Scuba diving is an activity in which you swim underwater for extended periods using self-contained underwater breathing apparatus, hence the acronym scuba. It's become so popular for recreation that in most contexts the simple term "diving" is synonymous with scuba-diving, and is so used on this and related pages.

Understand

Holding your breath and plunging underwater is an activity as old as humanity, and may be among the first evolutionary developments to distinguish us from the other apes. Already by the 4th century BCE diving bells were in use, by the 16th century CE these had renewable air supply pumped down from the surface, and in the 18th / 19th century the bells were miniaturised into the classic "deep-sea diver" outfit of bulbous helmet, massive boots, and snaking supply hose. The 20th century saw self-contained breathing equipment develop for marine engineering and warfare, as well as for dry-land applications such as fire-fighting and mining rescues. Along with the mechanical advances came better scientific understanding of how diving affected the body, and how its harms could be minimised. These mechanical, industrial and scientific advances continue today, and paved the way for human spaceflight, but in the middle to late 20th century scuba diving expanded into a recreational activity. Pioneers and explorers like Jacques Cousteau and Hans Hass were succeeded by a mass market seeking kit, training, and dive-related resorts and travel, just for the fun of it. Entire nations now depend on diving tourists for their livelihood.

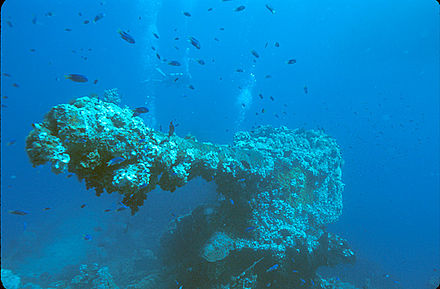

Why bother? - for the view, the activity, the excuse to travel, and - let's not deny it - the technical challenge. The view is literally an immersive experience. You see terrain and wildlife like nothing on land. Fish allow you to approach much closer than wild land animals will, and the coral life is exotic. It's a surreal, dreamy virgin forest, undeveloped and unfarmed yet maybe within yards of a major highway, where most of the things that look like flowers and ferns are actually bizarre animals. The best of it is usually relatively shallow, where there's sunlight and colour. Deeper down lie wrecks, torn and sculpted by their sinking and by later sea action, often with dark histories. The activity is that you'll be spending your day out on the water, often in great surface scenery, with all the business of getting into and under and subsequently out of the water and back to port. It's seldom aerobically challenging but will leave you ready for an early night, and if diving doesn't improve your mental wellbeing and outlook on life, then maybe it's your mobile phone or job that ought to take a dunk as deep as yours. Travel is a major part of it, since few of us live next to a good dive spot - some destinations and considerations are described below. And there's a challenge even in simple recreational diving, far from the areas that are considered "technical diving", because you're doing things that astronauts have to learn. Configuring and checking your kit, computing air requirements versus depth and time limitations, navigation on the surface and below, and thinking through "what if?" scenarios. You're preparing to venture out to interact with alien life-forms, starting with the motley group of fellow-divers and crew on the dive boat. It's a mental, physical and cultural work-out.

Learn

Is it for you? You don't need to be a strong swimmer or super-fit, but you do need to feel comfortable in the water. Diving will from time to time get you slapped in the face by sea water, which will also get in your eyes, mouth, and any expensive "water-proof" watch or camera you've brought along. If you can cuss and carry on, well done; if the prospect panics you then stay on the glass-bottom boat. If you have long-term medical conditions like diabetes these need to be very well controlled. Check the medical questionnaire on the websites of the training agencies (listed below). Most people will be fine, with no amber- or red-light responses; a few may need personal medical assessment, advice and sign-off from a doctor; and some people must accept that they shouldn't dive.

Learn to snorkel and buy your own mask and fins. It's not a necessary preliminary, but gives you a good start. Skills you quickly learn from other snorkellers are how to keep your mask clear of water and mist, how to equalise the pressure in your ears on descent, and how to fin along gracefully and economically, without looking like a bear trying to unicycle. Snorkelling will make you more familiar with marine life - much of it is in the shallows, where the light is best - and create an easy holiday activity option. A mask needs to be a good fit, and if you need prescription glasses to read your watch then get prescription lenses fitted to your mask. Fins - proper open-water fins not kiddy-pool flippers - should be chosen for comfort, not for bombastic ads about performance. Mask and fins are all you should buy at this stage, they're inexpensive and lightweight, and your own stuff will suit you better than rental kit.

.jpg/440px-El_Gouna,_Egypt_-_November_2012_(8181765020).jpg) Take a training course with a competent, recognised training agency. This is crucial: you must acquire certain basic skills, and understanding of what the underwater environment is doing to your body, to avoid serious harm. (In some ways you're at greater risk in the shallows, as the training will help you appreciate; it's not all about "the bends" down in the depths.) A common preliminary step is to do a "try-dive", then set aside 3 to 5 days for the course, preferably in a pleasant warm resort. The course will involve classroom teaching, book- or e-learning, "dry" skills eg kit assembly, pool dives, then a few sheltered sea dives. This should result in a novice compliant with at least international standard ISO 24801-1 qualification recognised world-wide - no point getting some flaky local diploma only recognised by its issuer - and a log book (they're still on paper). You're then qualified to make "open water" dives (ie not just in a pool) but only if accompanied by a dive-buddy of instructor or divemaster status. No big problem if you can only get part way through the course: they'll issue a "referral" note whereby you can later pick up where you left off at any dive school affiliated to the same training agency. An entry level qualification to ISO 24801-2 standard is more widely accepted and you will not need to be personally escorted by a professional on every dive.

Take a training course with a competent, recognised training agency. This is crucial: you must acquire certain basic skills, and understanding of what the underwater environment is doing to your body, to avoid serious harm. (In some ways you're at greater risk in the shallows, as the training will help you appreciate; it's not all about "the bends" down in the depths.) A common preliminary step is to do a "try-dive", then set aside 3 to 5 days for the course, preferably in a pleasant warm resort. The course will involve classroom teaching, book- or e-learning, "dry" skills eg kit assembly, pool dives, then a few sheltered sea dives. This should result in a novice compliant with at least international standard ISO 24801-1 qualification recognised world-wide - no point getting some flaky local diploma only recognised by its issuer - and a log book (they're still on paper). You're then qualified to make "open water" dives (ie not just in a pool) but only if accompanied by a dive-buddy of instructor or divemaster status. No big problem if you can only get part way through the course: they'll issue a "referral" note whereby you can later pick up where you left off at any dive school affiliated to the same training agency. An entry level qualification to ISO 24801-2 standard is more widely accepted and you will not need to be personally escorted by a professional on every dive.

Build your experience, skills and kit. As and when you can, but an important next step is a follow-on course to what's variously called "rescue", "advanced" or "sport" diver. That means you have the skills to bail out your dive-buddy if he / she gets into difficulties. So you can make a buddy-pair with someone at your own level, and most holiday resort dive trips will now be within your range, but err on the side of caution. There are many further qualifications you could take, e.g. marine-life identification, but there's a lot of catch-penny merchandising of such courses. The most important qualification is the accumulating wisdom between your ears, not something pasted in your log book. Above all, enjoy your diving while staying safe. Ask around about what sort of kit, if any, to buy considering your likely pattern of diving: for occasional resort dives, rental is fine. If you do intend to buy, an early purchase is a capacious dive-bag, to put it all in and keep wet stuff away from the dry. The next cycle of purchase is the BCD ("buoyancy control jacket"), the regulator to breathe from, and wetsuit to keep you warm; perhaps a few accessories such as dive gloves. That's all you need for a dive trip; they're not cheap, but should last for many years and defray the cost of renting. Only buy air tanks and weights if you'll be diving in your own locality, since these can't travel by air.

Go deeper into advanced and technical diving. The latter could be roughly defined as "anything that was edge-of-the-possible 20 years ago, is fairly common nowadays, and will probably be included in basic training in another 10 years." Some avenues are:

- Dry suits: essential for diving in cold water. You have to buy your own because they must fit precisely so, otherwise the neck seal either garottes you or lets in gouts of freezing water. You need training to use them, and a few simple test-dives under supervision.

