greek) by giving them a interpretatio romana and thus (sometimes falsely) equating gods to their Roman ones. Therefore the earliest written records about Germanic tribes, which were written by the Romans, still colour our interpretation of their gods and while there are undoubtedly similarities, they may have become overemphasized first by the Romans and then by classically trained scholars.

Germanic religions were never centralized, but formed a continuum of similar faiths across the northern half of Europe. While Christianity was consolidated in today's Germany by the 8th century, Germanic faiths survived in Scandinavia, some of them until modern times in the form of folklore and legends, albeit with some of the religious elements either removed or Christianised. The Germanic languages, including English, name some days of the week for Germanic pagan gods; Tuesday for Tiw/Týr, Wednesday for Wōden/Odin, Thursday for Thunor/Thor, and Friday for Frīg/Frigg or Freya. The modern name for Christmas in the Scandinavian languages (Jul in Danish, Swedish and Norwegian, Jól in Icelandic and Faroese) was derived from the Yule, the traditional Germanic pagan winter solstice, a term which also survives in English in words like "Yuletide". Some modern English Christmas traditions, such as the Yule log, are also believed to have their origins in the Germanic pagan religion.

Modern revival and fiction

See also: Nordic folk culture

_(2).jpg/440px-A_square_sail_(4912615962)_(2).jpg) Scandinavian scholars have romanticized their prehistory at least since the 17th century, though scientific knowledge of the period was poor. With the rise of nationalism in early 19th century, Scandinavians looked for a common past, adopting Vikings as well as mythological characters as role models. Archaeology and historical research became more advanced, and Old Norse motifs became commonly depicted in Scandinavian art and sculpture; as well as in street names. Richard Wagner's romantic opera cycle Ring of the Nibelung from the 1870s has contributed to the modern world's image of Germanic mythology and Vikings. The Old Norse heritage was an element in the recreation of the modern nations of Norway (independent in 1905) and Iceland (independent in 1944).

Scandinavian scholars have romanticized their prehistory at least since the 17th century, though scientific knowledge of the period was poor. With the rise of nationalism in early 19th century, Scandinavians looked for a common past, adopting Vikings as well as mythological characters as role models. Archaeology and historical research became more advanced, and Old Norse motifs became commonly depicted in Scandinavian art and sculpture; as well as in street names. Richard Wagner's romantic opera cycle Ring of the Nibelung from the 1870s has contributed to the modern world's image of Germanic mythology and Vikings. The Old Norse heritage was an element in the recreation of the modern nations of Norway (independent in 1905) and Iceland (independent in 1944).

Old Norse romanticism was part of the National Socialist ideology, both in Nazi Germany itself, and in subsequent white supremacist movements since the 1980s. While the connection to racism created a taboo around Norse symbolism, most of today's Viking enthusiasts and neo-pagans are clearly anti-racist.

A neo-Pagan community rose in the late 20th century, and Asatru (Beleif in the Æsir) is now a recognised religion. Their practices do not necessarily resemble the true old Norse paganism, and are not taken too seriously. The Norse religion is very much what you make of it. The Viking Age is also a popular theme for reenactment and LARP, and an inspiration for some styles of rock music. The Old Norse and Viking identity is a uniting factor for Nordic Americans, visible as sport mascots in the Midwest.

Since the 19th century, the Viking Age and Norse mythology have been common settings for fiction, each generation with a new interpretation of history. Some classics are the 1825 Frithiofs saga by Esaias Tegnér, and the 1940s Long Ships/Röde Orm series by Frans G. Bengtsson.

Fantasy fiction has been influenced by Norse mythology, from J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, to 21st century works such as Game of Thrones; and even the Marvel Cinematic Universe features the Norse pantheon as American-style superheroes. The Valhalla comic book series, published from 1979 to 1990, has introduced a young audience to Norse gods. The American newspaper comic Hägar the Horrible has been syndicated worldwide; in Scandinavia as well.

