On the trail of Kipling's Kim

On the trail of Kipling's Kim

Kim, by Rudyard Kipling, is a novel set in British India under the Raj toward the end of the 19th century. The story is about coming-of-age, adventure, espionage, travel, and the diversity of India's ethnic groups and characters, and is one of Kipling's best known works.

Kimball O'Hara is a 'poor white' 13-year-old Anglo-Irish orphan happily living on the streets of Lahore, where he is known far and wide as "Little Friend of All the World." He encounters Teshoo Lama, a Tibetan monk in search of a river of healing that will free him from the Buddhist cycle of rebirth. The worldly-wise Kim takes charge of the naive Lama, guarding and guiding him on the road while furthering his own quest for a "Red Bull on a Green Field" – his father's old regimental badge.

Kimball O'Hara is a 'poor white' 13-year-old Anglo-Irish orphan happily living on the streets of Lahore, where he is known far and wide as "Little Friend of All the World." He encounters Teshoo Lama, a Tibetan monk in search of a river of healing that will free him from the Buddhist cycle of rebirth. The worldly-wise Kim takes charge of the naive Lama, guarding and guiding him on the road while furthering his own quest for a "Red Bull on a Green Field" – his father's old regimental badge.

'Captured' by the regiment, Kim is saved from a military orphanage by the lama's decision to pay for the best education available to a Sahib's son in India. At the same time Mahbub Ali, an old Lahore acquaintance, brings Kim's background and talents to the attention of Colonel Creighton of the Ethnological Survey, who is also the head of British military intelligence in the subcontinent. This gets the lad involved in a historic geopolitical competition against the Russian Empire up north – the distance between its frontiers and British India's kept shrinking throughout the 19th century – referred to as the Great Game.

For the next three years, Kim receives a strict British education in term-time – while perfecting skills of another sort during his holidays. Finally released at age 16, he re-joins the Lama to wander across northern India – the one to 'graduate' into his vocation, the other to fulfill his quest.

The modern day traveller who attempts to retrace Kim's path will naturally find that much has changed, while quite a bit hasn't. Some of the train journeys that Kim took are no longer possible, because the routes now cross the international border between India and Pakistan, two countries that are in a state of conflict. The British have left, but many of their institutions endure and the people Kim encountered may dress and speak very differently from his time, but continue to be an interesting lot. Central Asia continues to be an area of conflict, though the disputants have now changed.

Information related to making the journey in the present day is written in bold in the article.

See South Asian wildlife for the flora and fauna of India.

Understand

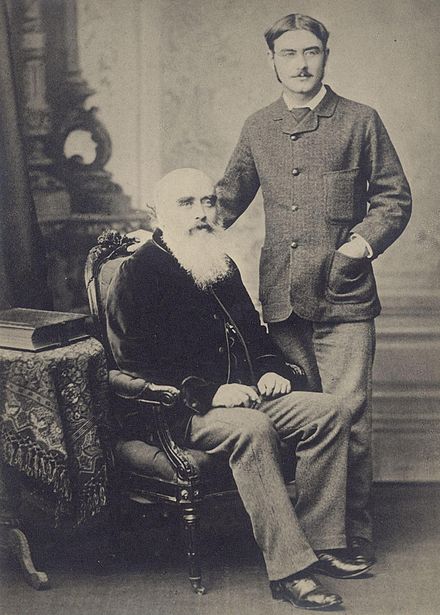

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

Kipling was a short-story writer, poet and novelist. He was born in Bombay where his father, John Lockwood Kipling, taught at the JJ School of art. He was shipped to Britain at the age of 5 to be educated, and returned to India as a teenager. His 5 years in Lahore while Lockwood Kipling was curator of the Lahore museum were formative. He used Lahore as the base to write extensively about India.

There is no doubt of his understanding of India or his love for the Indian character, as displayed in one of his most famous poems, Gunga Din. But Kipling was also an unabashed imperialist who believed in the cultural superiority of British institutions. His problematic and controversial poem The White Man's Burden, encouraging American imperialism in the Philippines, is of a piece with his view that spreading the benefits of modern civilization to the less developed peoples of the world was a solemn duty, a necessary burden even, for the whites. Having said that, it is unlikely that Kipling was a racist in the modern sense – he probably viewed the (to him, undoubted) cultural superiority of the white people a result of historical factors rather than an innate feature of skin colour.

Kipling left behind a rich body of work, including great children's literature like The Jungle Book, poems like If-, probably the most famous depiction of British stoicism, and clearly deserved his Nobel prize for Literature. On the other hand, his act of raising a purse for General Dyer, the perpetrator of the Jallianwala Bag massacre at Amritsar, an atrocity that appalled even that arch-imperialist Churchill, was shameful.

One gets the feeling that to read Kim is to read the story of Kipling's life as he would have liked to live it. Of course, Kim was an orphan while Kipling was not; and Kim entered adolescence speaking fluent Urdu and with barely any English, while Kipling, who moved to Britain at the age of 5, was probably proficient in the Queen's language at Kim's age. Kipling returned to India as a teenager, spent time in Lahore with his father, and clearly loved the place. He may have, through Kim, reconstructed the childhood he would have had if he had never left for Britain.

Kipling's portrayal of both Indian and British characters in the novel is a joy to read. Teshoo Lama's other worldliness and aversion to getting caught in Samsara, and the fatalism and the superstitious character of the average Indian, all reflect his deep understanding of the nation's psyche. The British people that are portrayed positively, like Creighton or Lurgan, are the ones who have immersed themselves in Indian society and can communicate with the natives in their languages, while the ones who can't – like the two clergymen that Kim encounters – are caricatured and made fun of. In particular, Creighton is an ethnologist, much like Kipling's father who was an expert in Buddhism, and indeed Creighton acts as a kind of father figure to the orphan Kim.

The British Raj was much larger than modern India; it included what are now Pakistan and Bangladesh together with most of Burma. Much of the tale revolves around the "Great Game", a phrase the novel made famous although Kipling did not invent it. This was a fierce competition between the British and Russian Empires for influence, particularly in Central Asia but also as far afield as Korea and the Caucasus.