- Underwater cameras: are best deferred until you're trained, because they're a major task-loading and distraction from other safety-critical stuff that you don't yet do automatically. That said, it's far easier to teach a photographer to become a competent diver, than to teach a diver to become a competent photographer.

- Mixed gas: this friendly air that you depend upon and breathe from scuba tanks, at greater depth will poison you or give you decompression sickness on the way up. Other gas mixtures reduce these risks, eg Nitrox which has a higher percentage of oxygen than the 21% in air.

- Rebreathers: in conventional "open-circuit" scuba, what you breathe out still contains oxygen but just bubbles away to the surface. Rebreathers instead capture your exhalations, scrub out the carbon dioxide, and recycle the oxygen and nitrogen. So they greatly extend dive times, but they're expensive, and can kill their users even when used carefully.

- Hostile environments: anything deeper than 40 m / 130 ft is beyond standard recreation. Environments that are hostile even when shallow are icy waters, caves, and the interior of wrecks. Touring a shipwreck from the outside is easy, and so is going inside - but getting out again? When the viz has gone because you've kicked up silt, your air supply and torch are failing, and you've lost contact with the person who led you in?

- Instruction and careers: a great way to enhance your own skills is to teach them to others. But becoming an instructor or dive-master is a major commitment of time and money, it's not a cushy way to practise your hobby. The job market is flooded with wannabe instructors who are skilled and committed, but just working for tips and taking side jobs to get by. They have to ply their trade day in day out, and may struggle to remember when diving seemed like fun. They may be in a vulnerable position, working "off the books" in a country with lax labour laws and no protection, but the immediate foreign scapegoat if anything goes wrong. As for commercial diving, that's never ever been fun, just hard graft in a cold dark place, and career opportunities are dwindling as ROV and robot capabilities develop.

Destinations

Two-thirds of this planet are covered by water; there are 193 sovereign member states of the UN, and most (even the landlocked) have scope for diving of some kind. There are scores more dependencies, territories and uninhabited islands with diving prospects. The only nations listed below are those that you might visit for the purpose of diving, because they have dive sites worth travelling to visit plus enough infrastructure for general travel and for recreational diving. Divers of the great frontiers (such as Antarctica) praise those sites, but expedition diving is beyond the scope of this page. For each country, only the key features (e.g. seasonality) and standout sites are mentioned here. More information may be found on country- or region-specific diving destination pages and dive-site subpages, and on "Do" listings for regions and destinations. The country and city destination pages are the main place to find out how to get there, where to stay and eat, and other things to see and do there.

Your key decision (before budget & time comes into it) is whether the trip will focus on diving, or if it's to be one of several activities in an all-round vacation. A beginner should focus: you need to commit to a week in a single resort to complete a training course, bearing in mind that there might be a day lost to the weather, and that you're advised against flying within 24 hours of diving. If you travel with a non-diving partner, their comfort and amusement affects the choice of resort. An experienced diver may be content with a day or so (and in the Med, frankly that's plenty) between touring the antiquities and other attractions. If so, he / she won't bother lugging kit, but will rent from the dive centre. Or if more extended diving is the point, consider a liveaboard boat, which sails for several days around sites beyond the range of day-boats.

Africa

Africa has a long coastline, with coastal waters ranging from the warm tropical Red Sea, to the cool temperate west coast of southern Africa. The east coast of Africa has better developed diving than its west or Mediterranean coasts, with destinations scattered all the way from Egypt to South Africa, wherever accessibility and political stability allow.

The infrastructure varies enormously and is constantly changing - not always for the better. Egypt and South Africa are among several that have Nitrox, for example, yet others may not even have medical oxygen. Emergency medical facilities vary from world class to non-existent. Don't assume that anything is available at any specific destination. Ask and get written confirmation or book through certified operators and agents.

(For the Canary Islands see Europe, as they're part of Spain though set in the Atlantic off Morocco.)

Djibouti

Djibouti has a unique ecosystem where the mix of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean results in an abundance of marine life. Between the months of September and January Djibouti is home to resting migrating whale sharks. It is common to see many whale sharks, including juveniles, which tend to stay close to the coast during their visit.

Seven Brothers Islands is a major attraction to Djibouti waters. This breathtaking reef system is north of the Devils Cauldron, and comprises seven islands covering a vast area. Monumental drop-offs with stunning soft corals carpeting the walls, schooling fish and big pelagics can all be expected.

Egypt

Egypt has good diving in the Red Sea, both along its African shore (the biggest resort being Hurghada) and in the Sinai peninsula (mainly at Sharm-el-Sheikh, plus smaller Dahab). It's a year-round destination, but is especially popular with Europeans in winter; in summer the desert heat is fierce. The diving is good for all ranges of ability, from beginners to tekky stuff. Diving is by boat, as the reefs are too far out for shore diving. The main resorts are also bases for liveaboard cruises, to reach the many wrecks and reefs beyond the range of day-boats. Egyptian liveaboards even sail to Sudan, and this is the main way to dive in that country, though a Sudan visa is still necessary. It's also possible to dive Egypt's Mediterranean coast off Alexandria, but conditions are tougher and there's less to see. Cheap internal flights and long-distance taxis mean that diving in Egypt can easily be combined with seeing the antiquities of Cairo, Luxor and elsewhere.

Egypt has good diving in the Red Sea, both along its African shore (the biggest resort being Hurghada) and in the Sinai peninsula (mainly at Sharm-el-Sheikh, plus smaller Dahab). It's a year-round destination, but is especially popular with Europeans in winter; in summer the desert heat is fierce. The diving is good for all ranges of ability, from beginners to tekky stuff. Diving is by boat, as the reefs are too far out for shore diving. The main resorts are also bases for liveaboard cruises, to reach the many wrecks and reefs beyond the range of day-boats. Egyptian liveaboards even sail to Sudan, and this is the main way to dive in that country, though a Sudan visa is still necessary. It's also possible to dive Egypt's Mediterranean coast off Alexandria, but conditions are tougher and there's less to see. Cheap internal flights and long-distance taxis mean that diving in Egypt can easily be combined with seeing the antiquities of Cairo, Luxor and elsewhere.

Kenya

Coastal Kenya has five marine parks protecting its fringing coral reef. Average sea temperatures range from 25°C in August to 30°C in March, and April and May are the wettest months. The sea is calmest from October to March, whale sharks and manta rays visit between November and February, while humpback whales can be seen from July to October.

Madagascar

Madagascar's most reliable good diving is off the northern isles of Nosy Be and Nosy Tankiley. It's possible further south along the west coast e.g. at Toliara, but in the hot rainy season Nov-April the deluge of muddy water from the rivers spoils the viz.

Malawi

Malawi is a landlocked country, but it has a long coastline on Lake Malawi, with good freshwater diving.

Mauritius

Mauritius is completely encircled by a coral barrier reef and is home to many sponges, sea anemones and a variety of multi-colored tropical reef fish such as the Damselfish, Trumpetfish, Boxfish, Clownfish and the Mauritian scorpionfish with its unique orange color. Most of the dive sites are on the west coast around Flic-en-Flac, in the north, at Trou aux Biches or at the Northern Islands. Besides the coral reefs, there are ship wrecks dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries, and ships sunk more recently which create beautiful artificial reefs. The best time to go diving is from November to April when the visibility is very good.

Mozambique

Mozambique is on the southeast coast of Africa. It has a tropical climate with a wet season from October to March and a dry season from April to September. Rainfall is heavy along the coast and decreases in the north and south. Cyclones are common during the wet season. Water temperatures are tropical, ranging between 29˚C in summer and 22˚C in winter, and will seldom be below 24˚C, and visibility can range from 8 to 40 m. Diving is year round, but the drier winter is more comfortable, with fewer mosquitos. The marine ecology is the highly diverse Tropical Indo-Pacific. A wide range of reef building corals, and other coral types can be found here, along with a diverse and colourful fish and invertebrate fauna sharing the shelter and habitat provided by the corals. The region is particularly known its abundance of manta rays, reef sharks, whale sharks and humpback whales.