The Japan video game industry also draws heavily from Norse mythology, an example being the Final Fantasy series, which draws heavily from the Norse pantheon in naming its characters

The 2010s Vikings TV series was produced in six seasons for Canadian TV Channel History, and is by far the most expensive Viking-themed motion picture. The series has been praised for its sceneries and costumes, but criticized for historical and geographic inaccuracy. It has been recorded in various countries, including England, Ireland, Iceland and Morocco. Beforeigners is a 2019 Nordic Noir series with Viking-age elements in a contemporary setting, mostly recorded in and around Oslo. Assassin's Creed: Valhalla is a 2020 video game that mostly takes place in England.

The Norsemen TV series was shot in both Norwegian (for Norwegian TV) and English (for Netflix) on location in Western Norway. It is a parody and a modern situation comedy set in Viking age context. The humour ranges from splatter to the subtle. The basic premise is that the Vikings' way of thinking, quarreling and talking were just like ours while they were doing the Viking things.

Locations

Pre-Viking Age sites

sites in post-Ice Age Scandinavia (current Denmark, Norway and Sweden) not connected to the Old Norse.

- Ales Stenar (Ale's Stones), Kåseberga (15 km east of Ystad), 55.3825°, 14.054167°. Nicknamed "the Stonehenge of Sweden", a 67 metre long stone ship formed by 59 large boulders of sandstone, a megalithic monument from the Nordic Iron Age, around 600 AD. You can reach the site by car or by bus from Ystad. There are lots of information signs at the parking lot. Walk the 700 metres up the hill from the parking lot and you will reach the stones.

- Alta Rock Carvings, 69.976667°, 23.295833°. A UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Rock Carvings in Tanum, 58.701111°, 11.341111°. A UNESCO World Heritage Site. Carvings have been made during the Swedish Bronze Age.

Viking Age

As Vikings were those Norse people who travelled overseas, settlements in Scandinavia were by definition not Viking towns; though many of them contained artifacts brought home by Vikings.

Sweden

See also: Uppland history tour

- Ale Vikingagård, 57.9441081°, 12.0962372°. A Viking farm. Events throughout the year including feasts and markets in the spring (early May), autumn after harvest time in late October to early November and around Jul, a Norse pagan celebration at Christmas time.

- Birka, 59.3331°, 17.5451°. UNESCO World Heritage site near Stockholm. Birka was established in the 8th century and was an important trading center in the Viking Age. There is a museum on the island of Björkö, including a reconstructed Viking village. Roleplays, guided tours, craftsmen and events throughout the year.

- Foteviken Museum, 55.429281°, 12.953139°. An open-air Viking museum centered around a large Viking settlement reconstruction. The area is an important archaeological site of the Viking Age and the naval Battle of Fotevik was fought around here in 1134. Experimental archaeology, roleplays and season program and engaging activities for the whole family.

- Gamla Uppsala (Old Uppsala), 59.898147°, 17.630196°. Gamla Uppsala is a former settlement outside the modern day city of Uppsala, and was the political and religious centre of Viking-era Sweden. It was once the site of a legendary Norse pagan temple, which brought visitors from all around Scandinavia. The temple was however lost; no-one knows what it looked like, or where it stood exactly. The site also hosts some impressive burial mounds and a large museum.

- Gamla Uppsala museum (Old Uppsala Museum), Disavägen, +46 18-239312. Houses many of the Viking era archeological findings from Old Uppsala.

- Gotlands Museum, 57.63983°, 18.29262°. Though Gotland's Golden Age was during the Hanseatic League years from the 13th century, the island was a commercial centre long before, possibly the home of the legendary Goths.

- Gunnes gård, 59.5083°, 17.9069°. A reconstructed Viking Age farm, mostly open during summer. The surroundings have many runestones, graves and other genuine artifacts from the Viking Age and earlier. A market fair is held annually in early autumn.