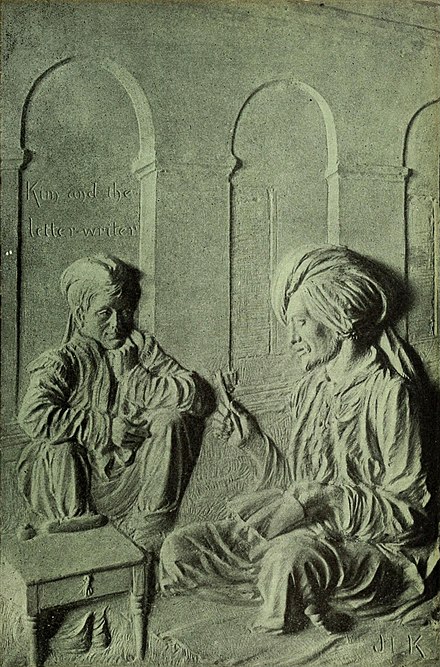

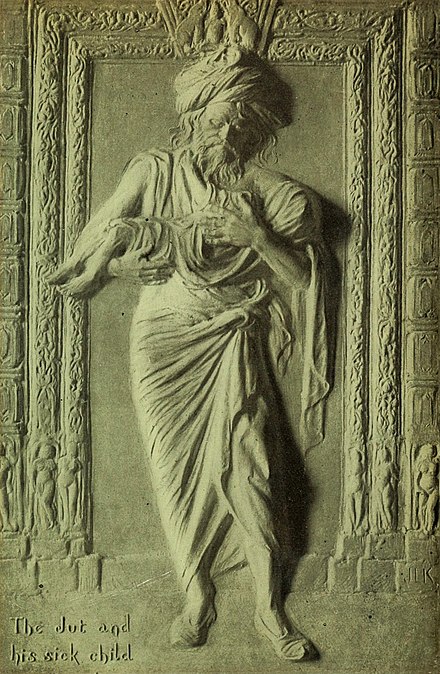

This account is based on the Project Gutenberg text of Kim; they have tens of thousands of free books including the complete works of Kipling and most other 19th century classics. All quotes are from that version and are indicated by italics. The illustrations below and the banner above are by Rudyard Kipling's father, John Lockwood Kipling, from a 1905 edition of Kim; they are now all out of copyright and available on Wikimedia Commons.

Peter Hopkirk is a well-known writer on this period; his The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia is excellent. He has also done Quest for Kim: In Search of Kipling's Great Game which covers the topic of Kim's travels in far more detail than we can attempt here.

Recreating the journey in the present day is made difficult by the strained relations of India and Pakistan; for example the countries have been at the brink of war as late as 2019. There are very few border crossings, and the Samjhauta Express train service between Lahore and Amritsar has been suspended since 8 August 2019. The itinerary begins in Lahore, and proceeds into India. Later the itinerary mentions some further destinations in present-day Pakistan, but if you plan to visit these too it might be wise to do that at the beginning of your trip so you'll have to experience any border hassle only once and can travel on single-entry visas (almost everyone needs a visa both for Pakistan and India).

In order to make the itinerary as close as possible to Kim's you may want to travel by train rather than flying. Most of the destinations are on a train line, but in the Himalayan North bus is the way to get around. Budget at least a couple of weeks to travel this itinerary.

The story begins

The story opens with Kim atop the great gun in the bazaar at Lahore 📍, in today's Pakistan. Lahore was briefly the capital of the Mughal Empire in the 16th century and contains some fine architecture in the distinctive Islamic Mughal style. In the first half of the nineteenth century, it served as the capital of an independent Sikh Punjab Kingdom, then after two Anglo-Sikh wars in the 1860s it became the capital of the British Raj's Punjab Province. Today the Punjab is divided between India and Pakistan, and Lahore is the capital of Pakistan's Punjab Province.

The story opens with Kim atop the great gun in the bazaar at Lahore 📍, in today's Pakistan. Lahore was briefly the capital of the Mughal Empire in the 16th century and contains some fine architecture in the distinctive Islamic Mughal style. In the first half of the nineteenth century, it served as the capital of an independent Sikh Punjab Kingdom, then after two Anglo-Sikh wars in the 1860s it became the capital of the British Raj's Punjab Province. Today the Punjab is divided between India and Pakistan, and Lahore is the capital of Pakistan's Punjab Province.

Kim's full name is Kimball O'Hara; he may look like just another bazaar brat and speak Urdu better than English, but he is the son of an Irish sergeant who left the army, stayed in India, took to drink and opium, and died as poor whites die in India. Kim's mother, an Irish maid in a colonel's house, died even earlier of cholera (a scourge in those days among both Indians and British) in a town Kipling called Ferozpore, then a major British military base. Today is it called Firozpur, is in India's Punjab Province near the border with Pakistan, and is still an important military base.

Kim, in his early teens as the story opens, knows only that his father's estate at death consisted of three papers ... On no account was Kim to part with them, ...It would, he said, all come right some day ... The Colonel himself ... <nowiki>[and]</nowiki> Nine hundred first-class devils, whose God was a Red Bull on a green field, would attend to Kim, if they had not forgotten O'Hara. Kim carries the papers in a pouch around his neck and considers them magical; he has little idea of their real significance.

Kim and friends are hanging about in the bazaar, outside the old Ajaib-Gher—the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum (see Lahore#Museums), when an unusual person appears, a man as Kim, who thought he knew all castes, had never seen. ... At his belt hung a long open-work iron pencase and a wooden rosary such as holy men wear. On his head was a gigantic sort of tam-o'-shanter.

The old man turns out to be a Tibetan lama, abbot of a monastery he calls Such-zen. It is not clear where this would be, or even whether it is real or fictional, but the lama mentions a four-month march via Kulu and Pathankot which places it in Western Tibet, likely Nyingchi Prefecture. He is on a pilgrimage to the places of the Buddha's life and to find a legendary holy river. He has come via Lahore in order to see the museum's fine collection of Buddhist sculpture, mostly from excavations at the ancient city of Taxila.

Kim guides him into the museum, then listens at the door as the old man chats with the British curator. He learns of the lama's journey and that the old fellow's chela (disciple and student) died of fever in Kulu. He determines to volunteer as a new chela and join the journey, searching for his own red bull on a green field along the way. The lama accepts and Kim begins his duties as chela by begging dinner for both of them.

It is interesting to speculate on whether, or to what extent, characters in the book are based on Kipling's own experiences or on his family. Kipling himself grew up in Lahore, and his father was the curator of the Lahore Museum.

The journey East

The lama's goal is to reach Benares (now known as Varanasi), the holiest city of Hinduism, and use that as a base to visit sites related to the Buddha's life such as Lumbini (where he grew up), Bodh Gaya (where he reached enlightenment), and Kushinagar (where he died). Along the way, he will search for his river and Kim for his bull.

Before setting out they must sleep, so Kim leads the lama to the Kashmir Serai: that huge open square over against the railway station, surrounded with arched cloisters, where the camel and horse caravans put up on their return from Central Asia. Kashmir is another former province of the Raj, located North of the Punjab. It too is now divided, with Jammu and Kashmir on the Indian side and Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. Neither national government accepts the current dividing line; each claims territory currently controlled by the other.

Kim has a friend at the serai, a big burly Afghan horse trader named Mahbub Ali. Mahbub is a Pathan, a Pushtu speaker; Pathan territory is on both sides of the border between Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier Province of the Raj, now Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Like the Scots, Sikhs and Gurkhas, the Pathans resisted the English or British quite fiercely at one time and later, after being defeated, provided some of the Empire's finest troops; the Pathan regiments were nearly all cavalry.