Seychelles

The Seychelles are a group of 115 islands, only a few inhabited, in the Indian Ocean that lie off the coast of East Africa, northeast of Madagascar. Scuba diving is popular and can be done almost anywhere in Seychelles. Nitrox is available at a limited number of outlets at around €8 per fill. Diver training is available at various schools.

Diving is possible all year round. The best diving conditions are usually in March, April and May and September, October and November, as these months are when seas are calmest. Visibility can be over 30 m and water temperatures reach 29 °C. Rain, algal blooms, and winds can affect the diving conditions. The Seychelles are not greatly affected by tropical cyclones.

Sites vary in depth and are mostly moderate depth — from 8 to 30 m. Conditions at most sites are suitable for divers of all skill levels. The inner island reefs are basically granite formations, supporting soft and hard corals. Offshore dive sites are suitable for more experienced divers and provide a chance of an encounter with whale sharks and giant stingrays. There are also some wreck sites.

South Africa

The south coast has a large number of wrecks and the highest diversity of endemic species on temperate rocky reefs. Diving in this region is very weather-dependant and visibility often limited. The annual sardine run through the south coast to the east coast has huge baitballs and a large variety and number of predators. Another annual event in this region is the Chokka spawning, near St Francis Bay.

The east coast diving destinations are spread along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal from the tropical coral reefs and coelacanths of Sodwana Bay in the iSimangaliso Marine Protected Area, through the subtropical rocky reefs and wrecks of Durban, the sharks of Aliwal Shoal to the Protea Banks at Margate.

The inland dive sites include fresh water dives in sinkholes and abandoned mines at altitude, variously used for training, deep technical and cave diving.

Sudan

Sudan has good diving in the Red Sea near Port Sudan, either from coastal resorts or on live-aboards (which also visit from Egypt). Water temperature varies from 20°C (68°F) in Feb/March to 28°C (82°F) in Aug / Sept. From November to February it's windy and the sea gets rough.

Tanzania

The best known diving region of Tanzania is at the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, but the less known Mafia Island south of Zanzibar and some parts of the mainland coast also have good dive sites.

Asia

Scuba diving destinations in Asia are mostly concentrated in the Middle East and South East Asia, where the water is warm and visibility is usually good. These regions mostly have a diverse tropical Indo-Pacific coral reef ecology, and there are a number of notable wreck diving sites. Where tourism is a major industry, scuba facilities abound, and this is generally a pleasant place to learn to dive, and a good region to see a lot of marine life. The attitude towards conservation is variable, and in some places the reefs have been severely impacted by unsustainable fishing methods.

Brunei

Brunei offers some great diving, and is one of the best places in SE Asia for macro photography. In addition to coral and fish, there are several shipwrecks and many species of nudibranch. Water temperature is generally around 30°C and visibility is usually in the 10- to 30-m range, although this can reduce during the monsoon season. As diving in Brunei is not overly developed, the sites, and especially the coral reefs, are unspoiled and in pristine condition.

Burma

Myanmar or Burma has been slow to open to tourists and has little infrastructure. However, liveaboards from Phuket in Thailand visit the Mergui Archipelago in the far south of Burma. The best diving conditions are from December to April, with whale sharks and manta rays visiting from February to May.

Egypt

Egypt is partly in Asia, but see Diving in Egypt for dive sites on both sides of the Red Sea.

India

India's coasts have tropical climates. Pondicherry’s peak season is January through June and then September through November, although diving in this area may be done all year long. The water temperature varies between 27°C/80°F and 30°C/86°F. The average annual temperature across India is 25°C/77°F. Many of the dive sites more popular with tourists are around the offshore island territories such as the Andaman and Nicobar islands and the Lakshadweep Islands which have clear oceanic water.

Indonesia

Indonesia is the biggest archipelago nation in the world with more than 18,000 islands. It offers diverse diving experiences, from tourist-trippy Bali to extreme wilderness, and with a remarkable mix of marine life. Highly rated dive areas are Raja Ampat, Alor and Komodo.

Israel

Israel has three seas: Red, Med and Dead. You only want to dive in the Red, a 4-km stretch of coast by the city of Eilat, sandwiched between the Egyptian and Jordanian borders. It's easy reef diving and snorkelling, and the highlight is the Marine Park around Moses Rock. But it's a small coastline to absorb a lot of floundering bodies; it's good for learning, but experienced divers will probably only want a couple of days diving here as part of a broader tour of Israel. For a longer dive holiday, skip over the nearby border to Aqaba in Jordan or Taba in Egypt.

Japan

Japan is a country made up of a large number of islands spread over a large range of latitudes, so that dive sites range from cold temperate in the far north to tropical in the far south. Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka prefecture Honshu is a popular destination for mainland Japan diving. The East Coast of Atami is most popular with dive operators for its accessibility and infrastructure, while the West Coast's sites are largely unspoiled, protected from weekend crowds by remoteness and lack of train stations. The southern islands of Okinawa have great diving, but prices are steep: you can expect to pay upwards of US$100 for two dives. Other diving destinations include the Miyako Islands, the Yaeyama Islands and Yonaguni-Jima, the westernmost point of Japan.

Jordan

Jordan is almost landlocked, but has a 15 km coastline along the Gulf of Aqaba at the tip of the Red Sea; see Aqaba for transport and other practicalities. The area around the city is industrial and under port restrictions, but then the diving stretches south from the disused power station all the way down to "machine-gun reef" on the border with Saudi Arabia. These uninviting names are all excellent healthy reefs, normally done as shore-dives as they're so close in. There are several wrecks, best known being Cedar Pride, and in 2017 a Hercules C-130 was sunk nearby. Jordan is friendly and very accessible for westerners and prices are moderate, yet it gets far fewer divers and other visitors than Egypt.

Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia, on the Malay peninsula and northern Borneo. There are over 300 diving sites around Malaysia scattered across many of the islands on the east coast of the peninsula and Sabah.

Maldives

The Maldives are an archipelago in the Indian Ocean south-southwest of India and are considered part of South Asia. The territory of the Maldives comprises mainly water, with only 1% of the country being land-based. The land is spread over 1,192 islets, each of which forms part of an atoll. In total, there are 26 atolls in the Maldives.

Deep in the middle of the Indian Ocean, the entire country is formed by coral reefs and has some of the best diving on the planet. Prices for accommodation and diving services are expensive, though, and currents can be strong on the outer reefs.

Most holiday resorts in the Maldives have a scuba diving facility and there are a number of liveaboard operators offering scuba diving cruise holidays that take guests to many dive sites all over the Maldives. Whale sharks, manta rays, eagle rays, reef sharks, hammerhead sharks and moray eels, as well as many smaller fish and coral species can be seen.

Oman

The Sultanate of Oman is on the eastern side of the Arabian Peninsula, on the coast of the Gulf of Oman. Diving destinations include Muscat, Daymaniyat, Fahl Island and Salalah which has an unusual combination of cold and warm sea life.

Philippines

With 7107 islands, 18,000 kilometres of shoreline and 27,000 km<sup>2</sup> of coral reefs, the Philippines lies in the coral triangle which is one of the most bio-diverse marine regions on Earth. These seas have a Tropical Indo-Pacific ecology, being home to over 450 species of hard corals and more than 500 fish families, which include 2000-2500 fish species. There is a wide variety of dive site types, including reefs, wrecks and underwater caves. Philippines has heavy rain, with frequent typhoons, from July to October: sheltered dive sites may remain accessible, but landside travel becomes impractical.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is notoriously difficult to visit, but very well-preserved, and now open to tourists who can book well in advance. Sites include the Farasan Islands, and around Jeddah and Yanbu.

Thailand

Thailand has beautiful scenery, mostly clear water and Indo-Pacific reef ecology, combined with a tourist-orientated recreational diving industry. There are two diving regions, the Andaman Sea on the west coast (e.g. Phuket) and the Gulf of Thailand on the east (e.g. Pattaya). Both are suitable for all grades, from beginners through to experienced divers. It's diveable year-round, though October to June are best. The visibility close to shore can be grungy, but a mile or so out is up to 30 m. There are vistas of coral gardens, undersea rock formations, hard and soft coral, whale sharks, silver tip sharks, manta rays and even sunken battleships.

Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste or East Timor is geographically part of the Indonesian archipelago, becoming independent after a bitter struggle in 2002. It has a tropical climate with a wet season from October to March and a dry season from April to September. Diving is best between March and December. With the 3000 m deep Wetar Strait just off the north coast, a fantastic array of coral and sea life can be found, most of it straight off the shore. This is a world class dive spot that few know about. It is also a whale hot spot.

Turkey

Turkey is mostly in Asia, but its diving is along an Aegean/Med resort strip that has more in common with Europe, so see that section.

Vietnam

Vietnam in Southeast Asia has a long coastline with many protected bays and islands, such as Hon Mun Island Marine Park, accessed from Nha Trang. Diving is suitable for all grades, from beginners to experienced. There are many varieties of tropical fish, occasional turtles, nudibranchs & other reef invertebrates, and over 400 species of hard coral.

Europe

Diving in Europe usually means the Mediterranean. This is very well-developed for tourism - in fact, overdeveloped, with ugly breezeblock resorts and waters stripped of their coral, fish and artefacts. "The Med is dead" is the woeful refrain. And it's not exactly warm: it's fine for recreational wetsuit diving in summer but deep or extended diving will be better in a drysuit. (There's often a sharp thermocline - that's Latin for "wake-up call" - around the 50 foot mark.) In winter it's cold and often rough, the resorts are as lifeless as the seas, and dive operators may close out of season. And at any time of year the Med suffers by comparison with the Red Sea, where for the sake of an extra two hours in flight, visitors from northern countries can reach better climate and better marine life and probably pay less altogether.

Where the Med scores is in its marine parks. These, where properly protected, have quickly re-established their marine life, showing what is possible on a wider scale. And even in the unprotected areas, there will usually be some crevice or cavern beyond the range of fishing or coral-collectors, and you get a glimpse of the bygone Med that entranced pioneers such as Jacques Cousteau and Hans Hass. The Med is generally good for beginners - it's not tidal so currents are mild - and there are technical training areas, and lots and lots of wrecks as it's so often been a cockpit of war. It also has good underwater scenery in the karstic East Med, with limestone arches, caverns, swim-throughs and chimneys. The biggest selling point is the landside attractions of all the Med countries, so that sights as various as the Acropolis, the piazzas of Florence, the ever-erupting Stromboli and the wacky architecture of Gaudi are all within a short travelling distance from a beach & diving resort, making for a memorable all-round holiday. Diveable countries of the Med include:

Cyprus: Both Greek-speaking Cyprus and Turkish-speaking Northern Cyprus have resort diving, such as the wreck of the Zenobia off Larnaca.

Croatia is becoming better-developed for tourist divers.

France: The best of it is in the marine park in southern Corsica, which is shared with Sardinia in Italy.

Italy: Sardinia has a marine park at its north tip, shared with Corsica across the straits in France. There's also a cave system in Alghero, with crystal clear water and astonishing limestone cliffs. Sicily, and especially the volcanic islands around Lipari, have weird terrain above and below water.

Greece is traditionally hostile to diving. It's right to protect the underwater heritage, but their restrictions have only succeeded in stifling a responsible tourist diving trade, while failing to prevent plunder. They're gradually relaxing, but expect to be closely supervised.

Malta

Malta and its sister island of Gozo have a mix of boat and shore diving to their limestone formations, steep dropoffs, and wrecks. Water temperature varies between 15°C (59°F) in summer and 26°C (79°F) in winter, and visibility is generally good, but autumn / winter are prone to storms.

Spain has marine parks, e.g. Islas Medes near Estartit in Girona. But the best diving is off the Canaries in the Atlantic, see below.

Most of Turkey is in Asia, with only a small part in Europe. So too is its diving infrastructure, all along the Aegean / Med resort strip between Kusadasi and Alanya. But in character it resembles the other East Med countries.

Europe also surrounds the Black Sea, bordered by Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia and Georgia. It's little explored, and is revealing interesting wrecks, but it's no fun for recreational diving. Same goes for the Caspian Sea, which has industrial diving to service the oil & gas rigs.

Europe has lots of dive areas in the Atlantic Ocean and its associated seas. Considering these from south (the most popular) to north (the most challenging):

The Canary Islands are part of Spain but set in the North Atlantic off Morocco. They have year-round diving, with Tenerife and Lanzarote being the best developed.

The island of Madeira is part of Portugal. Stunning rock formations, steep dropoffs and excellent visibility make Ponta de Sao Lourenco one of the best dive areas of Madeira. The island's sites include Arco da Badajeira, Farol, Piquinho, Parede do Sardinha, SS Forerunner and Baixa do Lobo. Sesimbra also has a lot of dive centers and sites to choose from. The other islands of the Azores have been slow to develop tourism.

Belgium has a cold muddy coastline on the North Sea. The main attractions for divers are indoor pools. Nemo 33 in Brussels is one of the deepest indoor swimming pools in the world. Its maximum depth is 34.5 m (113 ft) and the temperature is a constant 30 °C (86 °F). In the indoor dive center TODI in Beringen in Limburg province divers join schools of tropical fish for a swim in a former coal processing tank. The maximum depth is 10 m and temperature 23 °C.

Ireland has a rugged south and west coast, where saw-toothed rocks await unwary vessels.

United Kingdom

This is cold and often challenging, usually requiring a drysuit. There are interesting wrecks and marine environments all around the UK's convoluted coastline and many small islands. The only area for which a diver would make a special trip to the UK is Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, where the German Imperial Fleet was scuttled in 1919.

Iceland: The classic dive in Iceland is in the rift at Silfra in Þingvellir National Park, in fresh water that's as clear as it can get.

Iceland: The classic dive in Iceland is in the rift at Silfra in Þingvellir National Park, in fresh water that's as clear as it can get.

Finally, Europe has the cold, brackish Baltic Sea, of which a good example is Sweden.

Diving in Sweden requires a dry suit at all times of the year. The waters are mostly dark with limited visibility. These conditions have preserved century-old wooden ships, which in warmer waters would have been eroded by marine life. So imagine, if it's too cold and dark for marine life, how much fun it is for humans.

North America

These countries, roughly from coldest to warmest, are Canada, the USA (including Hawaii), Central America (including Mexico), and the Caribbean island nations.

Canada

Canada's waters are dry-suit territory, between cold-temperate and polar; they often freeze in winter yet reach a balmy 21°C in the Thousand Islands region in late summer. Wrecks and rocky reefs are abundant. It is possible to dive with belugas in Hudson Bay, Manitoba, and on well-preserved wooden wrecks in the Great Lakes.

United States of America

The US is a huge country, and diving destinations range from polar to tropical, inland to oceanic islands, and high altitude lakes to caves near sea level.

Diving destinations include:

- California, with a cool Pacific coast, is well-developed for diving. The giant kelp forests are like sunken cathedrals.

- Florida, the south tip of the east coast, has a long coastline with reefs and islets; the interior is limestone so there are flooded caverns and caves. Tourism and transport are so well-developed that it's easy to reach from Europe as well as the rest of the US.

- Hawaii is a group of volcanic islands in the central north Pacific. The main resorts all have dive operations and good sites.

- Lake Michigan is cold fresh water, with some of the best preserved shipwrecks in the world.

- The Thousand Island area spans between New York state and Ontario, with boat operations from both.

- North Carolina is sometimes called the "Graveyard of the Atlantic" because of its numerous shipwrecks.

- Washington's Puget Sound is a rich habitat for marine life.

Central America

Best developed is Mexico, with good diving on both its Pacific and Caribbean coasts, and extensive cave systems.

Baja California, The western peninsula, borders the U.S. state of California. Cabo San Lucas — on the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula is a meeting point of reef and blue water fish. San Pedro Nolasco Island, a small and rugged island in the Gulf of California, is protected as a nature reserve and its coastal waters are well known as a sport fishing and diving site.

Northern Mexico includes the expansive deserts and mountains of the border states; mostly ignored by tourists, this is "Unknown Mexico" and has a thermal water filled sinkhole belonging to the Zacatón system, which is the deepest known water-filled sinkhole in the world with a total underwater depth of 319 metres (1,047 ft).