- Gustavianum, 59.8576679°, 17.6319031°. It is the university museum of Uppsala University, and among other things it exhibits findings from Vendel- and Viking-era boat burial field in nearby Valsgärde (see below).

- Järnåldershuset i Körunda, 59.0080°, 17.8834°. A reconstructed Viking Age longhouse.

- Medeltidsveckan (Medieval Week), 57.6396467°, 18.292476°. While conversion to Christianity in the 11th century marked a divide between the Viking Age and the Middle Ages, Gotland remained a decentralized land of peaceful mariners and merchants (farmaðr, farmän) instead of warmongering Vikings, until Sweden annexed the island in the 17th century. Stil, this festival week creates a Viking-like atmosphere.

- Rök Runestone, 58.295°, 14.7754°. The world's largest runestone, and the oldest known written record in Sweden. The name of the village Rök has the same roots as rock (named for the stone), which means that Rök Stone is a tautology.

- Sandby borg. An Iron Age ringfort. Extensive research during the 2010s has revealed that a massacre took place here in the late 5th century AD. Known as Sweden's Pompeii. 2021-05-23

- Stallarholmen Viking Festival, 59.357222°, 17.205833°. Annually the first weekend of July, in a village with plenty of runestones and other Viking-age artifacts.

- Stavgard, 57.2185°, 18.5299°. A 10th-century village ruin where the master house was 60 metres long, and a modern replica of the village.

- Storholmen, 59.832017°, 18.649877°. A reconstructed Viking village situated on the shore of lake Erken. A small nature reserve of Norr Malma to the south, including a large graveyard from the Iron Age. The whole region – known as Roslagen – is steeped in history. In the Viking Age there was important trade with the East. There is a nice 18th-century inn and restaurant nearby and a child-friendly lakeside beach.

- Swedish History Museum (Historiska Museet), 59.33471°, 18.09094°. Describes Swedish history from the Ice Age to present day, with emphasis on the Middle Ages (1000-1500). The Gold Room has gold treasures from the Bronze Age to the 16th century. Since 2021, the museum has the world's largest Viking Age exhibition, World of Vikings, where artifacts describe the society and faiths of the Viking Age.

- Trelleborgen, 55.37624°, 13.14756°. One of only seven known Viking Ring Castles from the 980s. "Trelleborg" is the name of the town, the castle and a general term for Viking Ring Castles. It is 143 metres in diametre and was largely reconstructed with palisades and houses in 1995. Activities for all ages with museum building, store and café. Watch role plays and re-enactments or engage in the Viking market, changing events or Viking board games. Stories from Norse mythology are occasionally dramatised here, but only in Swedish.

- Uppåkra Arkeologiska Center (Uppåkra Archaeological Centre), 55.666983°, 13.172272°, +46 70-825 49 60. A historical museum by and about the Viking-era archaeological site Uppåkra. This area was supposedly a cultural and religious centre in Scania with a pagan temple, but was abandoned in favour of modern-day Lund around the year 990.

- Vikingaliv, 59.326556°, 18.094775°. A Viking museum opened in 2017. The main attraction is Ragnfrids saga, an 11-minute dark ride through dioramas depicting a Viking adventure. There is also a (rather small) hands-on exhibition with replicas of Viking craft. Good for visitors who want a brief introduction to the Vikings and are not bothered by the cover charge or the absence of genuine artifacts.

- Valsgärde, 59.926111°, 17.626389°. At the bank of Fyris River, there is a small moraine hill which does not look like much to the eye. However, it covers one of the most important Viking-era archaeological site ever excavated. Between the 5th and 11th centuries AD, this site was used as a burial site. Archaeologists have discovered some 90 graves, including 15 lavish boat burials. Since the same site was used continuously for such a long time period, archaeologists use its findings to compare how the same culture developed over time. Today, there are no noticeable remnants at the site. These can be found at the University museum Gustavianum, in central Uppsala. However, you can still visit Valsgärde to appreciate its beautiful landscape and historical atmosphere. 2018-09-02

- Värmlands vikingacenter. A Viking village.