Kim has a friend at the serai, a big burly Afghan horse trader named Mahbub Ali. Mahbub is a Pathan, a Pushtu speaker; Pathan territory is on both sides of the border between Afghanistan and the North-West Frontier Province of the Raj, now Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Like the Scots, Sikhs and Gurkhas, the Pathans resisted the English or British quite fiercely at one time and later, after being defeated, provided some of the Empire's finest troops; the Pathan regiments were nearly all cavalry.

Mahbub is a Moslem like nearly all Pathans, and a Hajji who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca. Seeing the lama's begging bowl, he responds with God's curse on all unbelievers! I do not give to a lousy Tibetan; but ask my Baltis over yonder behind the camels. They may value your blessings. Most of his crew are hillmen from Baltistan; Kipling describes them as nominally some sort of degraded Buddhist and they treat the lama with awed respect.

We learn that Kim had had many dealings with Mahbub ... <nowiki>[who]</nowiki> knew the boy's value as a gossip. Sometimes he would tell Kim to watch a man who had nothing whatever to do with horses ... It was intrigue of some kind, Kim knew; but its worth lay in saying nothing whatever to anyone except Mahbub. This time, Mahbub entrusts Kim with a secret message for a British officer in Umballa, now called Ambala. On the surface, the message confirms the pedigree of a stallion, but Kim knows that is just a cover for some intrigue.

They get on train to Umballah and Kipling gives us a comic interlude with a cast of characters from all over the Punjab — a farmer and his wife from Jalandhar, a fat Hindu money lender, a courtesan from Amritsar, a Sikh soldier from Ludhiana, a Dogra soldier from around Jammu and various others.

First you need to cross the border to India. The nearby Attari/Wagah crossing is the only one between the countries regularly open for foreigners. The bi-weekly Samjhauta Express uses this crossing, and you can take this train to Amritsar and another to Ambala. There are more than a dozen daily trains from Amritsar to Ambala with travel time ranging from 3.5 to 7 hours. Driving, one might take the Grand Trunk Road since Lahore, Amritsar and Ambala are all on it.

First you need to cross the border to India. The nearby Attari/Wagah crossing is the only one between the countries regularly open for foreigners. The bi-weekly Samjhauta Express uses this crossing, and you can take this train to Amritsar and another to Ambala. There are more than a dozen daily trains from Amritsar to Ambala with travel time ranging from 3.5 to 7 hours. Driving, one might take the Grand Trunk Road since Lahore, Amritsar and Ambala are all on it.

If the Samjhauta Express service is suspended, there might be a through bus to Amritsar, alternatively you can take a bus or taxi to the border, walk across, and take another bus or taxi to Amritsar. If the border crossing is entirely closed, you're in for a ridiculously long detour because as of 2019 there are no flights between the two countries. The shortest way would be flying from Lahore to Dubai, and from there to Amritsar (to continue by train), or to Chandigarh airport which also serves Ambala.

On arrival in Umballah 📍, the holy man and disciple are invited by the farmer's wife to join them in staying at a cousin's house. Once the lama is settled there, Kim goes off to deliver Mahbub's message to the British officer; then he hides in the bushes to see what effect it has. Every time before that I have borne a message it concerned a woman. Now it is men. Better. The tall man said that they will loose a great army to punish someone—somewhere—the news goes to Pindi and Peshawur. He also discovers that the tall man is the Commander-in-chief. "Pindi" or Rawalpindi and Peshawar are the main cities of the North-West Frontier Province along the perennially troublesome Afghan border.

On arrival in Umballah 📍, the holy man and disciple are invited by the farmer's wife to join them in staying at a cousin's house. Once the lama is settled there, Kim goes off to deliver Mahbub's message to the British officer; then he hides in the bushes to see what effect it has. Every time before that I have borne a message it concerned a woman. Now it is men. Better. The tall man said that they will loose a great army to punish someone—somewhere—the news goes to Pindi and Peshawur. He also discovers that the tall man is the Commander-in-chief. "Pindi" or Rawalpindi and Peshawar are the main cities of the North-West Frontier Province along the perennially troublesome Afghan border.

From Umballah, they continue afoot; a helpful old soldier guides them onto the Grand Trunk Road, the great road all the way from Calcutta to Kabul built by Indian kings before the British arrived. There things get very colourful indeed; all India can be seen on that road. And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India's traffic for fifteen hundred miles—such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world. They looked at the green-arched, shade-flecked length of it, the white breadth speckled with slow-pacing folk...

In some ways, this is the best part of the book; Kipling's descriptions are brilliant. However, we will skip over it because it contains no definite destinations.

Along the way, they meet a distinctly feisty old lady, a hill woman from the Kulu region who has married into a plains family in Oudh (later amalgamated with Agra Province to form what is now Uttar Pradesh) and is now a widow. She is travelling with a retinue, some of whom are her own hill folk; they and their mistress are awed by the presence of the lama. Others are some of her husband's retainers who Kipling describes as Oorya; today we would call them Odia.

The lama and Kim agree to join her party and continue toward her home near Saharunpore 📍, up at the Northern tip of Uttar Pradesh.

Kim finds his red bull

As it turns out, though, Kim does not make it all the way to Saharunpore. One evening en route, Kim and the lama go for a walk before dinner and notice some soldiers, an advance guard going ahead of their regiment to mark the camp site. Then Kim pointed to the flag ... It was no more than an ordinary camp marking-flag; but the regiment ... had charged it with the regimental device, the Red Bull, which is the crest of the Mavericks—the great Red Bull on a background of Irish green. This is of course Kim's prophecy. A bit later, the whole regiment arrives and pitches camp.

Kim and the lama go back to their own camp for dinner, then return to have a better look at the military camp. Kim leaves the lama concealed nearby and sneaks in for a better look. He is caught by the regiment's Church of England padre who finds Kim's documents — his father's military discharge and masonic membership plus Kim's birth certificate — and summons the regiment's Catholic chaplain to help him figure out why on Earth an apparent thief speaks English and has these documents. Kim calls the lama to join them and explains I have found the Bull, but God knows what comes next. .... Come to the fat priest's tent with this thin man and see the end. ... they cannot talk Hindi. They are only uncurried donkeys.

The lama joins them and there is a discussion involving Kim and three religious men. Kim acts as translator: Holy One, the thin fool who looks like a camel says that I am the son of a Sahib... he could only find it out by rending the amulet from my neck and reading all the papers. .. between the two of them they purpose to keep me in this Regiment or to send me to a madrissah [a school]. It has happened before. I have always avoided it. The lama inquires about the cost of education and which is the best school. Father Victor replies The Regiment would pay for you ... at the Military Orphanage; ... but the best schooling a boy can get in India is, of course, at St Xavier's in Partibus at Lucknow. He then asks how much, is told 300 rupees a year and Kim translates the reply: He says: "Write that name and the money upon a paper and give it him." And he says you must write your name below, because he is going to write a letter in some days to you. He says you are a good man. He says the other man is a fool. He is going away.