The Pacific Coast has tropical beaches on the southern coast, and Socorro Island, a small volcanic island in the Revillagigedo Islands, some 600 km offshore, which is a popular scuba diving destination known for underwater encounters with dolphins, sharks, manta rays and other pelagic animals. Since there is no public airport on the island, divers visit here on live-aboard dive vessels. The most popular months are between November and May when the weather and seas are calmer.

The Yucatán Peninsula has jungle, cenotes and impressive Mayan archaeological sites along with the Caribbean coast. Cozumel has excellent and very accessible diving making it one of the most popular diving destinations in the northern hemisphere. The area is well known for reef, wall and drift diving and a lively top-side scene. The region includes the Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park. Cancún and Playa del Carmen in Quintana Roo are known for cavern and cave diving and advanced technical diving in the labyrinth of fresh water cenotes. Banco Chinchorro is an atoll reef in the Caribbean Sea off the southeast coast of Quintana Roo, near Belize. There are at least nine shipwrecks on the reef, including two Spanish Galleons.

Belize has diving similar to Mexico's Quintana Roo.

Its barrier reef is a part of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, 300 m (980 ft) offshore in the north and 40 km (25 mi) in the south of the country. Much of the reef is under legal protection yet where responsible diving is allowed: a World Heritage Site with seven marine reserves, 450 cays, and three atolls.

Honduras has good diving along its Caribbean north coast.

The best developed is Roatán, which is one of the Bay Islands some 40 km north of the mainland. There are also dive sites on the other Bay Islands of Guanaja, Utila and the Hog Islands (Cayos Cochinos). They all enjoy year-round warm climate and sea, underwater viz of 60 to 100 ft, and it's usually calm. This makes them a good choice for learning to dive. For advanced divers they boast amazing reef formations such as canyons and swim throughs galore. The deep waters minutes away from shore lend themselves for Tec Dive training and exploration.

Caribbean

Antigua: Dive sites include Darkwood Reef & Charlotte Reef.

Many of the dive shops in Aruba will pick divers up at their hotel and bring them to the dock or dive shop, and drop them off at the dive shop when their dive is over.

Barbados has mellow reef and wreck diving along its sheltered southwest and western coasts. It's a good place for learning and for novice and intermediate divers; there's nothing ultra-deep or highly technical. Most dive shacks are in Bridgetown, but they pick up from the hotels along the two coastal resort strips, and from the cruise terminal.

The name Bahamas means "shallow seas" and it comprises an extensive submerged limestone platform, with high points here and there just breaking the water to form an archipelago. The Bahamas are warm year-round, basking in the Gulf Stream, and hurricanes seldom strike. All the inhabited islands have local diving, and some have extensive inland cave systems. New Providence is the least interesting, being dominated by the sprawling capital Nassau, but is the base for liveaboard cruises around the archipelago.

Bequia's dive sites include Devils Table, North West Point and Boulders.

Bonaire lies 80 km north of Venezuela. It's low-lying and arid, with haunting landscapes of salt pans, old slave huts, pink flamingos and wild donkeys. It has shore-diving all along its sheltered west coast, which is the hotel strip - most have a "house reef", and many have jettys so you can step straight onto a boat. Dive boats often visit the reef along the west side of Klein Bonaire, the small desert island just off the main town Kralendijk. The exposed east coast is seldom dived. Bonaire is a good destination for beginners and mellow intermediate divers, it's not techy. The climate is warm and breezy all year round.

The BVI comprise some 60 islands and islets, mostly within a few miles of each other. The islands are in relatively shallow water, so most dive sites are shallower than 100 feet (30 m). The diving is predominantly based on wrecks and tropical coral reefs. There are 70 dive sites marked by mooring buoys, and several unmarked.

The three islands are Grand Cayman, Little Cayman and Caymaan Brac. They're the tips of an underwater mountain, which has near-vertical sides in places, sometimes close to shore. In addition to the coral reefs, with their typical Caribbean fish, and invertebrates, the wall diving is an unusual experience for most scuba divers. Scuba diving in the Caymans can be done from a boat, or at some dive sites, from a shore entry. Visibility is good due to the island's geography. There is very little runoff of silt or fertilizers from the land, and the steep walls result in the reefs being unusually close to deep ocean water.

Cuba's dive destinations include Maria la Gorda.

Dominica's terrain is as spectacular underwater as it is above.

Martinique's former capital Saint-Pierre has a harbour littered with wrecks, sunk by the 1902 volcanic eruption.

Saba is a small volcanic island of the Netherlands Antilles, with steep drop-offs and submerged pinnacles that are virtually untouched.

Saint-Barthélemy's dive sites include Ile Fouche, Ile Chevreau, La Baleine and Sugarloaf.

St Kitts & Nevis: Saint Christopher, better known as St Kitts, has dive sites including Palmer’s Paradise (Turtle Canyons), Old Road Town Bay, Sandy Point Bay, Mystery Shoal and Popeye’s Corner.

Nevis is the smaller of the two islands; it's little developed, a quiet and relaxing place. Its best-known dive site is Monkey Shoals.

Saint Lucia's sharp volcanic peaks continue underwater, with the best of the scenery in the south, e.g. at Anse Chastanet near the town of Soufrière. The plunging drop-off makes many of the reefs accessible by shore-diving or a very short boat ride.

Saint Martin dive sites include Hen and Chicks, Moon Hole, Cable Reef, Groupers, The Maze, Alleys, Proselyte Reef, and HMS Proselyte Wreck.

Trinidad has muddy waters from the outflow of the Orinocco. Its smaller island of Tobago is clear of this, is well-developed for diving and other tourism, and has direct flights from North America and Europe.

Oceania

(Note: Hawaii is listed under United States of America in North America)

Australia

The coastline of Australia is very long and includes a considerable range of water temperatures and marine ecologies. The most famous region is the Great Barrier Reef off Queensland, but there's plenty more. There is temperate water diving along the south coast and off Tasmania.

Chuuk

Chuuk lagoon is renowned for the huge number of ship and aircraft wrecks from World War II's Operation Hailstorm. Chuuk Lagoon is part of the larger Caroline Islands group. During World War II, Truk Lagoon, as it was then known, was the Empire of Japan's main base in the South Pacific theatre. A significant portion of the Japanese fleet was based there. Operation Hailstone was launched from the Marshall Islands, and the attack on Truk lagoon started in the early morning of February 17, 1944, and culminated in one of the most important naval airstrikes of the war. 12 Japanese warships, 32 merchant ships and 249 aircraft were destroyed making the lagoon the biggest graveyard of ships in the world.

Fiji

Fiji is a Melanesian country in the South Pacific Ocean which includes 322 islands, of which 110 are inhabited, and 522 smaller islets. The capital is Suva on Viti Levu. The Fijian islands have a year-round warm tropical climate. Water temperature ranges between 23-30°C (73-86°F). Visibility ranges between 25-50 m (80-165 ft). A network of coral reefs surrounds all the islands and atolls. Fiji is a good place to discover the scuba diving world. There are around 1000 species of fish and several hundreds types of coral and sponges at a wide variety of dive sites for divers of all levels.

Guam

Guam has some of the best dive sites in the world since there has been minimal tourist impact compared to other better known dive locations. Piti Bomb Holes has been built up as a tourist attraction allowing tourists to descend into an observatory where they can take in the beauty that has grown in a sinkhole. (The name "Bomb Holes" is a misnomer.) Divers may dive around this attraction and feed shoals of fish for the amusement of the tourists inside the subaquatic observatory as much as for the divers' own amusement.

While many of the dive sites can be reached by land, some of these entry points require a long walk over coral or a long surface swim. Also, because so much of the island is controlled by U.S. military bases, many of the dive sites are accessed by land through the military bases.

Niue

Niue has extremely clear water. It is a great scuba diving and snorkelling destination.

New Zealand

New Zealand is a island country in the temperate South Pacific, with an extremely long coastline for its size, and a remarkable number of coastal islands. Much of this coastline is diveable, and some of the sites are really spectacular.