- Vikingatider, Ådalsvägen 18, SE-246 35 Löddeköpinge (at the village of Löddeköpinge near Lund, some 20 km north of Malmö by E6), 55.759979°, 13.026299°. May to September. An archaeological Viking-themed open-air museum and landscape with Viking houses and farms. Engage in everyday activities of the Vikings at the farm or in the workshops. Guided tours (in English) of the settlement and surrounding landscape and special events throughout the year, including re-enactments, craftshops and markets.

- Årsjögård, 60.52648°, 16.75226°. An open-air museum centered around a reconstructed Viking farm in the midst of a historic region known as Järnriket (The Iron Realm). Experimental archaeology and occasional role plays, re-enactments, feasts, music and crafts. Learn more about the cultural history of this area, in particular the Viking Age. The Sörby gravefields with 90 burial mounds and stone settings are nearby, as are the popular lakeside bathing site of Strandbaden at the lake of Storsjön, locally known as "Gästriklands riviera". At Strandbaden you will find a camping site and restaurant.

- Eketorp, 56.295525°, 16.484954°. An old fortification stemming from the middle ages with activities for children.

Iceland

- 871±2 (The Settlement Exhibition), Reykjavík, 64.14735°, -21.942814°, +354 411 6300. Run by the Reykjavík City Museum, this exhibition in central Reykjavík was built around the oldest archaeological ruins in Iceland. As the name indicates, these ruins date to around the year 870. This interactive exhibitions brings you the early history of the area that today forms central Reykjavík.

- National Museum of Iceland (Þjóðminjasafnið), Reykjavík, 64.14194°, -21.94805°, thjodminjasafn@thjodminjasafn.is. This museum by the University of Iceland campus takes the visitor through the history of a nation from settlement to today. Includes a café and a museum shop. 2015-07-09

- Reykjavík City Museum (Árbæjarsafn), Kistuhyl, 64.1184°, -21.8185°. In the suburb of Árbær, and frequently called Árbæjarsafn (Árbær museum), this open air museum contains both the old farm of Árbær and many buildings from central Reykjavík that were moved there to make way for construction. The result is a village of old buildings where the staff take you through the story of a city. The staff are dressed in old Icelandic clothing styles and trained in various traditional techniques, for example in making dairy products or preparing wool.

- Þingvellir National Park, 64.2556°, -21.1284°. The place where the Icelandic parliament (Alþing) met for a few days every year from 930 until 1798. This yearly event also served as a supreme court and a huge market and meeting place for people from all over the Iceland. 2018-01-01

- The Settlement Centre, Borgarnes, 64.5357°, -21.9232°. A media centre showcasing the Viking sagas, stories or descriptions of their everyday life. 2018-02-16

- Eiríksstaðir, 65.0586°, -21.5496°. An open air museum, centred on the recreation of the homestead of Erik the Red and his son Leif Eriksson (considered to be the first European to set foot in America). 2018-02-16

- Saga Centre, 63.7517°, -20.2217°. A museum showcasing Njals Saga, the main saga of the Icelanders. 2018-02-16

- Snorrastofa, 64.7036°, -21.1212°. A museum and research centre showcasing Snorri's Saga, written by the 12th- and 13th-century writer Snorri Strulasson. 2018-02-16

- Viking World, 63.976°, -22.5289°. A museum with five Viking exhibitions, including a replica of a ship. 2019-06-20

Norway

- Lofotr Viking Museum (Lofotr Vikingmuseum), Bøstad, 68.24°, 13.7531°. Located on the island of Vestvågøya in the Lofoten archipelago, is a huge reconstructed Viking Chieftains hall in a dramatic landscape. The hall holds exhibitions and there are walking paths in the surrounding landscape. Seasonal events and programs with roleplays, Viking feasts, Viking Festival and more. Animals and a smithy. In the summer it is possible to sail with a Viking ship replica nearby.