Kim is left with the regiment, given Western clothes which he does not like, sent to a school which he likes even less, and thrown in with the drummer boys, one of whom is assigned to watch him. He does manage to get a letter off to Mahbub Ali. He walked out of afternoons under escort of the drummer-boy ... The boy resented his silence and lack of interest by beating him, as was only natural. ... On the morning of the fourth day a judgement overtook that drummer. They had gone out together towards Umballa racecourse. He returned alone, weeping, with news that young O'Hara, to whom he had been doing nothing in particular, had hailed a scarlet-bearded nigger on horseback; that the nigger had then and there laid into him with a peculiarly adhesive quirt, picked up young O'Hara, and borne him off at full gallop.

Kim is left with the regiment, given Western clothes which he does not like, sent to a school which he likes even less, and thrown in with the drummer boys, one of whom is assigned to watch him. He does manage to get a letter off to Mahbub Ali. He walked out of afternoons under escort of the drummer-boy ... The boy resented his silence and lack of interest by beating him, as was only natural. ... On the morning of the fourth day a judgement overtook that drummer. They had gone out together towards Umballa racecourse. He returned alone, weeping, with news that young O'Hara, to whom he had been doing nothing in particular, had hailed a scarlet-bearded nigger on horseback; that the nigger had then and there laid into him with a peculiarly adhesive quirt, picked up young O'Hara, and borne him off at full gallop.

It is common even today, for a Hajji, someone who has made the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, to dye his beard red.

These tidings came to Father Victor, ... He was already sufficiently startled by a letter from the Temple of the Tirthankars at Benares, enclosing a native banker's note of hand for three hundred rupees.

Meanwhile, Mahbub Ali is explaining to Kim ... there is my honour and reputation to be considered. All the officer-Sahibs in all the regiments, and all Umballa, know Mahbub Ali. Men saw me pick thee up and chastise that boy. ... How can I take thee away ...? They would put me in jail. Be patient. Then the Englishman to whom Kim delivered the message in Umballah appears and inquires about the lad. As they are discussing things, Father Victor appears and the other Englishman introduces himself as Creighton of the Ethnological Survey. The priest is much relieved: You'll be the one man that could help me in my quandaries. Tell you! Powers o' Darkness, I'm bursting to tell someone who knows something o' the native!'.

Creighton suggests I—er—strongly recommend sending the boy to St Xavier's. ... It's perfectly easy. I've got to go down to Lucknow next week. I'll look after the boy on the way—give him in charge of my servants, and so on. However, Creighton has a request for Father Victor: There's one thing you can do. All we Ethnological men are as jealous as jackdaws of one another's discoveries. ... Well, don't say a word, directly or indirectly, about the Asiatic side of the boy's character—his adventures and his prophecy, and so on. The priest readily agrees. Before departing, Creighton also cautions Kim not to run away yet. <nowiki>'I will wait,' said Kim, 'but the boys will beat me.'</nowiki>

Later Kim goes to the bazaar to send a letter to the lama and Creighton appears. Kim asks the letter writer who that is and is told Oh, he is only Creighton Sahib—a very foolish Sahib, who is a Colonel Sahib without a regiment. Kim thinks differently: fools are not given information which leads to calling out eight thousand men besides guns. The Commander-in-Chief of all India does not talk, as Kim had heard him talk, to fools. Nor would Mahbub Ali's tone have changed, as it did every time he mentioned the Colonel's name, if the Colonel had been a fool. Consequently—and this set Kim to skipping—there was a mystery somewhere, and Mahbub Ali probably spied for the Colonel much as Kim had spied for Mahbub. ... Here was a man after his own heart—a tortuous and indirect person playing a hidden game.

A few days later, they set off by train for Lucknow 📍, capital of Uttar Pradesh and one of the main cultural and artistic centers of North India. Saint Xavier's school is located there, in a suburb called Nucklao. Presently the Colonel sent for him, and talked for a long time. ... Kim pretended at first to understand perhaps one word in three of this talk. Then the Colonel, seeing his mistake, turned to fluent and picturesque Urdu and Kim was contented. No man could be a fool who knew the language so intimately, who moved so gently and silently, and whose eyes were so different from the dull fat eyes of other Sahibs.

Kim planned going to Saharunpore, but ended up in Lucknow instead. From Ambala Cantonment Junction there are multiple daily trains to Lucknow, travel time 10–15 hours. Saharunpore is also along the same route, and trains stop there too, though the itinerary will return back to Saharunpore later on.

At the school

Kim reaches St Xavier's school, after a stop to talk with his lama who is waiting near the gate. Kipling gives an interesting description of Kim's fellow students:

They were sons of subordinate officials ... of captains of the Indian Marine, Government pensioners, planters, Presidency shopkeepers, and missionaries. A few were cadets of the old Eurasian houses ... Their homes ranged from Howrah of the railway people to abandoned cantonments ...; lost tea-gardens Shillong-way; villages where their fathers were large landholders ...; Mission-stations a week from the nearest railway line; seaports a thousand miles south, facing the brazen Indian surf; and cinchona-plantations south of all.

These are all over India. Howrah is near Calcutta and Shillong even further east. Chinchona is the bark that gives the anti-malarial drug quinine; the British introduced it to Asia and it was extensively cultivated in Sri Lanka and Southern India.

The mere story of their adventures, which to them were no adventures, on their road to and from school would have crisped a Western boy's hair. They were used to jogging off alone through a hundred miles of jungle, where there was always the delightful chance of being delayed by tigers; but they would no more have bathed in the English Channel in an English August than their brothers across the world would have lain still while a leopard snuffed at their palanquin. There were boys of fifteen who had spent a day and a half on an islet in the middle of a flooded river, taking charge, as by right, of a camp of frantic pilgrims returning from a shrine. There were seniors who had requisitioned a chance-met Rajah's elephant, in the name of St Francis Xavier, when the Rains once blotted out the cart-track that led to their father's estate, and had all but lost the huge beast in a quicksand. There was a boy who, he said, and none doubted, had helped his father to beat off with rifles from the veranda a rush of Akas in the days when those head-hunters were bold against lonely plantations.

The Aka or Hrusso are a tribe in the extreme East of India, in Arunachal Pradesh.

The first summer holiday

Then came the holidays from August to October—the long holidays imposed by the heat and the Rains. Kim was informed that he would go north ... where Father Victor would arrange for him. ...

Kim considered it in every possible light. He had been diligent, even as the Colonel advised. A boy's holiday was his own property—of so much the talk of his companions had advised him, ... No word had come from the lama, but there remained the Road. Kim yearned for the caress of soft mud squishing up between the toes, as his mouth watered for mutton stewed with butter and cabbages, for rice speckled with strong scented cardamoms, for the saffron-tinted rice, garlic and onions, and the forbidden greasy sweetmeats of the bazars.

Kim takes off on his own for a while, going back to Umballa, making his first visit to Delhi 📍, and visiting the princely state of Patiala 📍 in the Punjab. The British ruled only about half of India directly; the rest was a collection of several hundred princely states, each with its own raja. These ranged from tiny places up to some the size of France; Patiala was not remarkably large, but it was rich and fairly important. Kim then hooks up with Mahbub Ali again, asking him if there has been a fault, let the Hand of Friendship turn aside the Whip of Calamity that is, please intercede with the colonel to get Kim off the hook for taking some time off. Mahbub does that, and the two begin to travel together.