New Zealand has a mild and temperate maritime climate with mean annual temperatures ranging from 10°C (50°F) in the south to 16°C (61°F) in the north. The weather is notoriously variable. The expression "four seasons in one day" sums it up quite well. It is positioned across the division between subantarctic and subtropical water masses, and this provides a large range of conditions and habitats which support a wide diversity of marine life.

Palau

Palau has a shark sanctuary and is a known destination for shark-watchers. Its most famous site, the jellyfish lake, doesn't permit divers, you just snorkel among them.

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea comprises the eastern part of the world's largest and highest tropical island, New Guinea, together with many smaller offshore islands. Though its coastline is not exactly smooth due to its mountainous geography, Madang is a town with fine scuba diving.

Saipan

Saipan in the Northern Marianas is a popular diving destination in the Pacific. It is a typical middle-aged island composed of ancient fossil-rich coral limestone atop a subsiding, extinct marine volcano. A fringing reef of healthy offshore corals forms an extremely large lagoon and many small shallow lagoons in its larger bays, and a few offshore subsurface coral mounts. Saipan has excellent reefs, white beaches, underwater caves, WWII shipwrecks, underwater munitions dumps, and underwater airplane wrecks which provide diving that will appeal to most divers. Visibility, typically in the 5090 ft(1630m) range, varies enormously based on location, tide, and season. Waves seldom exceed 12 ft(3060 cm) in height, except during typhoons and tropical storms.

Vanuatu

Vanuatu is an archipelago nation in the southwest Pacific Ocean, north of New Zealand and east of Australia. It has intermediate level wreck diving, including penetration, on the President Coolidge, and blue hole diving with excellent visibility.

South America

Brazil

Brazil has a long coastline, mainly on the South Atlantic, and mostly in the tropics, with a few offshore islands. There are also liveaboards in the Northeastern region. To dive in public parks (like Fernando de Noronha) one must be certified by one of the agencies recognized by IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro de Administração do Meio Ambiente), a federal organ.

Colombia

Colombia has some of the cheapest diving in South America. A cheap place to learn is Taganga. The islands of Isla Gorgona, San Andrés and Providencia have some really good diving. A little known but excellent location for hammerhead sharks, whale sharks and other large pelagic beasts is Malpelo Island, accessible only by liveaboard.

Chile

Chile is some 4000 km long from north to south, so its sea conditions are as varied as its land climate. It's relatively undiscovered and undeveloped for diving. The north is obviously warmer, with sites and dive operations around Antofagasta, La Serena, and resorts in the Santiago area - you need a chunky wetsuit by these latitudes. and drysuits south of here. Chile's best known diving is on Easter Island, 3500 km out in the Pacific. A mere 700 km out, the Juan Fernandez Archipelago is also good.

Ecuador

Ecuador rules the remarkable Galapagos Islands, with schools of dozens of hammerhead sharks, while whale sharks and other large sea creatures are also frequently sighted.

Get in

Destination and region "Get in" sections describe the usual options for getting yourself someplace. But some aspects are specific to diving, so this section outlines those, from the time you commit to a destination to the moment you're poised at the water's edge ready to plunge in. In summary these are to stay healthy and current, check your insurance, decide what kit to take, check in with the dive centre at the destination, then travel with them to the specific dive site. The subsequent "Get around" section describes what happens next.

Stay healthy and current

Standard advice on healthy active lifestyles applies to diving as to everything else. You want all-round cross-fitness, stamina and suppleness; there's nothing specific for diving. A steady routine is worth more than a spasm of activity. "Staying current" means not letting your skills decay since your last dive. Resort centres are generally okay if you've dived within the last six months, though this does not necessarily mean you have not lost your edge. They become less happy the longer your gap, the lower your previous experience, and the more challenging the intended dive. Consider how you might schedule interim dives, but realistically, a time-poor traveller might only manage a single diving vacation per year. What the centre might do is assign you to a "check-out dive", i.e. tagged on to the beginners' class. Once the instructor reports back that you looked okay, you'll be restored to the main boat.

Check your insurance

Is it in date, does it cover the destination you're heading for, and include scuba diving? In the Med, is the policy restricted to Europe, or include Anatolian Turkey or Tunisia, and what about Cyprus (part EU, part not)? An annual multi-trip policy is often the best deal and often includes diving without extra charge, within recreational limits and your level of qualification - typically to 30 m / 100 foot max depth. That demonstrates that insurers know that diving is safe, compared say to winter sports for which you'd pay extra. But when it goes wrong, it can go horribly wrong, perhaps in a resource-poor country that simply can't afford to launch a search and rescue operation unless they know who's paying. Then come the medical bills, the onward emergency transfer to a decompression pod, the specialist treatment and rehab before you're stable enough to be repatriated. US$1,000,000 is the minimum cover needed against calamities on this scale. There are organisations that specialise in insurance for divers and diving travel, including loss of equipment, expert medical advice, treatment and emergency transport.

What to take on the trip?

The one absolute essential (beyond your passport and payment cards) is your dive certification and log book, and the lesser your certification, the more important the log book will be. Without these, any reputable diver operator will be forced to regard you as an untrained beginner, and the most they'd allow is a "try-dive" under instructor supervision. If these vital documents go missing in transit, it may be possible for your training agency to fax or email evidence of your qualification. But this is slow, uncertain and may be pricey so if you have them online, email them to yourself just ahead of the trip.

Always take your own mask, fins, and dive computer if you have one, as they're lightweight, along with standard beach items such as towel, swimwear and tote bag.

As to the rest, it's a trade-off between weight, bulk, assurance of knowing your own kit, and quality and cost of rental. (It's not really a choice of buying versus rental, as you may well own one or more sets of kit but opt not to take it.) For a warm water trip, a wetsuit plus regulator and BCD will fit a standard airline 23-kg bag and leave just about enough room to crush in lightweight clothing for a week's vacation. When were those items last serviced, do you need to sort this before the trip? Try to use a recently serviced regulator before going away with it in case the settings are not to your liking. It's hardly worth lugging full kit for less than 3 days diving. A small camera can go in your hand luggage but an elaborate camera will mean a second checked bag to accommodate all the lighting, mountings and housings, plus security against thieving hands. For a cold water trip, you do need to take your own drysuit plus associated warmwear, and this alone will fill most of one bag. Bearing in mind that you also need thicker, rainproof clothing for such a climate, reckon on a second bag.

You can't fly with weights or tanks, which are readily available at dive centres. If they're not, then the trip becomes an expedition, with a truck to carry the heavy kit overland, probably also with an air compressor for refills, loads of tools and spare parts, and towing your own boat. Something on this scale needs organising by an experienced expedition leader, who will appreciate your offer to take on delegated tasks. You also can't generally fly with rebreathers.

Check in with the dive centre

Worth checking ahead, especially in a one-centre resort: one risk is they're booked out, but more likely they may have folded, or just gone dormant if business is slack.

On arrival (and they may pick up from hotels), there's paperwork to do. They need to see your certification, log book, and payment card. On insurance they may simply ask you to sign that you've got some, or demand to see the small print about the coverage.

The agency that you trained with may not be one to which the centre is affiliated. It's not a problem so long as you qualified from that training, and that the agency was one recognised worldwide. There are look-up tables that show what any particular qualification would equate to in another agency. As of 2018, the following are recognised:

- ACUC: The American Canadian Underwater Certifications.

- ANDI: American Nitrox Divers International.

- BSAC: The British Sub Aqua Club, bases its training on a network of affiliated clubs.

- CMAS: The Italian-based Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques, an amateur non-for-profit international organization that takes a more comprehensive approach than many of the commercial agencies. Training and certification is available from either national diving federations affiliated to CMAS or from specially-accredited dive centres known as CMAS Dive Centers (CDC). Certification from national diving federations and CDCs is considered to be equivalent, however training may vary from CMAS standards due to requirements mandated by a national federation. Most the larger national federations are in Europe (particularly FFESSM in France and FEDAS in Spain), and their qualification cards will sometimes have CMAS qualification on one side, and the national federation on the other. Provided it has a clear CMAS endorsement, even cards from minor national federations will be recognised worldwide. Note that BSAC (see above) does not issue CMAS cards by default, but can issue one equivalent to your highest BSAC qualification for a small fee (about 25 UK pounds). If you are a BSAC trained and diving in France (including French overseas regions like French Polynesia) you may find this worthwhile, as it can save a lot of hassle due to highly regulated nature of French diving.

