Talk

Talk

The world has over 5,000 different languages, including more than twenty with 50 million or more speakers. Travel can bring you into contact with any of these.

This article tries to give an overview of how to cope with language difficulties, an important problem for many travellers. See our List of phrasebooks for information on specific languages.

Coping without knowing the local language

- Join a tour in your language. This can mean anything from picking up a spoken word tour in the foyer of the museum, to taking an escorted bus tour of an entire country or region. See also guided tours and travel agencies.

- Find venues frequented by English-speakers. Venues such as stand-up comedy clubs are likely to have an English-speaking crowd.

- Hire a guide or translator. This is usually possible, though not always cheap or convenient. If getting things done is more important than saving money — for example, on a business trip — this is often the best solution. Especially if large amounts are involved, it may be safer to use your own translator — for example, one recruited from among immigrants in your country or recommended by your embassy at the destination — than to trust a translator provided by the people you will be negotiating with.

- An electronic translator, like many apps that can be downloaded on a mobile phone, can be extremely useful when making simple requests at hotels, transportation, or even making special requests at restaurants. Count on it being one way communication, but it can often get the message across when hand signs fail.

- A phrasebook or suitable dictionary. Learning the basics of pronunciation, greetings, how to ask directions, and numbers (for transactions) can be enough to fulfil nearly all the essentials of travel on your own, and can be a fun activity on long flights or bus delays.

- Write down numbers or key them into a calculator or phone for display to the other party. Written words are often easier to understand than spoken words, also. This is especially true of addresses, which are often difficult to pronounce intelligibly.

- Try any other languages you speak. Many people in post-Soviet countries speak Russian, some Turks and Arabs speak good French or German, and so on. When one or both players has limited skills in whatever language you are using, keep it simple! Keep sentences short. Use the present tense. Avoid idioms. Use single words and hand gestures to convey meaning.

If none of those work for your situation, you can just smile a lot and use gestures. It is amazing how far this can take you; many people are extremely tolerant. Yet, before switching to body language, it's always a good idea to check the "Respect" sections of the articles for the areas you are going to visit; a well-understood and perfectly innocent gesture in your culture might be a grave insult in another.

Using English

If you can't get your message across in the local language, then as an English speaker you are fortunate that many people around the world learn English as a second language. There are many places where quite a few people speak some English and many in the educated classes speak it well.

There are two groups of countries where good English is common enough that a traveller can generally get by speaking only English:

- Some European countries — especially the Netherlands and the Nordic countries — have widespread exposure to English-language media, strong traditions of learning foreign languages, and good education systems, so many people learn English well. In many European countries that were east of the Iron Curtain, English is widely spoken by the younger generation that grew up after the fall of communism, although not by middle-aged people or the elderly.

- In former colonies of English-speaking powers — all of the Indian Subcontinent, Malaysia, Brunei, Hong Kong, the Philippines, the small Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Israel, most of the Caribbean, most of Oceania, much of eastern and southern Africa and a few other places — English is still widely used, particularly among more affluent sectors of the population.

English has also emerged as the international language in science, with over 90% of modern scientific journal articles being published in English, so academics working in scientific fields in reputable universities around the world generally have a functional command of English.

However, how much effort locals will expend in trying to understand and communicate with you is another matter, and varies between individuals and cultures. To some it comes as a complete surprise that a foreigner would attempt to learn any of their language. To others, it is offensive to start a conversation without at first a courtesy in the local language and a local language request to speak English. There is often no correspondence between ability and willingness to speak a language, many people are lacking in confidence, or don't have the time.

As always, be aware of local norms. You'll get a stern look in Frankfurt if you waste a shopkeeper's time trying out your elementary school German, and the interaction will quickly switch to English. However, in Paris, an initial fumbled attempt in French may make your conversational companion much more comfortable. In a Tokyo restaurant, you may get all of their student waiters gathered around your table to try out their English, while they giggle at any attempt you make in Japanese. Obviously, in general, you shouldn't have the expectation that everyone you meet in your travels will speak English.

Nearly anywhere, if you stay in heavily touristed areas and pay for a good hotel, enough of the staff will speak English to make your trip painless.

The map below shows the percentage of English-speakers overall by nation. Keep in mind, however, that this can be quite misleading as English speaking ability can vary dramatically within countries. In nations where English is not the primary language, English-speakers are more likely to be found in major cities and near major tourist attractions. In Japan, for example, there is a higher concentration of English-speakers in Tokyo and Osaka, but the percentage drops significantly when you travel to rural parts of Shikoku or Kyushu.