The Pathan has a caravan of horses, and they head North via Kalka 📍 to Simla 📍, a hill station that was the summer capital of the Raj. There they part company as Mahbub, over Kim's objections, send him off to stay with a local resident: Lurgan Sahib has a shop among the European shops. All Simla knows it. Ask there ... and, Friend of all the World, he is one to be obeyed to the last wink of his eyelashes. Men say he does magic, but that should not touch thee. Go up the hill and ask. Here begins the Great Game.

Lurgan Shaib does do something like magic; he is the healer of pearls, fixing flaws in various gems. He sells Indian and Tibetan curios to Europeans, Western gadgets like clocks and record players to Maharajas, and gems to both. He also trains Kim in a variety of skills, first telling his other apprentice Play the Play of the Jewels against him. He gives both boys a quick look at a tray with fifteen gems, covers it, and requires them to report what was there; the other lad wins easily and repeatedly. Then The Hindu boy, in highest feather, actually patted Kim on the back. "Do not despair," he said. "I myself will teach thee."

Lurgan Shaib does do something like magic; he is the healer of pearls, fixing flaws in various gems. He sells Indian and Tibetan curios to Europeans, Western gadgets like clocks and record players to Maharajas, and gems to both. He also trains Kim in a variety of skills, first telling his other apprentice Play the Play of the Jewels against him. He gives both boys a quick look at a tray with fifteen gems, covers it, and requires them to report what was there; the other lad wins easily and repeatedly. Then The Hindu boy, in highest feather, actually patted Kim on the back. "Do not despair," he said. "I myself will teach thee."

They also practice acting and disguise: After dinner, Lurgan Sahib's fancy turned more to what might be called dressing-up ... He could paint faces to a marvel; with a brush-dab here and a line there changing them past recognition. The shop was full of all manner of dresses and turbans, and Kim was apparelled variously as a young Mohammedan of good family, an oilman, and once—which was a joyous evening—as the son of an Oudh landholder in the fullest of full dress. Lurgan Sahib had a hawk's eye to detect the least flaw in the make-up; and lying on a worn teak-wood couch, would explain by the half-hour together how such and such a caste talked, or walked, or coughed, or spat, or sneezed, and, since 'hows' matter little in this world, the 'why' of everything.

While at Lurgan Sahib's, Kim also meets a character who will be important later: Carried away by enthusiasm, he volunteered to show Lurgan Sahib one evening how the disciples of a certain caste of fakir, old Lahore acquaintances, begged doles by the roadside; ... Lurgan Sahib laughed immensely, and begged Kim to stay as he was, immobile for half an hour — cross-legged, ash-smeared, and wild-eyed, in the back room. At the end of that time entered a hulking, obese Babu whose stockinged legs shook with fat, and Kim opened on him with a shower of wayside chaff. Lurgan Sahib—this annoyed Kim—watched the Babu and not the play.

"Babu" is originally an honorific derived from the Sanskrit for father, but in British India it was "a derogatory word signifying a semi-literate native, with a mere veneer of modern education" (Wikipedia). Superficially at least, Hurree Chunder Mookerjee is a typical example of the breed, a foolish and officious clerk. However, he is also another player in the Great Game.

Going back and forth between Lucknow and these destinations and the ones in the following section would not be a very logical way to travel. A couple of them will be visited later in the itinerary, the rest you can fit into your journey towards the end (the ones in India) or beginning of the trip (the ones in Pakistan).

Other travels

For the next three years, Kim has an interesting mixture of activities in his life. Much of the time, he is a (mostly) proper young sahib at the school: he showed a great aptitude for mathematical studies as well as map-making, ... and the same term played in St Xavier's eleven ...

In the holidays, however, he gets rather different training from Lurgan Sahib. He made Kim learn whole chapters of the Koran by heart, till he could deliver them with the very roll and cadence of a mullah. Moreover, he told Kim the names and properties of many native drugs, as well as the runes proper to recite when you administer them.

He also travels some with Mahbub, going to Quetta 📍 where Kim does his first bit of actual spying, working as a scullion in a local merchant's house until he can lay hands on and copy a ledger which Mahbub wants. They then go down to Karachi 📍 and by sea to Bombay 📍; the adventurous Kim suggests a trip to Arabia to buy the famous Arab horses, but Mahbub refuses.

Kim pleases his various trainers and receives gifts from them, partly as reward for his efforts. Hurree Babu provides him with a box of medicines and Mahbub gives him a fine Pathan costume and a mother-of-pearl, nickel-plated, self-extracting .450 revolver.

As Kim nears sixteen, there is a discussion among the trainers of what the lad might do next. "There is no holding the young pony from the game," said the horse-dealer when the Colonel pointed out that vagabonding over India in holiday time was absurd. "If permission be refused to go and come as he chooses, he will make light of the refusal. Then who is to catch him? Colonel Sahib, only once in a thousand years is a horse born so well fitted for the game as this our colt. And we need men."

One mission is proposed and rejected: "There is a little business where he would be most useful—in the South," said Lurgan ... "Only tell him the shape and the smell of the letters we want and he will bring them back" ... "No. That is a man's job," said Creighton. Then a more acceptable alternative is found: "Let him go out with his Red Lama," said the horse-dealer ... "Very good, then," said Creighton, half to himself. "He can go with the lama, and if Hurree Babu cares to keep an eye on them so much the better."

With the lama again

A letter comes to the school, Colonel Creighton offering Kim a job as a junior surveyor, and the school of course releases him. Mahbub leads him to a witch who dyes his skin darker and sets various charms to protect him on the road. He then leaves him with Hurree Babu, who has been sitting in a corner taking anthropological notes for yet another paper which he can submit as part of his continuing effort to fulfill his great ambition, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society.

A letter comes to the school, Colonel Creighton offering Kim a job as a junior surveyor, and the school of course releases him. Mahbub leads him to a witch who dyes his skin darker and sets various charms to protect him on the road. He then leaves him with Hurree Babu, who has been sitting in a corner taking anthropological notes for yet another paper which he can submit as part of his continuing effort to fulfill his great ambition, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society.

The babu tells Kim: If you feel in your neck you will find one small silver amulet, verree cheap. That is ours. ... when we get them we put in, before issue, one small piece of turquoise. ... Suppose we get into a dam'-tight place. I am a fearful man—most fearful—but I tell you I have been in dam'-tight places more than hairs on my head. You say: "I am Son of the Charm." ... and perhaps before they jolly-well-cut-your-throat they may give you just a chance of life ... these foolish natives—if they are not too excited—they always stop to think before they kill a man who says he belongs to any speecific organization. He also teaches him a dialogue that can serve as a way of identifying secret colleagues.