- GUE: Global Underwater Explorers, concentrates on technical and cave diving specialities.

- IANTD: International Association of Nitrox Technical Divers.

- IDEA: The International Diving Educators Association.

- ISI (dead link: June 2020): The Independent Scuba Instructors.

- NAUI: The National Association of Underwater Instructors, US-based, is the oldest recreational scuba certification agency.

- PADI: The Professional Association of Diving Instructors, the largest scuba certification agency, a commercial agency targeted towards recreational divers who want to learn quickly.

- PDIC: The Professional Diving Instructors Corporation.

- SDI/TDI: The Scuba Divers International/Technical Divers International, a certification agency designed to train with an emphasis on practical diving skills. SDI focuses on the recreational side of scuba diving and TDI is the mother branch that specializes in Technical Diving.

- SSI: Scuba Schools International, another large commercial agency.

Reaching the dive site

There are three main ways of travelling to the dive site: day-boats, shore dives, and liveaboards where the boat itself is your accommodation.

Day-boats

The majority of tourist, qualified but non-technical diving is from day-boats, as the sites of interest are usually a few miles from the dive centre, and too far from shore to swim to. Day trips typically head out in the morning, when the sea is quieter, for a "two-tank dive", i.e. two dives with a surface interval between. With short travel times they return to base in that interval, with longer times they make a day of it at sea.

Boats vary greatly in size and facilities, so the newly-arrived visitor should ask about this, to understand what to bring and what not to bring. The most spartan are small boats or RIBs (rigid inflatable boats) with outboard motors. You will already be in your wet- or drysuit on boarding, with kit assembled. Everything is liable to get drenched and there's no space for more than a small tote-bag for sunhat and glasses. Boats for longer trips are progressively roomier, with a wet deck where the kit stays and divers assemble, toilets and showers, and indoor and sun-deck dry areas. They may offer a catered lunch, snacks, and help yourself to coffee. They may carry several parties of experienced divers, trainees, snorkellers and non-diving sunbathers. Note that it's travel time not distance that governs the type of boat: a RIB can go blazing out to reach sites within the hour that a conventional boat would need much of the day to reach and return.

If you suffer travel sickness in cars then best assume you'll feel sick on the boat and take medication, since it generally has to be taken an hour before sailing. Nausea can be reduced by standing up out on deck and fixing on the horizon, and by being midships around the centre of pitch and roll. It will subside underwater as you drop below the wave action and the pressure reduces your gut volume. It will return inexorably as you ascend, bob about in the waves, and try to de-kit in a lurching boat. How to vomit underwater is just another of those skills you'll acquire; fish will surround you to admire your technique and devour its results.

There will be two briefings, listen carefully to both. Once everyone's aboard you get a "boat briefing": wet and dry areas, rules about shoes, firm grip on the stair rails, and never put anything into the toilet that you haven't eaten yourself. The second, approaching the site, is the "site briefing:" underwater topography, things you might see, and intended dive route, depth and duration. You especially need to know the method for exiting the boat, and for getting back aboard.

Even larger boats - liveaboards - are considered below. Some centres use public ferries to reach their sites, connecting with a small boat or shore operation there. Cruise liners often include diving in their excursions, but in effect it's as if an entire resort has become mobile to rendezvous with a dive centre. You dock or transfer by small boat to the centre and carry out the dive just like a land-based visitor.

Shore dives

Shore dives are where you swim out from shore, or dive immediately, onto a nearby site. It's cheaper, avoiding all the business of boats, but it's not necessarily easier. There may be only limited spots where you can get into the water, across slippy rocks or sharp coral, amidst breaking waves. Coming back, those spots may be difficult to locate from the water, or be inaccessible because the tide has dropped and they are now too high. You may be more restricted on timing: the hour after high tide has the minimum current. Even a swim of 90 m (100 yards) can be difficult, and it's worse coming back - and suppose there was a problem and you were trying to tow your buddy? Would there be a shore watcher looking out for you, and how readily could they assist you, lacking a boat themselves?

Shore diving is the main style in some resorts, e.g. Aqaba in Jordan, and at inland sites such as lakes and flooded quarries. It's probably at such sites that you'll first find yourself diving truly independently, with a buddy of equally limited experience, and no divemaster supervision. This is where you learn skills around risk assessment, dive planning and logistics, and start to feel the responsibilities that others have till now shouldered for you.

Liveaboards

Liveaboards are boats with their own sleeping accommodation plus catering. Trips range from a single overnight to a fortnight or more, with 3 to 5 dives per day. At the budget end, accommodation is basic, with 4 people sharing cabins and several cabins sharing shower and toilets. The net cost per dive will be lower, but multiplied by many more dives, so "budget" won't mean cheap. Top end accommodation resembles, and costs like, a luxury cruise. But even on the best boats, there is little escape from engine noise, fellow divers, or the restless sea. It's all about the diving, waking early for the first briefing and completing the last dive at sunset, day after day. Non-diving companions are going to need a really absorbing blockbuster paperback. Although training courses are conducted from liveaboards, the point of them is to reach outlying sites beyond the range of day-boats, where there may be excellent diving but more challenging conditions. Beginners need to concentrate on basic technique and had best defer the liveaboard experience until they've had a few day-boat trips and feel comfortable at sea.

When travelling on a liveaboard:

- bring as little as possible: a few changes of weather-appropriate clothes, sleep gear, toiletries, light-weight entertainment (especially non-electronic) and your dive kit;

- space is always at a premium, and it's easy to get things mixed up and annoy fellow divers, keep your dive gear together in a tub or bag on the deck;

- label your possessions with your name, as they will be mixed up with a lot of similar looking equipment;

- observe the boat's wet / dry protocols, drying off before going inside;

- most boats have a limited supply of fresh water for drinking and washing: have short showers.

- make sure you know the emergency exit routes.

Get around

Humans have been sploshing around in water for hundreds of thousands of years yet biologically we remain badly adapted to anything beyond a quick dip. All the diving equipment and techniques that we utilise are designed to overcome our serious natural shortcomings, compared to other air-breathing animals that thrive underwater. This page is emphatically not a dive training manual but a travel guide, so the present section considers the very short trip that we take from leaving the surface down to the sea bed, and return. It considers the multiple problems we face and introduces the kit that overcomes each of them. Subsequent sections describe what we might see or do down there.

-

We can barely swim, especially when wearing all the essential scuba gear. We compensate first by using a boat (or, for shore-diving, a motor vehicle) to get close to the dive site. Then we avoid fighting rough seas or strong currents: the "slack" hour or two after high tide is usually the quietest. Or we may deliberately drift with the current, while the boat follows the dive leader's surface marker buoy. And third we wear fins, and move them in a measured, efficient way to propel ourselves. Fins may be open-heel (with a rear strap, worn with boots) or full-foot (one piece over bare feet coming up to the ankles). Open-heel are more adaptable, since the strap adjusts, and they're usually worn over boots, very useful for shore diving or in colder water. But they chafe bare feet; full-foot fins are more comfortable here, are more efficient for movement, and a good choice when diving from a boat or jetty in warm water.

-

We can't see underwater because we lose the refractive change between air and eye, so focus is impossible. So we wear a mask which creates an air space before the eyes. It also covers the nose (unlike the goggles of swimmers) so we can nasally exhale to equalise the internal pressure and drive out any water that seeps in. The mask can also be fitted with corrective lenses. This restores clear (albeit slightly magnified) vision. But the water becomes dark and gloomy at depth, and the colour is progressively filtered out, so we might use a torch, plus flash or video light for photography. Other lights (eg strobes and glowsticks) are more to be seen by (ie by other divers, or by the boat on surfacing) than to see by.

-

A snorkel is a short curved tube with a mouth grip, so we can breathe at the surface with our face underwater. It may be strapped to the mask or slipped under the strap and is mostly there to solve the "barely swim" problem, by conserving air in the tank while we swim on the surface. Once underwater, obviously we can't breathe from it, and it can be a nuisance in cramped environments since it can snag, either causing the mask to flood or dislodging it altogether. So for some dives it's optional.