- The Viking Ship Museum (Vikingskipshuset), Oslo (on the island of Bygdøy), 59.904945°, 10.684408°. All year. The main attractions here are the Gokstad, Oseberg and Tune Viking ships, all originals. The Viking Ship Museum is part of Museum of Cultural History, itself a department of University of Oslo (UiO). Museum of Cultural History also houses Historical Museum with a permanent exhibition themed around the Norse and Vikings in particular. Tickets include admission to both museums within 48 hours. The Bygdøy island can be reached by road or ferry (in the summer).

- Gokstad Mound (Gokstadhaugen), 59.140759°, 10.253125°. The burial mound at Gokstad where the Gokstad ship was discovered in 1880. The ship is the largest found in Norway and is now on display in the Viking ship museum, Oslo. The Norwegian government has asked UNESCO to include the mound on the world heritage list.

- Stiklestad, 63.796111°, 11.558611°. Site of the battle in year 1030 where King Olav died. 2016-08-09

- Trondenes historical center, Trondenesveien 122, Harstad, 68.8203°, 16.5592°. Displaying more than 2,000 years of history in the region, which was a Viking power centre (Tore Hund from Bjarkøy just north of Harstad killed St Olav at the Battle of Stiklestad, according to the saga). 2018-02-16

- Three Swords, 58.9413°, 5.6720°. (Sverd i fjell, literally Sword in Mountain), a monument outside the centre of Stavanger, beside the Hafrsfjord. The swords themselves are massive and in the background is the fjord. The monument commemorates the battle of Hafrsfjord in the late 800s where Harald Hårfagre beat his eastern opposition and became the first King of Norway. 2018-02-16

- Midgardsenteret (Borrehaugen), Borre (Horten), 59.3848°, 10.4668°, +47 33 07 18 50. New museum about history, religion and wars of the vikings, next to Borrehaugen, the viking cemetery. Cafeteria.

- Kaupang, 59.0341°, 10.1068°. Around 800 AD a Viking trade post was established here, and today it is both an archaeological site and a venue for Viking events in the summer. 2018-02-16

- Bronseplassen, 58.1495°, 8.1638°. Reconstructed houses from the Bronze Age and Viking times in Høvåg, approx. 15 km west of Lillesand. There are also bark boats, labyrinth, offering space and cemetery. 2018-02-16

- Avaldsnes, 59.353533°, 5.303384°. A former Viking settlement, nowadays featuring a Viking farm, a history centre, burial mounds and archaeological excavations. 2018-02-16

- Gulen assembly (Gulating), Eivindvik (Sognefjorden), 60.98177°, 5.07521°. Gulating was the viking era legislative assembly and high court (þing) for West Norway. The site had a central location along the shipping lane (the highway of the time). The assembly may have been established by Harald Hairfair around year 900 (perhaps older), and existed until 1300. The Gulating law was the corresponding legislation and at its widest extent covered West Norway as well as Agder counties, Valdres and Hallingdal. The Gulating law originated around 900 (or earlier) is Norway's oldest known legislation and was in effect until 1688 (some rules are still relevant). Originally Gulating was a "common assembly" where all "free men" joined for the annual meeting, later only delegates from each district. Around year 1300 the assembly met in Bergen rather than Gulen. Today the name is retained in Gulating court of appeal in Bergen. Two ancient stone crosses mark the original site, and new monument marks a later site nearby. Similar assemblies and laws existed for Trøndelag and for Eastern Norway. When Norway's modern constitution was crafted in 1814 the name Storting (grand assembly) was adopted.

- Frosta assembly (Frostating), Frosta (Trøndelag), 63.590833°, 10.741389°. Frostating was the Viking era court and general assembly for the Trøndelag area, similar to Gulating for Western Norway. The "Thing hill" is marked and can be visited.