Kim finds his lama at the temple in Benares 📍; outside is a Punjabi farmer with a sick child, desperately searching for a priest who can effect a cure. To the surprise of both farmer and lama, Kim is able to help out using some of the medicines in the little kit Hurree Babu gave him.

From Lucknow, further in the same direction is Varanasi, with almost 30 daily services on different train types. Travel time is 4:40 to 10 hours.

Lama and chela retire to the lama's cell where: He drew from under the table a sheet of strangely scented yellow Chinese paper, the brushes, and slab of Indian ink. In cleanest, severest outline he had traced the Great Wheel with its six spokes, ... Many ages have crystallized it into a most wonderful convention crowded with hundreds of little figures whose every line carries a meaning. Few can translate the picture-parable; there are not twenty in all the world who can draw it surely without a copy: of those who can both draw and expound are but three. The lama, it seems, is one of the three and he undertakes to teach Kim the art.

Lama and chela retire to the lama's cell where: He drew from under the table a sheet of strangely scented yellow Chinese paper, the brushes, and slab of Indian ink. In cleanest, severest outline he had traced the Great Wheel with its six spokes, ... Many ages have crystallized it into a most wonderful convention crowded with hundreds of little figures whose every line carries a meaning. Few can translate the picture-parable; there are not twenty in all the world who can draw it surely without a copy: of those who can both draw and expound are but three. The lama, it seems, is one of the three and he undertakes to teach Kim the art.

The lama decides to head North, toward the cool of the hills. They board the train toward Delhi, then have a strange encounter: There tumbled into the compartment ... a mean, lean little person ... His face was cut, his muslin upper-garment was badly torn, and one leg was bandaged. He told them that a country-cart had upset and nearly slain him: ... Kim watched him closely ... a mere fall from a cart could not cast a man into such extremity of terror. As, with shaking fingers, he knotted up the torn cloth about his neck he laid bare an amulet ... Now, amulets are common enough, but they are not generally strung on square-plaited copper wire, and still fewer amulets bear black enamel on silver. ... Kim made as to scratch in his bosom, and thereby lifted his own amulet. The Mahratta's face changed altogether at the sight, and he disposed the amulet fairly on his breast. From there, a bit of rigamarole about the Son of the Charm suffices for Kim and the stranger to identify each other as servants of a common cause.

The stranger explains: I come from the South, where my work lay. One of us they slew by the roadside. ... Having found a certain letter which I was sent to seek, I came away. He has travelled via Mhow, Chittoor (where he hid the letter), Bandakui and Agra, and has been pursued all the way by enemies who falsely accuse him of various crimes in order to extradite him to the South. He fully expects to be apprehended on the platform at Delhi, to be extradited and then to die a lingering death as an example to others.

Kim's response is We must make thee a yellow Saddhu all over. Strip—strip swiftly, and shake thy hair over thine eyes while I scatter the ash. Now, a caste-mark on thy forehead. After a few minutes: In place of the tremulous, shrinking trader there lolled against the corner an all but naked, ash-smeared, ochre-barred, dusty-haired Saddhu, his swollen eyes—opium takes quick effect on an empty stomach—luminous with insolence and bestial lust, his legs crossed under him, Kim's brown rosary round his neck, and a scant yard of worn, flowered chintz on his shoulders.

It works; they reach Delhi 📍 and indeed find police on the platform searching for the fugitive, but the apparent sadhu does not match the description so he is able to escape their scrutiny.

There are several daily trains from Varanasi to different stations in the capital. Depending on the train type, travel time varies between 8 and almost 18 hours.

Back to Saharunpore

Kim and the lama change trains and go on toward Saharunpore 📍, planning to again enjoy the hospitality of the Kulu woman they met previously on the Grand Trunk Road. During the long walk from Saharunpore station to her home, they have time to become reacquainted. Kim asks I ate thy bread for three years—as thou knowest. Holy One, whence came—? and the lama replies There is much wealth, as men count it, in Bhotiyal ... In my own place I have the illusion of honour. I ask for that I need. I am not concerned with the account. That is for my monastery.

Bhotiyal is a Tibetan term for Tibet, now archaic.

There are several daily trains to Saharunpore, travel time generally between three and four hours. Depending on the train, it may depart from Old Delhi (DLI), New Delhi (NDLS) or Hazrat Nizamuddin Station (NZM).

At the house, Kim learns there is a new hakim (herbal medicine practitioner) in the area: A wanderer, as thou art, but a most sober Bengali from Dacca—a master of medicine. ... He travels about now, vending preparations of great value. ... He has been here four days; but hearing ye were coming (hakims and priests are snake and tiger the world over) he has, as I take it, gone to cover. ... Kim bristled like an expectant terrier. To outface and down-talk a Calcutta-taught Bengali, a voluble Dacca drug-vendor, would be a good game. It was not seemly that the lama, and incidentally himself, should be thrown aside for such an one.

Dacca, now spelt Dhaka, was one of the most important cities in the Raj's province of Bengal. Today, that province has been split into India's province of West Bengal and the separate country of Bangladesh whose capital is Dhaka.

When the hakim appears, a few distinctly barbed comments are exchanged, then: Said the hakim, hardly more than shaping the words with his lips: "How do you do, Mister O'Hara? I am jolly glad to see you again." Kim's hand clenched about the pipe-stem. Anywhere on the open road, perhaps, he would not have been astonished; but here, in this quiet backwater of life, he was not prepared for Hurree Babu. It annoyed him, too, that he had been hoodwinked.

Hurree continues I come to congratulate you on your extraordinary effeecient performance at Delhi. ... Our mutual friend, he is old friend of mine. ... He told me; I tell Mr Lurgan; and he is pleased you graduate so nicely. All the Department is pleased. ... and I had to go down to Chitor to find that beastly letter. I do not like the South—too much railway travel; but I drew good travelling allowance.

However, there is still a problem in the North: There were Five Kings who prepared a sudden war three years ago, when thou wast given the stallion's pedigree by Mahbub Ali. Upon them, because of that news, and ere they were ready, fell our Army. ... But the ... troops were recalled because the Government believed the Five Kings were cowed; and it is not cheap to feed men among the high Passes. ... I, who had been selling tea in Leh, became a clerk of accounts in the Army. When the troops were withdrawn, I was left behind to pay the coolies who made new roads in the Hills.

Leh is the capital of Ladakh, a beautiful region far to the North. It is almost at the border with China and on a caravan trail that leads there, one branch of the ancient Silk Road.

There are Russians loose in the area: I send word many times that these two Kings were sold to the North; and Mahbub Ali, who was yet farther North, amply confirmed it. Nothing was done. ... Over the Passes this year after snow-melting ... come two strangers under cover of shooting wild goats. They bear guns, but they bear also chains and levels and compasses. ... They are well received ... They make great promises; they speak as the mouthpiece of a Kaisar with gifts. Up the valleys, down the valleys go they, saying, "Here is a place to build a breastwork; here can ye pitch a fort. Here can ye hold the road against an army"—the very roads for which I paid out the rupees monthly. The Government knows, but does nothing.