South Africa, India and Malaysia can be considered English-speaking countries in terms of areas a tourist would normally visit, and for business meetings, but the national percentage reflects the lower education levels in rural towns and communities. Conversely, in Canada, despite being a majority English-speaking country, there are parts of the country where French is the main language and it might be hard to find people with a functional command of English.

Speaking English with non-native speakers

Imagine, if you will, a Mancunian, Boston, Jamaica and Sydney sitting around a table having dinner at a restaurant in Toronto. They're regaling each other with stories from their hometowns, told in their distinct accents and local argot. But nevertheless, their server can understand all of them, despite being an immigrant from Johannesburg, and so can any other staff at the restaurant if they need to help them. It is a testament to the English language that despite the many differences in these speakers' native varieties, none of these five need to do more than occasionally ask for something said to be repeated.

It may be easy for native English speakers travelling outside the "Anglosphere" today to think they will be understood in everything they say, everywhere. By day you go to tourist sites, perhaps led around by an English-speaking guide, as local merchants hawk souvenirs at you in the same language as the pop songs booming from the nearby radio; pop songs that were a hit at home last year. By evening, back in the hotel, you watch the BBC or CNN news in your room and then perhaps go out to a nearby bar where, along with equally rapt locals, you take in the night's hottest Premier League match on a big-screen TV.

But the ubiquity of English should not blind — or rather, deafen — us to the reality that many of the English speakers we encounter in foreign countries are only as proficient as they need to be to do their jobs. The gentlemanly guide who artfully and knowledgeably discourses on the history and culture of, say, Angkor Wat to you during your walking tour, and shares further insights about life and work over drinks, might well be completely lost if he had to get through one of your days back home. If you want to get an idea of how your conversations with your travelling companions probably sound to him, watch this video (assuming the experience of having the five years of top grades you got in French leave you no closer to understanding that urgent-sounding announcement that just came over the Paris Metro's public-address system wasn't enough, that is). So we have to meet them halfway with our own use of English.

If our foursome were to be eating at a restaurant in Berlin or Dubai, we should first counsel them not on what to do, but what not to do: repeat what they just said more loudly and slowly, or "translate by volume" as it is jokingly called. It helps only if you're normally fairly soft-spoken or in other situations where it's possible your listener genuinely might not have been able to hear you adequately. But it's ridiculous to assume that your English will suddenly become comprehensible if you just raise your voice. And, since it's often the way we speak to children if they don't seem to understand, your listener may well feel as insulted as you would being spoken to loudly and slowly in Hindi, Tagalog or Hungarian.

What the men around the table need to do, like all native English speakers trying to make themselves understood by a non-native speaker with possibly limited English, is, first and foremost, keep in mind that there are aspects of speaking and understanding English which most native speakers have so mastered as children that they forget even exist, but which often present problems for non-native speakers, even those who may have studied English as a foreign language extensively.

Specifically:

- Speak slowly, as you might with even a native speaker who can't understand you. Unlike raising your voice, this isn't such a bad idea. But when you do, remember to preserve your stresses, accenting the same syllables and words you do when speaking at your normal rate. Many non-native speakers rely on these stresses to help them distinguish words and meanings from each other, and when you speak without them, like ... a ... ro ... bot, they may be even more confused than they were before.

- Standardize your English. This means firstly that you avoid idiomatic phrases and just use the plainest, least ambiguous possible words for what you are trying to say. A possibly apocryphal story has it that a veteran Russian translator at the United Nations, stumped by an American diplomat's use of "out of sight, out of mind" in a speech, rendered it into his own native tongue as "blind and therefore insane." Keep that in mind if, for instance, you catch yourself about to tell a sales clerk that you want "the whole nine yards".

- Be mindful of the non-standard aspects of your own pronunciation and vocabulary. You may use impenetrable slang without even realizing it, leaving your listener lost. And consider also what it must have been like to be the server at the five-star Parisian hotel who heard a guest from the Southeastern U.S. give his breakfast order as "Ah'm'om' git me some'm eggs", as if he were in a Georgia diner. While you might be defensive, or even proud, of your thick Glasgow accent, it may be your worst enemy when giving a Bangalore taxi driver the address of the restaurant where you made dinner reservations.