-

It's cold, and it gets colder. Water is a much better conductor of heat than air, so even in tropical waters, a temperature that would be pleasant in air soon becomes unpleasant, and leads to hypothermia. In deeper waters or at high latitudes it's unpleasantly cold from the start, and naked survival time might be measured in minutes. Even plump humans have nothing like the intrinsic protection of seals. We therefore put on warmwear, the simplest being the wetsuit for warm water. As the name implies, it floods, but provides an insulating layer of foam neoprene or similar material, and the trapped water warms up using your body heat. (It's ineffective if loose, as the warmed water is continually flushed by cold water whenever you move.) Thickness ranges from 0.5 to 7 mm, and may be a one- or two-piece whole-body design, or a shortie covering down to mid-thigh. 3-5 mm is about right for the tropics, 7 mm is better for temperate waters. Wear your usual swimwear under the suit, and you could add a T-shirt if a rental suit feels loose. The suit also protects against stinging creatures in the water, chafes and scrapes getting in and out, and sunburn on the surface. The thinnest suits are worn primarily for those protections.

-

And colder and colder. The water temperature always lags a month or so behind the climate. On a bright day in early summer it looks lovely, everyone rushes to jump in, but the water is between winter and spring and there's a spate of fatal incidents. With a wetsuit you can manage a dive if it isn't too long, but then you come up with blue lips and get even colder on the surface - not a good preparation for a second dive. Cold waters need a drysuit, which doesn't keep us warm. Rather, we put on warmwear like a quilted under-garment, then the drysuit keeps the warmwear dry. It also protects against stings and chafes, and is supplemented by gloves and hood - these are often themselves wet.

-

We can't breathe underwater. So we dive with a tank or cylinder of air, which to last long enough while being compact must be highly compressed, typically 230 bars when full. Air is delivered through a two-stage regulator: the first stage, clamped to the tank, takes the pressure down from 230 to 10 bars. The second stage, gripped in the mouth, feeds air on demand at ambient pressure, which is one bar at the surface and increases by one bar for every 10 metres depth, as described below. There are also feeds to the buoyancy control jacket, to the secondary mouthpiece to assist another diver, to the tank contents gauge, and where worn to the drysuit. A typical resort dive turns-about at the 150 bar mark, approaches the shallows around 100 bar, and surfaces with 50 bar remaining. Air usage increases inexorably with depth, duration, exertion and body size, but being economical with air consumption is the mark of a good diver.

-

We can't speak intelligibly, even with breathing gear. So there's a vocabulary of hand signals to learn, from the routine to the exotic or ribald.

-

We're either too buoyant or not buoyant enough. All that kit feels a ton as you stagger across the boat deck, but it's bulky, and once supported by water, you can't submerge unless you carry extra weight. But at depth the buoyancy is squeezed out of the suit, equipment and yourself, you sink, you lose even more buoyancy, and so on down. What's needed is neutral buoyancy, floating comfortably and moving neither up nor down. This is achieved in three stages. The first, macro solution is dive weights, several pounds / kilo of lead carried on a belt, harness or pouch. The right amount just balances the buoyancy of the kit, and the divemaster will check the weighting of newcomer divers at the surface, and adjust before descent. He / she may also carry a little extra, to donate underwater to divers who didn't get it right. Weight must be capable of being jettisoned in an emergency so that the stricken diver floats up. Divers may also use small "trim weights" to optimise their balance, eg drysuit divers may use ankle weights to stop their feet floating. The second, meso solution is a buoyancy control device or BCD: a jacket or wing that is inflated from an air feed or deflated. The BCD is how to manage the buoyancy changes as the dive depth varies. (Or mismanage - every beginner will at some point suffer an embarrassing runaway ascent, through adding air at depth and failing to blow it off soon enough on the ascent.) The third, micro solution, which some instructors don't mention, but is universal, is breath control. Never hold your breath underwater, particularly when ascending, but it's fine to modify the depth and rate of the breathing cycle: a hard expiration to help you descend, a little extra breath in to lift clear of the coral you risked snagging.

-

We can't withstand pressure, or live without it. On the surface we live under one atmosphere of pressure, one bar or 1000 millibars. Go down just and we're under 2 bars. Every air-containing space in our bodies, and the air in our BCD, is compressed to half its surface volume. Continue down to , a routine diving depth, and it's 3 bars, one third the volume. And so on; something's gotta give. The most sensitive spot is the eardrum, so we pinch the nose and puff to drive air into the middle ear and equalise; defects or weakness of the eardrums is one common barrier to diving. The solution is in the regulator, which supplies air at ambient pressure. So at the air within us is at 2 bar matching the external pressure and we feel fine, at the price of other problems. One is that we are now consuming the tank contents twice as fast, and at it will be three times as fast. Another is that with rising pressure, more nitrogen dissolves in the blood stream and tissues, and acts as a narcotic - it's the same biological mechanism as nitrous oxide or Entonox. People's susceptibility varies, but a beginner could reckon on being drunk at , dead drunk at , and dead at . Hence the cautious depth limits for diving. On ascent, even after a relatively shallow dive, the accumulated nitrogen must escape, with potentially disastrous consequences if it forms bubbles that block the blood stream. We minimise these by limiting dive depth and duration, by ascending slowly, and by pausing the ascent around the 6 metre (20 ft) mark for a "safety" or decompression stop. Once back on the surface we avoid heavy exertion, wait for perhaps an hour before diving again, plan a shallower second dive, and don't fly or ascend high mountains for 24 hours. The other potential calamity is if in spite of the warnings you did hold your breath while ascending, or had a lung abnormality that obstructed full venting, the air inhaled at depth would remain at much greater pressure than your surrounds. Again, something's gotta give, and bang! it's you.

-

Underwater we lack the normal cues for orientation so we need instruments such as a depth gauge, a compass and a watch or timer. These are often integrated into a dive computer, which tracks depth, time and gas consumption and indicates how soon and how slowly the diver ought to ascend.

-

Other dive accessories include guideline reels, to spool out as you go into a wreck and reel in to find the way back out; a small knife in case you snag on fishing line or nets; a slate to scribble messages to your buddy; a mirror (eg an old CD) and whistle to attract the boat's attention; and a little mesh "goody-bag" for carrying small wet items. General accessories, helpful for any boat-trip, include sun protection (floppy hat, shirt, sunblock, sunglasses), water bottle, flip-flops, and extra layers for the cold evening breeze.

See

.jpg/440px-Bull_shark_(2007).jpg)

- Your buddy and the dive guide - where are they? If you can't see them, find them fast.

- Marine life ranges from the minute to the small fry to the "big-safari" beasts, all equally fascinating. Some are rooted to the spot or occupy a fixed niche (eg sea horses), so the dive guide knows their abode and points them out. Others are territorial and in season will always be found in an area - triggerfish hurl themselves against anything that comes close to their eggs. Bigger beasts range over a greater area so an encounter can't be guaranteed: turtles munch away, sharks snooze beneath overhangs, seals and sea-lions may approach and play with you.

- Reefs are shallow areas amid deeper water: so they have an ecosystem of marine life, they are often the cause of shipwrecks, and they may create a shelter on their leeward side that's much calmer than to windward. Thus many dive sites are on reefs. Rocky reefs, found worldwide, are simply that. Cold seas often have a kelp forest and other seaweeds down to about , or wherever the light gets too dim, then various zones of filter feeders like soft corals, sea squirts and sponges predominating beyond. Coral reefs are found only in clear warm waters (but can't survive hot, so global warming is a serious threat). Here the reef has been built up from the stony skeletons of billions of creatures, with their living descendants forming a riot of colour and structure. The shallow areas tend to have softer and more flexible growth that can withstand wave action. Further down are hard corals, a sculpted Garden of Eden where everything is trying to sting everything else including you, so look but don't touch. Artificial reefs are structures (often obsolete ships) sunk to be an attraction in their own right, and to act as a foundation for colonising marine life. They also include the supports of piers, bridges and marine structures such as oil rigs.