Huree Babu is being sent North to keep an eye on these fellows: I go from here straight into the Doon. ... I shall go to Mussoorie ... That is the only way they can come. I do not like waiting in the cold, but we must wait for them. I want to walk with them to Simla. You see, one Russian is a Frenchman, and I know my French pretty well. I have friends in Chandernagore.

The Doon is the valley around Dehradun in Uttarakhand state, and Mussoorie 📍 is a hill station in that area. Chandernagore is a former French colony near Calcutta. Simla was the summer capital of the Raj; today it is spelt Shimla, and is the capital of Himachal Pradesh.

First, travel to Dehradun. There are a few trains a day with travel times ranging from 2.5–5.5 hours. There are also two buses a day, with the trip taking just 2 hours (no surprise as the railway takes a long detour). From Dehradun there are buses to Mussoorie, alternatively you can travel the around 40 km distance by taxi.

However, They are Russians, and highly unscrupulous people. I—I do not want to consort with them without a witness. ... I am good enough Herbert Spencerian, I trust, to meet little thing like death, which is all in my fate, you know. But—but they may beat me. ... I am, oh, awfully fearful!—I remember once they wanted to cut off my head on the road to Lhassa ... I sat down and cried, Mister O'Hara, anticipating Chinese tortures. I do not suppose these two gentlemen will torture me, but I like to provide for possible contingency with European assistance in emergency.

It is not difficult for Kim and Hurree to persuade the lama that a return to the hills would be a fine idea — Hurree prescribes it for his health and Kim wants to explore. At noon the Babu strapped up his brass-bound drug-box, took his patent-leather shoes of ceremony in one hand, a gay blue-and-white umbrella in the other, and set off northwards to the Doon, where, he said, he was in demand among the lesser kings of those parts. Kim and the lama follow later.

The Great Game

After a few days, They had ..., left Mussoorie behind them, and headed north along the narrow hill-roads. but according to the lama These are but the lower hills, chela.

They do not travel with the babu but, Fate sent them, overtaking and overtaken upon the road, the courteous Dacca physician, who paid for his food in ointments ... He seemed to know these hills as well as he knew the hill dialects He has a request: You see, Mister O'Hara, I do not know what the deuce-an' all I shall do when I find our sporting friends; but if you will kindly keep within sight of my umbrella, which is fine fixed point for cadastral survey, I shall feel much better.

As for the Russians, They were at Leh not so long ago. ... They should have come in by Srinagar or Abbottabad. That is their short road ... But they have made mischief in the West. So ... they march and they march away East to Leh (ah! it is cold there), and down the Indus ... Our friends have been a long time playing about and producing impressions. So they are well known from far off. You will see me catch them somewhere in Chini valley. Please keep your eye on the umbrella.

Abbottabad is a town well to the West in Pakistan, in Pathan territory. It was named after a British officer and, until the Karakoram Highway bypassed it, was a key junction on routes North to Baltistan and China. In 2011, it was in the news as the place where Osama bin Laden was tracked down and killed. Srinagar, now the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, is further East and Leh further yet. The Chini valley is now known as Kinnaur 📍 and is in Himachal Pradesh.

Return to Dehradun, and take a bus to Shimla (8 hours, one daily bus), and from there another bus to Reckong Peo (9 hours, one daily bus), the headquarters of the Kinnaur district.

At last they entered a world within a world—a valley of leagues where the high hills were fashioned of a mere rubble and refuse from off the knees of the mountains. ... Above them, still enormously above them, earth towered away towards the snow-line, where from east to west across hundreds of miles, ruled as with a ruler, the last of the bold birches stopped. ... Above these again, changeless since the world's beginning, but changing to every mood of sun and cloud, lay out the eternal snow.

The enemy appears: Hurree was ... 'fairly effeecient stalker', and he had raked the huge valley with a pair of cheap binoculars ... Hurree Babu had seen all he wanted to see ... [and soon] an oily, wet, but always smiling Bengali, talking the best of English with the vilest of phrases, was ingratiating himself with two sodden and rather rheumatic foreigners [whose] dozen or two forcibly impressed baggage-coolies had fled after the strange Sahibs had already threatened them with rifles ... they had never been thus treated in their lives.

The babu claims to be agent for His Royal Highness, the Rajah of Rampur (probably Rampur (Himachal Pradesh)), and the Russians are delighted. He offers assistance, and sets about ingratiating himself. Soon he waylaid a cowering hillman among the trees, and after three minutes' talk and a little silver ... the eleven coolies and the three hangers-on reappeared.

The porters remain suspicious: All the Sahibs of their acquaintance ...had servants and cooks and orderlies, very often hillmen. These Sahibs travelled without any retinue. Therefore they were poor Sahibs, and ignorant; for no Sahib in his senses would follow a Bengali's advice. But the Bengali, appearing from somewhere, had given them money, and could make shift with their dialect. Used to comprehensive ill-treatment from their own colour, they suspected a trap somewhere, and stood by to run if occasion offered.

The travellers do trust the Bengali as guide but Under the striped umbrella Hurree Babu was straining ear and brain to follow the quick-poured French, and keeping both eyes on a kilta full of maps and documents — an extra-large one with a double red oil-skin cover. He did not wish to steal anything. He only desired to know what to steal, and, incidentally, how to get away when he had stolen it. He thanked all the Gods of Hindustan, and Herbert Spencer, that there remained some valuables to steal.

On the second day ... they came across an aged lama ... sitting cross-legged above a mysterious chart held down by stones, which he was explaining to a young man, evidently a neophyte, of singular, though unwashen, beauty. The striped umbrella had been sighted half a march away, and Kim had suggested a halt till it came up to them. The lama has drawn the Wheel and is expounding it to his chela. The Russians are greatly impressed by the art, if not the exposition. I cannot understand him, but I want that picture. He is a better artist than I. Ask him if he will sell it. The lama shook his head slowly and began to fold up the Wheel.

The Russian, on his side, saw no more than an unclean old man haggling over a dirty piece of paper. He drew out a handful of rupees, and snatched half-jestingly at the chart, which tore in the lama's grip. A low murmur of horror went up from the coolies ... The lama rose at the insult ... and the Babu danced in agony. ... the Russian struck the old man full on the face. Next instant he was rolling over and over downhill with Kim at his throat. The blow had waked every unknown Irish devil in the boy's blood ...

The lama dropped to his knees, half-stunned; the coolies under their loads fled up the hill as fast as plainsmen run aross the level. They had seen sacrilege unspeakable, and it behoved them to get away before the Gods and devils of the hills took vengeance. The Frenchman ran towards the lama, fumbling at his revolver with some notion of making him a hostage for his companion. A shower of cutting stones—hillmen are very straight shots—drove him away, and a coolie from Ao-chung snatched the lama into the stampede. All came about as swiftly as the sudden mountain-darkness.