- The English you know may not be the English your listener knows. Bill Bryson, an American writer who lives in England, once said that it sometimes must seem to the rest of the world as if the two nations are being purposely difficult with their divergent vocabularies: for example, in Britain the Royal Mail delivers the post, while in the U.S. the Postal Service delivers the mail. This can also cause problems for native English speakers when abroad, depending on where you are. A valet parking your car at a hotel in Continental Europe may not understand what you mean when you tell him to put a piece of luggage in the trunk, but if you use the British "boot" he will. Similarly, the manager of a Brazilian supermarket might respond to a request for torch batteries with a bemused smile – why would wooden sticks need them?? – but if you tell her it's for a flashlight she'll be able to help you. As a general rule, British English is the main variety taught in the Commonwealth and much of Europe (though increasingly infrequently), while American English is the main variety of English taught in most other countries, though everywhere the omnipresence of American cultural products may mean Americanisms stick rather than any formal English class your conversation partner might have had. See English language varieties for more detailed discussion.

- Avoid phrasal verbs, those in which a common verb is combined with a preposition or two in order to create another verb which may not always be similar in meaning to the original verb, i.e., "to let in" or "to put up with". Because they use such otherwise common words, they seem universally understandable and most native English speakers use them in conversation without thinking twice. But they are the bane of most non-native speakers' existence, since there is often no equivalent in their own native languages and they often have idiomatic meanings that don't relate to any of the words used. Think about it—if you ask someone to put out their cigarette, it would be an entirely understandable response if they took the two words literally and just went to continue smoking outside, or thought you wanted them to do so. You might be better off asking them to extinguish it, especially if they speak a Romance language, since that word has a Latin root they may more easily recognize.

- Avoid negative questions. In English, it's common to answer a question like "They're not going to shoot those horses, are they?" with "No" to confirm that the horses are not going to be shot. However, a listener trying to interpret that question by taking every word literally may say "Yes" to indicate that the person asking was correct in assuming that the horses were not going to be shot... but then the questioner would take that answer as indicating that the horses were going to be shot. Since even native speakers are occasionally confounded by this, and English lacks equivalents to the words some other languages have to indicate this distinction, just ask directly: "Are they going to shoot those horses?" – and give enough context in your own answers.

- Listen actively by keeping your attention on the speaker and verbally affirming, by saying things like "Yes", "OK" and "I am listening" while they are talking to you. When you are talking, continue keeping your eyes on them—if it looks like they're not understanding you, they aren't. Ask them regularly if they are understanding, and echo back what they've told you, or you think they've told you, in some way — "So the next train to Barcelona is at 15:30?" — so they understand what you understand, and have the opportunity to correct you if you don't.

- Suggest continuing the conversation over a drink, if it's culturally appropriate (e.g., not when speaking with a devout Muslim or Mormon). Some studies have shown that people are more relaxed about speaking a second language when they're drinking. It's worth a try if nothing else seems to be working. However, don't overdo it. One beer or two loosen the tongue. Getting totally wasted may well slur your speech so much that you aren't even coherent or comprehensible in your own language, to say nothing of the other dangers of being hammered in an unknown place where nobody speaks your language.

English dialects

Main article: English language varieties

There are variations that a traveller may need to take account of. An American puts things in the trunk of the car and may need to be cautious about speed bumps while a Briton puts them in the boot and drives slowly over sleeping policemen. A job ad in India may want to hire a fresher (new university graduate) at a salary of 8 lakh (800,000 rupees). A Filipino restaurant has a comfort room or CR for each gender. And so on; almost any dialect has a few things that will sound odd to other English speakers. Native speakers of English will usually be able to figure out what most of these mean from context, though it may be more difficult for foreign language learners of English. The others are generally covered in country articles and we have an overview of the major ones at English language varieties.

Even a native English speaker can sometimes have difficulties with the local accent in other English-speaking countries. For example, a Manhattan bartender tells the story of the day a British couple walked in and said what he thought were the words "To Mount Sinai?" He obligingly told them how to get to the nearby hospital of that name, and was surprised and confused when they repeated the request more firmly. Eventually he figured out that they were asking for "two martinis" and mixed them.

And, of course, as noted above, difficulties are more likely for someone who speaks English as a second language. There are some well-known differences between American and British English, but you will find many more local differences in spelling, and even similar words used for completely different concepts as you travel through countries.