- Hæreid burial mounds, 60.4635646°, 7.0919275°. Several hundred burial mounds from Viking age and earlier. The largest such burial field in Western Norway, one of the largest in Norway.

- Myklebust viking ship (Myklebustskipet). Traces of a 25-m-long Viking ship were uncovered in a burial mound at Nordfjordeid in 1874. Presumably one of the largest Viking ships found. A replica was completed in 2019 and is on display in the village.

Denmark

- Bork Vikingehavn, 55.837°, 8.2661°. Viking village and harbour area with Viking ship replicas and a town market. Re-enactments and roleplays that varies throughout the year. Great with kids. 2017-01-01

- Fyrkat, 56.623333°, 9.770556°. Viking Ring Castle and re-constructed Viking houses. Sometimes roleplays and craftsmen. 2016-08-14

- Jelling Monuments, 55.755833°, 9.419444°. UNESCO World Heritage Site in Jelling, a Viking Royal residence. Enormous stone ship monument, burial mounds, runestones and 10th century church. Newly built exploratorium bringing the site's rich history to life. Good for all ages. Free 2017-01-01

- Lindholm Høje, 57.077222°, 9.9125°. Pagan Iron Age and Viking Age burial grounds with hundreds of stone-set grave sites. Museum building. 2016-08-14

- Ribe Vikingecenter, 55.310278°, 8.7661118°. Late April to October. Large Viking centre and open-air town museum reconstructed at the former site of a large Viking town. Re-enactments, craftsmen, roleplays and experimental archeology of varying themes throughout the year. Ride Icelandic horses, help the farmers, watch the falconry displays, shoot with bows or learn to fight like the Vikings; there are many activities here suited for all ages and interests. 2016-08-14

- Sagnlandet Lejre, 55.615833°, 11.9425°. Large open-air Viking and pre-historic center with themes reaching back to the Stone Age as it unfolded in Scandinavia. Located in Lejre, a former royal homeland in the Nordic Iron Age and early Viking Age. Engaging activities for all ages. 2016-08-14

- Trelleborg Castle, 55.39405°, 11.26501°. A Viking Ring Castle, one of only seven known of its kind. Small museum and some reconstructed Viking buildings. DKK 100 2015-07-25

- Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde (follow the signs from the cathedral), 55.641476°, 12.080422°. A museum with several original Viking ships, a viking research centre, a harbour with copies of viking ships, and a shipyard making new ships. Study the originals, watch how archaeologists preserve them and engage on a small sea-voyage with replica ships in the summer months.

- Aarhus Viking Museum, 56.1566°, 10.2089°. Small Viking museum located across from the cathedral in the basement of the Nordea Bank. The museum focuses on local history during the Viking Age and most of the displayed items were excavated on site. If you are interested in Viking Age history in general, visit the large Moesgaard Museum (MoMu) south of the city.

- The World of the Frederikssund Vikings (Vikingernes Verden i Frederikssund), 55.82887°, 12.05780°.

Germany

- Haithabu (Hedeby), 54.491578°, 9.564283°. Located at the southern end of the Jutland peninsula, Haithabu was once the site of the largest Viking town in Scandinavia. Now an open-air town museum with reconstructed Viking houses. Experimental archeology, craftsmen and engaging roleplays and reenactments of the former life in the Viking Age town. Together with the Danevirke defensive walls and trenches nearby, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2018. 2017-01-01

- Danevirke, 54.4831°, 9.4982°. Literally meaning the Earthworks of the Danes, the first of these walls were constructed already around 500 AD as a protective wall against the south. A few centuries later, it was expanded by the Vikings into a system of trenches and walls. Interestingly, the Danevirke was used in the war against Prussia in 1864 when the Danes lost the area. 2018-07-02