"They have taken the baggage and all the guns," yelled the Frenchman, firing blindly into the twilight. "All right, sar! All right! Don't shoot. I go to rescue," and Hurree, pounding down the slope, cast himself bodily upon the delighted and astonished Kim, who was banging his breathless foe's head against a boulder. "Go back to the coolies," whispered the Babu in his ear. "They have the baggage. The papers are in the kilta with the red top"

"They have taken the baggage and all the guns," yelled the Frenchman, firing blindly into the twilight. "All right, sar! All right! Don't shoot. I go to rescue," and Hurree, pounding down the slope, cast himself bodily upon the delighted and astonished Kim, who was banging his breathless foe's head against a boulder. "Go back to the coolies," whispered the Babu in his ear. "They have the baggage. The papers are in the kilta with the red top"

The lama, not without difficulty, talks the crew of hillmen out of their immediate impulse to kill the perpetrators of sacrilege; instead the Russians are left to their own (and the Babu's) devices. Everyone else sets off for Shamlegh-under-the-Snow (a grazing centre of three or four huts) to divide the loot, all the equipment the Russians have left behind. Kim winds up with all their papers, their surveying instruments are pitched down a 2000-foot drop because the locals do not know their value and do not want evidence around, and the rest is divided among the coolies.

Meanwhile though at that moment the Bengali suffered acutely in the flesh, his soul was puffed and lofty. A mile down the hill, on the edge of the pine-forest, two half-frozen men—one powerfully sick at intervals—were varying mutual recriminations with the most poignant abuse of the Babu, who seemed distraught with terror. They demanded a plan of action. He explained that they were very lucky to be alive; ... that the Rajah ... would surely cast them into prison if he heard that they had hit a priest. ... Their one hope, said he, was unostentatious flight from village to village till they reached civilization.

Kim has an interesting interaction with the Woman of Shamlegh. She rules the place and all of her husbands (Tibetan women at the time were often polyandrous) are currently off in the hills. She had an English lover in her youth who became ill, left India, and did not return; Kim reminds her of that fellow, though she does not realise why. Through her, Kim is able to send a message through the hills: Tell the villages to feed the Sahibs and pass them on, in peace. We must get them quietly away from our valleys. To steal is one thing—to kill another. The Babu will understand, and there will be no after-complaints.

Back to the plains

The lama, injured and ashamed of the anger he has shown, decides they should head back to the plains. Kim attempts to dissuade him, since he is in no shape for travel, but the old man insists. Eventually, the Woman solves the problem, providing a litter and bearers. That gets them to the plains where they return to the home of the Kulu woman.

Meanwhile Up the valleys of Bushahr ... hurries a Bengali, once fat and well-looking, now lean and weather-worn. He has received the thanks of two foreigners of distinction ... It was not his fault that, blanketed by wet mists, he conveyed them past the telegraph-station and European colony of Kotgarh. It was not his fault ... that he led them into the borders of Nahan, where the Rahah of that State mistook them for deserting British soldiery. ... He begged food, arranged accommodation, proved a skilful leech ...

Bushahr (the area around Rampur), Kotgarh (near Thanedar and famous for orchards) and Nahan are all in Himachal Pradesh.

The reason of his friendliness did him credit. With millions of fellow-serfs, he had learned to look upon Russia as the great deliverer from the North. He was a fearful man. He had been afraid that he could not save his illustrious employers from the anger of an excited peasantry. He himself would just as lief hit a holy man as not, but ... He asked neither pension nor retaining fee, but, if they deemed him worthy, would they write him a testimonial? It might be useful to him later, if others, their friends, came over the Passes. ... They gave him a certificate praising his courtesy, helpfulness, and unerring skill as a guide. He put it in his waist-belt and sobbed with emotion.

Having delivered the Russians to Simla, Hurree returns to Shamlegh-under-the-Snow seeking word of Kim and the lama. Informed that they have gone back to the plains, The Babu groans heavily, girds up his huge loins, and is off again. He does not care to travel after dusk; but his days' marches—there is none to enter them in a book—would astonish folk who mock at his race.

To complete the journey as in the book, you need to return to Saharunpore once more. Backtrack to Shimla first. From there you have two options; backtracking via Dehradun as above, or going to Ambala (dozens of buses every day, 4:20 travel time, alternatively by scenic world heritage-listed mountain train to Kalka and a normal train to Ambala) and Saharunpore is 1.5–2 hours by train from there.

On reaching the Kulu woman's home 📍, an exhausted Kim barely has time to lock up the precious papers before he falls into a fever and requires nursing. She brewed drinks ... She stood over Kim till they went down, and inquired exhaustively after they had come up. ... Best of all, when the body was cleared, she [found] a cousin's widow, skilled in what Europeans, who know nothing about it, call massage. And the two of them ... took him to pieces all one long afternoon—bone by bone, muscle by muscle, ligament by ligament, and lastly, nerve by nerve. Kneaded to irresponsible pulp ... Kim slid ten thousand miles into slumber—thirty-six hours of it—sleep that soaked like rain after drought.

While Kim was indisposed, Hurree Babu has arrived and seen the lama: By Jove, O'Hara, do you know, he is afflicted with infirmity of fits. Yess, I tell you. Cataleptic, too, if not also epileptic. I found him in such a state under a tree in articulo mortem, and he jumped up and walked into a brook and he was nearly drowned but for me. I pulled him out. ... he might have died, but he is dry now, and asserts he has undergone transfiguration.

While Kim was indisposed, Hurree Babu has arrived and seen the lama: By Jove, O'Hara, do you know, he is afflicted with infirmity of fits. Yess, I tell you. Cataleptic, too, if not also epileptic. I found him in such a state under a tree in articulo mortem, and he jumped up and walked into a brook and he was nearly drowned but for me. I pulled him out. ... he might have died, but he is dry now, and asserts he has undergone transfiguration.

Hurree has also summoned Mahbub Ali and asked him to burgle the house and find the hidden papers, but Mahbub was angry ... and would not condescend to such ungentlemanly things. Kim gives Hurree the papers and is told, The old lady thinks I am permanent fixture here, but I shall go away with these straight off—immediately. Mr Lurgan will be proud man. You are offeecially subordinate to me, but I shall embody your name in my verbal report. It is a pity we are not allowed written reports. We Bengalis excel in thee exact science.

When Kim asks about the lama, the Sahiba answers: Thy Holy One is well ... [but] Knew I a charm to make him wise, I'd sell my jewels and buy it. To refuse good food that I cooked myself—and go roving into the fields for two nights on an empty belly—and to tumble into a brook at the end of it—call you that holiness? Then ... he tells me that he has acquired merit. Oh, how like are all men! No, that was not it—he tells me that he is freed from all sin.

Kipling gives us another comic interlude as the lama tries to enlighten Mahbub Ali, who resists the infidel teachings manfully but clearly admires the lama as well. Just as Mahbub departs, Kim arrives and the book ends with the lama informing him So thus the Search is ended. For the merit that I have acquired, the River of the Arrow is here. It broke forth at our feet, as I have said. I have found it. ...

He crossed his hands on his lap and smiled, as a man may who has won salvation for himself and his beloved.