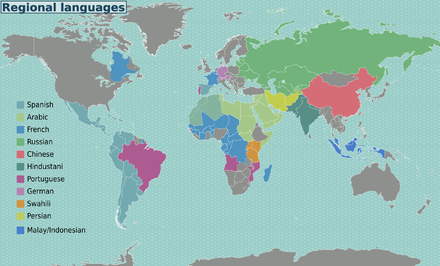

Regional languages

In many areas, it is very useful to learn some of a regional language. This is much easier than trying to learn several local languages, and is generally more useful than any one local language.

Regional languages that are widely used across large areas encompassing many countries are:

- Spanish for Spain, most of Latin America and Equatorial Guinea.

- Arabic for the Middle East, North Africa, Mauritania, Sudan, South Sudan, Chad, Somalia, Djibouti and the Comoros.

- Russian for Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, the Baltic States, Central Asia, Mongolia, and the Caucasus.

- French for France, Belgium, Monaco, Luxembourg, Switzerland, the Aosta Valley (Italy), and former colonies: Quebec, French Guiana, most of West Africa, western North Africa, Haiti, and a fair number of island nations in Africa, the Lesser Antilles, and Oceania.

Other useful regional languages include:

- Chinese, also referred to as Mandarin or Putong hua (common speech), as the lingua franca for multilingual China, as well as Taiwan, Singapore and the ethnic Chinese community of Malaysia. It has more native speakers than any other language, more than double the numbers for 2nd-place Spanish or 3rd-place English.

- German for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein (also useful throughout Central Europe and in Turkey). There is a German-speaking minority in Namibia, but more people there speak English.

- So-called Hindustani, a language comprised of mutually intelligible Hindi and Urdu (or one of these separate languages), for India and Pakistan, as well as the ethnic Indian community in Fiji.

- Italian naturally for Italy, but also San Marino, the Vatican City and Switzerland, as well as significant minorities in Malta, Slovenia and the French island of Corsica.

- Malay/Indonesian is useful, naturally, for Malaysia and Indonesia, but also for neighbouring Brunei, Singapore, and East Timor, and some parts of Southern Thailand and the southern Philippines.

- Persian for Iran, Afghanistan, and to a lesser degree Tajikistan.

- Portuguese for a motley assortment of Portugal, Brazil, East Timor, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau and São Tomé and Príncipe.

- Swahili for Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and to a lesser degree the other countries of East Africa.

Even in really out-of-the-way places, you should at least be able to find hotel staff and guides who speak the regional language well. English is unlikely to be much use in a small town in Uzbekistan, for example, but Russian is quite widely spoken.

Regional languages are often useful somewhat beyond the borders of their region. Some Russian is spoken in Northern China and in Israel, some German in Turkey and Russia, and so on. In Uzbekistan, Persian could be worth a try. Portuguese and Spanish are not exactly mutually intelligible per se (especially if you speak Spanish and try to decipher spoken Portuguese), but if you and your conversation partner speak slowly and adapt the speech patterns to the other language, you will probably be able to get the most important points across the language barrier. People in the border regions between Uruguay and Brazil do this quite often. Written Romance languages are often possible to decipher if you know some Latin or any given Romance language and have at least heard of some linguistic shifts (e.g. Latin t and p becoming Spanish b and d, Latin ct becoming Spanish ch and Italian tt), so you may be able to get that estación is probably the same as stazione and other similar stuff. Of course "false friends" are common, so don't overly rely on this method.

Widely used expressions

Tea

The word for tea in many of the world's languages originally came from Chinese, either te (from Minnan in Fujian) or cha (from Cantonese in Guangdong/Canton). Across much of Asia, it sounds like "cha" (Mandarin and Cantonese, albeit with different tones, and many East Asian languages like Japanese, Korean, etc.) or "chai" (Hindi, Russian, Persian, much of the Balkans, etc.). In many Western European languages and Malay/Indonesian, it sounds like "te", "teh", or "tee".

Exceptions are pretty rare. The Burmese word for tea is lahpet, which may derive from the same ancient ancestor as the Chinese words. Polish, Belarusian, and Lithuanian use variants of herbata, which come from Dutch herba thee or Latin herba thea ("tea herb") and are cognate with English "herb".

A few English words may be understood anywhere, though which ones will vary from place to place. For example, simple expressions like "OK", "bye-bye", "hello" and "thank you" are widely used and understood by many Chinese. Unless you are dealing with academics or people working in the tourism industry, however, that may well be the extent of their English.

French words also turn up in other languages. "Merci" is one way to say "thank you" in languages as disparate as Persian, Bulgarian, Turkish and Catalan.

English idioms may also be borrowed. "Ta-ta" is common in India, for example.