Greenland

- Norse settlements in Greenland, 61.15°, -45.516666666667°. Vikings settled parts of Southern Greenland, starting with Erik the Red, who gave the landmass its name to make it sound appealing to travellers. Remains and reconstructions of the Norse settlements can still be visited, some of them forming a world heritage site. 2017-09-03

Canada

- L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, 51.595267°, -55.531222°. Archaeological site featuring the remains of the North American Viking settlements described in the Vinland Sagas: depressions in the ground that were once the foundations of houses, a sod longhouse reconstructed according to Viking-era building methods, plus some unearthed artifacts displayed in the museum contained in the visitors' centre. Guided tours and occasional special events.

- Norstead, 51.600628°, -55.526289°. Just down the road from L'Anse aux Meadows, Norstead takes a more interactive, living-history approach to the subject of the Norse incursion into North America, with a "village" of reconstructed longhouses populated by costumed interpreters reenacting daily life in a 12th-century "Viking port of trade" with a respectable degree of historical accuracy.

Latvia

- Grobiņa Viking Settlement, Skābaržkalns, Grobiņa, close to Liepāja, 56.5330621°, 21.1639451°. The west coast of Latvia has Viking heritage, where there was once a settlement named Seeburg (now in Grobiņa city).

United Kingdom

- Jorvik Viking Centre, 53.957778°, -1.080556°. The Jorvik Viking Centre is a must-see for visitors to the city of York and is one of the most popular visitor attractions in the UK outside London. Jorvik Viking Centre invites visitors to journey through the reconstruction of Viking-Age streets as they would have looked 1000 years ago. 2019-07-21

- Lindisfarne, England, 55.678056°, -1.795556°. An early Christian monastery at the Northsea rocky shore. The Norse raid at Lindisfarne in AD 793 usually marks the beginning of the Viking Age.

- Up Helly Aa, 60.3038°, -1.2689°. Europe's largest and most famous fire festival. It takes place on the last Tuesday in January. Over the year the 'Guizer Jarl' or Viking Chief and his squad prepare costumes, weapons and a replica heraldic style Viking Galley and torches. There is a torchlight procession of over 800 participants and then the Galley is ceremoniously burned. Tickets to the halls are by invitation only, but public tickets are available for the Town Hall from the committee. Although the Lerwick festival is the largest and most famous, eleven other fire festivals are held across the islands.

Ireland

- Dublinia (Viking Museum). Exhibition of life in the Viking settlement and medieval city, child-friendly.

The Normans

- Battle Abbey and site of the Battle of Hastings, 50.91496°, 0.48483°. Now maintained by English Heritage, the Abbey was established after 1070 on the site of the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the Pope having decreed that the Norman conquerors should do practical penance for the deaths inflicted in their conquest of England. William the Conqueror initiated the building, but it was only completed and consecrated in 1094 in the reign of his son William II (Rufus). The Abbey is in an incomplete, partly ruinous state, having been dissolved during the Reformation, then re-used as a private home. Visitors can stand on the reputed site where Harold was slain on 14 October 1066.

- Bayeux, 49.2794°, -0.7028°. A cathedral town which features the Bayeux tapestry, which chronicles the Norman invasion of England, culminating in William's victory over Harold in 1066.

Russia

- Staraya Ladoga, Russia. According to some sources, this was where Rurik first founded his kingdom before later moving his seat of power to Novgorod.

- Novgorod, Russia. According to some sources the first capital of Rus', the kingdom which modern-day Russia, Ukraine and Belarus claim their origins in. Rurikovo Gorodische, about 2 km south of the modern city centre, is said to be the site where Rurik the Viking chieftain founded the kingdom of Rus'. However, Novgorod's stint as the capital of Rus' would be short-lived, as Oleg of Novgorod, Rurik's son and successor, would move the capital to Kiev after conquering it, thus giving it the name which it is most commonly known as today, Kievan Rus'.

See also

Related Wikipedia article: Vikings