Abbreviations like CD and DVD are often the same in other languages. "WC" (water closet) for toilet seems to be widely used, both in speech and on signs, in various countries, though not in most English-speaking ones.

Words from the tourist trade, such as "hotel", "taxi", and "menu", may be understood by people in that line of work, even if they speak no other English.

Some words have related forms across the Muslim world. Even if you use the form from another language, you might still be understood.

- "Thank you" is shukran in Arabic, teshekkür in Turkish, tashekor in Dari (Afghan Persian), shukria in Urdu.

- In'shallah has almost exactly the same meaning as English "God willing". Originally Arabic, it is now used in most Islamic cultures. A variant even found its way into Spanish - ojalá (meaning hopefully)

- The word for peace, used as a greeting, is shalom in Hebrew and salaam in Arabic. The related Malay/Indonesian word selamat, which means "safe," is also used in greetings. (However, salamat is closer to "thank you" in many Philippine languages).

Some loanwords may be very similar in a number of languages. For example, "sauna" (originally from Finnish) sounds similar in Chinese and English among other languages. Naan is Persian for bread; it is used in several Indian languages and in the Uyghur language. Baksheesh might translate as gift, tip or bribe depending on context; it is a common expression in various languages anywhere from Turkey to Sri Lanka.

Sanskrit has also strongly influenced many South Asian and Southeast Asian languages, and numerous Sanskrit loan words can be found in those languages. As an example "bhā́ṣā", the Sanskrit word for "language" becomes "bhāṣā" in Hindi, "pācai" in Tamil, "bahasa" in Malay and Indonesian, "paa-sǎa" in Thai, "phiəsaa" in Khmer and so on. "Roti" is used in many languages to refer to flatbreads, or in some languages even bread in general.

Language learning

There are many ways to learn a language. Universities or private schools in many places teach most major world languages. If the language is important for business, then there will usually be courses available at the destination; for example in major Chinese cities both some of the universities and many private schools offer Mandarin courses for foreigners.

For travellers, it is common to learn a language from a "sleeping dictionary" (a local lover) or to just pick it up as you go along, but often more formal instruction is available as well. In countries where many languages are spoken but there is an official national language — such as Mandarin, Filipino or Hindi — most school teachers have experience teaching the official language, and often some of them would welcome some extra income.

There are also many online resources. Wikivoyage has phrasebooks for many languages. An Open Culture site has free lessons for 48 languages.

Variants, dialects, colloquialisms and accents

Variance, dialects and accents add diversity and colour to travel. Similar to English, other languages can also have dialectal differences between different parts of the world. For instance, there are some differences in standard Mandarin between mainland China and Taiwan, and while they are largely mutually intelligible, misunderstandings can arise from these differences (e.g. 小姐 xiǎojiě is the equivalent of the title "Miss" in Taiwan, but means "prostitute" in mainland China). Similarly, there are such differences between Brazilian and European Portuguese (e.g. bicha is a line of people waiting in Portugal, but a very derogatory way of referring to a gay man in Brazil), as well as between Latin American and European Spanish (e.g. coger is the verb "to take (a bus, train, etc.) in Spain, but means "to fornicate" in Latin America).

Language as a reason for travel

It is fairly common for language to be part of the reason for various travel choices.

- Some travellers choose destinations based partly on the language. For example, an English speaker might choose to visit Malaysia rather than Thailand, or Jamaica rather than Mexico because it is easier to cope with a country where English is widely spoken. Similarly, one of Costa Rica's main draws compared to its northern neighbors is the much higher English proficiency among second language speakers, even if few native speakers live in either country.

- Others may choose a destination where a language they want to learn or improve is spoken; see Language tourism.

- Still others may use language teaching as a method of funding their travel; see Teaching English. Language is almost never the only reason for these choices, but it is sometimes a major factor.

Respect

In some areas, your choice of language can have political connotations. In some former Soviet republics and other former Eastern Bloc countries, Russian may be a symbol of Soviet oppression, and many locals may well feel offended if you speak Russian to them as if that were their language. Several other languages may similarly be associated with occupation, oppression or hostile relations (e.g. Mandarin in Hong Kong). Often there are still large minorities with those languages as their mother tongue, and individuals may have other ties to them, so don't mock those languages either.

Often the offensive language is one most locals have studied, and one that you studied because it is widespread in a region you are interested in. In such cases it may help to start the conversation with the few words you know in the local language, hint on your knowing that other one and hope the local will switch.

See also

Related: List of phrasebooks